Horror film

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

|

| Speculative fiction |

|---|

|

|

A horror film is one that seeks to elicit fear or disgust in its audience for entertainment purposes.[1] Horror films additionally aim to evoke viewers' nightmares, revulsions and terror of the unknown or the macabre. Initially inspired by literature from authors such as Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, and Mary Shelley, horror has existed as a film genre for more than a century. Horror may also overlap with the fantasy, supernatural fiction, and thriller genres.

Plots within the horror genre often involve the intrusion of an evil force, event, or personage into the everyday world. Prevalent elements include ghosts, vampires, werewolves, evil witches, cults, black magic, demons and demonic possession, Satanism and the Devil, monsters, mummies, extraterrestrials, zombies, dystopian or apocalyptic worlds, disturbed children, gore and torture, cannibalism, natural forces, evil clowns, psychopaths and serial killers.

An example of sub-genre is psychological horror.[2]

1890s–1910s

The first depictions of the supernatural on screen appeared in several of the short silent films created by the French pioneer filmmaker Georges Méliès in the late 1890s. The best known of these early supernatural-based works is the 2 and a half-minute short film Le Manoir du Diable (1896), known in English as both The Haunted Castle or The House of the Devil. The film is sometimes credited as being the first ever horror film.[3] In The Haunted Castle, a mischievous devil appears inside a medieval castle where he harasses the visitors. Méliès' other popular horror film is La Caverne maudite (1898), which translates literally as "the accursed cave". The film, also known by its English title The Cave of the Demons, tells the story of a man stumbling over a cave that is populated by the spirits and skeletons of people who died there.[3] Méliès would also make other short films that historians consider now as horror-comedies. Une nuit terrible (1896), which translates to A Terrible Night, tells a story of a man who tries to get a good night's sleep but ends up wrestling a giant spider. His other film, L'auberge ensorcelée (1897), or The Bewitched Inn, features a story of a hotel guest being pranked and tormented by an unseen presence.[4]

In 1897, the American photographer-turned director George Albert Smith created The X-Ray Fiend (1897), a horror-comedy trick film that came out a mere two years after x-rays were invented. The film shows a couple of skeletons courting each other. An audience full of people unaccustomed to seeing moving skeletons on screen would have found it frightening and otherworldly.[5] The next year, Smith created the short film Photographing a Ghost (1898), considered a precursor to the paranormal investigation subgenre. The film portrays three men attempting to photograph a ghost, only to fail time and again as the ghost eludes the men and throws chairs at them.

Japan also made early forays into the horror genre. In 1898, a Japanese film company called Konishi Honten released two horror films both written by Ejiro Hatta. These were (Resurrection of a Corpse), and (Jizo the Spook)[6] The film Shinin No Sosei told the story of a dead man who comes back to life after having fallen from a coffin that two men were carrying. The writer Hatta played the dead man role, while the coffin-bearers were played by Konishi Honten employees. Though there are no records of the cast, crew, or plot of Bake Jizo, it was likely based on the Japanese legend of Jizo statues, believed to provide safety and protection to children. In Japan, Jizō is a deity who is seen as the guardian of children, particularly children who have died before their parents. Jizō has been worshiped as the guardian of the souls of mizuko, namely stillborn, miscarried, or aborted fetuses.

Spanish filmmaker Segundo de Chomón is also one of the most significant silent film directors in early filmmaking.[7] He was popular for his frequent camera tricks and optical illusions, an innovation that contributed heavily to the popularity of trick films in the period. His famous works include Satán se divierte (1907), which translates to Satan Having Fun, or Satan at Play; La casa hechizada (1908), or The House of Ghosts, considered to be one of the earliest cinematic depictions of a haunted house premise; and (1907) or The Red Spectre, a collaboration film with French director Ferdinand Zecca about a demonic magician who attempts to perform his act in a mysterious grotto.

The Selig Polyscope Company in the United States produced one of the first film adaptations of a horror-based novel. In 1908, the company produced the film Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, directed by Otis Turner and starring Hobart Bosworth in the lead role. The film is, however, now considered a lost film. The story was based on Robert Louis Stevenson's classic gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, published 15 years prior, about a man who transforms his personality between two contrasting personas. (The book tells the classic story of a man with an unpredictably dual nature: usually very good, but sometimes shockingly evil as well.)

Georges Méliès also liked adapting the Faust legend into his films. In fact, the French filmmaker produced at least six variations of the German legend of the man who made a pact with the devil. Among his notable Faust films include Faust aux enfers (1903), known primarily for its English title The Damnation of Faust, or Faust in Hell. It is the filmmaker's third film adaptation of the Faust legend. In it, Méliès took inspiration from Hector Berlioz's Faust opera, but it pays less attention to the story and more to the special effects that represent a tour of hell. The film takes advantage of stage machinery techniques and features special effects such as pyrotechnics, substitution splices, superimpositions on black backgrounds, and dissolves.[8] Méliès then made a sequel to that film called Damnation du docteur Faust (1904), released in the U.S. as Faust and Marguerite. This time, the film was based on the opera by Charles Gounod. Méliès' other devil-inspired films in this period include Les quat'cents farces du diable (1906), known in English as The Merry Frolics of Satan or The 400 Tricks of the Devil, a tale about an engineer who barters with the Devil for superhuman powers and is forced to face the consequences. Méliès would also make other horror-based short films that aren't inspired by Faust, most notably the fantastical and unsettling Le papillon fantastique (1909), where a magician turns a butterfly woman into a spider beast.

In 1910, Edison Studios in the United States produced the first filmed version of Mary Shelley's 1818 classic Gothic novel Frankenstein, the popular story of a scientist creating a hideous, sapient creature through a scientific experiment. Adapted to the screen for the first time by director J. Searle Dawley, his movie Frankenstein (1910) was deliberately designed to de-emphasize the horrific aspects of the story and focus on the story's mystical and psychological elements.[9] Yet, the macabre nature of its source material made the film synonymous with the horror film genre.[10]

The United States continued producing films based on the 1886 Gothic novella the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, a classic tale about a doctor or scientist whose evil persona emerges after getting in contact with a magical formula. New York City's Thanhouser Film Corporation's one-reel Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1912) was directed by Lucius Henderson and stars future director James Cruze in the title role. A year later, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1913) came out. This time it was independently produced by IMP (the future Universal Studios) and stars King Baggot as the doctor.[11]

In March 1911, the hour-long Italian silent film epic L'Inferno was screened in the Teatro Mercadante in Naples.[12] The film was adapted from the first part of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy and took visual inspiration from Gustave Doré's haunting illustrations. It is widely considered to be the best adaptation of The Inferno and is regarded by many scholars as the finest film adaptation of any of Dante's works to date. The film became an international success and is arguably the first true blockbuster in all of cinema. L'Inferno was directed by three artists; Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, and Giuseppe de Liguoro. Their film is well-remembered for its stunning visualization of the nine circles of Hell and special effects that convey haunting visuals. The film presents a massive Lucifer with wings that stretch out behind him in front of a black void. He is seen devouring the Roman figures Brutus and Cassius in a display of double exposure and scale manipulation. According to critics, L'Inferno is able to capture some of the manic, tortuous, and bizarre imagery and themes of Dante's complex masterwork.[13]

In the 1910s Georges Méliès would continue producing his Faustian films, the most significant of this period was 1912's Le Chevalier des Neiges (The Knight of the Snows). It was Méliès' last film with Faustian themes[14] and the last of many films in which the filmmaker appeared as the Devil.[15] The film tells a story of a princess kidnapped by Satan and thrown into a dungeon. Her lover, the brave Knight of the Snows, must then go on a journey to rescue her. Special effects in the film were created with stage machinery, pyrotechnics, substitution splices, superimpositions, and dissolves.[15] It is among a few of the best examples of trick films that Georges Méliès and Segundo de Chomón helped popularized.

