Henry Box Brown

Henry Box Brown | |

|---|---|

The Narrative of Henry Box Brown (1849) | |

| Born | Henry Brown c. 1815 Louisa County, Virginia, US |

| Died | June 15, 1897 (aged 81–82) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Abolitionist |

| Spouse(s) | First wife – Nancy (sold by slaveowner) Second wife – Jane Floyd |

Henry Box Brown (c. 1815 – June 15, 1897)[1] was a 19th-century Virginia slave who escaped to freedom at the age of 33 by arranging to have himself mailed in a wooden crate in 1849 to abolitionists in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

For a short time, Brown became a noted abolitionist speaker in the northeast United States. As a public figure and fugitive slave, Brown felt extremely endangered by passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which increased pressure to capture escaped slaves. He moved to England and lived there for 25 years, touring with an anti-slavery panorama, becoming a magician and showman.[2] Brown married and started a family with an English woman, Jane Floyd. This was Brown's second wife; his first wife, Nancy, had been sold by her slaveowner. Brown returned to the United States with his English family in 1875, where he continued to earn a living as an entertainer. He toured and performed as a magician, speaker, and mesmerist until at least 1889. The last decade of his life (1886–97) was spent in Toronto, where he died in 1897.[1]

Childhood and slavery[]

Henry Brown was born into slavery in 1815 or 1816 on a plantation called Hermitage in Louisa County, Virginia.[1] Henry may have remembered his parents fondly, stating that his mother was the one to instill Christian values into him. He is believed to have had at least two siblings, mentioning a brother and a sister in his autobiography.[3] At the age of 15, he was sent to work in a tobacco factory in Richmond.[4] In his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself, he describes his owner: "Our master was uncommonly kind, (for even a slaveholder may be kind) and as he moved about in his dignity he seemed like a god to us, but not with standing his kindness although he knew very well what superstitious notions we formed of him, he never made the least attempt to correct our erroneous impression, but rather seemed pleased with the reverential feelings which we entertained towards him."[5]

Escape[]

Brown was first married to a fellow slave, named Nancy, but their marriage was not recognized legally. They had three children born into slavery under the partus sequitur ventrem principle. Brown was hired out by his master in Richmond, Virginia, and worked in a tobacco factory, renting a house where he and his wife lived with their children.[6] Brown had also been paying his wife's master not to sell his family, but the man betrayed Brown, selling pregnant Nancy and their three children to a different slave owner.[1]

With the help of James C. A. Smith, a free black man,[4] and a sympathetic white shoemaker (and likely gambler) named Samuel A. Smith (no relation), Brown devised a plan to have himself shipped in a box to a free state by the Adams Express Company, known for its confidentiality and efficiency.[6] Brown paid US$86 (equivalent to $2,675 in 2020) (out of his savings of $166) to Samuel Smith. Smith went to Philadelphia to consult members of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society on how to accomplish the escape, meeting with minister James Miller McKim, William Still, and Cyrus Burleigh. He corresponded with them to work out the details after returning to Richmond. They advised him to mail the box to the office of Quaker merchant Passmore Williamson, who was active with the Vigilance Committee.[6]

To get out of work the day he was to escape, Brown burned his hand to the bone with sulfuric acid. The box in which Brown was shipped was 3 by 2.67 by 2 feet (0.91 by 0.81 by 0.61 m) and displayed the words "dry goods" on it. It was lined with baize, a coarse woolen cloth, and he carried only a small portion of water and a few biscuits. There was a single hole cut for air, and it was nailed and tied with straps.[4] Brown later wrote that his uncertain method of travel was worth the risk: "if you have never been deprived of your liberty, as I was, you cannot realize the power of that hope of freedom, which was to me indeed, an anchor to the soul both sure and steadfast."[7]

During the trip, which began on March 29, 1849,[6] Brown's box was transported by wagon, railroad, steamboat, wagon again, railroad, ferry, railroad, and finally delivery wagon, being completed in 27 hours. Despite the instructions on the box of "handle with care" and "this side up," several times carriers placed the box upside-down or handled it roughly. Brown remained still and avoided detection.

