History of North Africa

North Africa is a relatively thin strip of land between the Sahara desert and the Mediterranean, stretching from Moroccan Atlantic coast to Egypt. Currently, the region comprises five countries, from west to east: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and Egypt.[1] The region has been influenced by many diverse cultures. The development of sea travel firmly brought the region into the Mediterranean world, especially during the classical period. In the 1st millennium AD, the Sahara became an equally important area for trade as camel caravans brought goods and people from the south. The region also has a small but crucial land link to the Middle East, and that area has also played a key role in the history of North Africa.

Prehistory[]

The earliest known humans lived in North Africa around 260,000 BC.[2] Through most of the Stone Age the climate in the region was very different from today, the Sahara being far more moist and savanna like. Home to herds of large mammals, this area could support a large hunter-gatherer population and the Aterian culture that developed was one of the most advanced paleolithic societies.

In the Mesolithic period, Capsian culture dominated the eastern part of North Africa with Neolithic farmers becoming predominant by 6000 BC. Over this period, the Sahara region was steadily drying, creating a barrier between North Africa and the rest of Africa.

Various populations of pastoralists have left paintings of abundant wildlife, domesticated animals, chariots, and a complex culture that dates back to at least 10,000 BCE in northern Niger and neighboring parts of southern Algeria and Libya. Several former northern Nigerien villages and archaeological sites date from the Green Sahara period of 7,500-7,000 to 3,500-3,000 BCE[citation needed]

The Nile Valley on the eastern edge of North Africa is one of the richest agricultural areas in the world. The desiccation of the Sahara is believed to have increased the population density in the Nile Valley and large cities developed. Eventually Ancient Egypt unified in one of the world's first civilizations.

Classical period[]

The expanse of the Libyan Desert cut Egypt off from the rest of North Africa. Egyptian boats, while well suited to the Nile, were not usable in the open Mediterranean. Moreover, the Egyptian merchant had far more prosperous destinations on Crete, Cyprus and the Levant.

Greeks from Europe and the Phoenicians from Asia also settled along the coast of Northern Africa. Both societies drew their prosperity from the sea and from ocean-born trade. They found only limited trading opportunities with the native inhabitants, and instead turned to colonization. The Greek trade was based mainly in the Aegean, Adriatic, Black, and Red Seas and they only established major cities in Cyrenaica, directly to the south of Greece. In 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt and for the next three centuries it was ruled by the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty.

The Phoenicians developed an even larger presence in North Africa with colonies from Tripoli to the Atlantic. One of the most important Phoenician cities was Carthage, which grew into one of the greatest powers in the region. At the height of its power, Carthage controlled the Western Mediterranean and most of North Africa outside of Egypt. However, Rome, Carthage's major rival to the north, defeated it in a series of wars known as the Punic Wars, resulting in Carthage's destruction in 146 BC and the annexation of its empire by the Romans. In 30 BC, Roman Emperor Octavian conquered Egypt, officially annexing it to the Empire and, for the first time, unifying the North African coast under a single ruler.

The Carthaginian power had penetrated deep into the Sahara ensuring the quiescence of the nomadic tribes in the region. The Roman Empire was more confined to the coast, yet routinely expropriated Berber land for Roman farmers. They thus faced a constant threat from the south. A network of forts and walls were established on the southern frontier, eventually securing the region well enough for local garrisons to control it without broader Imperial support.

When the Roman Empire began to collapse, North Africa was spared much of the disruption until the Vandal invasion of 429 AD. The Vandals ruled in North Africa until the territories were regained by Justinian of the Eastern Empire in the 6th century. Egypt was never invaded by the Vandals because there was a thousand-mile buffer of desert and because the Eastern Roman Empire was better defended.

