The Exorcist (film)

| The Exorcist | |

|---|---|

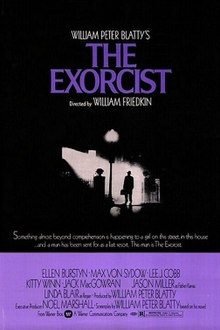

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | William Friedkin |

| Written by | William Peter Blatty |

| Based on | The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty |

| Produced by | William Peter Blatty |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Owen Roizman |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Jack Nitzsche |

Production company | Hoya Productions[1] |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros.[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 121 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million[2] |

| Box office | |

The Exorcist is a 1973 American supernatural horror film directed by William Friedkin and produced and written for the screen by William Peter Blatty, based on the 1971 novel of the same name by Blatty. The film stars Ellen Burstyn, Max von Sydow, Lee J. Cobb, Kitty Winn, Jack MacGowran (in his final film role), Jason Miller and Linda Blair. It is the first installment in The Exorcist film series, and follows the demonic possession of twelve year-old Regan and her mother's attempt to rescue her through an exorcism conducted by two Catholic priests.

Despite the book's bestseller status, Blatty, who produced, and Friedkin, his choice for director, had difficulty casting the film. After turning down, or being turned down by, major stars of the era, they cast Burstyn, a relative unknown, as well as unknowns Blair and Miller (author of a hit play with no film acting experience); the casting choices were vigorously opposed by studio executives at Warner Bros. Pictures. Principal photography was also difficult. A fire destroyed the majority of the set, and Blair and Burstyn suffered long-term injuries in on-set accidents. Ultimately production took twice as long as scheduled and cost more than twice the initial budget.

The Exorcist was released in 24 theaters in the United States and Canada in late December. Despite initial mixed critical reviews, audiences flocked to it, waiting in long lines during winter weather and many doing so more than once. Some viewers suffered adverse physical reactions, fainting or vomiting to scenes in which the protagonist undergoes a realistic cerebral angiography and later violently masturbates with a crucifix. Heart attacks and miscarriages were reported; a psychiatric journal published a paper on "cinematic neurosis" triggered by the film. Many children were allowed to see the film, leading to charges that the MPAA ratings board had accommodated Warner Brothers by giving the film an R-rating instead of the X-rating they thought it deserved, in order to ensure its commercial success. Several cities attempted to ban it outright or prevent children from attending.

The cultural conversation around the film, which also encompassed its treatment of Catholicism, helped it become the first horror film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture,[4][5] one of ten Academy Awards it was nominated for, winning for Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Sound. It was the highest-grossing R-rated horror film (unadjusted for inflation) until the 2017 release of It. The Exorcist has had a significant influence on popular culture[6][7] and has received critical acclaim, with several publications regarding it as one of the greatest horror films ever made.[5] English film critic Mark Kermode named it his "favorite film of all time".[8] In 2010, the Library of Congress selected the film to be preserved in its National Film Registry, citing it as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[9][10][11]

Plot[]

Theatrical cut[]

Lankester Merrin, a veteran Catholic priest is on an archaeological dig in the ancient city of Hatra in Iraq. Alerted by a colleague, he finds a sculpture that resembles Pazuzu, a demon of ancient origins with whose history Merrin is familiar. Soon afterwards, after consuming a small, white pill, Merrin encounters a statue towering over him in the image of Pazuzu, an omen warning him of a looming confrontation.

Meanwhile, in Georgetown, actress Chris MacNeil is living on location with her 12-year-old daughter Regan; she is starring in a film directed by her friend and associate Burke Dennings. During this time, small oddities begin to occur around the house, such as scratching from the attic without a source. After playing with a Ouija board and contacting a supposedly imaginary friend whom she calls Captain Howdy, Regan begins acting strangely, using obscene language, and exhibiting abnormal strength; additionally, there is poltergeist-like activity in the home at night. Chris hosts a party, during which Regan comes downstairs unannounced, tells one of the guests – an astronaut – that he will "die up there" and then urinates on the floor. Later that night, Regan's bed begins to shake and levitate violently. Chris consults a number of physicians, putting Regan through a battery of diagnostic tests, but the doctors find nothing physiologically wrong with her.

One night when Chris is out, Burke Dennings is babysitting a heavily sedated Regan. Chris returns to hear that Dennings has died, having fallen out of the window. Although this is assumed to have been an accident given Burke's history of heavy drinking, his death is investigated by Lieutenant William Kinderman. Kinderman interviews Chris. He also consults psychiatrist Father Damien Karras, a Jesuit priest struggling with his faith. Karras's crisis of faith is precipitated by the death of his mother, which he blames on himself.