In 1912, French director Abel Gance released his short film Le masque d'horreur (The Mask of Horror). The film tells a story of a mad sculptor who searches for the perfect realization of "the mask of horror". He places himself in front of a mirror after smearing blood over himself with the glass of an oil lamp. He then swallows a virulent poison to observe the effects of pain.[16]

In 1913, German directors Stellan Rye and Paul Wegener made the silent horror film Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague) loosely based on a short story by Edgar Allan Poe. The film tells a story of a student who inadvertently makes a Faustian bargain. In the film, a student asks a stranger to turn him into a rich man. The stranger visits the student later in his dorm room and conjures up pieces of gold and a contract for him to sign. In return, the stranger is granted to take anything he wants from the room. He chooses to take the student's mirror. Upon moving it from the wall, a doppelgänger steps out and causes trouble. (In Western culture, a doppelgänger is a supernatural or ghostly double or look-alike of a specific person. It is usually seen as a harbinger of bad luck.) Cinematographer Guido Seeber utilized groundbreaking camera tricks to create the effect of the doppelgänger by using a mirror double which produces a seamless double exposure. The film was written by Hanns Heinz Ewers, a noted writer of horror and fantasy stories. His involvement with the screenplay lent a much needed air of respectability to the fledgling art form of horror film and German Expressionism[17]

From November 1915 until June 1916, French writer/director Louis Feuillade released a weekly serial entitled Les Vampires where he exploited the power of horror imagery to great effect. Consisting of 10 parts or episodes and roughly 7 hours long if combined, Les Vampires is considered to be one of the longest films ever made. The series tells a story of a criminal gang called the Vampires, who play upon their supernatural name and style to instill fear in the public and the police who desperately want to put a stop to them.[18] Marked as Feuillade's legendary opus, Les Vampires is considered a precursor to movie thrillers. The series is also a close cousin to the surrealist movement.[19]

Paul Wegener followed up the success of The Student of Prague by adapting a story inspired by the ancient Jewish legend of the golem, an anthropomorphic being magically created entirely from clay or mud. Wegener teamed up with Henrik Galeen to create Der Golem (1915). The film, which is still partially lost, tells a story of an antiques dealer who finds a golem, a clay statue, brought to life centuries before. The dealer resurrects the golem as a servant, but the golem falls in love with the antiques dealer's wife. As she does not return his love, the golem commits a series of murders. Wegener made a sequel to the film two years later.This time he teamed up with co-director Rochus Gliese and made Der Golem und die Tänzerin (1917), or The Golem and the Dancing Girl as it is known in English. It is now considered a lost film. Wegener would make a third golem film another three years later to conclude his Der Golem trilogy.

In 1919, Austrian director Richard Oswald released a German silent anthology horror film called Unheimliche Geschichten, also known as Eerie Tales or Uncanny Tales. In the film, a bookshop closes and the portraits of the Strumpet, Death, and the Devil come to life and amuse themselves by reading stories—about themselves, of course, in various guises and eras. The film is split into five stories: The Apparition, The Hand, The Black Cat (based on the Edgar Allan Poe short story), The Suicide Club (based on the Robert Louis Stevenson short story collection) and Der Spuk (which translates to The Spectre in English). The film is described as the "critical link between the more conventional German mystery and detective films of the mid 1910s and the groundbreaking fantastic cinema of the early 1920s."[20]"

Trick films

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, artists and engineers were all pushing the boundaries of film. Artists like Méliès first achieved fame as a magician. During the time, stage magicians entertained large crowds with illusions and magic tricks, and decked out their sets with elaborate sets, costumes, and characters. While filmmakers like the Lumière brothers were tinkering with motion picture devices and shot documentary-like films, Méliès, and to an extent, Segundo de Chomón as well, were developing magic tricks on film. They created sophisticated sight gags and theatrical special effects to either entertain or scare the audience.[21]

In his autobiography, Méliès recalled a day when he was capturing footage on a Paris street when his camera jammed. Frustrated, he fiddled with the hand crank, fixed the problem, and started shooting again. When he developed the film later and played it back, he discovered a new trick. The shot started with people walking, children skipping, and a horse-drawn omnibus workers trundling up the street. Then, in the blink of an eye, everything changed. Men turned into women, children were replaced by horses, and – spookiest of all – the omnibus full of workers changed into a hearse. Because of this, Méliès had found a way to perform actual magic with editing, to fool an audience and pull off illusions he'd never been able to do on stage. This was the birth of trick films.[21]

Most of the early films in cinema history consist of continuous shots of short skits and/or scenes from everyday life [i.e., The Kiss (1898) or Train Pulling into a Station (1896)]. Filmmakers doing trick films attempted to do the impossible on screen; like levitating heads, making people disappear, or turning them into skeletons. Trick films were silent films designed to feature innovative special effects. This style of filmmaking was developed by innovators such as Georges Méliès and Segundo de Chomón in their first cinematic experiments. In the first years of film, especially between 1898 and 1908, the trick film was one of the world's most popular film genres. Techniques explored in these trick films included slow motion and fast motion created by varying the camera cranking speed; the editing device called the substitution splice; and various in-camera effects, such as .[22] Double exposures, especially, are achieved to show faded or ghostly images on the screen.

The spectacular nature of trick films lives on especially in horror films. Trick films convey energetic whimsy that makes impossible events seem to occur on screen. Trick films are in essence films in which artists use camera techniques to create magic tricks or special effects that feel otherworldly. Other examples of trick films include 1901's The Big Swallow in which a man tries to swallow the audience, and 1901's The Haunted Curiosity Shop in which apparitions appear inside an antique shop.[23]

1920s

German Expressionism

Robert Wiene's 1920 Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) became a worldwide success and had a lasting impact on the film world, particularly for horror. It was not so much the story but the style that made it distinguishable from other films, "Dr. Caligari's settings, some simply painted on canvas backdrops, are weirdly distorted, with caricatures of narrow streets, misshapen walls, odd rhomboid windows, and leaning doorframes. Effects of light and shadow were rendered by painting black lines and patterns directly on the floors and walls of sets."[24] Critic Roger Ebert called it arguably "the first true horror film", and film reviewer Danny Peary called it cinema's first cult film and a precursor to arthouse films. Considered a classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari helped draw worldwide attention to the artistic merit of German cinema and had a major influence on American films, particularly in the genres of horror and film noir, introducing techniques such as the twist ending and the unreliable narrator to the language of narrative film. Writing for the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, horror film critic Kim Newman called The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari "a major early entry in the horror genre, introducing images, themes, characters, and expressions that became fundamental to the likes of Tod Browning's Dracula and James Whales' Frankenstein, both from 1931".[25] The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is also a leading example of what a German Expressionist film looks like.

In October 1920, Paul Wegener teamed up with co-director Carl Boese to make the final Golem film entitled Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam, known in English as The Golem: How He Came into the World. The final film in the Der Golem trilogy is a prequel to Der Golem from 1915. In this film, Wegener stars as the golem who frightens a young lady with whom he is infatuated. The film is the best known of the series, as it is the only film that is completely preserved. It is also a leading example of early German Expressionism.

F. W. Murnau arguably made the first vampire-themed movie, Nosferatu (1922). It was an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's gothic horror novel Dracula. In Nosferatu, Murnau created some of cinema's most lasting and haunting imagery which famously involve shadows of the creeping Count Orlok. This helped popularized the expressionism style in filmmaking. Many expressionist works of this era emphasize a distorted reality, stimulating the human psyche and have influenced the horror film genre.

