Hallucigeniidae

| Hallucigeniidae | |

|---|---|

| |

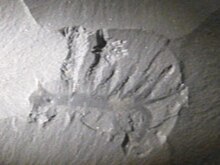

| The type specimen Hallucigenia sparsa from the Burgess Shale | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| (unranked): | Panarthropoda |

| Phylum: | †"Lobopodia" |

| Clade: | †Hallucishaniids |

| Family: | †Hallucigeniidae Conway Morris, 1977 |

| Genera | |

| |

Hallucigeniidae is a family of extinct worms belonging to the group Lobopodia that originated during the Cambrian explosion. It is based on the species Hallucigenia sparsa, the fossil of which was discovered by Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1911 from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia. The name Hallucigenia was created by Simon Conway Morris in 1977, from which the family was erected after discoveries of other hallucigeniid worms from other parts of the world.[1] Classification of these lobopods and their retatives are still controversial, and the family consists of at least four genera.

History of discovery[]

The first fossil of hallucigeniid worm was discovered by an American palaeontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott from the Walcott Quarry that contains the Cambrian Burgess Shale. In 1911, Walcott gave the name Canadia sparsa as he believed that it was related to the polychaete worm (Annelida) Canadia spinosa, which he described simultaneously.[2] British palaeontologist Simon Conway Morris re-examined the specimen and concluded that it was not a Canadia species. He created a new genus Hallucigenia in 1977.[3][4] With only a single species and fragmentary fossils available, the relationship of the worm with other animals was not obvious. The most prominent feature of the worm, its body projections were particularly difficult to understand as there were two distinct groups, the tube-like tentacles and thorn-like spines. Morris described the spines as the legs and the tentacles as feeding apparatus.[5] Two other species were later discovered from the Cambrian Maotianshan shales of China, H. fortis in 1995,[6] and H. hongmeia in 2012.[7]

In 1991, Lars Ramsköld (Uppsala University, Sweden) and Hou Xian-Guang (Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) described a new specimen, Microdictyon, from the lower Cambrian Maotianshan shales. With this relatively complete fossil, they assigned the animal to and reinterpreted Hallucigenia as a lobopodian, a legged worm-like taxon which were still thought to be exclusively related to onychophoran (velvet worm) at that time.[8][9] They were also able to work out that by inverting the specimen upside down, the so-called tentacles were actually walking legs (called lobopods) and the spines were protective armours on the back.[5][10] The reinterpretation was strengthened by the discovery of new species Cardiodictyon catenulum from the same Maotianshan shales, reported by Hou, Ramsköld and Jan Bergström in the same year.[11]

In 2012, a different lobopodian fossil was discovered from the Permian (about 296 million years old) sediments of the Mazon Creek in Illinois, US. Joachim T. Haug, Georg Mayer, Carolin Haug, Derek E.G. Briggs gave the name Carbotubulus waloszeki.[12] In 2018, Thanahita distos was described by Derek J. Siveter, Briggs, David J. Siveter, Mark D. Sutton and David Legg from the Herefordshire Lagerstätte at the England–Wales border in UK.[13] Dated to about 430 million years old, it is the only known extinct lobopodian in Europe and the first Silurian lobopod known worldwide.[14][15]

Description[]

Hallucigeniid worms are elongated, soft-bodied animals characterised by several pairs of stumpy legs known as lobopods, for which they are included in the larger but informal group of animals, Lobopodia. Their body can be described in three parts: the head, neck, and the trunk. The head bears a pair of eyes.[1][16] The neck can be prominent in some species such as T. distos in which it bears two pairs of small legs.[13] The trunk is the longest part of the body and contains several pairs of legs on the frontal (ventral) side and several pairs of spines on the back (dorsal) side. Each legs has terminal claws. C. catenulum, measuring 2.5 cm long, bears about 25 pairs of legs.[17]

T. distos, though incomplete, is the longest with 3 cm body length and bears at least nine pairs of legs.[18] Hallucigenia species are highly diverse in body sizes, H. fortis is only about 1 cm long, H. hongmeia is intermediate with about 3 cm in length, and H. sparsa being the longest measuring 5.5 cm.[7][19]

References[]

- ^ a b Caron, Jean-Bernard; Aria, Cédric (2017). "Cambrian suspension-feeding lobopodians and the early radiation of panarthropods". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (1): 29. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0858-y. PMC 5282736. PMID 28137244.

