Hisham's Palace

قصر هشام | |

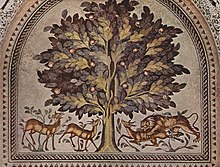

The "Tree of Life" mosaic in the audience room of the bath house. | |

Shown within State of Palestine | |

| Location | Jericho Governorate, West Bank |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°52′57″N 35°27′35″E / 31.88250°N 35.45972°ECoordinates: 31°52′57″N 35°27′35″E / 31.88250°N 35.45972°E |

| Type | Settlement |

Hisham's Palace (Arabic: قصر هشام Qaṣr Hishām or Arabic: خربة المفجر Khirbat al-Mafjar) is an important early Islamic archaeological site of the Umayyad dynasty from the first half of the 8th century, one of the so-called desert castles. It is located five km north of the town of Jericho, at Khirbat al-Mafjar in the West Bank.[1] Spreading over 60 hectares (150 acres),[1] it consists of three main parts: a palace, an ornate bath complex, and an agricultural estate. Also associated with the site is a large park or agricultural enclosure (ḥayr) which extends east of the palace. An elaborate irrigation system provided the complex with water from nearby springs.

History of study[]

The site was discovered in 1873.[1] The northern area of the site was noted, but not excavated, in 1894 by F.J Bliss,[2] but the major source of archaeological information comes from the excavations of Palestinian archaeologist, Dimitri Baramki between 1934 and 1948.[3] In 1959 Baramki's colleague, colonial administrator for the British Mandate government Robert W. Hamilton, published the major work on Hisham's Palace, Khirbat al-Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordanian Valley. Baramki's archaeological research is unfortunately absent from this volume, and as such, Hamilton's analysis is exclusively art historical. Baramki's research on the archaeological aspects of the site, particularly the ceramics, was published in various preliminary reports and articles in the Quarterly of the Palestinian Department of Antiquities.[4] Many of the finds from Baramki and Hamilton's excavations are now held in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem.

In 2006, new excavations were carried out under the direction of Dr. Hamdan Taha of the Palestinian National Authority's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. Current research is being conducted by the Jericho Mafjar Project, a collaboration between the ministry and archaeologists from the University of Chicago.

In 2015, an agreement was signed between the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and the Japan International Cooperation Agency to enable the 825 square meter mosaic in the palace, one of the largest in the world, to be uncovered and readied for display.[1]

Context[]

It is difficult to establish a secure historical framework for Hisham's Palace. No textual sources reference the site, and archaeological excavations are the only source of further information. An ostracon bearing the name "Hisham" was found during the course of Baramki's excavations. This was interpreted as evidence for the site's construction during the reign of the caliph Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Malik. Robert Hamilton subsequently argued that the palace was a residence of al-Walid b. al-Yazid, a nephew of Hisham who was famous for his extravagant lifestyle.[5] Archaeologically it is certain that the site is a product of the Umayyad dynasty in the first half of the 8th century, although the specifics of its patronage and use remain unknown.

As an archaeological site, Hisham's Palace belongs to the category of desert castles. These are a collection of monuments dating to the Umayyad dynasty and found throughout Syria, Jordan, Israel, and the West Bank. Although there is great variation in the size, location, and presumed function of these different sites, they can be connected to the patronage of different figures in the Umayyad ruling family.[6] Some of the desert castles, for example Qasr Hallabat or Qasr Burqu, represent Islamic occupations of earlier Roman or Ghassanid structures. Other sites like Qastal, Qasr Azraq, or al-Muwaqqar are associated with trade routes and scarce water resources. With a few exceptions, the desert castles conform to a common template consisting of a square palace similar to Roman forts, a bath house, water reservoir or dam, and often an agricultural enclosure. Various interpretations for the desert castles exist, and it is unlikely that one single theory can explain the variety observed in the archaeological record.

Architecture[]

The palace, bath complex, and external mosque are enclosed by a retaining wall. The southern gate was known from Baramki's excavations, but the recent discovery of a northern gate in alignment indicates that the development of Hisham's Palace was conceived of as a complete unit to be constructed at once.[7]

Palace[]

The largest building at the site is the palace, a roughly square building with round towers at the corners. It originally had two stories. Entrance was through a gate on the center of the east side. The inner rooms were aligned around a central paved portico, which featured an underground cellar or , for refuge from the heat. The room to the south of the portico was a mosque with a mihrab built into the outer wall.[8]

Outer pavilion and mosque[]

East of the palace entrance was a pavilion and fountain. A second, larger mosque was located to the northeast of the palace entrance.[8]

Bath complex[]

The bath complex is located just north of the palace across an open area. This free-standing structure is approximately thirty meters square, and three of its sides feature round exedrae which project out from the building. The east face of the bath had an ornate entrance in its center, flanked by exedrae. Inside the main square hall was a pool. The entire interior floor surface of the bath complex was paved with spectacular mosaic decoration. A special reception room, or diwan, was entered from the northwest corner. The floor of this room was paved with the famous "tree of life" mosaic, depicting a lion and gazelles at the foot of a tree. The actual bathing rooms were attached to the northern wall of the complex, and were heated from below the floor by hypocausts.[8]

Agricultural annex[]

To the north of the bath complex are the ruins of a large square structure which has clearly gone through many phases of reuse and reconstruction. This part of the site was initially assumed to be a khan or caravanserai, but recent excavations have indicated that the northern area had an agricultural function connected to the hayr or agricultural enclosure during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods.

