How I Won the War

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (July 2012) |

| How I Won the War | |

|---|---|

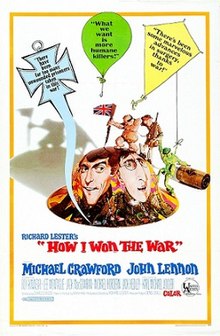

US film poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Lester |

| Screenplay by | Charles Wood |

| Based on | How I Won the War by Patrick Ryan |

| Produced by | Richard Lester |

| Starring | Michael Crawford John Lennon Roy Kinnear Lee Montague Jack MacGowran Michael Hordern Jack Hedley Karl Michael Vogler |

| Cinematography | David Watkin |

| Edited by | John Victor-Smith |

| Music by | Ken Thorne |

Production company | Petersham Pictures |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | 18 October 1967 (UK) 23 October 1967 (US) |

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

How I Won the War is a 1967 British black comedy film directed and produced by Richard Lester, based on the 1963 novel of the same name by Patrick Ryan. The film stars Michael Crawford as bungling British Army Officer Lieutenant Earnest Goodbody, with John Lennon of The Beatles (in his only non-musical role, as Musketeer Gripweed), Jack MacGowran (Musketeer Juniper), Roy Kinnear (Musketeer Clapper) and Lee Montague (Sergeant, although referred to by the equivalent, albeit fictional rank of "Corporal of Musket" Transom) as soldiers under his command.

The film uses an inconsistent variety of styles—vignette, straight-to-camera, and, extensively, parody of the war film genre, docu-drama, and popular war literature—to tell the story of 3rd Troop, the 4th Musketeers (a fictional regiment reminiscent of the Royal Fusiliers and the Household Cavalry) and their misadventures in the Second World War. This is told in the comic/absurdist vein throughout, a central plot being the setting-up of an "Advanced Area Cricket Pitch" behind enemy lines in North Africa, but it is all broadly based on the Western Desert Campaign in mid-late 1942[1] and the crossing of the last intact bridge on the Rhine at Remagen in early 1945. The film was not critically well received.

Plot[]

Lieutenant Goodbody is an inept, idealistic, naïve, and almost relentlessly jingoistic wartime-commissioned (not regular) officer. One of the main subversive themes in the film is the platoon's repeated attempts or temptations to kill or otherwise rid themselves of their complete liability of a commander. While Goodbody's ineptitude and attempts at derring-do lead to the gradual demise of the unit, he survives, together with the unit's persistent deserter and another of his charges who become confined to psychiatric care. Every time a character is killed, he is replaced by an actor in bright red, blue, or green-coloured World War II uniform, whose face is also coloured and obscured so that he appears to be a living toy soldier. This reinforces Goodbody's repeated comparisons of war to playing a game.

Cast[]

- Michael Crawford as Lieutenant Earnest Goodbody

- John Lennon as Gripweed

- Roy Kinnear as Clapper

- Lee Montague as Sergeant/Corporal of Musket Transom

- Jack MacGowran as Juniper

- Michael Hordern as Grapple

- Jack Hedley as Melancholy Musketeer

- Karl Michael Vogler as Odlebog

- Ronald Lacey as Spool

- James Cossins as Drogue

- Ewan Hooper as Dooley

- Alexander Knox as American General Omar Bradley

- Robert Hardy as British General

- Sheila Hancock as Mrs. Clapper's Friend

- as Flappy-Trousered Man

- as Paratrooper

- Paul Daneman as Skipper

- Peter Graves as Staff Officer

- Jack May as Toby

- Richard Pearson as Old Man at Alamein

- as Woman in Desert

- John Ronane as Operator

- Norman Chappell as Soldier at Alamein

- Bryan Pringle as Reporter

- Fanny Carby as Mrs. Clapper

- Dandy Nichols as 1st Old Lady

- Gretchen Franklin as 2nd Old Lady

- John Junkin as Large Child

- as Driver

- as 1st Replacement

- Kenneth Colley as 2nd Replacement

Production[]

Filming took place during the autumn of 1966 in the German state of Lower Saxony, at the Bergen-Hohne Training Area, Verden an der Aller and Achim, as well as the Province of Almería in Spain.[2] Lennon, taking a break from the Beatles, was asked by Lester to play Musketeer Gripweed. To prepare for the role, Lennon got a haircut, contrasting sharply with his mop-top image. During filming, he started wearing round "granny" glasses (the same type of glasses worn by the film's screenwriter, Charles Wood); the glasses would become iconic as the nearsighted Lennon would mainly wear this particular style of glasses for the rest of his life. A photo of Lennon in character as Gripweed found its way into many print publications, including the front page of the first issue of Rolling Stone, released in November 1967.

During his stay in Almería, Lennon had rented a villa called Santa Isabel that he and wife Cynthia Lennon shared with both his co-star Michael Crawford and his then wife, Gabrielle Lewis, whose wrought-iron gates and surrounding lush vegetation bore a resemblance to Strawberry Field, a Salvation Army garden near Lennon's childhood home; it was this observation that inspired Lennon to write "Strawberry Fields Forever" while filming.[3] The villa was later turned into the House of Cinema, a museum dedicated to the history of movie production in Almería province.[4]

The Spanish film Living Is Easy with Eyes Closed (2013) revolves around the filming in Almería.

From 28 to 29 December 1966, Lennon recorded all post-synchronisation work for his character at Twickenham Film Studios in London, England.

The film's release was delayed by six months as Richard Lester went on to work on Petulia (1968) shortly after completing How I Won the War.