During the rule of the Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Carthaginians and the Ottomans the Kabyle people managed to maintain their independence.[3][4][5][6] Still, after the Arab conquest of North Africa, the Kabyle people maintained the possession of their mountains.[7][8]

Arrival of Islam[]

The Arab Conquest[]

The Arab invasion of the Maghrib began in 642 CE when Amr ibn al-As, the governor of Egypt, invaded Cyrenaica, advancing as far as Tripoli by 645 CE. Further expansion into North Africa waited another twenty years, due to the First Fitna. In 670 CE, Uqba ibn Nafi al-Fihiri invaded what is now Tunisia in an attempt to take the region from the Byzantine Empire, but was only partially successful. He founded the town of Kairouan but was replaced by Abul-Muhajir Dinar in 674 CE. Abul-Muhajir successfully advanced into what is now eastern Algeria incorporating the Berber confederation ruled by Kusaila into the Islamic sphere of influence.[10]

In 681 CE Uqba was given command of the Arab forces again and advanced westward again in 682 CE, holding Kusaya as a hostage. He advanced to the Atlantic Ocean in the west and penetrated the Draa River Valley and the Sus region in what is now Morocco. However, Kusaila escaped during the campaign and attacked Uqba on his return and killed him near Biskra in what is now Algeria. After Uqba's death, the Arab armies retreated from Kairouan, which Kusaila took as his capital. He ruled there until he was defeated by an Arab army under . Zuhair himself was killed in 688 CE while fighting against the Byzantine Empire which had reoccupied Cyrenaica while he was busy in Tunisia.[10]

In 693 CE, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan sent an army of 40,000 men, commanded by Hasan ibn al-Nu'man, into Cyrenaica and Tripolitania to remove the Byzantine threat to the Umayyads advance in North Africa. They met no resistance until they reached Tunisia where they captured Carthage and defeated the Byzantines and Berbers around Bizerte.[10]

Soon afterwards, al-Nu'man's forces came into conflict with the indigenous Berbers of the Jrāwa tribe under the leadership of their queen, Al-Kahina. The Berbers defeated al-Nu'man in two engagements, the first on the river Nini and the second near , upon which al-Nu'man's forces retreated to Cyrenaica to wait for reinforcements. Reinforcements arrived in 697 CE and al-Nu'man advanced into what is now Tunisia, again meeting Al-Kahina near Gabis. This time he was successful and Al-Kahina retreated to Tubna where her forces were defeated and she was killed.[10]

al-Nu'man next recaptured Carthage from the Byzantines, who had retaken it when he retreated from Tunisia. He founded the city of Tunis nearby and used it as the base for the Ummayad navy in the Mediterranean Sea. The Byzantines were forced to abandon the Maghreb and retreat to the islands of the Mediterranean Sea. However, in 705 CE he was replaced by Musa bin Nusair, a protégé of then governor of Egypt, Abdul-Aziz ibn Marwan. Nusair attacked what is now Morocco, captured Tangier, and advanced to the river and the Tafilalt oasis in a three-year campaign.[10]

Kharijite Berber Rebellion[]

Rustamids[]

Banu Midrar[]

Aghlabids[]

Abbasids[]

Idrisids[]

Fatimids[]

The Muslim Berber Empires[]

Fatimids[]

The Fatimid Caliphate originated in Little Kabylia and was created by the Kutama Berbers after they conquered Ifriqiya.[11][12][13] The Fatimids were originally peasants from Kabylia, they managed to conquer all of North Africa in addition to some land in the Middle East and also had authority over Sicily.[14]

Zirids[]

The Zirids Dynasty was a family of Sanhaja Berbers that were originally from the Kabyle mountains.[15] During their reign they managed to rule over the entire Maghreb and also established their rule in parts of Al-Andalus. They also had suzerainty over the island of Sicily through the Kalbite Emirs and later assassinated the ruler and took over the Island.[16] When the Emirate of Sicily was split into separate taifas, Ayyub Ibn Tamim entered Sicily and united all of the taifas under his rule until he left the Island.

Hammadids[]

The Hammadids came to power after declaring their independence from the Zirids. They managed to conquer land in all of the Maghreb region, capturing and possessing significant territories such as: Algiers, Bougie, Tripoli, Sfax, Susa, Fez, Ouargla and Sijilmasa.[17][18][19] South of Tunisia, they also possessed a number of oasis that were the termini of trans-Saharan trade routes.[20]

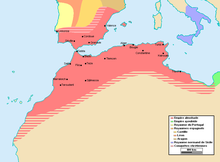

Almoravids[]