Decoration[]

The decorative elements at Hisham's Palace are some of the finest representations of Umayyad period art and are well documented in the publications of Robert Hamilton.

Mosaics[]

The most famous artistic aspect of the site is the "tree of life" mosaic in the diwan of the bath complex, although the mosaic floor of the main bath hall is no less impressive. All of the mosaics found at Hisham's Palace are of very high quality and feature a wide variety of colors and figural motifs.

Carved stucco[]

The carved stucco found at the site is also of exceptional quality. Of particular note is the statue depicting a male figure with a sword, often presumed to be the caliph, which stood in a niche above the entrance to the bath hall. Additional male and female figures carved in stucco, some semi-nude, adorn the bath complex. Geometric and vegetal patterns are also quite common.

While Hamilton described the carvings at Hisham's Palace as amateurish and chaotic, many subsequent art historians have noted similarities with Iranian themes. Hana Taragan has argued that the artistic themes seen at the site are Levantine examples of an Islamic visual language of power that coalesced from Sasanian influences in Iraq.[9] Priscilla Soucek has also drawn attention to the site's representation of the Islamic myth of Solomon.[10]

Post-Umayyad occupational history[]

The site is commonly thought to have been destroyed and abandoned by the earthquake of 747/8, but an analysis of Baramki's detailed reporting shows that this is incorrect. Instead the ceramic record indicates that the occupation continued through the Ayyubid-Mamluk period, with a significant phase of occupation between 900–1000 during the Abbasid and Fatimid periods.[11] Further excavations will no doubt contribute to a more detailed picture of the site's continued use through different periods.

Heritage[]

Hisham's Palace is one of the most important Islamic monuments in Palestine, and is a major attraction for both visitors and Palestinians. In 2010, according to figures collected by the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, the site received 43,455 visitors. The site is a common field trip destination for Palestinian schoolchildren. Foreign visitors who enter Palestine through the nearby Allenby Bridge often make Hisham's Palace their first stop. The site has been visited by foreign dignitaries, and was the set for a production of Shakespeare's Richard II in 2012.[12]

According to Global Heritage Fund (GHF), the rapid urban development of Jericho, as well as expansion of agricultural activity in the area, are limiting archaeologists' access to the site, much of which remain unexplored. Conservation efforts aimed at protecting important structures have been hindered by lack of resources. In a 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, GHF identified Hisham's Palace as one of 12 worldwide heritage sites most "On the Verge" of irreparable loss and destruction.[13] H. Taha, director of antiquities has published reports concerning the preservation of this and other sites in the Jericho region.[14]

Gallery[]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Japan to fund uncovering of large Jericho mosaic". Ma'an News Agency. 21 September 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ Bliss 1894.

- ^ Whitcomb, Donald. "Dimitri Baramki: Discovering Qasr Hisham" (pdf). Journal of Palestine Studies. Institute for Palestine Studies. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ Whitcomb and Taha 2013

- ^ Hamilton 1988

- ^ Bacharach 1996.

- ^ "Area 1 Excavations". Jericho Mafjar Project. Palestinian National Authority. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Baer, "Khirbat al-Mafjar"

- ^ Taragan 2003

- ^ Soucek 1993

- ^ Whitcomb 1988

- ^ Browning, Noah (23 April 2012). "Shakespeare in Jericho echoes year of Arab strife". Reuters. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ "Saving Our Vanishing Heritage – Global Heritage in the Peril: Sites on the Verge". Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Taha 2005

References[]

- Baer, Eva. "Khirbat al-Mafjar." Encyclopaedia of Islam 2nd ed.

- Bliss, F.J. (1894) "Notes on the Plain of Jericho." Palestinian Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement. 175–183.

- Bacharach, Jere. (1996) "Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage." Muqarnas Vol. 13: 27–44.

- Hamilton, Robert W. (1959) Khirbat al-Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Hamilton, Robert W. (1988) Walid and his Friends: An Umayyad Tragedy Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Soucek, Priscilla. (1993) "Solomon's Throne/Solomon's Bath: Model or Metaphor." Ars Orientalis Vol. 23: 109–134.

- Taha, Hamdan. (2005) "Rehabilitation of Hisham's Palace in Jericho." in F. Maniscalco ed. Tutela, Conservazione e Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Culturale della Palestina. Naples. 179–188.

- Taragan, Hana. (2003) "Atlas Transformed--Interpreting the 'Supporting Figures' in the Umayyad Palace at Khirbat al-Mafjar." East and West Vol. 53: 9–29.

- Whitcomb, Donald. (1988) "Khirbat al-Mafjar Reconsidered: The Ceramic Evidence". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 271: 51–67.

- Whitcomb, Donald and Taha, Hamdan. (2013) ""Khirbat al-Mafjar and Its Place in the Archaeological Heritage of Palestine" Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 1(1): 54–65.

- Whitcomb, Donald and Taha, Hamdan. (2014) The Mosaics of Khirbet el-Mafjar Hisham's Palace

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khirbat al Mafjar. |

- The Jericho Mafjar Project

- Khirbat al-Mafjar at ArchNet.

- Explore Hisham's Palace with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network

- Dimitri Baramki: Discovering Qasr Hisham, by Donald Whitcomb, 2014, Jerusalem Quarterly, Institute for Palestine Studies

- Umayyad palaces

- Archaeological sites in the West Bank

- Buildings and structures in Jericho