The box was received by Williamson, McKim, William Still, and other members of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee on March 30, 1849, attesting to the improvements in express delivery services.[6] When Brown was released, one of the men remembered his first words as "How do you do, gentlemen?" He sang a psalm from the Bible, which he had earlier chosen to celebrate his release into freedom.[8]

In addition to celebrating Brown's inventiveness, as noted by Hollis Robbins, "the role of government and private express mail delivery is central to the story and the contemporary record suggests that Brown's audience celebrated his delivery as a modern postal miracle." The government postal service had dramatically increased communication and, despite southern efforts to control abolitionist literature, mailed pamphlets, letters and other materials reached the South.[6]

Cheap postage, Frederick Douglass observed in The North Star, had an "immense moral bearing". As long as federal and state governments respected the privacy of the mails, everyone and anyone could mail letters and packages; almost anything could be inside. In short, the power of prepaid postage delighted the increasingly middle-class and commercial-minded North and increasingly worried the slave-holding South.[6]

Brown's escape highlighted the power of the mail system, which used a variety of modes of transportation to connect the East Coast. The Adams Express Company, a private mail service founded in 1840, marketed its confidentiality and efficiency. It was favored by abolitionist organizations and "promised never to look inside the boxes it carried."[6]

Life in freedom[]

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Brown became a well-known speaker for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and got to know Frederick Douglass. He was nicknamed "Box" at a Boston antislavery convention in May 1849, and thereafter used the name Henry Box Brown. He published two versions of his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown; the first, written with the help of Charles Stearns and conforming to expectations of the slave narrative genre,[6] was published in Boston in 1849. The second was published in Manchester, England, in 1851, after he had moved there. While on the lecture circuit in the northeastern United States, Brown developed a moving panorama with his partner James C. A. Smith. They separated in 1851.[6]

Douglass wished that Brown had not revealed the details of his escape, so that others might have used it. When Samuel Smith attempted to free other slaves in Richmond in 1849, they were arrested.[9] The year of his escape, Brown was contacted by his wife's new owner, who offered to sell his family to him, but the newly free man declined.[10] This was an embarrassment within the abolitionist community, which tried to keep the information private.[6]

Brown is known for speaking out against slavery and expressing his feelings about the state of America. In his Narrative, he offers a cure for slavery, suggesting that slaves should be given the vote, a new president should be elected, and the North should speak out against the "spoiled child" of the South.[11]

After passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which required cooperation from law enforcement officials to capture refugee slaves even in free states, Brown moved to England for safety, as he had become a known public figure. He toured Britain with his antislavery panorama for the next ten years, performing several hundred times a year. To earn a living, Brown also entered the British show circuit for 25 years, until 1875, after leaving the abolitionist circuit following the start of the American Civil War.[9] In 1857, as Cutter documented in her book, The Illustrated Slave (2017), Brown acted in several plays written expressly for him by a British playwright – E.G. Burton – but his acting career appears to have been short-lived.[12] In the 1860s, he began performing as a magician with acts as a mesmerist and conjuror, under the show names of "Prof. H. Box Brown" and the "African Prince".[13]

While in England, Brown married Jane Floyd, a white Cornish tin worker's daughter, in 1855 and began a new family.[14] In 1875, he returned with his family to the U.S. with a group magic act. A later report documented the Brown Family Jubilee Singers.[1]

Death[]

As the scholar Martha J. Cutter first documented in 2015, Henry Box Brown died in Toronto on June 15, 1897.[1] Tax records and other documents indicate that he continued to perform into the early 1890s, but no performance records from that decade have been found.[1] The last known performance by Brown is a newspaper account of a performance with his daughter Annie and wife Jane[1] in Brantford, Ontario, Canada, dated February 26, 1889.[15]

Legacy[]

Samuel Alexander Smith attempted to ship more enslaved from Richmond to liberty in Philadelphia, but was discovered and arrested. As for James C. A. Smith, he too was arrested for attempting another shipment of slaves.[4]

