How to Make a Monster (1958 film)

| How to Make a Monster | |

|---|---|

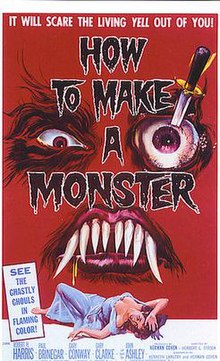

Theatrical release poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | Herbert L. Strock |

| Written by | Herman Cohen Aben Kandel |

| Produced by | Herman Cohen James H. Nicholson |

| Starring | Robert H. Harris Gary Conway Gary Clarke Morris Ankrum |

| Cinematography | Maury Gertsman |

| Music by | Paul Dunlap |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 73 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $100,000 (est.)[1] |

How to Make a Monster is a 1958 American horror film drama, produced and written by Herman Cohen, directed by Herbert L. Strock, and starring Gary Conway, Robert H. Harris, Paul Brinegar, Morris Ankrum, Robert Shayne, and John Ashley. The film was released by American International Pictures as a double feature with Teenage Caveman.

The film is a follow-up to both I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. Like Teenage Frankenstein, a black-and-white film that switches to color in its final moments, How to Make a Monster was filmed in black-and-white and only the last reel is in full color.

Plot[]

Pete Dumond, chief make-up artist for 25 years at American International Studios, is fired after the studio is purchased by NBN Associates. The new management from the East, Jeffrey Clayton and John Nixon, plan to make musicals and comedies instead of the horror pictures for which Pete has created his remarkable monster make-ups and made the studio famous. In retaliation, Pete vows to use the very monsters these men have rejected to destroy them. By mixing a numbing ingredient into his foundation cream and persuading the young actors that their careers are through unless they place themselves in his power, he hypnotizes both Larry Drake and Tony Mantell (who are playing the characters the Teenage Werewolf and the Teenage Frankenstein, respectively, in the picture Werewolf Meets Frankenstein, currently shooting on the lot).

Through hypnosis, Pete urges Larry, in Teenage werewolf make-up, to kill Nixon in the studio projection room. Later, he wills the unknowing Tony, in Teenage Frankenstein make-up, to wait for Clayton in his garage at night and brutally choke him to death. Studio guard Monahan, a self-styled detective, stops in at the make-up room on his rounds one evening. He shows Pete and Rivero, Pete's reluctant assistant and accomplice, his little black book in which he has jotted down many facts, such as the late time Pete and Rivero checked out the night of the first murder. By this show of initiative, he plans to get a promotion. Apprehensive, Pete—made up as a terrifying Prehistoric Man, one of his own creations—kills Monahan in the studio commissary while on his beat.

Richards, the older guard, sees and hears nothing until he uncovers Monahan's body. Police investigators uncover two clues: a maid, Millie, describes Frankenstein's monster (Tony, in make-up), who struck her down as he fled from Clayton's murder and the police laboratory technician discovers a peculiar ingredient in the make-up left on Clayton's fingers from his death struggle with Tony. The formula matches bits found in Pete's old make-up room. The police head for Pete's house. Pete has taken Rivero, Larry and Tony for a grim farewell party to his home, which is a museum of all the monsters that he has created in his 25 years at the studio. Pete has stabbed Rivero to death secretly in the kitchen and hidden his body. Finding Larry and Tony trying to escape the locked living room, he attacks them with a knife. Larry inadvertently knocks over a candelabra, setting the living room on fire, and Pete is burned to death, trying in vain to save the lifelike heads of his monster "children" mounted on the wall. The police break through the door before the flames reach the boys and save them.

Cast[]

- Robert H. Harris as Pete Dumond

- Gary Conway as Tony Mantell / the Teenage Frankenstein

- Gary Clarke as Larry Drake / the Teenage Werewolf

- Paul Brinegar as Rivero

- Malcolm Atterbury as Security Guard Richards

- Dennis Cross as Security Guard Monahan

- Morris Ankrum as Police Capt. Hancock

- Walter Reed as Detective Thompson

- Paul Maxwell as Jeffrey Clayton

- Eddie Marr as John Nixon

- Heather Ames as Arlene Dow

- Robert Shayne as Gary Droz

- John Phillips as Detective Jones

- Paulene Myers as Millie

- John Ashley as himself

Production[]

Many of Pete Dumond's "children" destroyed in the fire were props originally created by Paul Blaisdell for earlier AIP films. They include The She-Creature (1956), It Conquered the World (1956), Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957) and Attack of the Puppet People (1958).[2]

Herman Cohen says he cast John Ashley as a singer at the request of James H. Nicholson, who had put Ashley under long-term contract with the studio. Ashley was having some minor success as a recording artist at the time.[3][4]

AIP did not have a studio, so the film was shot at Ziv Studios. During production there, a sign was put up that called the complex "American International Studios".[5]

Ed Wood's widow Kathy claimed in a 1992 interview that her husband always felt that the idea for How To Make a Monster was stolen from him by AIP producer Sam Arkoff. She said "Eddie condemned Arkoff, he really hated him. Eddie gave them a script for approval, and they changed the characters a little bit around. Eddie had written it for Lugosi. It was about this old horror actor who couldn't get work any more, so he took his vengeance out on the studio. (They changed it to) a make-up man who takes revenge on a studio". Arkoff denied Wood's claim was true, stating Herman Cohen originated the entire project.[6]

Legacy[]

In recent years, the title has been used several times: for a song on Rob Zombie's 1998 debut solo album, Hellbilly Deluxe; for a TV movie in 2001; for the name of the 2004 album by The Cramps; for a documentary on special make-up effects applications in 2005; and for an 8-minute short film in 2011.

Scream Factory's 2020 Blu-ray release features an audio commentary by Tom Weaver.

Svengoolie featured the film on June 12, 2021 and again on December 11, 2021.

References[]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

- ^ Lamont, John (1990). "The John Ashley Filmography". Trash Compactor. Vol. 2 no. 5. p. 26.

- ^ Mark McGee, Faster and Furiouser: The Revised and Fattened Fable of American International Pictures, McFarland 1996, p. 94

- ^ Tom Weaver, "Interview with Herman Cohen" Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 17 December 2012

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (December 2019). "A Hell of a Life: The Nine Lives of John Ashley". Diabolique Magazine.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gary A. Smith, American International Pictures: The Golden Years, Bear Manor Media 2013, p. 89

- ^ Rudolph Grey, Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood, Jr. (1992). pg. 62. ISBN 978-0-922915-24-8.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: How to Make a Monster (1958 film) |

- 1958 films

- English-language films

- 1958 horror films

- 1950s teen films

- American films

- American International Pictures films

- Films about actors

- Films directed by Herbert L. Strock

- American werewolf films

- Films scored by Paul Dunlap

- American black-and-white films

- Films partially in color

- Mad scientist films