Helene Schjerfbeck

Helene Schjerfbeck | |

|---|---|

Early 1890s. | |

| Born | Helena Sofia Schjerfbeck July 10, 1862 |

| Died | January 23, 1946 (aged 83) |

| Nationality | Finnish |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Naturalism (arts), Realism and Expressionism |

| Signature | |

| |

Helena Sofia (Helene) Schjerfbeck (pronounced [heˈleːn ˈɕæ̌rvbek] (![]() listen); July 10, 1862 – January 23, 1946) was a Finnish painter. A modernist painter, she is known for her realist works and self-portraits, and also for her landscapes and still lifes. Throughout her long life, her work changed dramatically beginning with French-influenced realism and plein air painting. It gradually evolved towards portraits and still life paintings. At the beginning of her career she often produced historical paintings, such as the Wounded Warrior in the Snow (1880), At the Door of Linköping Jail in 1600 (1882) and The Death of Wilhelm von Schwerin (1886). Historical paintings were usually the realm of male painters, as was the experimentation with modern influences and French radical naturalism. As a result, her works produced mostly in the 1880s did not receive a favourable reception until later in her life.[1]

listen); July 10, 1862 – January 23, 1946) was a Finnish painter. A modernist painter, she is known for her realist works and self-portraits, and also for her landscapes and still lifes. Throughout her long life, her work changed dramatically beginning with French-influenced realism and plein air painting. It gradually evolved towards portraits and still life paintings. At the beginning of her career she often produced historical paintings, such as the Wounded Warrior in the Snow (1880), At the Door of Linköping Jail in 1600 (1882) and The Death of Wilhelm von Schwerin (1886). Historical paintings were usually the realm of male painters, as was the experimentation with modern influences and French radical naturalism. As a result, her works produced mostly in the 1880s did not receive a favourable reception until later in her life.[1]

Her work starts with a dazzlingly skilled, somewhat melancholic version of late-19th-century academic realism…it ends with distilled, nearly abstract images in which pure paint and cryptic description are held in perfect balance. (Roberta Smith, New York Times, November 27th 1992)[2]

Schjerbeck's birthday, 10 July, is Finland's national day for the painted arts.

Early life[]

Helena Sofia Schjerfbeck was born on July 10, 1862, in Helsinki, Finland (then an autonomous Grand-Duchy within the Russian Empire), to Svante Schjerfbeck (an office manager) and Olga Johanna (née Printz).[3] She had one surviving brother, Magnus Schjerfbeck (1860–1933), who went on to become an architect.[1] In 1866, when she was four she fell down some stairs injuring her hip, which prevented her from attending school and left her with a limp for the rest of her life. She showed talent at an early age, and, in 1873, by the time she was eleven she was enrolled at the Finnish Art Society School of Drawing. Her fees were paid by Adolf von Becker, who saw promise in her.[4] At this school Schjerfbeck met Helena Westermarck. These two, and artist Maria Wiik and lesser known Ada Thilen had a close friendship during their lives.[5][1]

When Schjerfbeck's father died of tuberculosis on February 2, 1876, Schjerfbeck's mother took in boarders so that they could get by. A little over a year after her father's death, Schjerfbeck graduated from the Finnish Art Society drawing school. She continued her education, with Westermarck, at a private academy run by Adolf von Becker, which utilised the University of Helsinki drawing studio. Professor paid for her tuition to Becker's private academy. There, Becker himself taught her French oil painting techniques.[1]

In 1879, at the age of 17, Schjerfbeck won third prize in a competition organised by the Finnish Art Society, and in 1880 her work was displayed in an annual Finnish Art Society exhibition. That summer Schjerfbeck spent time at a manor owned by her aunt on her mother's side, Selma Printz, and Selma's husband Thomas Adlercreutz. There she spent time drawing and painting her cousins. Schjerfbeck became particularly close to her cousin Selma Adlercreutz, who was her age. In 1880, she set off to Paris later that year after receiving a travel grant from the Imperial Russian Senate.[1]