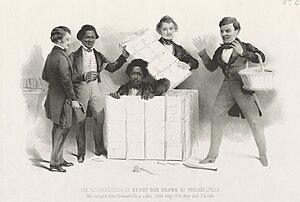

- The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia, a lithograph by Samuel Rowse, depicted Henry Brown emerging from the shipping box into freedom in Philadelphia. The lithograph was published to help raise funds to produce Brown's anti-slavery panorama. One of three known originals is preserved in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond.[16]

- A monument to Henry "Box" Brown is located along the Canal Walk in downtown Richmond, Virginia; it is a metal reproduction of the box in which Brown escaped.[17]

- In 2012, Louisa County set a historical marker honoring Henry Box Brown and his escape from slavery.[18]

- The Unboxing of Henry Brown (2003) is a biography by Jeffrey Ruggles.[10]

- Ellen Levine wrote a children's picture book entitled Henry's Freedom Box (2007) based upon Brown's life. It was illustrated by Kadir Nelson and was awarded the Caldecott Honor.[19]

- Tony Kushner wrote a play entitled Henry Box Brown, which premiered in 2010.[20]

- Doug Peterson wrote a historical novel based on Henry Brown called The Disappearing Man (2011).[21]

- Sally M. Parker wrote a children's book, Freedom Song: The Story of Henry "Box" Brown (2012), illustrated by Sean Qualls.[22]

- Henry Box Brown is the subject of a 2012 film, Box Brown, by director Rob Underhill.[23]

- Playwright Mike Wiley wrote a one-man show about the life of Henry Box Brown entitled One Noble Journey.[24]

- In 2014, Illustrator and historian Joel Christian Gill published a comic novel called Strange Fruit, Volume I: Uncelebrated Narratives from Black History, which included Brown's story.[25]

- On the song "Diasporal Histories" by Professor A.L.I. released on the XFactor album in 2015, he interweaves the slave narratives of Henry "Box" Brown, Solomon Northup, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and the fictionalized narrative of Eliza who escapes slavery through an icy river. He says of Brown, "Henry Brown, boxed himself up to Boston! (a reference to the north)".[26]

- Henry Box Brown is the subject of a sequence of poems in Olio (2016) by Tyehimba Jess. The poems are adapted from John Berryman's The Dream Songs.

- Henry Box Brown and his story is featured on the 2019 Kevin Hart Netflix Original “Kevin Hart’s Guide To Black History”.

Psalm[]

Song (modeled after Psalm 40), sung by Mr. Brown on being removed from the Box:[27][1]

I waited patiently for the Lord

And he, in kindness to me, heard my calling

And he hath put a new song into my mouth

Even thanksgiving — even thanksgiving

Unto our God!

Blessed-blessed is the man

That has set his hope, his hope in the Lord!

O Lord! my God! great, great is the wondrous work

Which thou hast done!

If I should declare them — and speak of them

They would be more than I am able to express.

I have not kept back thy love, and kindness, and truth,

From the great congregation!

Withdraw not thou thy mercies from me,

Let thy love, and kindness, and thy truth, always preserve me

Let all those that seek thee be joyful and glad!

Be joyful and glad!

And let such as love thy salvation

Say always — say always

The Lord be praised!

The Lord be praised!

See also[]

- List of slaves

- Slavery in the United States

- Abolitionism in the United States

- Fugitive slaves in the United States

- Fugitive slave laws in the United States

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Cutter, Martha (2015). "Will the real Henry Box Brown please stand up?". Common-place: Journal of early American life.

- ^ Robbins 2009, p. 5.

- ^ ERNEST, JOHN, editor. Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself. University of North Carolina Press, 2008, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807888858_ernest.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Walls, Bryan. "Henry 'Box' Brown Freedom Marker: Courage and Creativity". PBS.

- ^ Brown 1851, p. 5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Robbins 2009.

- ^ Brown 1851, p. 60.

- ^ Brown 1851.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Spencer, Suzette. "Henry Box Brown". Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ruggles 2003.

- ^ Brown 1851, pp. 66-90.

- ^ Cutter, Martha J. (August 15, 2017). The Illustrated Slave: Empathy, Graphic Narrative, and the Visual Culture of the Transatlantic Abolition Movement, 1800-1852. ISBN 9780820351162.

