The Babadook

| The Babadook | |

|---|---|

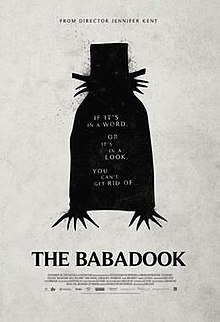

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jennifer Kent |

| Screenplay by | Jennifer Kent |

| Based on | Monster by Jennifer Kent |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Radek Ładczuk |

| Edited by | Simon Njoo |

| Music by | Jed Kurzel |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 94 minutes[1] |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million |

| Box office | $10.3 million[2] |

The Babadook is a 2014 Australian psychological horror film written and directed by Jennifer Kent in her directorial debut,[3] and produced by Kristina Ceyton and Kristian Moliere. The film stars Essie Davis, Noah Wiseman, Daniel Henshall, Hayley McElhinney, Barbara West, and Ben Winspear. It is based on Kent's 2005 short film Monster.

The film premiered at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival on 17 January,[4][5] and generated attention and critical acclaim in the United States and Europe, grossing $10.3 million against a $2 million budget. The Babadook was initially not a commercial success in Australia and was given a limited release in art house cinemas, beginning on 22 May 2014.[6]

Plot[]

Amelia Vakan is a troubled and exhausted widow living in the Australian city of Adelaide, who has brought up her six-year-old son Samuel alone. Her late husband, Oskar, was killed in a car accident that occurred as he drove Amelia to the hospital during labour. Sam begins displaying erratic behaviour: he becomes an insomniac and is preoccupied with an imaginary monster, against which he has built weapons to fight. Amelia is forced to pick up her son from school after Sam brings one of the weapons there. One night, Sam asks his mother to read a pop-up storybook called Mister Babadook. It describes the titular monster, the Babadook, a tall pale-faced humanoid in a top hat with taloned fingers which torments its victims after they become aware of its existence. Amelia is disturbed by the book and its mysterious appearance, while Sam becomes convinced that the Babadook is real. Sam's persistence about the Babadook leads Amelia to often have sleepless nights as she tries to comfort him.

Soon after, strange events occur: doors open and close mysteriously by themselves, strange sounds are heard and Amelia finds glass shards in her food. She attributes the events to Sam's behaviour, but he blames the Babadook. Amelia rips up the book and disposes of it. At her birthday party, Sam's cousin Ruby bullies Sam for not having a father, in response to which he pushes her out of her tree house; as a result she breaks her nose. Amelia's sister Claire admits she cannot bear Sam, to which Amelia takes great offence. On the drive home, Sam has another vision of the Babadook and suffers a seizure, so Amelia gets some sedatives from a paediatrician.

The following morning, Amelia finds the Mister Babadook book reassembled on the front door step. New words taunt her by saying that the Babadook will become stronger if she continues to deny its existence, containing pop-ups of her killing their dog Bugsy, Sam, and then herself. Terrified, Amelia burns the book and runs to the police station after a disturbing phone call. However, Amelia has no proof of the stalking, and when she then sees the Babadook's suit hung up behind the front desk, she leaves. Amelia starts to become more isolated and shut-in, becoming impatient, shouting at Samuel for 'disobeying' her constantly, and having frequent visions of the Babadook once again. Her mental state slowly decays and she exhibits erratic and violent behaviour, including cutting the phone line with a knife and then waving the same knife aggressively at Sam without realizing it. This devolves into disturbing hallucinations, where Amelia violently murders Sam.

Shortly after these visions, Amelia sees an apparition of Oskar, who offers to return to her if she "brings the boy" to him. Realizing that he is a creation of the Babadook, Amelia flees and is stalked through the house by the Babadook until it finally possesses her. Under its influence she breaks Bugsy's neck and attempts to kill Sam. Eventually luring her into the basement, Sam knocks her out. Tied up, Amelia awakens with Sam, terrified, nearby. When she tries to strangle him, he lovingly caresses her face, causing her to regurgitate an inky black substance, which seemingly expels the Babadook. When Sam reminds Amelia that "you can't get rid of the Babadook," an unseen force drags him into Amelia's bedroom. After saving Sam, Amelia is forced by the Babadook to re-watch a vision of her husband's death. Furious, she confronts the Babadook, making the beast retreat into the basement, and she locks the door behind it.