In the 11th century, Berbers of the Sahara began a jihad to reform Islam in North Africa and remove any trace of cultural or religious pluralism. This movement created an empire encompassing parts of Spain and North Africa. At its greatest extent, it appears to have included southern and eastern Iberia and roughly all of present-day Morocco. This movement seems to have assisted the southern penetration of Africa, one that was continued by later groups. In addition, the Almoravids are traditionally believed to have attacked and brought about the destruction of the West African Ghana Empire.[21]

However, this interpretation has been questioned. Conrad and Fisher (1982) argued that the notion of any Almoravid military conquest at its core is merely perpetuated folklore, derived from a misinterpretation or naive reliance on Arabic sources[22] while Dierke Lange agrees but argues that this doesn't preclude Almoravid political agitation, claiming that Ghana's demise owed much to the latter.[23]

Almohads[]

The Almohads (or Almohadis) were similar to the Almoravids, in that they similarly attacked any alternative beliefs that they saw as corruptions of Islam. They managed to conquer southern Spain, and their North African empire extended further than that of the Almoravids, reaching to Egypt.

Marinids[]

Hafsids[]

The Hafsids were a Masmuda-Berber dynasty ruling Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia) from 1229 to 1574. Their territories were stretched from east of modern Algeria to west of modern Libya during their zenith.

The dynasty was named after Muhammad bin Abu Hafs a Berber from the Masmuda tribe of Morocco. He was appointed governor of Ifriqiya (present day Tunisia) by Muhammad an-Nasir, Caliph of the Almohad empire between 1198 and 1213. The Banu Hafs, were a powerful group amongst the Almohads; their ancestor is Omar Abu Hafs al-Hentati, a member of the council of ten and a close companion of Ibn Tumart. His original name was "Fesga Oumzal", which later changed to "Abu Hafs Omar ibn Yahya al-Hentati" (also known as "Omar Inti") since it was a tradition of Ibn Tumart to rename his close companions once they had adhered to his religious teachings. The Hafsids as governors on behalf of the Almohads faced constant threats from Banu Ghaniya who were descendants of Almoravid princes which the Almohads had defeated and replaced as a ruling dynasty.

Hafsids were Ifriqiya governors of Almohads until 1229, when they declared independence. After the split of the Hafsids from the Almohads under Abu Zakariya (1229–1249), Abu Zakariya organised the administration in Ifriqiya (the Roman province of Africa in modern Maghreb; today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria and western Libya) and built Tunis up as the economic and cultural centre of the empire. At the same time, many Muslims from Al-Andalus fleeing the Spanish Reconquista of Castile, Aragon, and Portugal were absorbed. He also conquered Tlemcen in 1242 and took Abdalwadids as his vassal. His successor Muhammad I al-Mustansir (1249–1277) took the title of Caliph.

In the 14th century the empire underwent a temporary decline. Although the Hafsids succeeded for a time in subjugating the Kingdom of Tlemcen of the Abdalwadids, between 1347 and 1357 they were twice conquered by the Merinids of Morocco. The Abdalwadids however could not defeat the Bedouin; ultimately, the Hafsids were able to regain their empire. During the same period plague epidemics caused a considerable fall in population, further weakening the empire. Under the Hafsids, commerce with Christian Europe grew significantly, however piracy against Christian shipping grew as well, particularly during the rule of Abd al-Aziz II (1394–1434). The profits were used for a great building programme and to support art and culture. However, piracy also provoked retaliation from Aragon and Venice, which several times attacked Tunisian coastal cities. Under Utman (1435–1488) the Hafsids reached their zenith, as the caravan trade through the Sahara and with Egypt was developed, as well as sea trade with Venice and Aragon. The Bedouins and the cities of the empire became largely independent, leaving the Hafsids in control of only Tunis and Constantine.

In the 16th century the Hafsids became increasingly caught up in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire-supported Corsairs. Ottomans conquered Tunis in 1534 and held one year. Due to Ottoman threat, Hafsids were vassal of Spain after 1535. Ottomans again conquered Tunis in 1569 and held it for 4 years. Don Juan of Austria recaptured it in 1573. The latter conquered Tunis in 1574 and the Hafsids accepted becoming a Spanish vassal state to offset the Ottoman threat. Muhammad IV, the last Caliph of the Hafsids was brought to Constantinople and was subsequently executed due to his collaboration with Spain and the desire of the Ottoman Sultan to take the title of Caliph as he now controlled Mecca and Medina. The Hafsid lineage survived the Ottoman massacre by a branch of the family being taken to the Canary Island of Tenerife by the Spanish.