Narrative and themes[]

In writing the script, the author, Charles Wood, borrowed themes and dialogue from his surreal and bitterly dark (and banned) anti-war play Dingo. In particular the character of the spectral clown 'Juniper' is closely modelled on the Camp Comic from the play, who likewise uses a blackly comic style to ridicule the fatuous glorification of war. Goodbody narrates the film retrospectively, more or less, while in conversation with his German officer captor, 'Odlebog', at the Rhine bridgehead in 1945. From their duologue emerges another key source of subversion – the two officers are in fact united in their class attitudes and officer-status contempt for (and ignorance of) their men. While they admit that the question of the massacre of Jews might divide them, they equally admit that it is not of prime concern to either of them. Goodbody's jingoistic patriotism finally relents when he accepts his German counterpart's accusation of being, in principle, a Fascist. They then resolve to settle their disagreements on a commercial basis (Odlebog proposes selling Goodbody the last intact bridge over the Rhine; in the novel the bridge is identified as that at Remagen) which could be construed as a satire on unethical business practices and capitalism. This sequence also appears in the novel. Fascism amongst the British is previously mentioned when Gripweed (Lennon's character) is revealed to be a former follower of Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists, though Colonel Grapple (played by Michael Hordern) sees nothing for Gripweed to be embarrassed about, stressing that "Fascism is something you grow out of". One monologue in the film concerns Musketeer Juniper's lament – while impersonating a high-ranked officer – about how officer material is drawn from the working and lower class, and not (as it used to be) from the feudal aristocracy.

The Regiment[]

In the novel, Patrick Ryan chose not to identify a real Army unit. The officers chase wine and glory, the soldiers chase sex and evade the enemy. The model is a regular infantry regiment forced, in wartime, to accept temporarily commissioned officers like Goodbody into its number, as well as returning reservists called back into service. In both world wars this has provided a huge bone of contention for regular regiments, where the exclusive esprit de corps is highly valued and safeguarded. The name Musketeers recalls the Royal Fusiliers, but the later mention of the "Brigade of Musketeers" recalls the Brigade of Guards. In the film, the regiment is presented as a cavalry regiment (armoured with tanks or light armour, such as the half-tracks) that has been adapted to "an independent role as infantry". The platoon of the novel has become a troop, a Cavalry designation. None of these features come from the novel, such as the use of half-tracks and Transom's appointment as "Corporal of Musket", which suggests the cavalry title Corporal of Horse. These aspects are most likely due to the screenwriter Charles Wood being a former regular army cavalryman.

Comparison with the novel[]

The novel uses none of the absurdist/surrealist devices associated with the film and differs greatly in style and content. The novel represents a far more conservative, structured (though still comic) war memoir, told by a sarcastically naïve and puerile Lieutenant Goodbody in the first person. It follows an authentic chronology of the war consistent with one of the long-serving regular infantry units – for example of the 4th Infantry Division – such as the 2nd Royal Fusiliers, including (unlike the film) the campaigns in Italy and Greece. Rather than surrealism the novel offers some quite chillingly vivid accounts of Tunis and Cassino. Patrick Ryan served as an infantry and then a reconnaissance officer in the war. Throughout, the author's bitterness at the pointlessness of war, and the battle of class interests in the hierarchy, are common to the film, as are most of the characters (though the novel predictably includes many more than the film).

Comparison with Candide[]

It has been pointed out, including by Leslie Halliwell, that there are echoes of Voltaire's Candide in the story, especially in the continual, improbable, inexplicable reappearance of Colonel Grapple.[citation needed] Grapple is supposed to be Lieutenant Goodbody's old (OCTU) Training Officer, full of ruthless, old-school British Empire optimism (rather than the Leibnizian optimism of Candide's Pangloss).[citation needed] Another frequently reappearing feature is Musketeer Clapper's endless series of hopeless personal problems, invariably involving his wife's infidelities. Only the second of these recurring scenes is found in the novel, and in this case, unlike Candide, the optimism always comes from the innocent Goodbody (Candide), never Clapper.

Reception[]

The film holds a "rotten" 54% rating at the film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, receiving 6 negative reviews out of 13.[5] In his review for the film, Roger Ebert gave the movie two stars, describing it as "not a brave or outspoken film".[6] John Simon called it "pretentious tomfoolery" and Monthly Film Bulletin felt "that Lester has bitten off more than he can chew".[7]

Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic described How I Won the War as 'the most ruthless mockery of the killer instinct and of patriotism that has ever reached the screen'.[8]

References[]

- ^ Robert Hardy, 16:23-16:29 (DVD version)

- ^ Comp. Blazek, Matthias: Vor 50 Jahren startete im Celler Raum der Beat durch – 50 Jahre Beatlemania in Celle, bpr-Projekt GbR, Celle 2013, ISBN 978-3-00-041877-8, p. 5–6.

- ^ Aftab, Kaleem (18 October 2013). "Living is Easy With Eyes Closed: How John Lennon's Role in a 1960s War Film Inspired a Whole New Movie". The Independent. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Casa del Cine | City of Almeria, Andalucia, Southern Spain". 13 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "How I Won the War".

- ^ Ebert, Roger (7 January 1968). "How I Won the War". Chicago Sun Times.

- ^ Walker, John (1993). Halliwell's Film Guide (9th ed.). p. 574. ISBN 0-00-255-349-X.

- ^ Kauffmann, Stanley (1979). Before My Eyes Film Criticism & Comment. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 14.

External links[]

- English-language films

- British films

- 1967 films

- British satirical films

- British political satire films

- British black comedy films

- World War II films

- Military humor in film

- 1960s black comedy films

- Anti-war films

- British avant-garde and experimental films

- Films directed by Richard Lester

- Films set in 1939

- Films set in 1942

- Films set in 1945

- Films set in Germany

- Films shot in Almería

- Films shot in Germany

- 1960s political films

- 1960s war films

- Films based on British novels

- 1967 comedy films

- 1967 drama films

- North African campaign films

- Western Front of World War II films