After this ordeal, Amelia and Sam manage to recover. Amelia is attentive and caring toward him, encouraging him toward the weapons he makes and being impressed at Sam's magic tricks. They gather earthworms in a bowl, and Amelia takes them to the basement, where the Babadook resides. She places the bowl on the floor for the Babadook to eat. However, as the beast tries to attack her, Amelia calms it down, and it retreats to the corner, taking the earthworms with it. Amelia returns to the yard to celebrate Sam's birthday.

Cast[]

- Essie Davis as Amelia Vanek

- Noah Wiseman as Samuel Vanek

- Hayley McElhinney as Claire

- Daniel Henshall as Robbie

- Barbara West as Gracie Roach

- Ben Winspear as Oskar Vanek

- Cathy Adamek as Prue Flannery

- Craig Behenna as Warren Newton

- Chloe Hurn as Ruby

- Jacquy Phillips as Beverly

- Bridget Walters as Norma

- Adam Morgan as Sergeant

- Charlie Holtz as Kid No. 2

- Tim Purcell as the Babadook

- Hachi as Bugsy

Production[]

Development[]

Kent studied at the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA), where she learned acting alongside Davis, and graduated in 1991.[7] She then worked primarily as an actor in the film industry for over two decades. Kent eventually lost her passion for acting by the end of the 1990s and sent a written proposal to Danish filmmaker Lars von Trier, asking if she could assist on the film set of von Trier's 2003 drama film, Dogville, to learn from the director. Kent's proposal was accepted and she considers the experience her film school, citing the importance of stubbornness as the key lesson she learned.[8][9]

Prior to Babadook, Kent's first feature film, she had completed a short film, titled Monster, and an episode of the television series Two Twisted. Kent explained in May 2014 that the origins of Babadook can be found in Monster, which she calls "baby Babadook".[10]

The writing of the screenplay began in around 2009 and Kent has stated that she sought to tell a story about facing up to the darkness within ourselves, the "fear of going mad" and an exploration of parenting from a "real perspective". In regard to parenting, Kent further explained in October 2014: "Now, I'm not saying we all want to go and kill our kids, but a lot of women struggle. And it is a very taboo subject, to say that motherhood is anything but a perfect experience for women."[8] In terms of the characters, Kent said that it was important that both characters are loving and lovable, so that "we [audience] really feel for them"—Kent wanted to portray human relationships in a positive light.[8] In total, Kent completed five drafts of the script.[11]

Kent drew from her experience on the set of Dogville for the assembling of her production team, as she observed that von Trier was surrounded by a well-known "family of people". Therefore, Kent sought her own "family of collaborators to work with for the long term." Unable to find all of the suitable people within the Australian film industry, Kent hired Polish director of photography (DOP) Radek Ladczuk, for whom Babadook was his first-ever English language film, and American illustrator Alexander Juhasz.[10] In terms of film influences, Kent cited 1960s, '70s and '80s horror—including The Thing (1982), Halloween (1978), Les Yeux Sans Visage (1960), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Carnival of Souls (1962) and The Shining (1980)—as well as Vampyr (1932), Nosferatu (1922) and Let The Right One In (2008).[12]

Although the process was challenging and she was forced to reduce their total budget, producer Kristina Ceyton managed to secure funding of around A$2.5 million from government bodies Screen Australia and the SAFC; however, they still required an additional budget for the construction of the film sets. To attain the funds for the sets, Kent and Causeway Films producer Kristina Ceyton launched a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign in June 2012, with a target of US$30,000. Their funding goal was reached on 27 September 2012 through pledges from 259 backers raising $30,071.[13][14]

Filming[]

The film was primarily shot in Adelaide, South Australia, with most of the interior shots filmed on a sound stage in the city; as funding was from the South Australian state government, this was a requirement that Kent needed to meet.[7] However, Kent explained to the Den of Geek website that she is not patriotic and didn't want the film to be "particularly Australian".