Zayyanids[]

Wattasids[]

Ottoman rule[]

After the Middle Ages, Northern Africa was loosely under the control of the Ottoman Empire, except for the Kabyle people and Moroccan region ruled by Saadi Sultanate.[24][25][26] Ottoman rule was centered on the cities of Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli.

European colonization[]

During the 18th and 19th century, North Africa was colonized by France, the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy. During the 1950s and 1960s, and into the 1970s, all of the North African states gained independence from their colonial European rulers, except for a few small Spanish colonies on the far northern tip of Morocco, and parts of the Sahara region, which went from Spanish to Moroccan rule.

In modern times the Suez canal in Egypt (constructed in 1869) has caused a great deal of controversy. The Convention of Constantinople in 1888 declared the canal a neutral zone under the protection of the British, after British troops had moved in to protect it in 1882. Under the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, the United Kingdom insisted on retaining control over the canal. In 1951 Egypt repudiated the treaty, and by 1954 Great Britain had agreed to pull out.

After the United Kingdom and the United States withdrew their pledge to support the construction of the Aswan Dam, President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the canal, which led Britain, France and Israel to invade in the week-long Suez War. As a result of damage and sunken ships, the canal was closed until April 1957, after it had been cleaned up with UN assistance. A United Nations force (UNEF) was established to maintain the neutrality of the canal and the Sinai Peninsula.

Historiographic and Conceptual Problems of North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa[]

Historiographic and Conceptual Problems[]

The current major problem in African studies that Mohamed (2010/2012)[27][28] identified is the inherited religious, Orientalist, colonial paradigm that European Africanists have preserved in present-day secularist, post-colonial, Anglophone African historiography.[27] African and African-American scholars also bear some responsibility in perpetuating this European Africanist preserved paradigm.[27]

Following conceptualizations of Africa developed by Leo Africanus and Hegel, European Africanists conceptually separated continental Africa into two racialized regions – Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa.[27] Sub-Saharan Africa, as a racist geographic construction, serves as an objectified, compartmentalized region of “Africa proper”, “Africa noire,” or “Black Africa.”[27] The African diaspora is also considered to be a part of the same racialized construction as Sub-Saharan Africa.[27] North Africa serves as a racialized region of “European Africa”, which is conceptually disconnected from Sub-Saharan Africa, and conceptually connected to the Middle East, Asia, and the Islamic world.[27]

As a result of these racialized constructions and the conceptual separation of Africa, darker skinned North Africans, such as the so-called Haratin, who have long resided in the Maghreb, and do not reside south of Saharan Africa, have become analogically alienated from their indigeneity and historic reality in North Africa.[27] While the origin of the term “Haratin” remains speculative, the term may not date much earlier than the 18th century CE and has been involuntarily assigned to darker skinned Maghrebians.[27] Prior to the modern use of the term Haratin as an identifier, and utilized in contrast to bidan or bayd (white), sumr/asmar, suud/aswad, or sudan/sudani (black/brown) were Arabic terms utilized as identifiers for darker skinned Maghrebians before the modern period.[27] “Haratin” is considered to be an offensive term by the darker skinned Maghrebians it is intended to identify; for example, people in the southern region (e.g., Wad Noun, Draa) of Morocco consider it to be an offensive term.[27] Despite its historicity and etymology being questionable, European colonialists and European Africanists have used the term Haratin as identifiers for groups of “black” and apparently “mixed” people found in Algeria, Mauritania, and Morocco.[27]

The Saadian invasion of the Songhai Empire serves as the precursor to later narratives that grouped darker skinned Maghrebians together and identified their origins as being Sub-Saharan West Africa.[28] With gold serving as a motivation behind the Saadian invasion of the Songhai Empire, this made way for changes in latter behaviors toward dark-skinned Africans.[28] As a result of changing behaviors toward dark-skinned Africans, darker skinned Maghrebians were forcibly recruited into the army of Ismail Ibn Sharif as the Black Guard, based on the claim of them having descended from enslaved peoples from the times of the Saadian invasion.[28] Shurafa historians of the modern period would later utilize these events in narratives about the manumission of enslaved “Hartani” (a vague term, which, by merit of it needing further definition, is implicit evidence for its historicity being questionable).[28] The narratives derived from Shurafa historians would later become analogically incorporated into the Americanized narratives (e.g., the trans-Saharan slave trade, imported enslaved Sub-Saharan West Africans, darker skinned Magrebian freedmen) of the present-day European Africanist paradigm.[28]

