High Plains Drifter

| High Plains Drifter | |

|---|---|

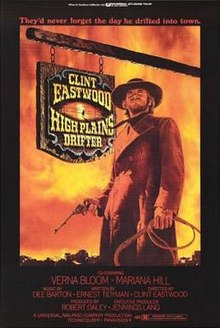

Theatrical release poster by Ron Lesser | |

| Directed by | Clint Eastwood |

| Written by | Ernest Tidyman |

| Produced by | Robert Daley |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Bruce Surtees |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Dee Barton |

Production company | The Malpaso Company |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.5 million[2] |

| Box office | $15.7 million[3] |

High Plains Drifter is a 1973 American Western film directed by Clint Eastwood, written by Ernest Tidyman, and produced by Robert Daley for The Malpaso Company and Universal Pictures. The film stars Eastwood as a mysterious stranger who metes out justice in a corrupt frontier mining town.[4] The film was influenced by the work of Eastwood's two major collaborators, film directors Sergio Leone and Don Siegel.[5] In addition to Eastwood, the film also co-stars Verna Bloom, Mariana Hill, Mitchell Ryan, Jack Ging, and Stefan Gierasch.

The film was shot on location on the shores of Mono Lake, California. Dee Barton wrote the film score. The film was critically acclaimed at the time of its initial release and remains popular.

Plot[]

An unnamed man rides out of the desert into the isolated mining town of Lago in the American Old West. Three men taunt him, and he kills all three with little effort. When townswoman Callie Travers loudly insults him, he rapes her in the livery stable. That night, in his hotel room, the Stranger dreams of Jim Duncan, a federal marshal, being whipped to death by outlaws Stacey Bridges and brothers Dan and Cole Carlin, as Lago's citizens watch in silence.

The next day, the Lago town government offers the Stranger anything he wants to protect the town from Bridges and the Carlins, who will soon be released from prison after they were falsely convicted for stealing a gold ingot. The Stranger accepts the job and takes full advantage of the deal: he appoints a downtrodden dwarf named Mordecai as both sheriff and mayor, provides a Native American and his children with supplies when the shopkeeper refuses to serve them, gets a new saddle and boots, and forces the saloon to serve everyone free drinks. The Stranger tries to form a company of volunteers to defend the town, but quickly realizes that none are competent to handle the job. He orders the hotel owners and their guests to vacate the premises, leaving him its sole occupant. The owners, Lewis Belding and his wife Sarah, are furious, along with many other town residents.

Callie and several men conspire to do away with the Stranger. She has sex with the Stranger in his room, before slipping out when he's asleep as the others enter. As they unknowingly beat a dummy in the bed, the Stranger tosses a stick of dynamite into the room, wrecking the hotel, before gunning down most of his attackers. He drags Sarah, kicking and screaming, into her bedroom (the only room that wasn't damaged) and they sleep together. The next morning, while discussing what happened to Bridges and the Carlin brothers, Sarah tells the Stranger that Duncan cannot rest in peace because the town threw him in an unmarked grave.

The stranger orders that every building in town be painted blood red. Then, without explanation, he mounts his horse and rides out of town, having painted over the town sign with a single word: "Hell." Meanwhile, Bridges and the Carlins murder a party of travelers and steal their horses and guns. The Stranger finds them outside of town and harasses them with dynamite and rifle fire, making the outlaws believe the townspeople are responsible. Returning to Lago, the Stranger inspects the preparations—the entire town painted red, armed men on rooftops, picnic tables laden with food and drink, and a big "WELCOME HOME BOYS" banner overhead—then he remounts and departs again.

The outlaws arrive and easily overcome the inept resistance of the townspeople, setting fire to the town and killing the mine owner who framed them. But that night, as the terrified citizens huddle in the trashed saloon, the Stranger kills the outlaws one by one. Belding tries to ambush the Stranger with a shotgun, but Mordecai shoots Belding in the back, killing him.

As the townspeople clean up and Sarah prepares to leave town, the Stranger departs. "I never did know your name," Mordecai says. "Yes, you do," the Stranger replies, vanishing into the heat of the desert. Bewildered, Mordecai finishes a new marker for the grave of Marshal Jim Duncan.