For most of the 1920s, German filmmakers like Wegener, Murnau, and Wiene would significantly influence later productions not only in horror films but in filmmaking in general. They would become the leading innovators of the German Expressionist movement. The plots and stories of the German Expressionist films often dealt with madness and insanity. Arthur Robison's film, Schatten – Eine nächtliche Halluzination (1923), literally Shadows – a Nocturnal Hallucination, also known as Warning Shadows in English, is also one of the leading German Expressionist films. It tells the story of house guests inside a manor given visions of what might happen if the manor's host, the count played by Fritz Kortner, stays jealous and the guests do not reduce their advances towards his beautiful wife. Kortner's bulging eyes and twisted features are facets of a classic Expressionist performance style, as his unnatural feelings contort his face and body into something that appears other than human.[26]

In 1924, German filmmaker Paul Leni made another representative German Expressionist film with Das Wachsfigurenkabinett, or Waxworks as it is commonly known. The horror film tells a story of a writer who accepts a job from a wax museum to write a series of stories on different controversial figures including Ivan the Terrible and Jack the Ripper in order to boost business. Although Waxworks is often credited as a horror film, it is an anthology film that goes through several genres including a fantasy adventure, historical film, and horror film through its various episodes. Waxworks contain many elements present in a German Expressionist movie. The film features deep shadows, moving shapes, and warped staircases. The director said of the film, "I have tried to create sets so stylized that they evidence no idea of reality." Waxworks was director Paul Leni's last film in Germany before heading to Hollywood to make some of the most important horror films of the late silent era.[citation needed]

Universal Classic Monsters (silent era)

Though the word horror to describe the film genre would not be used until the 1930s (when Universal Pictures began releasing their initial monster films), earlier American productions often relied on horror and gothic themes. Many of these early films were considered dark melodramas because of their stock characters and emotion-heavy plots that focused on romance, violence, suspense, and sentimentality.[27]

In 1923, Universal Pictures started producing movies based on Gothic Horror literature from authors like Victor Hugo and Edgar Allan Poe. This series of pictures from Universal Pictures have retroactively become the first phase of the studio's Universal Classic Monsters series that would continue for three more decades. Universal Pictures' classic monsters of the 1920s featured hideously deformed characters like Quasimodo, The Phantom, and Gwynplaine.

The first film of the series was The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) starring Lon Chaney as the hunchback Quasimodo. The film was adapted from the classic French gothic novel of the same name written by Victor Hugo in 1833, about a horribly deformed bell ringer in the cathedral of Notre-Dame. The film elevated Chaney, already a well-known character actor, to full star status in Hollywood, and also helped set a standard for many later horror films.

Two years later, Chaney stars as The Phantom who haunts the Paris Opera House in 1925's silent horror film, The Phantom of the Opera, based on the mystery novel by Gaston Leroux published 15 years earlier. Roger Ebert said the film "creates beneath the opera one of the most grotesque places in the cinema, and Chaney's performance transforms an absurd character into a haunting one."[28] Adrian Warren of PopMatters called the film "terrific: unsettling, beautifully shot and imbued with a dense and shadowy Gothic atmosphere".[29] Included in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, 1925's The Phantom of the Opera is lauded for Lon Chaney's masterful acting, Universal Pictures' incredible set design, and its many masterly moments including the unmasking of the tragic villain's disfigured skullface, so shocking that even the camera is terrified, going briefly out of focus.[30]

In 1927, German director Paul Leni directed his first of two films for Universal Pictures. His silent horror film The Cat and the Canary is the third film in the Universal Classic Monsters series and is considered "the cornerstone of Universal's school of horror."[31] The Cat and the Canary is adapted from John Willard's black comedy play of the same name. The plot revolves around the death of a man and the reading of his will 20 years later. His family inherits his fortunes, but when they spend the night in his haunted mansion they are stalked by a mysterious figure. Meanwhile, a lunatic known as "the Cat" escapes from an asylum and hides in the mansion. The film is part of a genre of comedy horror films inspired by 1920s Broadway stage plays. Paul Leni's adaptation of Willard's play blended expressionism with humor, a style Leni was notable for and critics recognized as unique. Alfred Hitchcock cited this film as one of his influences[32] and Tony Rayns called it the "definitive haunted house movie."[33]

Paul Leni's second film for Universal Pictures was The Man Who Laughs (1928), an adaptation of another Victor Hugo novel. The film, starring Conrad Veidt is known for the bleak carnival freak-like grin on the character Gwynplaine's face. His exaggerated smile was the inspiration for DC Comics' The Joker. (A graphic novel in 2005 exploring the origins of the Joker was also titled Batman: The Man Who Laughs in homage to this film).[34] Film critic Roger Ebert stated, "The Man Who Laughs is a melodrama, at times even a swashbuckler, but so steeped in Expressionist gloom that it plays like a horror film".[35]

The fifth and last film of the Universal Classic Monsters series in the 1920s is The Last Performance (1929). It was directed by Paul Fejos and stars Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin. Veidt plays a middle-aged magician who is in love with his beautiful young assistant. She, on the other hand, is in love with the magician's young protege, who turns out to be a bum and a thief. The film received mixed reviews and a 1929 New York Times article even said that "Dr. Fejos has handled his scenes with no small degree of imagination."[36]

Other productions in the 1920s

The trend of inserting an element of macabre into American pre-horror melodramas was popular in the 1920s. Directors known for relying on macabre in their films during the decade were Maurice Tourneur, Rex Ingram, and Tod Browning. Ingram's The Magician (1926) contains one of the first examples of a "mad doctor" and is said to have had a large influence on James Whale's version of Frankenstein.[37] The Unholy Three (1925) is an example of Tod Browning's use of macabre and unique style of morbidity; he remade the film in 1930 as a talkie. In 1927, Tod Browning cast Lon Chaney in his horror film The Unknown. Chaney played a carnival knife thrower called Alonzo the Armless and Joan Crawford as the scantily clad carnival girl he hopes to marry. Chaney did collaborative scenes with a real-life armless double whose legs and feet were used to manipulate objects such as knives and cigarettes in frame with Chaney's upper body and face.[38]

1928's The Terror by Warner Bros. Pictures was the first all-talking horror film, made using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system.[39] The film tells a simple story of guests at an old English manor being stalked by a mysterious killer known only as "The Terror". The plot centered on sound, with much of the ghost's haunting taking place in vis-a-vis creepy organ music, creaky doors and howling winds. The film was poorly received by audiences and critics. John MacCormac, reporting from London for The New York Times upon the film's UK premiere, wrote; "The universal opinion of London critics is that The Terror is so bad that it is almost suicidal. They claim that it is monotonous, slow, dragging, fatiguing and boring."[40]

Other European countries also, contributed to the genre during this period. In Sweden, Victor Sjöström created Körkarlen (The Phantom Carriage) in 1921. This is what the Criterion have to say about the film; "The last person to die on New Year's Eve before the clock strikes twelve is doomed to take the reins of Death's chariot and work tirelessly collecting fresh souls for the next year. So says the legend that drives The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen), directed by the father of Swedish cinema, Victor Sjöström. The story, based on a novel by Nobel Prize winner Selma Lagerlöf, concerns an alcoholic, abusive ne’er-do-well (Sjöström himself) who is shown the error of his ways, and the pure-of-heart Salvation Army sister who believes in his redemption. This extraordinarily rich and innovative silent classic (which inspired Ingmar Bergman to make movies) is a Dickensian ghost story and a deeply moving morality tale, as well as a showcase for groundbreaking special effects."[41]

In 1922, Danish filmmaker Benjamin Christensen created the Swedish-Danish production Häxan (also known as The Witches or Witchcraft Through the Ages), a documentary-style silent horror film based partly on Christensen's study of the Malleus Maleficarum, a 15th-century German guide for inquisitors. Häxan is a study of how superstition and the misunderstanding of diseases and mental illness could lead to the hysteria of the witch-hunts.[2] The film was made as a documentary but contains dramatized sequences that are comparable to horror films.[42] To visualize his subject matter, Christensen fills the frame with every frightening image he can conjure out of the historical records, often freely blending fact and fantasy. There are shocking moments in which we witness a woman giving birth to two enormous demons, see a witches' sabbath, and endure tortures by inquisition judges. The film also features an endless parade of demons of all shapes and sizes, some of whom look more or less human, whereas others, are almost fully animal—pigs, twisted birds, cats, and the like.[43]