Career[]

Paris[]

In Paris, Schjerfbeck painted with Helena Westermarck, then left to study with Léon Bonnat at Mme Trélat de Vigny's studio. In 1881 she moved to the Académie Colarossi, where she studied once again with Westermarck. The Imperial Senate gave her another scholarship, which she used to spend a couple of months in Meudon, and then a few more months in Pont-Aven a small fishing in Concarneau, Brittany. She then went back to the Académie Colarossi briefly, before returning to the in Finland. Schjerfbeck continued to move around frequently, painting and studying with various people. Schjerfbeck made money by continuing to put her paintings in the Art Society's exhibitions, and she also did illustrations for books. After returning to Finland in 1882, in 1884 she was back in Paris at the Académie Colarossi with Westermarck, but this time they were working there. During this time she participated in Académie des Beaux-Arts’ The Salon and painted again in Brittany. In the chapel of Trèmolo near the village of Pont-Aven Schjerfbeck produced the painting The Door (1884).[1]

Engagement and travels[]

In late Autumn 1883, Schjerfbeck got engaged to a Swedish painter Otto Hagborg who also lived in Pont-Aven in the winter and spring of 1883–1884. The engagement, however, came to an end in 1885 when a problem with Schjerfbeck's hip led the groom's family to suspect tuberculosis. In reality the issue was a result of her fall during childhood. Schjerfbeck never married.[1]

After spending a year in Finland, Schjerfbeck travelled again to Paris in the autumn of 1886. Schjerfbeck was given more money to travel by a man from the Finnish Art Society and in 1887 she travelled to St Ives, Cornwall, in Britain.[1] There she painted The Bakery (1887) and The Convalescent, the latter winning the bronze medal at the 1889 Paris World Fair. The painting was later bought by the Finnish Art Society. During this period Schjerfbeck was painting in a naturalistic plein-air style.

Teaching and sanatorium[]

In the 1890s Schjerfbeck started teaching regularly in Finland at the Art Society drawing school, now the Academy of Fine Arts. Hilda Flodin was one of her students.[7] However, in 1901 she became too ill to teach and in 1902 she resigned from her post. She moved to Hyvinkää, which was known for its sanatorium, all while taking care of her mother who lived with her (the mother died in 1923). While living in Hyvinkää, she continued to paint and exhibit.[2] "Schjerfbeck’s sole contact with the art world was through magazines sent by friends."[8] Since she did not have art, Schjerfbeck took up hobbies like reading and embroidery.

During this time Schjerbeck produced still lifes and landscape paintings, as well as portraits, such as that of her mother, local school girls and women workers, and also self-portraits, and she became a modernist painter. Her work has been compared to that of artists such as James McNeill Whistler and Edvard Munch,[2] but from 1905 her paintings took on a character that was hers alone. She continued experimenting with various techniques such as using different types of underpainting.

Exhibitions[]

In 1913 Schjerfbeck met the art-dealer , with whose encouragement she exhibited at Malmö in 1914, Stockholm in 1916 and St Petersburg in 1917. In 1917 Stenman organised her first solo exhibition and in that year (alias H. Ahtela) published the first Schjerfbeck monograph. Later she exhibited at Copenhagen (1919), Gothenburg (1923) and Stockholm (1934). In 1937 Stenman organised another solo exhibition for her in Stockholm,[2] and in 1938 he began paying her a monthly stipend. Her paintings were successfully displayed in several exhibitions in Sweden in the 1930s and 1940s.

Later years and death[]

As the years passed, Schjerfbeck travelled less. When a family matter arose she would return to her home city of Helsinki and she spent most of 1920 in Ekenäs, but by 1921 she was back living in Hyvinkää.