Cast[]

- Clint Eastwood as The Stranger

- Verna Bloom as Sarah Belding

- Mariana Hill as Callie Travers

- Billy Curtis as Mordecai

- Mitch Ryan as Dave Drake

- Jack Ging as Morgan Allen

- Stefan Gierasch as Mayor Jason Hobart

- Ted Hartley as Lewis Belding

- Geoffrey Lewis as Stacey Bridges

- Dan Vadis as Dan Carlin

- Anthony James as Cole Carlin

- Walter Barnes as Sheriff Sam Shaw

- Paul Brinegar as Lutie Naylor

- Richard Bull as Asa Goodwin

- Robert Donner as Preacher

- John Hillerman as Bootmaker

- John Quade as Freight Wagon Operator

- Buddy Van Horn as Marshal Jim Duncan

- William O'Connell as the Barber

- as Tommy Morris

- as Billy Borders

- Russ McCubbin as Fred Short

Production[]

Eastwood reportedly liked the offbeat quality of the film's original nine-page proposal and approached Universal with the idea of directing it. It is the first Western film that he both directed and starred in. Under a joint production between Malpaso and Universal, the original screenplay was written by Ernest Tidyman, who had won a Best Screenplay Oscar for The French Connection.[6] Tidyman's screenplay was inspired by the real-life murder of Kitty Genovese in Queens in 1964, which eyewitnesses reportedly stood by and watched. Holes in the plot were filled in with black humor and allegory, influenced by Sergio Leone.[6] An uncredited rewrite of the script was provided by Dean Riesner, screenwriter of other Eastwood projects.

Universal wanted Eastwood to shoot the feature on its back lot, but Eastwood opted instead to film on location. After scouting locations alone in a pickup truck in Oregon, Nevada and California,[7] he settled on the "highly photogenic" Mono Lake area.[8] Over 50 technicians and construction workers built an entire town—14 houses, a church, and a two-story hotel—in 18 days, using 150,000 feet of timber.[8] Complete buildings, rather than facades, were built, so that Eastwood could shoot interior scenes on the site. Additional scenes were filmed at Reno, Nevada's Winnemucca Lake and California's Inyo National Forest.[8] The film was completed in six weeks, two days ahead of schedule, and under budget.[9]

The character of Marshal Duncan was played by Buddy Van Horn, Eastwood's long-time stunt double, to suggest that he and the Stranger could be the same person. In an interview, Eastwood said that earlier versions of the script made the Stranger the dead marshal's brother. He favored a less explicit and more supernatural interpretation, and excised the reference.[10] The Italian, Spanish, French and German dubbings restored it.[11] "It's just an allegory," Eastwood said, "a speculation on what happens when they go ahead and kill the sheriff, and somebody comes back and calls the town's conscience to bear. There's always retribution for your deeds."[10] The graveyard set featured in the film's final scene included tombstones inscribed "Sergio Leone" and "Don Siegel" as a humorous tribute to the two influential directors.[5]

Reception[]

Universal released the R-rated High Plains Drifter in the United States in April 1973, and the film eventually grossed $15.7 million domestically,[3] ultimately making it the sixth-highest grossing Western in North America in the decade of the 1970s and the 20th highest-grossing film released in 1973. The film was well received by many critics, and rates 93% positive on Rotten Tomatoes based on 27 reviews.[12] On Metacritic the film has a score 69% based on reviews from 10 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[13]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "part ghost story, part revenge Western, more than a little silly, and often quite entertaining in a way that may make you wonder if you lost your good sense."[14] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 3 stars out of 4 and wrote, "What does work very well indeed is Eastwood's presence, personal style, and direction. Though his laconic sense of humor often drags out the pacing of the movie, Eastwood uses his camera with intelligence and flair."[15] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety called it "a nervously humorous, self-conscious near satire on the prototype Clint Eastwood formula of the avenging mysterious stranger. Ernest Tidyman's script has some raw violence for the kinks, some dumb humor for audience relief, and lots of arch characterizations befitting the serio-comic-strip nature of the plot."[16] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called it "a stylized, allegorical western of much chillingly paranoid atmosphere and considerable sardonic humor that confirms Eastwood's directorial flair. It's also a pretty violent business that won't disappoint the millions who flocked to the Leone westerns."[17] Tom Zito of The Washington Post called it "an enjoyable, well-constructed work that suffers only from a slightly tedious tone that makes the film seem longer than its 105 minutes."[18]