I wanted to create a myth in a domestic setting. And even though it happened to be in some strange suburb in Australia somewhere, it could have been anywhere. I guess part of that is creating a world that wasn't particularly Australian ... I'm very happy, actually, that it doesn't feel particularly Australian.

Director Jennifer Kent on her desire to avoid the clichéd "Australian feel" of the film[8]

To contribute to the universality of the film's appearance, a Victorian terrace-style house was specifically built for the film, as there are very few houses designed in such a style in Adelaide.[8] A script reading was not done due to Noah Wiseman's age at the time, six years old, and Kent focused on bonding, playing games and lots of time spent with the actors in which they became more familiar with one another. Pre-production occurred in Adelaide and lasted three weeks and, during this time, Kent conveyed a "kiddie" version of the narrative to Wiseman.[11]

Kent originally wanted to film solely in black-and-white, as she wanted to create a "heightened feel" that is still believable. She was also influenced by pre-1950s B-grade horror films, as it was "very theatrical", in addition to being "visually beautiful and terrifying". Kent later lost interest in the black-and-white idea and worked closely with production designer Alex Holmes and Radek to create a "very cool", "very claustrophobic" interior environment with "meticulously designed" sets.[8][10] The film's final colour scheme was achieved without the use of gels on the camera lenses or any alterations during the post-filming stage.[9] Kent cited filmmakers David Lynch and Roman Polanski as key influences during the filming stage.[11]

Kent described the filming process as "stressful" because of Wiseman's age. Kent explained "So I really had to be focused. We needed double the time we had." Wiseman's mother was on set and a "very protective, loving environment" was created.[8] Kent explained after the release of the film that Wiseman was protected throughout the entire project: "During the reverse shots where Amelia was abusing Sam verbally, we had Essie [Davis] yell at an adult stand-in on his knees. I didn't want to destroy a childhood to make this film—that wouldn't be fair."[11] Kent's friendship with Davis was a boon during filming and Kent praised her former classmate in the media: "To her credit, she's [Davis] very receptive, likes to be directed and is a joy to work with."[10]

In terms of the Babadook monster and the scary effects of the film, Kent was adamant from the outset of production that a low-fi and handmade approach would be used. She cites the influence of Georges Méliès, Jean Epstein's The Fall of the House of Usher and Häxan.[15] Kent used stop-motion effects for the monster and a large amount of smoothening was completed in post-production. Kent explained to the Empire publication: "There's been some criticism of the lo-fi approach of the effects, and that makes me laugh because it was always intentional. I wanted the film to be all in camera."[12] She has also said that The Man in the Beaver Hat from the 1927 lost film London After Midnight was an inspiration for the design of the Babadook.[16]

Music[]

The soundtrack was composed by Jed Kurzel, who also composed the soundtrack for Alien: Covenant. released the album on vinyl in 2017.[17]

Release[]

The film's global premiere was in January 2014 at the Sundance Film Festival. The film then received a limited theatrical release in Australia in May 2014,[11] following a screening in April 2014 at the Stanley Film Festival.[18]

In Singapore, the film was released on 25 September 2014.[7] The film opened in the United Kingdom for general release on 17 October 2014, and in the United States on 28 November 2014.[11]

Home media[]