French filmmaker Jean Epstein produced an influential film, La Chute de la maison Usher (The Fall of the House of Usher) in 1928. It is one of multiple films based on the Edgar Allan Poe Gothic short story of the same name. Future director Luis Buñuel co-wrote the screenplay with Epstein, his second film credit, having previously worked as assistant director on Epstein's film Mauprat from 1926. Roger Ebert included the film on his list of "Great Movies" in 2002, calling the great hall of the film as "one of the most haunting spaces in the movies".[44]

Il mostro di Frankenstein (1921), one of only a few Italian horror films before the late 1950s, is now considered lost.[45]

1930s

Universal Classic Monsters (early sound era)

In the 1930s Universal Pictures continued producing films based on Gothic horror. The studio entered a Golden Age of monster movies in the '30s, releasing a string of hit horror movies. In this decade, the studio assembled several iconic monsters in motion picture history including Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, and The Invisible Man.[46] Each movie starring these monsters would go on to make sequels and each of the characters would go on to cross-over with one another in a cinematic shared universe. The films would retroactively be classified together as part of the Universal Classic Monsters series.[47]

Universal Pictures created a monopoly on the mainstream horror film, producing stars such as Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, and grossing large sums of money at the box office in the process. Not only did Universal bring the subgenre of "creature features" into the limelight, they also gave them their golden years, now reflected back on as "The Monsters Golden Era."[48] In the 1920s, the studio only put out five features, in the 1930s however, they produced about 21.

In the year 1930, Universal Pictures released the mystery film The Cat Creeps. It was a sound remake of the studio's earlier film, The Cat and the Canary from three years ago. Simultaneously, Universal also released a Spanish-speaking version of the film called La Voluntad del Muerto (The Will of the Dead Man). The film was directed by George Melford who would later direct the Spanish version of Dracula. Both The Cat Creeps and La Voluntad del Muerto are considered lost films.

1931: Dracula and Frankenstein

On 14 February 1931, Universal Pictures premiered their first film adaptation of Dracula, the popular story of an ancient vampire who arrives in England where he preys upon a virtuous young girl. The film was based on the 1924 stage play by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston, which in turn was loosely based on the classic 1897 novel by Bram Stoker. February 1931's Dracula was an English-language vampire-horror film directed by Tod Browning and stars Bela Lugosi as the Count Dracula, the actor's most iconic role. The film was generally well received by critics. Variety praised the film for its "remarkably effective background of creepy atmosphere."[49] Film Daily declared it "a fine melodrama" and also lauded Lugosi's performance, calling it "splendid" and remarking that he had created "one of the most unique and powerful roles of the screen".[50] Kim Newman, writing for the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, said that Dracula signaled the "true beginning of the horror film as a distinct genre and the vampire movie as its most popular subgenre."[51]

Two months later on 24 April 1931, Universal Pictures premiered the Spanish-language version of Dracula directed by George Melford. April 1931's Drácula was filmed at night on the same sets that were being used during the day for the English-language version. Of the cast, only Carlos Villarías (playing Count Dracula) was permitted to see rushes of the English-language film, and he was encouraged to imitate Bela Lugosi's performance. Some long shots of Lugosi as the Count and some alternative takes from the English version were used in this production.[52] In recent years, this version has become more highly praised than Tod Browning's English-language version.[53] The Spanish crew had the advantage of watching the English dailies when they came in for the evening, and they would devise better camera angles and more effective use of lighting in an attempt to improve upon it.[54] In 2015, the Library of Congress selected the film for preservation in the National Film Registry, finding it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[55]

in the 1935 Bride of Frankenstein.

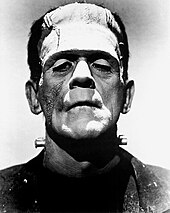

On 21 November 1931, Universal Pictures released another hit film with Frankenstein. The story is about a scientist and his assistant who dig up corpses in the hope of reanimating them with electricity. The experiment goes awry when Dr. Frankenstein's assistant accidentally gives the creature a murderer's abnormal brain. 1931's Frankenstein was based on a 1927 play by Peggy Webling which in turn was based on Mary Shelley's classic 1818 Gothic novel. The film was directed by James Whale and stars Boris Karloff as Frankenstein's monster in one of his most iconic roles. A hit with both audiences and critics, the film was followed by multiple sequels and along with the same year's Dracula, has become one of the most famous horror films in history. "Universal’s makeup artist Jack Pierce created the main look of the monster, devising the flattop, the neck terminals, the heavy eyelids, and the elongated scarred hands, while director James Whale outfitted the creature with a shabby suit."[56]

At the end of 1931, Paramount came out with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, starring Fredric March, who shared the Best Actor Oscar with Wallace Beery for The Champ. March is the first actor to win the Best Actor Oscar for a portrayal in a horror role.[57]

1932: Edgar Allan Poe double-feature and The Mummy

On 21 February 1932, Universal Pictures released a double-feature. The first one is Murders in the Rue Morgue. It stars Bela Lugosi as a lunatic scientist who abducts women and injects them with blood from his ill-tempered caged ape. The film was loosely based on an 1841 short story by Edgar Allan Poe. Universal Pictures would release two more Poe adaptations later in the decade. The second film in the double-feature is the James Whale-directed The Old Dark House. It's a mystery horror story starring Boris Karloff. Five travelers are admitted to a large foreboding old house that belongs to an extremely strange family. The story was based on a 1927 novel by J.B. Priestly.

In December 1932, the studio released The Mummy starring Boris Karloff as the Egyptian monster. The film, based on an original screenplay, is about an ancient Egyptian mummy named Imhotep who is discovered by a team of archaeologists and inadvertently brought back to life through a magic scroll. Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports a 93% score, based on 27 reviews, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The site's consensus states: "Relying more on mood and atmosphere than the thrills typical of modern horror fare, Universal's The Mummy sets a masterful template for mummy-themed films to follow."[58] The Mummy character was so popular that it spawned sequels and remakes over the next decades.

Make-up artist Jack Pierce was responsible for the look of the Mummy. After studying photos of ancient mummies, Pierce came up with the look bearing a resemblance to the mummy of Ramesses III. Pierce began transforming Karloff at 11 a.m., applying cotton, collodion and spirit gum to his face; clay to his hair; and wrapping him in linen bandages treated with acid and burnt in an oven, finishing the job at 7 p.m. Karloff finished his scenes by 2 a.m., and another two hours were spent removing the make-up. Boris Karloff found the removal of gum from his face painful, and overall found the day "the most trying ordeal I [had] ever endured".[59] The image of Karloff wrapped in bandages has become one of the most iconic images in the series. Jack Pierce would also come to design the Satanic make-up for Lugosi in the independently produced White Zombie (1932).

1933: The Invisible Man

In 1933, after the release of The Mummy, Universal Pictures released two pictures. The first one was in July. It was a murder-mystery film called The Secret of the Blue Room. The plot of the film is that, according to legend, the "blue room" inside a mansion is cursed. Everyone who has ever spent the night there has met with an untimely end. Three men wager that each can survive a night in the forbidding room. In November, the studio premiered another iconic character with Dr. Jack Griffin, aka the Invisible Man in the classic science fiction-horror film The Invisible Man. The film was directed by James Whale and stars Claude Rains as the titular character. The movie was based on a science fiction novel of the same name by H. G. Wells published in 1897. The film has been described as a "nearly perfect translation of the spirit of the book".[60] It spawned a number of sequels, plus many spinoffs using the idea of an "invisible man" that were largely unrelated to Wells' original story.

The Invisible Man is known for its clever and groundbreaking visual effects by John P. Fulton, John J. Mescall and Frank D. Williams, whose work is often credited for the success of the film.[61] When the Invisible Man had no clothes on, the effect was achieved through the use of wires, but when he had some of his clothes on or was taking his clothes off, the effect was achieved by shooting Claude Rains in a completely black velvet suit against a black velvet background and then combining this shot with another shot of the location the scene took place in using a matte process. Claude Rains was claustrophobic and it was hard to breathe through the suit. Consequently, the work was especially difficult for him, and a double, who was somewhat shorter than Rains, was sometimes used.