As opposed to having been developed through field research, the analogy in the present-day European Africanist paradigm, which conceptually alienates, dehistoricizes, and denaturalizes darker skinned North Africans in North Africa and darker skinned Africans throughout the Islamic world at-large, is primarily rooted in an Americanized textual tradition inherited from 19th century European Christian abolitionists.[27] Consequently, reliable history, as opposed to an antiquated analogy-based history, for darker skinned North Africans and darker skinned Africans in the Islamic world are limited.[27] Part of the textual tradition generally associates an inherited status of servant with dark skin (e.g., Negro labor, Negro cultivators, Negroid slaves, freedman).[27] The European Africanist paradigm uses this as the primary reference point for its construction of origins narratives for darker skinned North Africans (e.g., imported slaves from Sub-Saharan West Africa).[27] With darker skinned North Africans or darker skinned Africans in the Islamic world treated as an allegory of alterity, another part of the textual tradition is the trans-Saharan slave trade and their presence in these regions are treated as that of an African diaspora in North Africa and the Islamic world.[27] Altogether, darker skinned North Africans (e.g., “black” and apparently “mixed” Maghrebians), darker skinned Africans in the Islamic world, the inherited status of servant associated with dark skin, and the trans-Saharan slave trade are conflated and modeled in analogy with African-Americans and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.[27]

The trans-Saharan slave trade has been used as a literary device in narratives that analogically explain the origins of darker skinned North Africans in North Africa and the Islamic world.[27] Caravans have been equated with slave ships, and the amount of forcibly enslaved Africans transported across the Sahara are alleged to be numerically comparable to the considerably large amount of forcibly enslaved Africans transported across the Atlantic Ocean.[27] The simulated narrative of comparable numbers is contradicted by the limited presence of darker skinned North Africans in the present-day Maghreb.[27] As part of this simulated narrative, post-classical Egypt has also been characterized as having plantations.[27] Another part of this simulated narrative is an Orientalist construction of hypersexualized Moors, concubines, and eunuchs.[27] Concubines in harems have been used as an explanatory bridge between the allegation of comparable numbers of forcibly enslaved Africans and the limited amount of present-day darker skinned Maghrebians who have been characterized as their diasporic descendants.[27] Eunuchs were characterized as sentinels who guarded these harems.[28] The simulated narrative is also based on the major assumption that the indigenous peoples of the Maghreb were once purely white Berbers, who then became biracialized through miscegenation with black concubines[27] (existing within a geographic racial binary of pale-skinned Moors residing further north, closer to the Mediterranean region, and dark-skinned Moors residing further south, closer to the Sahara).[28] The religious polemical narrative involving the suffering of enslaved European Christians of the Barbary slave trade has also been adapted to fit the simulated narrative of a comparable number of enslaved Africans being transported by Muslim slaver caravans, from the south of Saharan Africa, into North Africa and the Islamic world.[27]

Despite being an inherited part of the 19th century religious polemical narratives, the use of race in the secularist narrative of the present-day European Africanist paradigm has given the paradigm an appearance of possessing scientific quality.[28] The religious polemical narrative (e.g., holy cause, hostile neologisms) of 19th century European abolitionists about Africa and Africans are silenced, but still preserved, in the secularist narratives of the present-day European Africanist paradigm.[27] The Orientalist stereotyped hypersexuality of the Moors were viewed by 19th century European abolitionists as deriving from the Quran.[28] The reference to times prior, often used in concert with biblical references, by 19th century European abolitionists, may indicate that realities described of Moors may have been literary fabrications.[28] The purpose of these apparent literary fabrications may have been to affirm their view of the Bible as being greater than the Quran and to affirm the viewpoints held by the readers of their composed works.[28] The adoption of 19th century European abolitionists’ religious polemical narrative into the present-day European Africanist paradigm may have been due to its correspondence with the established textual tradition.[28] The use of stereotyped hypersexuality for Moors are what 19th century European abolitionists and the present-day European Africanist paradigm have in common.[28]