The doctors, believing that Regan's aberrations are mostly psychological in origin, recommend an exorcism be performed. Chris arranges a meeting with Karras who, reluctant to engage spiritually, agrees to at least speak with Regan. As the two come face to face, Karras and Regan test each other's wits, although Karras is skeptical of the idea that anything supernatural is happening. Chris tearfully finds herself at a dead end and confides in Karras that Regan was the one who murdered Dennings, and begs him to find a solution. Over the next couple of days, Karras witnesses Regan speaking backward in different languages she does not know, and scars spelling out "HELP ME" appear on her stomach, convincing him she really is possessed by a demon. He implores the Church to let him perform an exorcism, but, feeling Karras is outmatched, the Church calls on Merrin to perform the exorcism while allowing Karras to assist.

The ritual begins as a battle of wills with Regan performing a series of horrific and vulgar acts. They attempt to exorcise the demon, but the spirit digs in, claiming to be the Devil himself. The spirit relentlessly toys with the priest and zeroes in on Karras, sensing his guilt from the passing of his mother. Karras weakens after the demon impersonates his late mother, and is excused by Merrin who continues the exorcism alone. Once he has gathered his strength, Karras re-enters the room and discovers Merrin dead of a heart attack. After he fails to revive Merrin, the enraged Karras grabs a laughing Regan and wrestles her to the ground. At Karras's invitation, the demon leaves Regan's body and takes hold of Karras. In a final moment of strength and self-sacrifice, Karras throws himself out the window before he can harm Regan, falling to his death down a set of stone steps and defeating the demon at last. Father Dyer, a friend of Karras, happens upon the scene and administers the last rites to Karras.

A few days later, Regan, now back to her normal self, prepares to leave for Los Angeles with her mother. Although Regan has no apparent recollection of her possession, she is moved by the sight of Dyer's clerical collar to kiss him on the cheek. As the car pulls away, Chris tells the driver to stop, and she gives Father Dyer a medallion that belonged to Karras. After they drive off, Dyer pauses at the top of the stone steps to give Regan's window one last look, and then turns to walk away.

Director's cut ending[]

In 2000, a version of the film known as the "Version You've Never Seen" or the "Extended Director's Cut" was released. In the ending of this version, when Chris gives Karras' medallion to Dyer, Dyer places it back in her hand and suggests that she keep it.[12] After she and Regan drive away, Dyer pauses at the top of the stone steps before walking away and coming across Kinderman, who narrowly missed Chris and Regan's departure; Kinderman and Dyer begin to develop a friendship.[12][13]

Cast[]

- Ellen Burstyn as Chris MacNeil

- Jason Miller as Father/Dr. Damien Karras, S.J.

- Linda Blair as Regan MacNeil

- Max von Sydow as Father Lankester Merrin

- Lee J. Cobb as Lieutenant William F. Kinderman

- Kitty Winn as Sharon Spencer

- Jack MacGowran as Burke Dennings

- Father William O'Malley as Father Joseph Dyer

- Father Thomas Bermingham as Tom, President of Georgetown University

- Peter Masterson as Dr. Barringer

- Robert Symonds as Dr. Taney

- Barton Heyman as Dr. Samuel Klein

- Rudolf Schündler as Karl, house servant

- Arthur Storch as the psychiatrist

- Vasiliki Maliaros as Karras' Mother

- Titos Vandis as Karras' Uncle

- Dick Callinan as Captain Billy Cutshaw

- William Peter Blatty as Producer Fromme

- Mercedes McCambridge as the voice of Pazuzu

- Eileen Dietz as the face of Pazuzu (uncredited)

Production[]

Writing[]

Aspects of Blatty's fictional novel were inspired by the 1949 exorcism performed on an anonymous young boy known as "Roland Doe" or "Robbie Mannheim" (pseudonyms) by the Jesuit priest Fr. William S. Bowdern, who formerly taught at both St. Louis University and St. Louis University High School. Doe's family became convinced the boy's aggressive behavior was attributable to demonic possession, and called upon the services of several Catholic priests, including Bowdern, to perform the rite of exorcism. It was one of three exorcisms to have been sanctioned by the Catholic Church in the United States at that time. Later analysis by paranormal skeptics has concluded that Doe was likely a mentally ill teenager acting out, as the actual events likely to have occurred (such as words being carved on skin) were such that they could have been faked by Doe himself.[5] The novel changed several details of the case, such as changing the sex of the allegedly possessed victim from a boy to a girl and changing the alleged victim's age.[4][5]