1934: The Black Cat

In 1934, Universal Pictures released the successful psychological horror film The Black Cat. It stars both Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. It was the first of six movies where Universal Pictures paired the two iconic actors together. The Black Cat became Universal Pictures' biggest box office hit of the year and is considered by many to be the one that created and popularized the psychological horror subgenre, emphasizing on atmosphere, eerie sounds, the darker side of the human psyche, and emotions like fear and guilt to deliver its scares, something that was not used in the horror genre before. Although it was credited the film was based on Edgar Allan Poe's classic 1841 short story, the film actually has little to do with Poe's story. In the film, American honeymooners in Hungary become trapped in the home of a Satan-worshiping priest when the bride is taken there for medical help following a road accident. The film exploited a sudden public interest in psychiatry.[62] Peter Ruric (better known as pulp writer Paul Cain) wrote the screenplay.[63]

1935: Bride of Frankenstein

In 1935, Universal Pictures released four pictures from February to July. The first picture they released in 1935 was The Mystery of Edwin Drood, a mystery drama film starring Claude Rains. The story revolves around an opium-addicted choirmaster who develops an obsession for a beautiful young girl and will not stop short of murder in order to have her. The film was based on the final novel by Charles Dickens in 1870.

In April 1935, Bride of Frankenstein premiered. The science-fiction/horror film was the first sequel to the 1931 hit Frankenstein. It is widely regarded as one of the greatest sequels in cinematic history, with many fans and critics considering it to be an improvement on the original film. As with the original, Bride of Frankenstein was directed by James Whale and stars Boris Karloff as the Monster. In the film, Dr. Frankenstein, goaded by an even madder scientist, builds his monster a mate, often referred to as the Monster's Bride. Makeup artist Jack Pierce returned to create the makeup for the Monster and his Bride. Over the course of filming, Pierce modified the Monster's makeup to indicate that the Monster's injuries were healing as the film progressed.[64] Pierce co-created the Bride's makeup with strong input from Whale, especially regarding the Bride's iconic hair style, which was based on the Egyptian queen Nefertiti. Actress Elsa Lanchester portrayed the Monster's Bride. The bride's conical hairdo, with its white lightning-trace streaks on each side, has become an iconic symbol of both the character and the film.

A month after the release of Bride of Frankenstein, Universal Pictures premiered the influential werewolf movie Werewolf of London, the first Hollywood mainstream movie to feature a werewolf, a creature of folklore who shape-shifts from a human into a wolf. The film stars Henry Hull as the titular character. In the movie, he is a botanist who gets attacked by a strange animal. The bite causes him to turn into a bloodthirsty monster. Jack Pierce created the make-up for the creature. Screenwriter and journalist Frank Nugent, writing for The New York Times, thought the film was "designed solely to amaze and horrify." He continued by writing, "Werewolf of London goes about its task with commendable thoroughness, sparing no grisly detail and springing from scene to scene with even greater ease than that oft attributed to a daring young aerialist. Granting that the central idea has been used before, the picture still rates the attention of action-and-horror enthusiasts."[65] Six years later, Universal Pictures would release the second werewolf picture, The Wolf Man, which would garner greater deal of influence on Hollywood's depiction of the legend of the werewolf.[66]

In July 1935, Universal Pictures paired Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff together for a second time in the studio's third Edgar Allan Poe picture. The film was The Raven. The film was not actually a direct adaptation of the classic 1845 poem, but rather inspired from it. In the film, a brilliant surgeon, played by Bela Lugosi, is obsessed with the writer Edgar Allan Poe. He saves the life of a beautiful dancer but goes mad when he can't have her. Meanwhile, Boris Karloff plays a fugitive murderer on the run from the police. 1935's The Raven contains themes of torture, disfigurement, and grisly revenge. The film did not do particularly well at the box office during its initial release, and indirectly led to a temporary ban on horror films in England. At the time, it was beginning to look like the horror genre was no longer economically viable, and paired with the strict production code of the era, American filmmakers struggled to make creative works on screen, and horror eventually went out of vogue. This proved a devastating development at the time for Lugosi, who found himself losing work and struggling to support his family. Universal Pictures changed ownership in 1936, and the new management was less interested in the macabre.

1936: Dracula's Daughter

In 1936, Universal Pictures continued to make films for the series. In January, the studio premiered the science fiction melodrama The Invisible Ray. The film pairs Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff a third time. In the film, a scientist creates a telescope-like device that captures light waves from the Andromeda Galaxy, giving him a way to view the distant past. He and several colleagues go to Africa to locate a large, unusual meteorite that the light-waves showed fell there a billion years earlier. After discovering that the meteorite is composed of a poisonous unknown element, "Radium X", he begins to glow in the dark, and his touch becomes deadly. These radiation effects also begin to slowly drive him mad. Critics noted the tone of the film to be somber, dignified, and tragic. The Invisible Ray is a morality play, particularly given the film's final lines of dialog, uttered nine years before the events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, by Madame Rukh: "My son, you have broken the first law of science...Janos Rukh is dead, but part of him will go on to eternity, working for humanity".

In May 1936, Universal Pictures released a sequel to 1931's Dracula. The film was called Dracula's Daughter and stars Gloria Holden in the title role. Dracula's Daughter doesn't feature Bela Lugosi or his character, but instead tells the story of Countess Marya Zaleska, the daughter of Count Dracula and herself a vampire. Following Dracula's death, she believes that by destroying his body she will be free of his influence and live normally. When this fails, she turns to a psychiatrist, played by Otto Kruger. He, in turn, has a fiancé, Janet. The Countess kidnaps Janet and takes her to Transylvania, leading to a battle between Dr. Garth and the Countess. While not as successful as the original upon its release, the film was generally well-reviewed. In the intervening decades, criticism has been deeply divided. Contemporary critics and scholars have noted the film's strong lesbian overtones, which Universal acknowledged from the start of production and exploited in some early advertising. Universal would complete their initial Dracula trilogy seven years later with Son of Dracula.

1937–1939: The decline of the studio's Golden Age

In 1937, Universal Pictures released Night Key, a science fiction crime thriller starring Boris Karloff. In Night Key, Karloff plays an elderly inventor of a burglar alarm who attempts to get back at the man who stole the profits to his invention. Later, his device is subverted by gangsters who threaten him and use his own device to facilitate burglaries.

In 1938, Universal Pictures did not release any film related to horror, thriller, or science fiction. Instead, they made re-releases of their previous Dracula and Frankenstein films. It was only in January 1939, a full year and a half after the release of Night Key that the studio continued putting out original horror movies. On 7 January 1939, Universal Pictures premiered their 12-part serial The Phantom Creeps. It stars Bela Lugosi as a mad scientist who attempts to rule the world by creating various elaborate inventions. In a dramatic fashion, foreign agents and G-Men (government men) try to seize the inventions for themselves. A 78-minute version of the film, cut down from the serial's original 265 minutes, was released for television ten years later. The Phantom Creeps was Universal Pictures' 112th serial and 44th to have sound. The innovation of the scrolling text version of the synopsis at the beginning of each chapter was used for the Star Wars films as the "Star Wars opening crawl".

On 13 January 1939, Universal Pictures released Son of Frankenstein, the third entry in the studio's Frankenstein series and the last to feature Boris Karloff as the Monster. It is also the first to feature Bela Lugosi as Ygor. The film is the sequel to James Whale's Bride of Frankenstein, and stars top-billed Basil Rathbone, Karloff, Lugosi and Lionel Atwill. Son of Frankenstein was a reaction to the popular re-releases of Dracula and Frankenstein as double-features in 1938. In the film, one of the sons of Frankenstein finds his father's monster in a coma and revives him, only to find out he is controlled by Ygor who is bent on revenge. Universal's declining horror output was revitalized with the enormously successful Son of Frankenstein, in which the studio cast both stars (Lugosi and Karloff) again for the fourth time.

