House of Games

| House of Games | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | David Mamet |

| Screenplay by | David Mamet |

| Story by | Jonathan Katz & David Mamet |

| Produced by | Michael Hausman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Juan Ruiz Anchía |

| Edited by | Trudy Ship |

| Music by | Alaric Jans |

Production company | Filmhaus |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date | October 11, 1987 |

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2.6 million[1] |

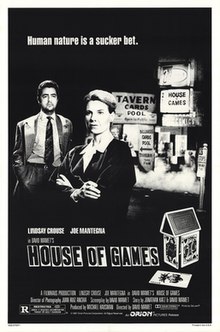

House of Games is a 1987 American neo-noir[2] heist-thriller film directed by David Mamet, his directorial debut. He also wrote the screenplay, based on a story he co-wrote with Jonathan Katz. The film's cast includes Lindsay Crouse, Joe Mantegna, Ricky Jay, and J. T. Walsh.

Plot[]

Margaret Ford is a psychiatrist who has achieved success with her recently published book about OCD, but who feels unfulfilled. During a session one day, patient Billy Hahn informs her that his life is in danger because he owes money to a criminal figure named Mike Mancuso and brandishes a gun, threatening to kill himself. Margaret persuades him to surrender the weapon to her and promises that she will help.

That night, Margaret visits a pool hall owned by Mike and confronts him. Mike says that he is willing to forgive Billy's debt if Margaret accompanies him to a back room poker game and identifies the tell of George, another player. She agrees, and spots George playing with his ring when he bluffs. She discloses this to Mike, who calls the bluff. However, George wins the hand and demands that Mike pay the $6,000 bet, which he is unable to do. George pulls a gun but Margaret intervenes and offers to pay the debt with a personal check. She then notices that the gun is a water pistol, and realizes that the entire game is a set-up to trick her out of her money. She declines to pay the bet, and spends the rest of the night socializing with the con men. The experience has excited her, however, and she returns the next night to request that Mike teach her about cons so that she can write a book about the experience. Mike appears skeptical, but agrees.

Mike begins to enchant Margaret by showing her several simple tricks. Eventually, the two steal a hotel room and have sex. While in the room, he instructs her that all con artists take a small token from every "mark" to signify their dominance. While Mike is in the bathroom, she takes a small pocket knife from the table, believing that it belongs to the man who rented the room. Afterwards, Mike says that he is late for another, large con with his associates at the same hotel. Margaret is eager to tag along and, reluctantly, Mike allows it. The con involves Mike, his partner Joey and the "mark", a businessman discovering a briefcase full of money, and taking it to a hotel room. There they will discuss whether to turn it in or split it among themselves. In the hotel room, Margaret discovers that the businessman is actually an undercover policeman, and the trick is a sting operation. She tells Mike and they attempt to escape, but the policeman blocks their way and tries to arrest them. There is a struggle that ends with Margaret accidentally causing the policeman to fatally shoot himself. The three leave via the stairwell and end up in the garage, where they force Margaret to steal a car, driving past two uniformed police officers with the con men concealed in the back seat. While abandoning the car, they realize that the briefcase, containing $80,000 borrowed from the Mafia for the con, has been lost. Margaret finally offers to give Mike $80,000 of her own money so he can pay back the mob.

Mike tells Margaret that they must split up so as not to draw any attention from the police, and says that he is flying away to hide. Margaret is riddled with guilt but, by chance, spots Billy driving the same red convertible she had been forced to steal earlier. She tracks him to a bar, where she spies on Mike and the entire group, including the man whose hotel room they stole, and the undercover policeman, discussing how the preceding events were a scheme to con her out of $80,000. She also learns that the pocket knife she stole from the hotel room belongs to Mike.

After overhearing that Mike is flying to Las Vegas that night, Margaret waits for him at the airport. She says that she's been so worried about the police that she has withdrawn her entire life savings, and pleads to start a new life with him. They go to a restricted and deserted baggage handling area where Mike realizes he's being tricked when she lets it slip that she stole his pocket knife, something she wouldn't have known if she hadn't overheard their discussion of the con. He says that he cannot return her money because it has already been divided. Margaret, however, produces Billy's gun and demands that he beg for his life. Mike refuses, thinking that he is calling her bluff, but Margaret shoots him in the leg. When Mike curses her, she shoots him five more times, killing him. She calmly conceals the gun and walks away.