The film, alongside the short film Monster, was first released on DVD and Blu-ray in Australia by Umbrella Entertainment on 31 October 2014.[19] The U.S. Blu-ray and DVD was released on 14 April 2015 by IFC Midnight and Scream Factory, and the special edition was also available on that date.[20][21] The special edition features Kent's short film, Monster, and the comic novel, Creating the Book, by Juhasz.[22] The UK Blu-ray Disc features the short documentary films Illustrating Evil: Creating the Book, There's No Place Like Home: Creating the House and Special Effects: The Stabbing Scene.[23]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The Babadook opened in Australia on 22 May 2014 in just 13 cinemas on a limited release, eventually grossing a total of only $258,000.[24] The film fared much better internationally than it did in its native country. In North America, The Babadook opened on a limited release basis in three theaters and grossed US$30,007, with an average of $10,002 per theater. The film ranked in the 42nd position at the box office, and, as of 1 February 2015, has grossed $964,413 in the U.S. and $9.9 million elsewhere in the world. To date, the film's worldwide box office takings are $10.3 million which compares favourably with the estimated production budget of $2 million.[25] It was subsequently released in France, where it opened at number 11 at the French box office. Its success overseas re-generated interest in Australia, and the film was expanded to mainstream movie-theatres like Event, rather than primarily art house cinemas.

Critical response[]

The Babadook was one of the best reviewed films of 2014. It holds an approval rating of 98% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 241 reviews, with an average rating of 8.2/10. The critical consensus states: "The Babadook relies on real horror rather than cheap jump scares—and boasts a heartfelt, genuinely moving story to boot."[26] The film also has a score of 86 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 34 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[27] On Rotten Tomatoes' aggregation, it was ranked as the third most-praised film of the year.[28]

Glenn Kenny, writing for RogerEbert.com, called the film “the finest and most genuinely provocative horror movie to emerge in this still very-new century”.[29] Dan Schindel from Movie Mezzanine said that "The Babadook is the best genre creature creation since the big black wolf-dog aliens from Attack the Block."[30] After seeing the film at the 2014 Stanley Film Festival, Flay Otters wrote on the HorrorMovies.ca fan site: "This is a film that mixes strong-minded storytelling with a clear dedication to craft ... It is mature and patient and it is, without a doubt, one of the best horror films this year."[31]

On 30 November 2014, William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist (1973) stated on his Twitter profile, "Psycho, Alien, Diabolique, and now THE BABADOOK."[32] Friedkin also added, "I've never seen a more terrifying film. It will scare the hell out of you as it did me."[33] Prominent British film critic Mark Kermode named The Babadook his favourite film of 2014[34] and in 2018 listed it his eighth favourite film of the decade.[35]

Film scholar Amanda Howell argues that part of the film's critical success can be attributed to many film critics having discussed the film within the context of art-horror rather than purely as a horror film. Howell discussed the film as part of an international cycle of contemporary art-horror films alongside Pan's Labyrinth (2006), Let the Right One In (2008) and Antichrist (2009) that negotiate and blur the boundaries between art and horror.[36]

Accolades[]

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th AACTA Awards | Best Film1[37] | Kristina Ceyton Kristian Molière |

Won |

| Best Direction | Jennifer Kent | Won | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Won | ||

| Best Actress | Essie Davis | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Simon Njoo | Nominated | |

| Best Production Design | Alex Holmes | Nominated | |

| 4th AACTA International Awards[38] | Best Actress | Essie Davis | Nominated |

| Critics' Choice Award | Best Sci-Fi/Horror Movie | The Babadook | Nominated |

| Best Young Actor | Noah Wiseman | Nominated | |

| Detroit Film Critics Society Awards | Best Actress | Essie Davis | Nominated |

| Best Breakthrough | Jennifer Kent | Nominated | |

| 20th Empire Awards | Best Female Newcomer | Essie Davis | Nominated |

| Best Horror | The Babadook | Won | |

| Fangoria Chainsaw Awards | Best Limited-Release/Direct-to-Video Film | Jennifer Kent | Won |

| Best Screenplay | Won | ||

| Best Actress | Essie Davis | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Noah Wiseman | Won | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best First Feature | Kristina Ceyton Kristian Molière |

Won |

| Online Film Critics Society Awards | Best Actress | Essie Davis | Nominated |

| San Francisco Film Critics Circle Award | Best Actress | Nominated | |

| 41st Saturn Awards | Best Horror Film | Kristina Ceyton Kristian Molière |

Nominated |

| Best Actress | Essie Davis | Nominated | |

| Best Performance by a Younger Actor | Noah Wiseman | Nominated |

1 Shared award with The Water Diviner

LGBT community[]