In November 1939, Universal Pictures released their last horror film of the 1930s with the historical and quasi-horror film, Tower of London. It stars Basil Rathbone as the future King Richard III of England, and Boris Karloff as his fictitious club-footed executioner Mord. Vincent Price, in only his third film, appears as George, Duke of Clarence. Tower of London is based on the traditional depiction of Richard rising to become King of England in 1483 by eliminating everyone ahead of him. Each time Richard accomplishes a murder, he removes one figurine from a dollhouse resembling a throne room. Once he has completed his task, he now needs to defeat the exiled Henry Tudor to retain the throne.

Other productions in the 1930s

Other studios followed Universal's lead. MGM's controversial Freaks (1932) frightened audiences at the time, featuring characters played by people who had real deformities. The studio even disowned the film, and it remained banned in the United Kingdom for 30 years.[67] Paramount Pictures' Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) is remembered for its innovative use of photographic filters to create Jekyll's transformation before the camera.[68] And RKO created the highly successful and influential monster movie, King Kong (1933). With the progression of the genre, actors like Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi were beginning to build entire careers in horror.

Also, early in the decade, Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer created the horror fantasy film Vampyr (1932) based on elements from J. Sheridan Le Fanu's collection of supernatural stories In a Glass Darkly. The German-produced sound film tells the story of Allan Gray, a student of the occult who enters a village under the curse of a vampire. According to the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, Vampyr's "greatness derives partly from Dreyer's handling of the vampire theme in terms of sexuality and eroticism, and partly from its highly distinctive, dreamy look."

1940s

The Wolf Man and Universal Classic Monsters sequels

Despite the success of The Wolf Man, by the 1940s, Universal's monster movie formula was growing stale, as evidenced by desperate sequels and ensemble films with multiple monsters. Eventually, the studio resorted to comedy-horror pairings, like Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, which was met with some success.[69] In the 1940s, Universal Pictures released 17 feature films, all of which were sequels or reboots to their popular monster movies from the late 20s and 30s.

In 1940, Universal Pictures released three movies. In January, The Invisible Man Returns, which stars Vincent Price, premiered in theaters to commercial success despite its production being plagued with problems.[70] The special effects in the movie received an Oscar nomination in the category Best Special Effects.

In September, The Mummy's Hand was released. Although it is sometimes claimed by fans as a sequel to The Mummy (1932), it does not continue that film's storyline, or feature any of the same characters. The Mummy's Hand was the first of a series of four films all featuring the mummy named Kharis. The sequels are The Mummy's Tomb (1942), The Mummy's Ghost, and The Mummy's Curse (both 1944). Tom Tyler played Kharis in the first installment but Lon Chaney, Jr. took over the role for the three sequels. Upon the film's release, film critic Bosley Crowther wrote for The New York Times, "It's the usual mumbo-jumbo of secret tombs in crumbling temples and salacious old high priests guarding them against the incursions of an archaeological expedition".[71]

In December, The Invisible Woman was released. It is the third film in the Invisible Man film series. This film was more of a screwball comedy than the other films in the series. The film stars Virginia Bruce in the lead role and John Barrymore in a supporting role. Reviews from critics were mixed. Theodore Strauss of The New York Times called it "silly, banal and repetitious".[72] Two more films from the Invisible Man series would be released in the decade. The propaganda war-horror Invisible Agent (1942), which featured a mad scientist working in secret to aid the Third Reich, and The Invisible Man's Revenge (1944).

Other notable sequels during this era include The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Son of Dracula (1943), and She-Wolf of London (1946).

In 1941, Universal Pictures released a reboot to the studio's 1935 werewolf picture Werewolf of London which starred Henry Hull in a more subtle werewolf makeup. The Wolf Man (1941), however, was more popular and influential in the genre. The character of Larry Talbot (aka The Wolf Man) is considered one of the best classic monsters in the series. The title character has had a great deal of influence on Hollywood's depictions of the legend of the werewolf.[73] He was portrayed by Lon Chaney Jr. in the 1941 picture and in the four sequels, all of which were released in the 1940s, including Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) and House of Dracula (1945), the latter of which Larry Talbot and Dracula seek a cure for their respective afflictions.

Other productions in the 1940s

In the 1940s, Val Lewton became a well known figure in early B-movie cinema for making low-budget films for RKO Pictures, including Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943), The Leopard Man (1943), which was directed by Jacques Tourneur, and The Body Snatcher (1945). The Body Snatcher was selected by the United States' National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". The decade also saw the continuation of Universal Pictures' consistent releases of horror, suspense and science fiction films. Lon Chaney Jr. became the studio's leading monster movie actor in the 1940s.

Paramount Pictures also released horror films in the 1940s, the most popular of which is The Uninvited (1944). The film has been noted by contemporary film scholars as being the first film in history to portray ghosts as legitimate entities, rather than illusions or misunderstandings played for comedy. It depicts various supernatural phenomena, including disembodied voices, apparitions, and possession. MGM's best known horror film of the decade is Albert Lewin's existential horror The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), which became popular for its use of color insert to show Dorian's haunting corrupted portrait.

In 1941, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released its own version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, starring Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman, and Lana Turner.

In 1945, Great Britain contributed the anthology horror film Dead of Night. In the film, house guests tell five supernatural tales, the last of which being the most remembered. The film's last story, titled The Ventriloquist's Dummy, features a ventriloquist tormented by a malevolent puppet.

Horror pictures of the 1940s crossed over with other popular film genres of the decade, including film noir, melodrama and mystery. Some of these movies include The Spiral Staircase (1946), which tells the story of a serial killer targeting women with afflictions, The Seventh Victim (1943), a horror/film noir story of a woman stumbling upon a Satanic cult while looking for her missing sister, and John Brahm's The Lodger (1944), where a landlady suspects her new lodger to be Jack the Ripper. A Finnish film The Green Chamber of Linnais (1945), directed by Valentin Vaala, presents romance and horror in an escapist way.[74]

The Queen of Spades (1949) is a fantasy/horror film about an elderly countess who strikes a bargain with the devil and exchanges her soul for the ability to always win at cards. Wes Anderson ranked it as the sixth best British film.[75] Martin Scorsese said that The Queen of Spades is a "stunning film" and one of "the few true classics of supernatural cinema."[76] And Dennis Schwartz of Ozus' World Movie Reviews called it "A masterfully filmed surreal atmospheric supernatural tale".[77]

1950s

With advances in technology, the tone of horror films shifted from Gothic tones to contemporary concerns. A popular horror subgenre began to emerge: the Doomsday film.[78] Low-budget productions featured humanity overcoming threats such as alien invasions and deadly mutations to people, plants, and insects. Popular films of this genre include Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and The Blob (1958).

The science fiction horror film Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) follows an extraterrestrial invasion where aliens are capable of reproducing a duplicate replacement copy of each human. It is considered to be the most popular and most paranoid film from the golden age of American sci-fi cinema.

The arrival of 3-D

In the 1950s, television had arrived and the theatrical market was changing. Producers and exhibitors found new, exciting and enticing ways to keep audiences in theaters. This is how Hollywood directors and producers found ample opportunity for audience exploitation through gimmicks. The years 1952 through 1954 are considered the "Golden Era" of 3-D movies. In a three-dimensional stereoscopic film, the audience's brains are tricked into believing the images projected onto a flat cinema screen are coming to life in full three-dimensional glory.[79] Through this way, the audience's fright factor is enhanced. Those who came to see a 3-D movie inside a theater were given the familiar disposable cardboard anaglyph 3D glasses to wear which will allow them to see the images come to life.