- ^ Spencer, Suzette. "Henry Box Brown (1815 or 1816–after February 26, 1889)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Green, Jeffrey. "Henry 'Box' Brown, escaped slave turned showman". Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Spencer, Suzette. "Henry Box Brown (1815 or 1816 – after February 26, 1889)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "Henry Box Brown". The National Great Blacks in Wax Museum. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ "Box Brown Plaza – Riverfront Canal Walk". www.rvariverfront.com. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ Historical Marker Honors Local Man Who Escaped Slavery. Newsplex.com (May 22, 2012). Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ^ Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938–Present | Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). Ala.org. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (October 4, 2010). "An Unlikely Tony Kushner World Premiere, Courtesy of NYU". The New York Times.

- ^ Peterson, Doug (2011). The Disappearing Man. Kingstone Media. ISBN 9781936164332.

- ^ Qualls, Sean. (March 5, 2012) News from Sean Qualls: Another *Starred Review (BCCB) for Freedom Song. Seanqualls.blogspot.com. March 5, 2012.

- ^ Box Brown, Robunderhill.wix.com. Retrieved on December 7, 2013.

- ^ "Niagara Life Magazine - Lighting the spark of imagination". www.niagaralifemag.com. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ NPR Staff (February 14, 2015). "'Strange Fruit' Shares Uncelebrated, Quintessentially American Stories". NPR News: Code Switch. National Public Radio. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "Diasporal Histories". ProfessorALI.com. January 19, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Henry (1849). "Song, sung by Mr. Brown on being removed from the box". Boston, MA: Laing's Stream Press.

Bibliography[]

- Brown, Henry Narrative of Henry Box Brown, Who Escaped from Slavery, Enclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide Boston: Brown and Stearns, 1849. Documenting the American South website, University of North Carolina.

- Brown, Henry Box (1851). Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself (2nd ed.). Manchester: Lee & Glynn. Documenting the American South website, University of North Carolina.

- Chater, Kathleen Untold Histories: Black People in England and Wales During the Period of the British Slave Trade, c. 1660-1807 Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010.

- Chater, Kathleen Henry Box Brown: From Slavery to Show Business McFarland & Company, Inc, Jefferson, NC, 2020.

- Cutter, Martha J. The Illustrated Slave: Empathy, Graphic Narrative, and the Visual Culture of the Transatlantic Abolition Movement, 1800–1852. University of Georgia Press, 2017.

- Cutter, Martha J. Will the Real Henry "Box" Brown Please Stand Up? Common-Place: The Journal of Early American Life, Fall 2015.

- Robbins, Hollis (2009). "Fugitive Mail: The Deliverance of Henry "Box" Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics". American Studies. 50: 5. doi:10.1353/ams.2011.0045. S2CID 142902898.

- Ruggles, Jeffrey (2003). The Unboxing of Henry Brown. Library of Virginia. ISBN 9780884902003.

External links[]

- African American Voices, Digital History website

- African American History; Henry Box Brown webpage, African American Registry

- "Henry Box Brown", Virginia Historical Society

- Henry "Box" Brown Wax Figure at The National Great Blacks in Wax Museum, Baltimore, Maryland

- "When special delivery meant deliverance for a fugitive slave", New York Times blog, February 26, 2010

- "Henry Box Brown" in Union or Secession: Virginians Decide, at Library of Virginia

- NEH's EDSITEment lesson plan Henry "Box" Brown's Narrative: Creating Original Historical Fiction

- NPR interview with Brown biographer Jeffrey Ruggles

- Will the Real Henry "Box" Brown Please Stand Up?, Article by Martha J. Cutter documenting Box Brown's date of death.

- 1815 births

- 1897 deaths

- American autobiographers

- Activists from Philadelphia

- People from Louisa County, Virginia

- American emigrants to Canada

- African-American abolitionists

- Fugitive American slaves

- African-American history of Virginia

- American magicians

- African-American Christians

- People who wrote slave narratives

- American expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Christian abolitionists

- Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania

- 19th-century American slaves