The Three Musketeers (1973 live-action film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2010) |

| The Three Musketeers | |

|---|---|

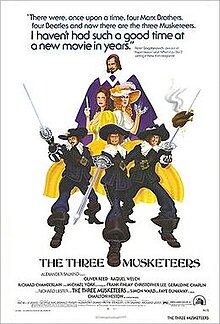

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Lester[1] |

| Written by | George MacDonald Fraser |

| Based on | The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas père |

| Produced by | Ilya Salkind[2] |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | David Watkin |

| Edited by | John Victor Smith |

| Music by | Michel Legrand |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4.5 million[3] |

| Box office | $10.1 million (rentals)[4] |

The Three Musketeers (also known as The Three Musketeers (The Queen's Diamonds)) is a 1973 film based on the 1844 novel The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas. It was directed by Richard Lester and written by George MacDonald Fraser. It was originally proposed in the 1960s as a vehicle for The Beatles, whom Lester had directed in two other films.

The film adheres closely to the novel, and also injects a fair amount of humor. It was shot by David Watkin, with an eye for period detail. The fight scenes were choreographed by master swordsman William Hobbs.

Plot[]

Having learned swordsmanship from his father, the young country bumpkin d'Artagnan arrives in Paris with dreams of becoming a king's musketeer. Unaccustomed to the city life, he makes a number of clumsy faux pas. First he finds himself insulted, knocked out and robbed by the Comte de Rochefort, an agent of Cardinal Richelieu, and once in Paris comes into conflict with three musketeers, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis, each of whom challenges him to a duel for some accidental insult or embarrassment. As the first of these duels is about to begin, Jussac arrives with five additional swordsmen of Cardinal Richelieu's guards. D'Artagnan sides with the musketeers in the ensuing street fight and becomes their ally in opposition to the Cardinal, who wishes to increase his already considerable power over the king, Louis XIII. D'Artagnan also begins an affair with his landlord's wife, Constance Bonacieux, who is dressmaker to the Queen, Anne of Austria.

Meanwhile, the Duke of Buckingham, former lover of the Queen, turns up and asks for something in remembrance of her; she gives him a necklace with twelve settings of diamonds, a gift from her husband. From the Queen's treacherous lady-in-waiting, the Cardinal learns of the rendezvous and suggests to the none-too-bright King to throw a ball in his wife's honor, and request she wear the diamonds he gave her. The Cardinal also sends his agent Milady de Winter to England, who seduces the Duke and steals two of the necklace's diamonds.

Meanwhile, the Queen has confided her troubles in Constance, who asks d'Artagnan to ride to England and get back the diamonds. D'Artagnan and the three musketeers set out, but on the way the Cardinal's men attack them. Only d'Artagnan and his servant make it through to Buckingham, where they discover the loss of two of the diamond settings. The Duke replaces the two settings, and d'Artagnan races back to Paris. Porthos, Athos, and Aramis, wounded but not dead as d'Artagnan had feared, aid the delivery of the complete necklace to the Queen, saving the royal couple from the embarrassment which the Cardinal had plotted.

Captain Tréville eventually inducts d'Artagnan into the Musketeers of the King's Guard.

Cast[]

- Michael York as d'Artagnan

- Oliver Reed as Athos

- Frank Finlay as Porthos / O'Reilly

- Richard Chamberlain as Aramis

- Jean-Pierre Cassel as King Louis XIII of France

- Geraldine Chaplin as Anne of Austria

- Charlton Heston as Cardinal Richelieu

- Faye Dunaway as Milady de Winter

- Christopher Lee as the Count De Rochefort

- Simon Ward as the Duke of Buckingham

- Raquel Welch as Constance Bonacieux

- Spike Milligan as M. Bonacieux

- Roy Kinnear as Planchet

- Sybil Danning as Eugenie

- Nicole Calfan as Kitty

Production[]

Development[]

According to George MacDonald Fraser, Richard Lester became involved with the project when the producers briefly considered casting The Beatles as the Musketeers, as Lester had directed two films with the group. The Beatles idea fell by the wayside but Lester stayed.[5] It would be Lester's first film in five years, although he had been busy directing commercials and had sought finance for other projects in that time, including an adaptation of the novel Flashman by George MacDonald Fraser.[3]

Lester says he had "never heard of" the Salkinds. They asked him if he was interested in doing The Three Musketeers and asked if he had read it. Lester said "Yes, I have read it, everybody's read it". He read "the first 200 pages, got excited and said yes".[3]

Lester said the producers "wanted it to be a sexy film and they wanted it to be with big sexy stars" such as Leonard Whiting and Ursula Andress. He said "I just didn't say no to anything in the early stages" and that the "die was cast" when he was allowed to hire George MacDonald Fraser to write the script.[6]

Fraser had never written a script before but thought that Flashman had the tone he was going for. In late 1972 Lester offered Fraser the job.[7] According to Fraser, Lester originally said he wanted to make a four-hour film and cast Richard Chamberlain as Aramis. It was later decided to turn the script into two films.[5] Fraser says he wrote them as two films, but no one told the actors.[8]

Lester says Fraser wrote the scripts in five weeks and they were "perfect... just wonderful."[7] "It's the journalism training," said Fraser.[8]

Casting[]

Lester says the Salkinds left him alone creatively for most of the film apart from insisting that Raquel Welch and Simon Ward be cast.[9] "Raquel is very big in all the small countries," said Ilya Salkind.[3]

"I did the picture because of Dick Lester," said Charlton Heston.[3]

In August 1973 Welch withdrew from the film due to creative and artistic differences. She announced she would instead make a film ''Decline and Fall of a Very Nice Lady.[10] However Welch wound up rejoining the film.