In April 1953, Warner Bros. presented the horror-thriller House of Wax, the first 3D feature with stereophonic sound. The film, which stars Vincent Price, tells a story of a disfigured sculptor who repopulates his destroyed wax museum by murdering people and using their wax-coated corpses as displays. House of Wax was the film that typecast Price as a horror icon. A year later, he played a trademark role as a round-the-bend illusionist bent on revenge in the 3D film noir The Mad Magician (1954). After the release of that film, Price would be labeled the "King of 3-D" and would later become the actor to star in the most 3D features. The success of these two films proved that major studios now had a method of getting film-goers back into theaters and away from television sets, which were causing a steady decline in attendance.

William Castle and promotional gimmicks in theaters

Aside from 3-D technology, different forms of promotional gimmicks were used to entice film-goers into seeing the films in theaters. One example was during the screening of The Lost Missile (1958), a science fiction film in which scientists try to stop a mysterious missile from destroying the Earth. Audiences who saw the film in theaters were given "shock tags" to monitor their vitals during the movie. They were promised that anyone who would get shocked into a comatose state by the film would get a free ride home in a limousine.[80]

Film director and producer William Castle is considered the King of the gimmick. After directing a cavalcade of B-movies for Columbia Pictures in the 1940s, Castle set out on the independent route. To help sell his first self-financed film Macabre (1958), he not only hired girls to stand in as fake nurses outside theater doors in case anyone needed medical attention, he also passed out a certificate for a $1,000 life insurance policy to each member of the audience in case anyone would happen to die of fright from watching his film. This kind of promotional gimmick would later make him famous.[81] Another gimmick Castle utilized in his films was EMERGO, which was used during the screening of his cult classic House on Haunted Hill (1959), which also starred Vincent Price. Throughout the promotion of this film, Castle explained that through EMERGO, "ghosts and skeletons leave the screen and wander throughout the audience, roam around and go back to the screen". Of course, in actuality, a skeleton with glowing red eyes was attached to wires above the theater screen in order to swoop in and float above audience members' heads to parallel the action on the screen.[82] Another Castle/Price production was The Tingler (1959) which tells the story of a scientist who discovers a parasite in human beings, called a "tingler", which feeds on fear. In the film, Price breaks the fourth wall and warns the audience that the tingler is in the theater, which then prompts the built-in electric buzzers to scare audiences in their theater seats.

Creature features

The 1950s is also well known for creature features or giant monster movies. These are usually disaster films that focus on a group of characters struggling to survive attacks by one or more antagonistic monsters, often abnormally large ones. The monster is often created by a folly of mankind – an experiment gone wrong, the effects of radiation or the destruction of habitat. Sometimes the monster is from outer space, has been on Earth for a long time with no one ever seeing it, or released from a prison of some sort where it was being held. In monster movies, the monster is usually a villain, but can be a metaphor of humankind's continuous destruction. Warner Bros.' The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) is considered to be the film which kick-started the 1950s wave of monster movies and the concept of combining nuclear paranoia with the genre.[83] In the film, a beast was awakened from its hibernating state in the frozen ice of the Arctic Circle by an atomic bomb test. It then begins to wreak a path of destruction as it travels southward, eventually arriving at its ancient spawning grounds, which includes New York City. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was the first ever live-action film to feature a giant monster awakened, preceding Godzilla (1954) by 16 months. The film is also remembered for its influential stop motion model animation created by visual effects creator Ray Harryhausen.

Ray Harryhausen created his own form of stop motion model animation called Dynamation. It involved photographing a miniature against a rear-projection screen through a partly masked pane of glass. The masked portion would then be re-exposed to insert foreground elements from the live footage. The effect was to make the creature appear to move in the midst of live action. It could now be seen walking behind a live tree, or be viewed in the middle distance over the shoulder of a live actor – effects difficult to achieve before.[84] The first movie to have the Dynamation label was the fantasy adventure film The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). In the movie, a princess is shrunken by an evil wizard. Sinbad must undertake a quest to an island of monsters to cure her and prevent a war. It took Harryhausen 11 months to complete the full color, widescreen stop-motion animation sequences for the movie. The film features a few creatures including a cyclops, a cobra-woman, a dragon, and a fighting skeleton. The sword fight scene between Sinbad and the skeleton proved so popular with audiences that Harryhausen recreated and expanded the scene five years later, this time having a group of seven armed skeletons fight the Greek hero Jason and his men in 1963's Jason and the Argonauts.[85]

Harryhausen's innovative style of special effects inspired numerous filmmakers including future directors Peter Jackson, Tim Burton, and Guillermo del Toro.[86] In the fantasy film Jason and the Argonauts (1963), there is an iconic fight scene that involves skeleton warriors. That scene spurred on numerous homages in many horror films[87] including A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987), Army of Darkness (1992), and a season 4 episode of Game of Thrones (2014) entitled The Children.[88]

Other notable creature films from the 50s include It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), Tarantula (1955), and The Giant Behemoth (1959). Another well-known movie in this decade was Night of the Demon (1957).

Japan's experience with Hiroshima and Nagasaki bored the well-known Godzilla (1954) and its many sequels, featuring mutation from the effects of nuclear radiation. This kickstarted the tokusatsu trend known as Kaiju films, a Japanese film genre that features giant monsters, usually attacking major cities and engaging the military and other monsters in battle. Other films in this genre include Rodan (1956) and The Mysterians (1957). Besides Kaiju films, Japan was also into ghost cat/feline ghost movies in the 1950s. These include Ghost-Cat of Gojusan-Tsugi (1956), and Black Cat Mansion (1958), which tells a story of a samurai tormented by a cat possessed by the spirits of the people she killed.

Science fiction and horror in the 1950s

Filmmakers continued to merge elements of science fiction and horror over the following decades. The Fly (1958) is an American science fiction horror film starring Vincent Price, and tells the story of a scientist who is transformed into a grotesque creature after a house fly enters into a molecular transporter he is experimenting with, resulting in his atoms being combined with those of the insect, which produces a human-fly hybrid. The film was released in CinemaScope with Color by 20th Century Fox. It was followed by two black-and-white sequels, Return of the Fly (1959) and Curse of the Fly (1965). The original film was remade in 1986 by director David Cronenberg.

Considered a "pulp masterpiece"[89] of the 1950s was The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), based on Richard Matheson's existentialist novel. The film tells the story of a man, who after getting exposed to a radioactive cloud, gets shrunk in height by several inches. The film conveyed the fears of living in the Atomic Age and the terror of social alienation. It won the first Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and was chosen for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically or aesthetically" significant.

An independently produced sci-fi film Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) tells the story of a wealthy heiress whose close encounter with an enormous alien causes her to grow into a giantess, complicating her marriage already troubled by a philandering husband. The film has become a cult classic and is often referenced in popular culture. It is also a variation on other 1950s science fiction films that featured size-changing humans, including The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), and its sequel War of the Colossal Beast (1958).

Hammer Films

The United Kingdom began to emerge as a major producer of horror films around this time.[92] The Hammer company focused on the genre for the first time, enjoying huge international success from films involving classic horror characters, which were shown in color for the first time.[93] Drawing on Universal's precedent, many films produced were Frankenstein and Dracula remakes, followed by many sequels. Christopher Lee starred in a number of Hammer horror films, including The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), which Professor Patricia MacCormac called the "first really gory horror film, showing blood and guts in colour".[94] His most influential role was as Count Dracula, with the portrayal becoming the archetypal vampire in popular culture. The academic Christopher Frayling writes that Lee's film, Dracula (1958), introduced fangs, red contact lenses, décolletage, ready-prepared wooden stakes and – in the celebrated credits sequence – blood being spattered from off-screen over the Count's coffin."[95] Lee also introduced a dark, brooding sexuality to the character, with Tim Stanley stating, "Lee’s sensuality was subversive in that it hinted that women might quite like having their neck chewed on by a stud".[96] Other British companies contributed to the horror genre in the 1960s and 1970s.

Universal Classic Monsters in the 1950s

Universal Pictures released the last of their horror films in the 1950's. They continued releasing commercially-successful movies with the horror-comedy parodies starring the comedy duo Abbott and Costello, and a few monster movies including the classic Creature from the Black Lagoon.

