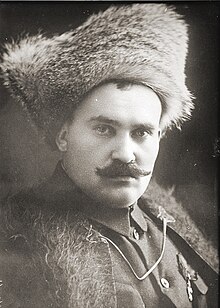

Grigory Mikhaylovich Semyonov

Grigory Mikhaylovich Semyonov | |

|---|---|

Ataman Semyonov | |

| Born | September 25, 1890 Kuranzha Village, Transbaikal Oblast, Russian Empire |

| Died | August 30, 1946 (aged 55) Moscow, Russian SFSR, USSR |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1911–21 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Battles/wars | World War I Russian Civil War |

| Awards | Order of St. George (twice[clarification needed]) |

Grigory Mikhaylovich Semyonov, or Semenov (Russian: Григо́рий Миха́йлович Семёнов; September 13 (25), 1890 – August 30, 1946), was a Japanese-supported leader of the White movement in Transbaikal and beyond from December 1917 to November 1920, a lieutenant general, and the ataman of Baikal Cossacks (1919).[1]

Early life and career[]

Semyonov, born in the Transbaikal region of eastern Siberia, had partial Buryat ancestry through his father, Mikhail Petrovich Semyonov. Semyonov spoke Mongolian and the Buryat fluently. He joined the Imperial Russian Army in 1908 and graduated from Orenburg Military School in 1911. Commissioned first as a khorunzhiy (cornet or lieutenant), he rose to the rank of yesaul (Cossack captain), distinguished himself in battle against the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians in World War I, and earned the Saint George's Cross for courage.[2]

Pyotr Wrangel wrote[3]

Semenov was a Transbaikalian Cossack – dark and thickset, and of the rather alert Mongolian type. His intelligence was of a specifically Cossack calibre, and he was an exemplary soldier, especially courageous when under the eye of his superior. He knew how to make himself popular with Cossacks and officers alike, but he had his weaknesses in a love of intrigue and indifference to the means by which he achieved his ends. Though capable and ingenious, he had received no education, and his outlook was narrow. I have never been able to understand how he came to play a leading role.

As somewhat of an outsider among his fellow officers because of his ethnicity, he met another officer shunned by his peers, Baron Ungern-Sternberg, whose eccentric nature and disregard of the rules of etiquette and decorum repelled others. He and Ungern tried to organize a regiment of Assyrian Christians to aid in the Russian fight against the Ottomans. In July 1917, Semyonov left the Caucasus and was appointed commissar of the Provisional Government in the Baikal region and was responsible for recruiting a regiment of Buryat volunteers.[4]

Russian Civil War in Transbaikal[]

After the October Revolution, Semyonov stirred up a sizable anti-Soviet rebellion but was defeated after several months of fighting, and he fled to the northeastern Chinese city of Harbin.[5] In August 1918, he managed to consolidate his positions in the Transbaikal region with the help of the Czechoslovak Legions and imposed his ruthless regime. In his rule over the region, he has been described as a "plain bandit [who] drew his income from holding up trains and forcing payments, no matter what the nature of the load nor for whose benefit it was being shipped."[6] Semyonov declared a "Great Mongol State" in 1918 and had designs to unify the Oirat Mongol lands, portions of Xinjiang, Transbaikal, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Tannu Uriankhai, Kobdo, Hulunbei'er, and Tibet into one Mongolian state.[7] The White Siberian Provisional Government appointed Semyonov commander of a detached unit with headquarters in Chita. Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak initially refused to recognize Semyonov's authority but was eventually forced to accept Semyonov as the de facto leader and to confirm him as commander-in-chief of the Chita military district.

In early 1919, Semyonov declared himself ataman of the Transbaikal Cossack Host with support from the Imperial Japanese Army, some of whose elements had been deployed to Siberia. The region under his control, also called Eastern Okraina, extended from Verkhne-Udinsk near Lake Baikal to the Shilka River and the town of Stretensk, to Manzhouli, where the Chinese Eastern Railway met the Chita Railway and northeast some distance along the Amur Railway.[8]

Semyonov handed out copies of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to the Japanese troops with whom he became associated.[9]

After the fall of Kolchak's Siberian government, he transferred power to Semyonov in the Far East. However, Semyonov was unable to keep his forces in Siberia under control: they stole, burned, murdered, and raped and so they developed a reputation for being little better than thugs.[10] In July 1920, the Japanese Expeditionary Corps started a limited withdrawal in accordance with the Gongota Agreement, which was signed with the Far Eastern Republic and undermined support for Semyonov. Transbaikal partisans, internationalists, and the 5th Soviet Army under Genrich Eiche launched an operation to retake Chita. In October 1920, units of the Red Army and guerrillas forced Semyonov's army out of the Baikal region. After having retreated to Primorye, Semyonov tried to continue fighting the Soviets but was finally forced to abandon all of Russian territory by September 1921.[11]

In exile[]

After failing to settle in Nagasaki via Harbin, Semyonov stayed in the United States but was soon accused of committing acts of violence there against the American soldiers of the Expeditionary Corps.[citation needed] He was eventually acquitted and returned to China, where he was given a monthly 1000-yen pension by the Japanese government. In Tianjin, he made ties with the Japanese intelligence community and mobilized exiled Russian and Cossack communities that planned an eventual overthrowing the Soviets. He was also employed by Puyi, the dethroned Emperor of China, whom he wished to restore to power.[12][13]

Semyonov was captured in Dalian by Soviet paratroopers in September 1945 during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in which the Red Army conquered Manchukuo. He was charged with counterrevolutionary activities, sentenced to death by hanging by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, and was executed on August 29, 1946.[14]

References[]

- ^ Bisher, Jamie, White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian, Routledge, London, 2009.

- ^ Bisher, White Terror.

- ^ Always With Honour. By General baron Peter N Wrangel. Robert Speller & Sons. New York. 1957.

- ^ Bisher, White Terror.

- ^ Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. p. 152.

- ^ Norton, Henry Kittredge (1923). "The Far Eastern Republic of Siberia." London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. p69.

- ^ Paine 1996, pp. 316-7.

- ^ Bisher, White Terror.

- ^ Tokayer, Marvin (1979). The Fugu Plan. New York: Paddington Press Ltd. p47.

- ^ Richard Pipes, Russia under the Bolshevik Regime, New York 1994, p.46, and Bisher, White Terror.

- ^ Bisher, White Terror.

- ^ Arnold C. Brackman, The Last Emperor. Hew York: Scribner's, 1975, p. 151.

- ^ Williams, Stephanie (2011). Olga's Story: Three Continents, Two World Wars, and Revolution -- One Woman's Epic Journey Through the Twentieth Century. Doubleday Canada. p. 327.

- ^ Bisher, White Terror.

- Paine, S. C. M. (1996). Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563247240. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

External links[]

- White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian – Website for the book White Terror.

- 1890 births

- 1946 deaths

- People from Ononsky District

- People from Transbaikal Oblast

- White movement generals

- Russian generals

- Russian anti-communists

- Russian people of World War I

- People of the Russian Civil War

- Warlords

- White Russian emigrants to China

- White Russian emigrants to Japan

- Russian people of Buryat descent

- People of Manchukuo

- History of Zabaykalsky Krai

- Primorsky Krai

- Russian people executed by the Soviet Union

- Executed Russian people

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Japan

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to China

- People executed by the Soviet Union by hanging

- Russian collaborators with Imperial Japan