Filming[]

The film was originally meant to be shot in Hungary. However after visiting the country Lester felt this would not be feasible, in part because of restrictions of the government on filming.[11]

The movie ended up being shot in Spain[12] over seventeen weeks. Locations included Segovia, where Lester had made A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Lester says the producers assembled twenty minutes of footage and sold the film to 20th Century Fox.[13]

Lester says Michel Legrand "had about a week and a half" to write the music.[14]

Reception[]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 83% based on reviews from 12 critics.[15]

Variety gave the film a positive review, and wrote: "The Three Musketeers take very well to Richard Lester’s provocative version that does not send it up but does add comedy to this adventure tale". They praised the various performances, but noted that although Dunaway is underused she gets to make up for it in the sequel.[16] Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote: "Mr. Lester seems almost exclusively concerned with action, preferably comic, and one gets the impression after a while that he and his fencing masters labored too long in choreographing the elaborate duels. They're interesting to watch, though they are without a great deal of spontaneity."[17]

Awards and nominations[]

Raquel Welch won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy for her performance. The film was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.

George MacDonald Fraser won the Writers' Guild of Great Britain Award for Best British Comedy Screenplay.

Salkind Clause[]

The film was originally intended to be an epic which ran for three hours including an intermission, but during production, it was determined the film could not make its announced release date in that form, so a decision was made to split the longer film into two shorter features, the second part becoming 1974's The Four Musketeers.

Though some actors knew of this decision earlier than others, by the time of the Paris premiere of M3 all had been informed. Screenwriter George MacDonald Fraser records the evening, "That not all the actors knew about this I didn't discover until the Paris premiere, which began with a dinner for the company at Fouquet's and concluded in the small hours with a deafening concert in what appeared to be the cellar of some ancient Parisian structure (the Hotel de Ville, I think). Charlton Heston knew, for when we discussed it before dinner he shrugged philosophically and remarked: 'Two for the price of one.'"[18] This incensed the actors and crew, since they were being paid for one film, and their original contracts made no mention of a second feature, resulting in lawsuits being filed to receive compensation for salaries associated with the sequel.

This led to the Screen Actors Guild requiring all future actors' contracts to include what has become known as the "Salkind clause" (named after producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind), which stipulates that single productions cannot be split into film instalments without prior contractual agreement.[19][20]

Sequels[]

The Four Musketeers was released the following year, with footage originally intended to combine with this film's to be part of a much longer film.

In 1989, much of the cast and crew of the original returned to film The Return of the Musketeers, loosely based on Dumas' 1845 novel Twenty Years After.

References[]

- ^ Shivas, Mark (5 August 1973). "Lester's Back and the 'Musketeers' Have Got Him". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Sloman, Tony (25 March 1997). "Obituary: Alexander Salkind". Independent. London. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Lester's Back and the 'Musketeers' Have Got Him By MARK SHIVAS. New York Times 5 Aug 1973: 105

- ^ Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1. p232.

- ^ Jump up to: a b George MacDonald Fraser, The Light's On at Signpost, HarperCollins 2002 p1-16

- ^ Soderbergh p109

- ^ Jump up to: a b Soderbergh p 109

- ^ Jump up to: a b At the Movies: Costs of making 'Superman' go up, up and away. Buckley, Tom. New York Times 26 May 1978: C6.

- ^ Soderberg p 110

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Bart Signs Paramout Pact Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times 8 Aug 1973: d13.

- ^ Soderbergh p110

- ^ "Filming Locations for The Three Musketeers (1973), in Spain". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations.

- ^ Sodeberg p 110

- ^ Soderbergh p 113

- ^ "The Three Musketeers (1973)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "The Three Musketeers - The Queen's Diamonds". Variety. 31 December 1972. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (4 April 1974). "Spirites 'Three Musketeers' (No. 6)". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Fraser, George MacDonald (2002). The Light's on at Signpost (First ed.). London: HarperCollins. p. 8. ISBN 0007136463.

- ^ Russo, Tom (9 April 2004). "Franchise This". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Salmans, Sandra (17 July 1983). "FILM VIEW; THE SALKIND HEROES WEAR RED AND FLY HIGH". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

Bibliography[]

- Soderbergh, Steven; Lester, Richard (1999). Getting away with it : or, The further adventures of the luckiest bastard you ever saw. Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571190256.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Three Musketeers (1973 film) |

- 1973 films

- English-language films

- 1970s historical adventure films

- British films

- British historical adventure films

- American historical adventure films

- American films

- Films scored by Michel Legrand

- Films based on The Three Musketeers

- Films directed by Richard Lester

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actress Golden Globe winning performance

- Films shot in Madrid

- American swashbuckler films

- British swashbuckler films

- Films set in France

- Films set in Paris

- Films with screenplays by George MacDonald Fraser

- Cultural depictions of Cardinal Richelieu

- Cultural depictions of Louis XIII

- Films shot in Segovia