Due to a lack of considerable development in field research regarding enslavement in Islamic societies, this has resulted in the present-day European Africanist paradigm relying on unreliable estimates for the trans-Saharan slave trade.[28] However, insufficient data has also used as a justification for continued use of the faulty present-day European Africanist paradigm.[28] Darker skinned Maghrebians, particularly in Morocco, have grown weary of the lack of discretion foreign academics have shown toward them, bear resentment toward the way they have been depicted by foreign academics, and consequently, find the intended activities of foreign academics to be predictable.[28] Rather than continuing to rely on the faulty present-day European Africanist paradigm, Mohamed (2012) recommends revising and improving the current Africanist paradigm (e.g., critical inspection of the origins and introduction of the present characterization of the Saharan caravan; reconsideration of what makes the trans-Saharan slave trade, within its own context in Africa, distinct from the trans-Atlantic slave trade; realistic consideration of the experiences of darker-skinned Maghrebians within their own regional context).[28]

Conceptual Problems[]

Merolla (2017)[29] has indicated that the academic study of Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa by Europeans developed with North Africa being conceptually subsumed within the Middle East and Arab world, whereas, the study of Sub-Saharan Africa was viewed as conceptually distinct from North Africa, and as its own region, viewed as inherently the same.[29] The common pattern of conceptual separation of continental Africa into two regions and the view of conceptual sameness within the region of Sub-Saharan Africa has continued until present-day.[29] Yet, with increasing exposure of this problem, discussion about the conceptual separation of Africa has begun to develop.[29]

The Sahara has served as a trans-regional zone for peoples in Africa.[29] Authors from various countries (e.g., Algeria, Cameroon, Sudan) in Africa have critiqued the conceptualization of the Sahara as a regional barrier, and provided counter-arguments supporting the interconnectedness of continental Africa; there are historic and cultural connections as well as trade between West Africa, North Africa, and East Africa (e.g., North Africa with Niger and Mali, North Africa with Tanzania and Sudan, major hubs of Islamic learning in Niger and Mali).[29] Africa has been conceptually compartmentalized into meaning “Black Africa”, “Africa South of the Sahara”, and “Sub-Saharan Africa.”[29] North Africa has been conceptually "Orientalized" and separated from Sub-Saharan Africa.[29] While its historic development has occurred within a longer time frame, the epistemic development (e.g., form, content) of the present-day racialized conceptual separation of Africa came as a result of the Berlin Conference and the Scramble for Africa.[29]

In African and Berber literary studies, scholarship has remained largely separate from one another.[29] The conceptual separation of Africa in these studies may be due to how editing policies of studies in the Anglophone and Francophone world are affected by the international politics of the Anglophone and Francophone world.[29] While studies in the Anglophone world have more clearly followed the trend of the conceptual separation of Africa, the Francophone world has been more nuanced, which may stem from imperial policies relating to French colonialism in North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa.[29] As the study of North Africa has largely been initiated by the Arabophone and Francophone world, denial of the Arabic language having become Africanized throughout the centuries it has been present in Africa has shown that the conceptual separation of Africa remains pervasive in the Francophone world; this denial may stem from historic development of the characterization of an Islamic Arabia existing as a diametric binary to Europe.[29] Among studies in the Francophone world, ties between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa have been denied or downplayed, while the ties (e.g., religious, cultural) between the regions and peoples (e.g., Arab language and literature with Berber language and literature) of the Middle East and North Africa have been established by diminishing the differences between the two and selectively focusing on the similarities between the two.[29] In the Francophone world, construction of racialized regions, such as Black Africa (Sub-Saharan Africans) and White Africa (North Africans, e.g., Berbers and Arabs), has also developed.[29]

Despite having invoked and utilized identities in reference to the racialized conceptualizations of Africa (e.g., North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa) to oppose imposed identities, Berbers have invoked North African identity to oppose Arabized and Islamicized identities, and Sub-Saharan Africans (e.g., Negritude, Black Consciousness) and the African diaspora (e.g., Black is Beautiful) have invoked and utilized black identity to oppose colonialism and racism.[29] While Berber studies has largely sought to be establish ties between Berbers and North Africa with Arabs and the Middle East, Merolla (2017) indicated that efforts to establish ties between Berbers and North Africa with Sub-Saharan Africans and Sub-Saharan Africa have recently started to being undertaken.[29]