The film had its share of detractors. Some critics thought Eastwood's directing derivative; Arthur Knight in Saturday Review remarked that Eastwood had "absorbed the approaches of Siegel and Leone and fused them with his own paranoid vision of society".[19] Jon Landau of Rolling Stone concurred, noting "thematic shallowness" and "verbal archness"; but he expressed approval of the dramatic scenery and cinematography.[19] Nigel Andrews of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that "after Play Misty For Me, High Plains Drifter emerges as a disappointingly sterile exercise in style, suggesting that the first thing Eastwood should do as a director is forget the lessons he has learned from other film-makers and start to forge a convincing style of his own."[20] John Wayne criticized the film's iconoclastic approach; in a letter to Eastwood, he wrote, "That isn't what the West was all about. That isn't the American people who settled this country."[21]

The film was recognized by American Film Institute in 2008 on AFI's 10 Top 10 in the category "Nominated Western Film".[22]

Home media[]

High Plains Drifter was first released on DVD by Universal Studios Home Video on February 24, 1998.[23] It made its Blu-ray debut on October 15, 2013, with a newly remastered transfer,[24] and was reissued on October 27, 2020, by Kino Lorber with commentary tracks and new interviews.[25]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "High Plains Drifter – Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ Box Office Information for High Plains Drifter. Archived October 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine The Wrap. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Box Office Information for High Plains Drifter. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ Flynn, Erin E. (2014). "The Representation of Justice in Eastwood's High Plains Drifter". In McClelland, Richard T.; Clayton, Brian B. (eds.). The Philosophy of Clint Eastwood. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-081314264-7. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kaminsky, Stuart (1975). Clint Eastwood. Signet Books. ISBN 978-0-451-06159-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGilligan (1999), p. 221

- ^ Gentry, p. 63

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hughes, p. 28

- ^ Eliot (2009), p. 144

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hughes, pp. 30–31

- ^ Clint Eastwood. Guardian interviews, retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ "High Plains Drifter". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ "High Plains Drifter". Metacritic.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (April 20, 1973). "'High Plains Drifter' Opens on Screen". The New York Times. 21.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (April 20, 1973). "Mortal combat, East and West..." Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 3.

- ^ Murphy, Arthur D. (March 28, 1973). "Film Reviews: High Plains Drifter". Variety. 24.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (April 6, 1973). "Clint Back in Saddle in 'Drifter'". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 17.

- ^ Zito, Tom (May 29, 1973). "Eastwood Again". The Washington Post. B9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGilligan, p. 223

- ^ Andrews, Nigel (August 1973). "High Plains Drifter". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 40 (475): 170.

- ^ Peter Biskind, "Any Which Way He Can", Premiere, April 1993.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Eastwood, Clint (February 24, 1998), High Plains Drifter, Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, ISBN 0783225725

- ^ Eastwood, Clint (October 15, 2013), High Plains Drifter, Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, retrieved May 21, 2018

- ^ "Kino: Clint Eastwood's High Plains Drifter Detailed for Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. July 21, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

Bibliography[]

- Cornell, Drucilla (2009). Clint Eastwood and Issues of American Masculinity. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0823230143.

- Eliot, Marc (2009). American Rebel: The Life of Clint Eastwood. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-33688-0.

- Gentry, Ric (1999). "Director Clint Eastwood: Attention to Detail and Involvement for the Audience". In Robert E., Kapsis; Coblentz, Kathie (ed.). Clint Eastwood: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 62–75. ISBN 1-57806-070-2.

- Girgus, Sam (2014). "An American Journey: Issues and Themes". Clint Eastwood's America. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0745656489.

- Green, Philip (1998). Cracks in the Pedestal Ideology and Gender in Hollywood. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1558491201.

- Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra (2011). Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786449613.

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- Ruffles, Tom (2004). Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0786484217.

- White, Mike (2013). Cinema Detours. Morrisville: Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1300981176.

Further reading[]

- Guérif, François (1986). Clint Eastwood, p. 94. St Martins Pr. ISB

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: High Plains Drifter |

- 1973 films

- English-language films

- 1973 Western (genre) films

- American films

- American films about revenge

- American supernatural thriller films

- American vigilante films

- American Western (genre) films

- Films about rape

- Films directed by Clint Eastwood

- Films set in California

- Films shot in California

- Malpaso Productions films

- Revisionist Western (genre) films

- Universal Pictures films