- ^ Walcott, C. (1911). Cambrian Geology and Paleontology II. Middle Cambrian annelids. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 57(5): 109-145.

- ^ Conway Morris, Simon (1977). "A new metazoan from the Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia" (PDF). Palaeontology. 20 (3): 623–640.

- ^ Brysse, Keynyn (2008). "From weird wonders to stem lineages: the second reclassification of the Burgess Shale fauna". Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 39 (3): 298–313. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2008.06.004. PMID 18761282.

- ^ a b Liu, Jianni; Dunlop, Jason A. (2014). "Cambrian lobopodians: A review of recent progress in our understanding of their morphology and evolution". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 398: 4–15. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.06.008. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Hou, Xiangguang; Bergström, Jan (1995). "Cambrian lobopodians-ancestors of extant onychophorans?". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 114 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1995.tb00110.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b Steiner, Michael (2012). "A new species of Hallucigenia from the Cambrian Stage 4 Wulongqing Formation of Yunnan (South China) and the structure of sclerites in lobopodians" (PDF). Bulletin of Geosciences. 87 (1): 107–124. doi:10.3140/bull.geosci.1280.

- ^ Ramsköld, L.; Hou, X.-G. (1991). "New early Cambrian animal and onychophoran affinities of enigmatic metazoans". Nature. 351 (6323): 225–8. Bibcode:1991Natur.351..225R. doi:10.1038/351225a0. S2CID 4309565.

- ^ Ortega-Hernández, Javier (5 October 2015). "Lobopodians". Current Biology. 25 (19): R873–R875. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.028. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 26439350.

- ^ Ramsköld, Lars (April 1992). "The second leg row of Hallucigenia discovered". Lethaia. 25 (2): 221–4. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1992.tb01389.x.

- ^ Xianguang, Hou; Ramsköld, Lars; Bergström, Jan (1991). "Composition and preservation of the Chengjiang fauna –a Lower Cambrian soft-bodied biota". Zoologica Scripta. 20 (4): 395–411. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.1991.tb00303.x. ISSN 1463-6409.

- ^ Haug, Joachim T.; Mayer, Georg; Haug, Carolin; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2012). "A Carboniferous Non-Onychophoran Lobopodian Reveals Long-Term Survival of a Cambrian Morphotype". Current Biology. 22 (18): 1673–1675. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.066. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ a b Siveter, Derek J.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Siveter, David J.; Sutton, Mark D.; Legg, David (2018). "A three-dimensionally preserved lobopodian from the Herefordshire (Silurian) Lagerstätte, UK". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (8): 172101. doi:10.1098/rsos.172101. PMC 6124121. PMID 30224988.

- ^ "New species of rare ancient 'worm' discovered in fossil hotspot | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. 8 August 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Shelton, Jim (9 August 2018). "Researchers discover Silurian relative of the Cambrian lobopod Hallucigenia". YaleNews. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Ma, Xiaoya; Hou, Xianguang; Aldridge, Richard J.; Siveter, David J.; Siveter, Derek J.; Gabbott, Sarah E.; Purnell, Mark A.; Parker, Andrew R.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (1 September 2012). "Morphology of Cambrian lobopodian eyes from the Chengjiang Lagerstätte and their evolutionary significance". Arthropod Structure & Development. 41 (5): 495–504. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2012.03.002. ISSN 1467-8039. PMID 22484085.

- ^ Ramsköld, L., & Chen, J.-Y. (1998). Cambrian Lobopodians: Morphology and Phylogeny. In Arthropod fossils and phylogeny (pp. 107–150). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231096546

- ^ Buchholz, Pete (2018). "Late-living kin of iconic Burgess Shale worm found in England". Earth Archives. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Smith, M. R.; Ortega-Hernández, J. (2014). "Hallucigenia's onychophoran-like claws and the case for Tactopoda" (PDF). Nature. 514 (7522): 363–366. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..363S. doi:10.1038/nature13576. PMID 25132546. S2CID 205239797.

- Lobopodia

- Maotianshan shales fossils

- Burgess Shale fossils

- Cambrian animals