Military history of Northern Africa[]

Genetic history of North Africa[]

Archaic Human DNA[]

While Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in non-Africans outside of Africa are more certain, archaic human ancestry in Africans is less certain and is too early to be established with certainty.[30]

Ancient DNA[]

Egypt[]

Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamen carried haplogroup R1b.[31] Thuya, Tiye, Tutankhamen’s mother, and Tutankhamen carried haplogroup K.[31]

Ramesses III and Unknown Man E, possibly Pentawere, carried haplogroup E1b1a.[31][32][33]

Khnum-aa, Khnum-Nakht, and Nakht-Ankh carried haplogroup M1a1.[31]

Libya[]

At Takarkori rockshelter, in Libya, two naturally mummified women, dated to the Middle Pastoral Period (7000 BP), carried basal haplogroup N.[34]

Morocco[]

The Taforalts of Morocco, who were found to be 63.5% Natufian, were also found to be 36.5% Sub-Saharan African (e.g., Hadza), which is drawn out, most of all, by West Africans (e.g., Yoruba, Mende).[35] In addition to having similarity with the remnant of a more basal Sub-Saharan African lineage (e.g., a basal West African lineage shared between Yoruba and Mende peoples), the Sub-Saharan African DNA in the Taforalt people of the Iberomaurusian culture may be best represented by modern West Africans (e.g., Yoruba).[36]

Y-Chromosomal DNA[]

Mitochondrial DNA[]

Mitochondrial haplogroups L3, M, and N are found among Sudanese peoples (e.g., Beja, Nilotics, Nuba, Nubians), who have no known interaction (e.g., history of migration/admixture) with Europeans or Asians; rather than having developed in a post-Out-of-Africa migration context, mitochondrial macrohaplogroup L3/M/N and its subsequent development into distinct mitochondrial haplogroups (e.g., Haplogroup L3, Haplogroup M, Haplogroup N) may have occurred in East Africa at a time that considerably predates the Out-of-Africa migration event of 50,000 BP.[37]

Autosomal DNA[]

Medical DNA[]

Lactase Persistence[]

Neolithic agriculturalists, who may have resided in Northeast Africa and the Near East, may have been the source population for lactase persistence variants, including –13910*T, and may have been subsequently supplanted by later migrations of peoples.[38] The Sub-Saharan West African Fulani, the North African Tuareg, and European agriculturalists, who are descendants of these Neolithic agriculturalists, share the lactase persistence variant –13910*T.[38] While shared by Fulani and Tuareg herders, compared to the Tuareg variant, the Fulani variant of –13910*T has undergone a longer period of haplotype differentiation.[38] The Fulani lactase persistence variant –13910*T may have spread, along with cattle pastoralism, between 9686 BP and 7534 BP, possibly around 8500 BP; corroborating this timeframe for the Fulani, by at least 7500 BP, there is evidence of herders engaging in the act of milking in the Central Sahara.[38]

List of archaeological cultures and sites[]

|

|

|

|

|

|

See also[]

- Genetic history of North Africa

- History of Africa#North Africa

- History of Algeria

- History of Egypt

- History of Libya

- History of Morocco

- History of Tunisia

- History of Western Sahara

References[]

- ^ According to UN country classification. Western Sahara (formerly Spanish Sahara) is disputed mostly administered by Morocco. The Polisario Front claims the territory in militating for the establishment of an independent republic, and exercises limited control over rump border territories.

- ^ Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah E.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano (2017-06-07). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. doi:10.1038/nature22336. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28593953.