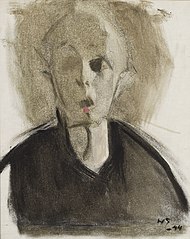

For about a year, Schjerfbeck moved to a farm in Tenala to avoid the Winter War, but went back to Ekenäs in the middle of 1940. She later moved into a nursing home, where she resided for less than a year before moving to the Luontola sanatorium. In 1944 she moved into the Saltsjöbaden spa hotel in Sweden, where she continued to paint actively even during her last years; e.g. the series of self-portraits.[1]

She died on January 23, 1946 and was buried at the Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki.[12]

Self-Portrait, 1939

Self-Portrait, 1942

Self-Portrait With Red Spot, 1944

Grave at Hietaniemi Cemetery

Work[]

Dancing Shoes is one of Schjerfbeck's most popular paintings and she returned to the theme three times as well as executing a lithograph of it, the latter catapulting the painting to international fame. It depicts her cousin Esther Lupander, who had extremely long legs and for that reason the painting was nicknamed "The Grasshopper". Executed in Realist style, the painting shows the clear influence of Schjerfbeck's stay in Paris where she had expressed admiration for Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Mary Cassatt. It fetched £3,044,500 at a 2008 Sotheby's London sale.[13]

Girl with Blonde Hair (1916) is an example of Schjerfbeck's mature style, drawing on French Modernism. The work belongs to a series (including also The Family Heirloom of the same year) featuring neighbours of Schjerfbeck, Jenny and Impi Tamlander, who ran errands for Schjerfbeck and her mother and helped look after the family home. Here the sitter is Impi. The painting realized £869,000 at a 2015 Sotheby's London sale.[14] Schjerfbeck was included in the 2018 exhibit Women in Paris 1850–1900.[15]

Dancing Shoes, 1882.

The Family Heirloom, 1916.

Girl with Blonde Hair, 1916. (fi)

Legacy[]

Art forger was an admirer of hers and writes of his time forging Schjerfbeck's works: "By encroaching on Schjerfbeck I felt like I had violated something sacred. It was if I had broken into a sacristy to steal the church silvers." Fellow forger and self-admitted seller of 60 Schjerfbeck counterfeits Jouni Ranta was more critical and opined her fame was undeserved.[16]

The 2003 biographical novel Helene by Rakel Liehu was a critical and commercial success, and won the 2004 Runeberg Prize.[17] It also formed the basis of a 2020 film by the same name, directed by Antti Jokinen and starring Laura Birn as Schjerfbeck,[18] which was nominated for an award in the feature-length category at the Shanghai International Film Festival.[19]

Exhibitions[]

- From 20 July to 27 October 2019, Royal Academy set up an exhibition with over 60 paintings, landscapes and still lifes, remarking the evolution of her career.[20][21]

See also[]

- Golden Age of Finnish Art

- Art in Finland

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Konttinen, Riina. "Schjerfbeck, Helene (1862–1946)". National Biography of Finland. Translated by Fletcher Roderick. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Roberta (27 November 1992). "Review/Art: A Neglected Finnish Modernist Is Rediscovered". New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ Lindroos, Charlotte; Löyttyniemi, Raili (7 July 2017). "Omakuvista tunnettu Helene Schjerfbeck rikkoi rajoja monella tavalla". Yle. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Ahtola-Moorhouse, Lena: 'Schjerfbeck, Helene [Helena] (Sofia)'

- ^ "Taiteiljatoveruutta. Helene Schjerfbeck, Maria Wiik, Helena Westermarck ja Ada Thilén" (in Finnish). Lukulamppu. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- ^ "Haavoittunut enkeli on suomalaisten suosikkitaulu". Yle. 2 December 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Bonsdorff, Bengt von. "Flodin, Hilda". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Facos, Michelle. 'Helene Schjerfbeck’s Self-Portraits', in Woman’s Art Journal; 16 (Spring 1995): 12-7.