In March 1951, Universal Pictures premiered Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man. The science fiction comedy depicts the misadventures of two private detectives investigating the murder of a boxing promoter. The film was part of a series in which the legendary comedy duo Bud Abbott and Lou Costello meet classic characters from Universal's stable, including Frankenstein, the Mummy and the Keystone Kops. The special effects in the movie, which depicted invisibility and other optical illusions, were created by Stanley Horsley, son of cinema pioneer David Horsley.

In February 1954, Creature from the Black Lagoon premiered in theaters in 3-D. The film was so popular, it generated two sequels: Revenge of the Creature (1955), and The Creature Walks Among Us (1956). The Creature, also known as the Gill-man, is usually counted among the classic Universal Monsters.

Horror anthology series in 1950s television

Horror has been a mainstay of television programming since the 1950s. The 2013 book TV Horror: Investigating the Dark Side of the Small Screen, observed that television has helped shape many generations of horror fans and filmmakers because it provided them their first exposure to cinematic horror as children cowering behind their sofa or peering out from under their blanket[97] In the 1950s, multiple anthology series that feature suspenseful horror stories were broadcast on television. The Veil (1958) is one notable anthology series that starred Boris Karloff as the horror host and characters in the episodes. 10 of the 12 episodes begin and end with Karloff standing in front of a roaring fireplace and inviting viewers to find out what lies "behind the veil". Hailed by critics as "the greatest television series never seen", The Veil was not broadcast. Troubles within the studio resulted in production being cancelled after 10 episodes were produced. The number of episodes was considered to be too small to justify sale to a network or to syndication. The ten episodes were released to the public in their entirety for the first time in the 1990s, and have subsequently been released on DVD by Something Weird Video.[98]

Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955–1965) premiered in October 1955, which featured dramas, thrillers, mysteries, horror and crime. It was created, hosted, and produced by Alfred Hitchcock, who by 1955 had already directed films for over three decades. Some of the stories in the show were original, while others were adaptations of writers like H. G. Wells, and always had knotty twists and often came to macabre endings, as in the 4 December 1955 episode "The Case of Mr. Pelham," in which a businessman is stalked by a perfect double who usurps his life and drives him insane. Time magazine named the series as one of "The 100 Best TV Shows of All Time".[99]

The Twilight Zone (1959–1964) has become a staple in horror fiction since its premiere in October 1959.[100] Each episode presents a standalone story in which characters find themselves dealing with disturbing or unusual events, an experience described as entering "the Twilight Zone". Although predominantly science-fiction, the show's paranormal and Kafkaesque events leaned the show towards fantasy and horror. The phrase "twilight zone," is used today to describe surreal experiences. An iconic episode which premiered on 20 November 1959 is Time Enough at Last which tells the story of a bank teller who yearns for more time to read and gets his wish when he becomes the sole survivor of a nuclear holocaust. In 2009, TV Guide ranked this episode #11 on its list of the 100 Greatest Episodes.

Other notable horror anthologies in the 50s include The Vampira Show (1954–1955), which was presented by Maila Nurmi, considered to be television's first horror host, dressed as her iconic campy Vampira character, and 13 Demon Street (1959–1960), which was hosted by Lon Chaney Jr. who, as a condemned criminal, introduces crime stories to convince viewers that the crimes presented are worse than his.

1960s

Roger Corman's Edgar Allan Poe cycle

In the early 1960s, the production company American International Pictures, or AIP, gained popularity by combining Roger Corman, Vincent Price and the stories of Edgar Allan Poe into a series of horror films, with scripts by Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Ray Russell, R. Wright Campbell and Robert Towne.

The original idea, usually credited[who?] to Corman and Lou Rusoff, was to take Poe's story "The Fall of the House of Usher", which had both a high name-recognition value and the merit of being in the public domain, and thus royalty-free, and expand it into a feature film. Corman convinced the studio to give him a larger budget than the typical AIP film so he could film the movie in widescreen and color, and use it to create lavish sets as well.[101]

The success of House of Usher led AIP to finance further films based on Poe's stories. The sets and special effects were often reused in subsequent movies (for example, the burning roof of the Usher mansion reappears in most of the other films as stock footage), making the series quite cost-effective. All the films in the series were directed by Roger Corman, and they all starred Price except The Premature Burial, which featured Ray Milland in the lead. It was originally produced for another studio, but AIP acquired the rights to it.[101]

As the series progressed, Corman made attempts to change the formula. Later films added more humor to the stories, especially The Raven, which takes Poe's poem as an inspiration and develops it into an all-out farce starring Price, Boris Karloff and Peter Lorre; Karloff had starred in a 1935 film with the same title. Corman also adapted H. P. Lovecraft's short novel The Case of Charles Dexter Ward in an attempt to get away from Poe, but AIP changed the title to that of an obscure Poe poem, The Haunted Palace, and marketed it as yet another movie in the series. The last two films in the series, The Masque of the Red Death and The Tomb of Ligeia, were filmed in England with an unusually long schedule for Corman and AIP.

Although Corman and Rusoff are generally credited with coming up with the idea for the Poe series, in an interview on the Anchor Bay DVD of Mario Bava's Black Sabbath, Mark Damon claims that he first suggested the idea to Corman. Damon also says that Corman let him direct The Pit and the Pendulum uncredited. Corman's commentary for Pit mentions nothing of this and all existing production stills of the film show Corman directing.

List of Corman-Poe films

Of eight films, seven feature stories that are actually based on the works of Poe.

- House of Usher (1960) – based on the short story "The Fall of the House of Usher"

- The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) – based on the title of the short story of the same name

- The Premature Burial (1962) – based on the short story of the same name

- Tales of Terror (1962) – based on the short stories "Morella", "The Black Cat", "The Cask of Amontillado" and "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar"

- The Raven (1963) – based on the poem of the same name

- The Haunted Palace (1963) – based on H.P. Lovecraft's novella The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, using the title from Poe's 1839 poem

- The Masque of the Red Death (1964) – based on the short story of the same name with another Poe short story, "Hop-Frog", used as a subplot

- The Tomb of Ligeia (1964) – based on the short story "Ligeia"

Occasionally, Corman's 1963 film The Terror (produced immediately after The Raven) is recognized as being part of the Corman-Poe cycle, although the film's story and title are not based on any literary work of Poe.

Based in rented office space at the Chaplin Studios, during the early 1960s AIP concentrated on horror films inspired by the Poe cycle.

Other productions in the 1960s

Released in May 1960, the British psychological horror thriller film, Peeping Tom (1960) by Michael Powell, is a progenitor of the contemporary "slasher film",[102] though Alfred Hitchcock cemented the subgenre with Psycho released also in the same year.[103] Hitchcock, considered to be the "Master of Suspense" didn't set out to frighten fans the way many other traditional horror filmmakers do. Instead, he helped pioneer the art of psychological suspense. As a result, he managed to frighten his viewers by getting to the root of their deepest fears.[104] One of his most frightening films besides Psycho is The Birds (1963), where a seemingly idyllic town is overrun by violent birds.

France continued the mad scientist theme with the film Eyes Without a Face (1960). The story follows Parisian police in search of the culprit responsible for the deaths of young women whose faces have been mutilated.[105] In Criterion's description of the film, they say it include "images of terror, of gore, [and] of inexplicable beauty".[106]

Meanwhile, Italian horror films became internationally notable thanks to Mario Bava's contributions. His film La Maschera del Demonio (1960), marketed in English as The Mask of Satan then wound up being known as Black Sunday in the United States and Revenge of the Vampire in the United Kingdom. In this film, Bava turned a Russian folk legend into a beguiling fairly tale about a young doctor who finds himself stranded in a haunted community and falls for a woman whose body become possessed by a woman executed for witchcraft. Three years later, Bava went on to make the horror anthology film Black Sabbath (1963) known in Italy as I tre volti della paura, literally 'The Three Faces of Fear'.