- ^ The Middle East and North Africa: Pg 156

- ^ Sketches of Algeria During the Kabyle War By Hugh Mulleneux Walmsley: Pg 118

- ^ The Kabyle People By Glora M. Wysner

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 1: Pg 568

- ^ The art journal London, Volume 4: Pg 45

- ^ The Barbary Coast By Henry Martyn Field: Pg 93

- ^ Hans Kung, Tracing the Way : Spiritual Dimensions of the World Religions, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006, page 248

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period, Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- ^ African Foreign Policy and Diplomacy from Antiquity to the 21st Century, Volume 1: Pg 92

- ^ An Atlas of African History by J. D. Fage: Pg 11

- ^ An Atlas of African History - J. D. Fage

- ^ Ibn Khaldun: The Birth of History and the Past of the Third World: Pg 67

- ^ A History of Africa - J.D. Fage: Pg 166

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3 - J.D. Fage: Pg 16

- ^ Saladin, the Almohads and the Banū Ghāniya: The Contest for North Africa: Pg 42

- ^ Islam: Art and Architecture: Pg 614

- ^ Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen): Pg 55 & 56

- ^ Nomads and Crusaders, A.D. 1000-1368 By Archibald Ross Lewis

- ^ Lange, Dierk (1996). "The Almoravid expansion and the downfall of Ghana", Der Islam 73, pp. 122-159

- ^ Masonen & Fisher 1996.

- ^ Lange 1996, pp. 122-159.

- ^ Sketches of Algeria During the Kabyle War By Hugh Mulleneux Walmsley: Pg 118

- ^ [Morocco]https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=lsVvCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT219#v=onepage&q&f=true Memoirs Of Marshal Bugeaud From His Private Correspondence And Original Documents, 1784-1849 Maréchal Thomas Robert Bugeaud duc d’Isly]

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islamedited by John L. Esposito: Pg 165

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Mohamed, Mohamed Hassan. "Africanists and Africans of the Maghrib: casualties of Analogy". Taylor & Francis Online. The Journal of North African Studies.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mohamed, Mohamed Hassan. "Africanists and Africans of the Maghrib II: casualties of secularity". Taylor & Francis Online. The Journal of North African Studies.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Merolla, Daniela. "Beyond 'two Africas' in African and Berber literary studies". Scholarly Publications Leiden University. African Studies Centre Leiden.

- ^ Bergström, Anders; et al. "Origins of modern human ancestry" (PDF). Nature.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gad, Yehia Z; et al. "Insights from ancient DNA analysis of Egyptian human mummies: clues to disease and kinship". Oxford Academic. Human Molecular Genetics.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi. "Revisiting the harem conspiracy and death of Ramesses III: anthropological, forensic, radiological, and genetic study". ResearchGate. BMJ.

- ^ Gourdine, Jean-Philippe; Keita, Shomarka; Gourdine, Jean-Luc; Anselin, Alain. "Ancient Egyptian Genomes from northern Egypt: Further discussion". ResearchGate. Nature Communications.

- ^ Vai, Stefania; et al. "Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic 'green' Sahara". Springer Nature. Scientific Reports.

- ^ Van De Loosdrecht, Marieke; et al. "Pleistocene North African genomes link Near Eastern and sub-Saharan African human populations". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Science.

- ^ Jeong, Choongwon. "Current Trends in Ancient DNA Study". SpringerLink. The Handbook of Mummy Studies.

- ^ Osman, Maha M.; et al. "Mitochondrial HVRI and whole mitogenome sequence variations portray similar scenarios on the genetic structure and ancestry of northeast Africans" (PDF). Institute of Endemic Diseases. Meta Gene.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Priehodová, Edita; et al. "Sahelian pastoralism from the perspective of variantsassociated with lactase persistence" (PDF). HAL Archives. American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

Further reading[]

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33184-5.

- Cesari, Jocelyne. The awakening of Muslim democracy: Religion, modernity, and the state (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- Falola, Toyin, Jason Morgan, and Bukola Adeyemi Oyeniyi. Culture and customs of Libya (Abc-clio, 2012).

- Fischbach, ed. Michael R. Biographical encyclopedia of the modern Middle East and North Africa (Gale Group, 2008).

- Ilahiane, Hsain. Historical dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen) (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

- Issawi, Charles. An economic history of the Middle East and North Africa (Routledge, 2013).

- Naylor, Phillip C. North Africa, Revised Edition: A History from Antiquity to the Present (University of Texas Press, 2015).

- Stearns, Peter N., et al. World Civilizations: The Global Experience (AP Edition DBQ Update. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2006) p. 174.

External links[]

- History of North Africa

- Maghreb

- History of the Mediterranean