In October 2016, a Tumblr user joked that the Babadook is openly gay; in December 2016, another Tumblr user posted a viral screenshot showing the movie classified by Netflix as an LGBT film.[39][40] Despite the absence of overt references to LGBT culture in the film, fans and journalists generated interpretations of queer subtext in the film that were often tongue-in-cheek, but occasionally more serious, highlighting the character's dramatic persona, grotesque costume, and chaotic effect within a traditional family structure. In June 2017, The Babadook trended on Twitter and was displayed as a symbol during that year's Pride Month.[41] The social media response became so strong that theatres in Los Angeles took the opportunity to hold screenings of the film for charity.[42]

Jennifer Kent said she "loved" the meme, saying that "I think it's crazy and [the meme] just kept him alive. I thought ah, you bastard. He doesn't want to die so he's finding ways to become relevant."[43]

Themes and symbolism[]

Writing for The Daily Beast, Tim Teeman contends that grief is the "real monster" in The Babadook, and that the film is "about the aftermath of death; how its remnants destroy long after the dead body has been buried or burned". Teeman writes that he was "gripped" by the "metaphorical imperative" of Kent's film, with the Babadook monster representing "the shape of grief: all-enveloping, shape-shifting, black". Teeman states that the film's ending "underscored the thrum of grief and loss at the movie's heart", and concludes that it informs the audience that grief has its place and the best that humans can do is "marshal it".[44]

Egyptian national film critic Wael Khairy wrote in his "Film Analysis" on 22 November 2014 that The Babadook "taps into something real, a real human fear".[45] Khairy argues that what the Babadook stands for is "up for debate", but writes:

The malevolent Babadook is basically a physicalised form of the mother's trauma ... I believe, the Babadook embodies the destructive power of grief. Throughout the film, we see the mother insist nobody bring up her husband's name. She basically lives in denial. Amelia has repressed grief for years, refusing to surrender to it.[45]

Khairy concluded that the film is "based on something very real" and "feels unusually beautiful and even therapeutic."[45]

Samuel displays some autistic traits and parents of autistic children have identified with themes in the film, including the social isolation and sleep deprivation that commonly overwhelm them.[46]

References[]

- ^ "The Babadook". British Board of Film Classification. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "The Babadook". The Numbers. The Numbers. 28 November 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ "SA film to make a profit thanks to overseas success". abc.net.au. 11 October 2014.

- ^ Caceda, Eden (9 December 2013). "Two Aussie Features Selected For Sundance". Filmink. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015.

- ^ Rooney, David (21 January 2014). "The Babadook: Sundance Review". .

- ^ "The Babadook's monster UK box office success highlights problems at home". The Guardian Australia. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ a b c John Lui (24 September 2014). "Director Jennifer Kent's debut feature The Babadook is a horror movie without gore or cheap screams". The Straits Times. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ryan Lamble (13 October 2014). "Jennifer Kent interview: directing The Babadook". Den Of Geek. Dennis Publishing Limited. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b Paul MacInnes (18 October 2014). "The Babadook: 'I wanted to talk about the need to face darkness in ourselves'". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d Sandy George (21 May 2014). "How Jennifer Kent made The Babadook". SBS. SBS. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Ethan Alter (14 November 2014). "Parental descent: Jennifer Kent's 'The Babadook' is a spooky tale of a mother in crisis". Film Journal International. Film Journal International. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b Helen O'Hara (2014). "The Scariest Film Of The Year? Jennifer Kent On The Babadook". Empire. Bauer Consumer Media Ltd. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Jennifer Kent, Kristina Ceyton (June 2012). "Realise the vision of The Babadook". Kickstarter. Kickstarter, Inc. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Jennifer Kent, Kristina Ceyton (June 2012). "The Babadook – Profile". Kickstarter. Kickstarter, Inc. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Gary Collinson (13 November 2014). "Interview with Jennifer Kent, director of The Babadoo". Flickering Myth. Flickering Myth. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Interview with The Babadook's Writer-Director Jennifer Kent". mountainx.com.