- ^ Halonen, Kaisa (21 March 2012). "Hiljaiset kasvot". Kirkko ja kaupunki. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Kolsi, Eeva-Kaarina (1 December 2018). "Taiteilijanero vei salaisuuden hautaan: Kuka oli Helene Schjerfbeckin salaperäinen kihlattu?". Ilta-Sanomat. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Helene Schjerfbeckin muotokuva Matti Kiianlinnasta Serlachius-museoille". Amusa. 27 November 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Hietaniemen hautausmaa– merkittäviä vainajia" (PDF) (in Finnish). Helsingin seurakuntayhtymä. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ "Dancing Shoes". Sotheby's.

- ^ "Girl with Blonde Hair". Sotheby's.

- ^ Madeline, Laurence (2017). Women artists in Paris, 1850–1900. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22393-4.

- ^ Kotirinta, Pirkko (25 June 2020). "Suomen taitavimpiin kuulunut väärentäjä Veli Seppä kertoo kirjassa, kuinka helppoa työ oli – Kymmeniä väärennettyjä Schjerfbeckejä saattaa yhä seikkailla jossain". Helsingin Sanomat. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Rakel Liehun Valaanluiset koskettimet kertoo runoilijan omakohtaisen kasvukertomuksen – kiehtovasti pianon näkökulmasta" (in Finnish). Helsingin Sanomat. 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Helene (2020)". IMDb. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "Antti J. Jokisen Helene-elokuva on valittu ehdolle kansainvälisen elokuvafestivaalin kilpasarjaan" (in Finnish). Keski-Uusimaa. STT. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "Helene Schjerfbeck's exhibition at Royal Academy of Arts". Royal Academy of Arts.

- ^ "Finland's Munch': the unnerving art of Helene Schjerfbeck". The Guardian. 6 July 2019.

Further reading[]

- Ahtola-Moorhouse, Leena, ed. Helene Schjerfbeck. 150 Years [exhibition catalogue, Konstmuseet Ateneum and Statens Konstmuseum] (2012)

- Marie Christine Tams, 'Dense Depths of the Soul: A Phenomenological Approach to Emotion and Mood in the Work of Helene Schjerfbeck', in Parrhesia; 13 (2011), p. 157–176

- Ahtola-Moorhouse, Lena: 'Schjerfbeck, Helene [Helena] (Sofia)', in Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press (6 February 2006) http://www.groveart.com/

- Roberta Smith, 'A Neglected Finnish Modernist Is Rediscovered', in The New York Times; sec. c:27. LexisNexis Academic. LexisNexis. 8 Feb. 2006 http://web.lexisnexis.com/universe

- S. Koja, Nordic Dawn Modernism's Awakening in Finland 1890-1920 [exhibition catalogue, Osterreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, and Gemeentemuseum The Hague] (2005)

- Ahtola-Moorhouse, L., 'Helene Schjerfbeck', in L'Horizon inconnu: l'art en Finlande 1870-1920 [exhibition catalogue] (1999)

- Bergström, Lea, and Cedercreutz-Suhonen, Sue: Helene Schjerfbeck, Malleja-Modeller-Models, WSOY, Helsinki, Finland, 2003.

- The Finnish National Gallery Ateneum. Helene Schjerfbeck. Trans. The English Centre. (1992)

- Ahtola-Moorhouse, L., ed. Helena Schjerfbeck. Finland's Modernist Rediscovered [exhibition catalogue, Phillips Collection Washington and National Academy of Design New York] (1992)

- Helene Schjerfbeck: Finland's best-kept secret Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide.

External links[]

Media related to Helene Schjerfbeck at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Helene Schjerfbeck at Wikimedia Commons

- 1862 births

- 1946 deaths

- Artists from Helsinki

- People from Uusimaa Province (Grand Duchy of Finland)

- Swedish-speaking Finns

- Finnish women painters

- 19th-century Finnish painters

- 20th-century Finnish painters

- 19th-century Finnish women artists

- 20th-century Finnish women artists

- Académie Colarossi alumni

- Finnish expatriates in France

- Finnish expatriates in Sweden