Later, Margaret is shown just returned from a vacation, having moved on from the ordeal. While talking with a colleague at a restaurant, she seems to show no remorse for killing Mike stating, "When you've done something unforgivable, you must forgive yourself; and that's what I've done and it's done." After her friend leaves the table, Margaret distracts another diner so as to steal a gold lighter from her purse, relishing the brief thrill.

Cast[]

- Lindsay Crouse as Dr. Margaret Ford

- Joe Mantegna as Mike Mancuso

- Steven Goldstein as Billy Hahn

- Ricky Jay as George

- Mike Nussbaum as Joey

- J. T. Walsh as the Businessman

- Lilia Skala as Dr. Littauer

- William H. Macy as Sgt. Moran

Reception[]

Describing the structure of the film as "diabolical and impeccable", Roger Ebert gave the film his highest rating: 4 stars. "This movie is awake. I have seen so many films that were sleepwalking through the debris of old plots and second-hand ideas that it was a constant pleasure to watch House of Games."[3] Ebert later included the film in his list of Great Movies.[4] Calling the film "a wonderfully devious comedy", Vincent Canby also gave it a thumbs up. "Mr. Mamet, poker player and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, makes a fine, completely self-assured debut directing his original screenplay. Sometimes he's bluffing outrageously, but that's all right too."[5] Striking a contrary note, The Washington Post saw Mamet as "rechewing film noir, Hitchcock twists and MacGuffins, as well as the Freudian mumbo-jumbo already masticated tasteless by so many cine-kids."[6] It holds a 96% fresh rating at Rotten Tomatoes.[7] Dialogue from the film was sampled by the British pop group Saint Etienne on their first album Foxbase Alpha on the track "Etienne Gonna Die".

Home media[]

In August 2007, the Criterion Collection released a special edition of Mamet's film on DVD. Among the supplemental material included are an audio commentary with Mamet and Ricky Jay, new interviews with actors Lindsay Crouse and Joe Mantegna, and a short documentary shot on location during the film's production.[8]

Stage adaptation[]

Playwright Richard Bean adapted Mamet's script for a production at the Almeida Theatre, London, in September 2010. To meet the confines of the medium the stage version is set in just two locations, and the final resolution between Mike and Margaret is softened. Critical reaction to Bean's version was mixed: Michael Billington found only a "pointless exercise", but Charles Spencer thought that the stage version delivered "far better value than the original picture".[9][10]

References[]

- ^ "Box office / business for House of Games (1987)". IMDb. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth; eds. (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd ed.). Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 16, 1987). "House of Games". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 31, 1999). "Great Movie – House of Games". Roger Ebert. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (October 11, 1987). "Mamet Makes A Debut With 'House Of Games'". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ^ Howe, Desson (December 18, 1987). "House of Games". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ^ "House of Games (1987)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ^ The Criterion Collection: House of Games by David Mamet

- ^ Billington, Michael (September 17, 2010). "House of Games". The Guardian. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ^ Spencer, Charles (September 17, 2010). "House of Games, Almeida Theatre". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

External links[]

- House of Games at IMDb

- House of Games at AllMovie

- House of Games at Rotten Tomatoes

- House of Games at Box Office Mojo

- House of Games at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Roger Ebert's "Great Movies – House of Games"

- House of Games: On Your Mark an essay by Kent Jones at the Criterion Collection

- English-language films

- 1987 films

- 1987 directorial debut films

- 1980s crime thriller films

- 1980s heist films

- American crime thriller films

- American films

- American heist films

- American neo-noir films

- Films about con artists

- Films about physicians

- Films about writers

- Films adapted into plays

- Films directed by David Mamet

- Films set in Seattle

- Films with screenplays by David Mamet

- Gambling films

- Plays by Richard Bean