- ^ Ediriwira, Amar (2 March 2017). "Waxwork Records teases The Babadook soundtrack release with pop-up artwork". The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Shipra Gupta (3 April 2014). "Stanley Film Festival Announces Full Lineup". IndieWire. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Babadook, The (Blu Ray)". Umbrella Entertainment. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ John Lui (24 September 2014). "Scream Factory and IFC Midnight Teaming for The Babadook Home Video Release". The Straits Times. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ John Lui (24 September 2014). "'The Babadook' Comes Knockin' On Scream Factory's Door". The Straits Times. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ John Lui (24 September 2014). "'The Babadook' Gets Special Edition Release!". The Straits Times. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ John Lui (24 September 2014). "'The Babadook' Gets Special Edition Release!". The Straits Times. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Why was 'The Babadook' kept from Australians". The New Daily. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ "The Babadook". Box Office Mojo. IMDb.com, Inc. 1 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "The Babadook". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "The Babadook". Metacritic. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ "Best of 2014". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Glenn's Kenny (28 November 2014). "The Babadook Movie Review [Stanley Film Festival]". RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Schindel, Dan (22 January 2014). "Sundance Review: The Babadook Scares and Surprises". Movie Mezzanine. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Flay Otters (26 April 2014). "The Babadook Movie Review [Stanley Film Festival]". HorrorMovies.ca. HorrorMovies.ca. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "6:29 PM – 30 Nov 2014". William Friedkin on Twitter. Twitter. 30 November 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "6:14 PM – 30 Nov 2014". William Friedkin on Twitter. Twitter. 30 November 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ My Top Ten Films of 2014 - Part 2. Youtube. 30 December 2014. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Kermode Uncut: My Top Ten Films Of The Last Ten Years - Part One, archived from the original on 17 November 2021, retrieved 12 June 2021

- ^ Howell, Amanda. 2017. Haunted Art House: The Babadook and International Art Cinema Horror. In Ryan, Mark David and Goldsmith, Ben (Eds.) Australian Screen in the 2000s. Palgrave Macmillan, Switzerland, pp. 119-139.

- ^ "The Babadook Strikes Gold at Australian Academy Awards - Dread Central". dreadcentral.com. 29 January 2015.

- ^ Hawker, Philippa; Boyle, Finlay (7 January 2014). "AACTA international nominations 2015: The Babadook a surprise inclusion". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Hunt, Elle (11 June 2017). "The Babadook: how the horror movie monster became a gay icon". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Bradley, Laura (2017). "It's Official: The Gay Babadook Has Netflix Babashook". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Seavers, Kris (7 June 2017). "The Babadook is this year's Pride Month's unofficial mascot". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "The Babadook to raise bababucks at special LGBT charity screenings". News.

- ^ Topel, Fred (30 January 2019). "Director Jennifer Kent comments on those LGBT 'Babadook' memes [interview]". Bloody Disgusting.

- ^ Teeman, Tim (19 December 2014). "Grief: The Real Monster in The Babadook". The Daily Beast. The Daily Beast Company Ltd. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ a b c Khairy, Wael (22 November 2014). "Film Analysis: "The Babadook"". The Cinephile Fix. Wordpress. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Courtney, Enlow (17 October 2019). "THE BABADOOK, PARENTING, AND MENTAL ILLNESS". SYFY. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links[]

- The Babadook at IMDb

- The Babadook at AllMovie

- The Babadook at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Babadook trailer Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Fliks.com.au

- How Jennifer Kent made The Babadook at SBS Movies

- 2014 films

- English-language films

- 2014 horror films

- Australian supernatural horror films

- Demons in film

- 2014 directorial debut films

- Features based on short films

- Fictional demons and devils

- Films about grieving

- Films set in South Australia

- Films shot in Adelaide

- 2010s monster movies

- IFC Films films

- Films scored by Jed Kurzel

- Mother and son films