Historic Deerfield

Old Deerfield Historic District | |

Wells-Thorn House | |

| |

| Location | Deerfield, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Built | 1650 |

| Architect | Benjamin, Asher; et al. |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000774[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | October 9, 1960, see [1] |

Historic Deerfield is a museum dedicated to the heritage and preservation of Deerfield, Massachusetts, and history of the Connecticut River Valley. Its historic houses, museums, and programs provide visitors with an understanding of New England's historic villages and countryside. It is located in the village of Old Deerfield which has been designated a National Historic Landmark District (as the Old Deerfield Historic District), and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The museum also hosts the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife.

Sites[]

Eleven historic house museums are located in Historic Deerfield. Most are viewed on guided tours. A modern museum and a visitors center are part of the complex. The museum offers special exhibitions, family activities, workshops and seminars on historic subjects, and a gift shop. The is available for visitors.

- Ashley House is the 1734 home of Deerfield's 18th-century minister, with furnishings of the Connecticut River elite and English ceramics.

- Allen House is a 1734 home that was the 20th-century residence of Historic Deerfield's founders, Henry and Helen Flynt. The Flynt family renovated the house in 1945. The home features their personal collection of American antiques and is open by arrangement.

- Stebbins House is the 1799 home of Asa Stebbins. The brick house features Federal period decorations, including neoclassical furnishings dating from 1790 to 1830.[2] Highlights include French scenic wallpaper panels manufactured by Joseph Dufour et Cie that depict the voyages of Captain Cook. This house is open for self-guided tours.

- Barnard Tavern is a 1795 tavern currently closed for restoration and reinterpretation. It is scheduled to reopen in fall 2013.

- Dwight House is a c. 1754 house built in Springfield, Massachusetts. It was moved to Deerfield in 1950 when it was threatened with demolition. The house reopened in 2009 as a museum of historic trades.

- Frary House is a c. 1750 home interpreted to depict the 1890s home of Miss C. Alice Baker, who restored the house in 1892. Displays include New England antiques, Arts and Crafts needlework, ironware, and basketry. The house features Miss Baker's role in fostering the Colonial Revival in Deerfield.

- Hall Tavern Visitor Center was originally built c. 1785 in Charlemont, Massachusetts; a ballroom wing was added around 1815. The building was moved to Deerfield and converted to a visitors center.

- Sheldon House was built in 1754–55 and is interpreted to the period of 1780 to 1810. This house is open for self-guided tours.

- Wells-Thorn House is a 1747 house featuring rooms demonstrating different periods and lifestyles from 1725 to the 1850s.

- Williams House is a c. 1730 house extensively renovated in 1817. The house features Federal-style furnishings and decorations.

- Flynt Center of Early New England Life is a modern museum with changing exhibits of history, heritage crafts, decorative arts, and other topics.

History[]

Historic Deerfield was founded by Henry and Helen Flynt, who had visited Deerfield in 1936 when their son attended Deerfield Academy. It was originally called "The Heritage Foundation" (not to be confused with The Heritage Foundation), but was changed to Historic Deerfield after Flynt's death in 1970.[3]

Local geography[]

Historic Deerfield is based on a 330-year-old, mile-long street situated along the Deerfield River in the Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts.

Deerfield history[]

At the time of European contact, the area now known as Deerfield was inhabited by the indigenous Pocumtuck nation. The town was originally established as a grant of land to the residents of Dedham, Massachusetts, who had given land to the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the purpose of settling Christianized Indians.

For much of the colonial period Deerfield was one of New England's frontier villages. Briefly abandoned during King Philip's War in the 1670s, it was subjected to French and Indian raids during King William's War in the 1690s. In Queen Anne's War the village was subjected to a major raid, in which 40 percent of the population was taken prisoner. French and allied Abenaki, Mohawk, and other warriors breached the palisade and raided the village. They killed numerous settlers and took more than 100 residents captive. Before leaving for Canada, the raiding party burned the village.

Almost all of those who survived the attack and the march to Canada eventually were ransomed and returned to New England. Eunice Williams, captured at age eight, was adopted by a Mohawk family and became totally assimilated. She married a Mohawk man and had a family with him, choosing not to return to New England. In 1741 she visited surviving siblings for the first time, and she made two more visits later.

Deerfield survived the raid, and the frontier was pushed farther north and west. Settlers eventually moved into present-day Vermont and established settlements farther up the Connecticut River in New Hampshire.

Art From Deerfield[]

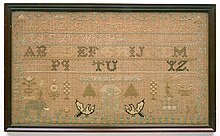

The town of Deerfield is home to a particular group of needlework samplers that share several defining features, known as the "White Dove" school. Popular in the area from 1790–1830, this style of sampler is named for the embroidered depiction of white doves outlined in black. Along with the doves, the style was typically characterized by an arrangement of baskets holding fruits and flowers, usually in a pyramid shape, sewn underneath an alphabet or verse, and surrounded by a three sided border.[4] The uniformity in the works created from 1798–1826 suggests that the girls who created them studied under one instructor, but who they were and where they taught is unknown.[5]

A well known example of the White Dove style was created by a girl named Esther Slate, at the age of ten years old in 1824. There are no less than three alphabets stitched into four separate rows, the first two alphabets are in a cursive font in both upper and lowercase letters, and the third alphabet is a block type font. The sampler is bordered by green vine motives on three sides, with a geometric triangle pattern on the bottom edge. Below the alphabets, Esther embroidered a garden scene, with a blue house in the center, flanked by two trees on either side, and a white picket fence surrounding them. Underneath the fence, the titular two white doves outlined in black stand with their wings spread. The picture is symmetrical up to the second tree on either side. On the left hand side, birds perch on sunflowers and crops, while an elephant and a monkey reside underneath. To the right, a fruit tree stands next to two of the popular white dove style fruit baskets.

Though the instructor who taught this style is unknown, the surviving pieces of the White Dove school were created by the children of prominent families in the area, and are in the collection of Historic Deerfield. Other examples of the style include the other sampler pictured on this page, made by Katy Bernard in 1793.

Collection database[]

Historic Deerfield's collections can be searched on the database maintained by the Five College Museums/Historic Deerfield.[6]

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Historic Deerfield. |

- Borden Base Line

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Franklin County, Massachusetts

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Massachusetts

References[]

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ Historic-deerfield.org

- ^ Greenfield, Brian (2009). Out of the attic : inventing antiques in twentieth-century New England. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 131–166. ISBN 978-1-55849-710-8.

- ^ Ring, Betty (1993). Girlhopd Embroidery: American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework 1650–1850. Alfred A. Knopf Inc.

- ^ Huber, Stephen (2011). With Needle and Brush : Schoolgirl Embroidery from the Connecticut River Valley, 1740–1840. Wesleyan University Press.

- ^ Museums.fivecolleges.edu

External links[]

- Historic Deerfield

- Town of Deerfield

- Old Deerfield Historic District - National Historic Landmarks Program

Coordinates: 42°32′49.2″N 72°36′14.9″W / 42.547000°N 72.604139°W

- Deerfield, Massachusetts

- Historic house museums in Massachusetts

- Open-air museums in Massachusetts

- History museums in Massachusetts

- Museums in Franklin County, Massachusetts

- Houses in Franklin County, Massachusetts

- National Historic Landmarks in Massachusetts

- National Register of Historic Places in Franklin County, Massachusetts

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Massachusetts