Although Friedkin has admitted he is very reluctant to speak about the factual aspects of the film, he made the film with the intention of immortalizing the events involving Doe that took place in 1949, and despite the relatively minor changes that were made, the film depicts everything that could be verified by those involved. In order to make the film, Friedkin was allowed access to the diaries of the priests involved, as well as the doctors and nurses; he also discussed the events with Doe's aunt in great detail. Friedkin has said that he does not believe that the "head-spinning" actually occurred, but this has been disputed. Friedkin is secular, coming from a Jewish family.[14]

Casting[]

The film's lead roles, particularly Regan, were not easily cast. Although many name stars of the era were considered for the role, with Stacy Keach actually having signed to play Father Karras at one point, Blatty and Friedkin ultimately went with less well-known actors, to the consternation of the studio.

Chris and Father Karras[]

The studio wanted Marlon Brando for the role of Lankester Merrin.[15] Friedkin immediately vetoed this by stating it would become a "Brando movie". Jack Nicholson was up for the part of Karras before Stacy Keach was hired by Blatty. According to Friedkin, Paul Newman also wanted to portray Karras.[16]

Friedkin then spotted Jason Miller following a performance of Miller's play That Championship Season in New York, and asked to talk to him. He originally went to talk to Miller solely about the lapsed Catholicism in the play as a background for the film. Since Miller had not read the novel, Friedkin left him a copy.[17]

Three A-list actresses of the time were considered for Chris. Friedkin first approached Audrey Hepburn, who said she was willing to take the role but only if the movie could be shot in Rome, since she had moved to Italy with her husband. Since that would have raised the costs of the movie considerably, as well as creating language barriers and making it impossible to work with crew members Friedkin was comfortable with, like cinematographer Owen Roizman, he looked next to Anne Bancroft. She, too, was willing but asked if production could be delayed nine months as she had just gotten pregnant. Again, Friedkin declined her request as he could not wait that long; he also did not think the material was something she would want to be working on while tending to a newborn, which might also make it more difficult for her to work. Jane Fonda, next on the list, turned down the film as a "piece of capitalist rip-off bullshit".[17][18]

Blatty also suggested his friend Shirley MacLaine for the part, but Friedkin was hesitant to cast her, given her lead role in another possession film, The Possession of Joel Delaney (1971) two years before.[17] Ellen Burstyn received the part after she phoned Friedkin and emphatically stated that she was "destined" to play Chris. Studio head Ted Ashley vigorously opposed casting her, not only telling Friedkin that he would do so over his dead body, but dramatizing that opposition by making Friedkin walk over him as he lay on the floor, then grabbing the director's leg and telling him he would come back from the dead if necessary to keep Friedkin from doing so. However, no other alternatives emerged, and Ashley relented.[17][19]

With Burstyn now set in the part, Friedkin was surprised when Miller called him back. He had read the novel, and told the director "that guy is me", referring to Father Karras. Miller had had a Catholic education, and had studied to be a Jesuit priest himself for three years at Catholic University of America until experiencing a crisis of faith, just as Karras at the beginning of the story. Friedkin thanked him for his interest but told him Keach had already been signed.[17]

Miller, who had done some stage acting but had never been in a film, asked to at least be given a screen test. After taking the train to Los Angeles since he disliked flying, Friedkin had the playwright and Burstyn do the scene where Chris tells Karras she thinks Regan might be possessed. Afterwards, he had Burstyn interview Miller about his life with the camera focusing on him from over her shoulder, and finally asked Miller to say Mass as if for the first time.[17]

Burstyn felt that Miller was too short for the part, unlike her boyfriend at the time, whom Friedkin had auditioned but passed on. The director felt the test was promising but, after viewing the footage the next morning, realized Miller's "dark good looks, haunted eyes, quiet intensity, and low, compassionate voice", qualities which to him evoked John Garfield, were exactly what the part needed. The studio bought out Keach's contract.[17]

Supporting roles[]

The film's supporting roles were more quickly cast. After Blatty showed Friedkin a photograph of Gerald Lankester Harding, his inspiration for Father Merrin, Friedkin immediately thought of Max von Sydow for the part; he accepted it as soon as he finished reading the script. While out seeing a play starring an actor who had been recommended to them for the film, Blatty and Friedkin ran into Lee J. Cobb, which led to his casting as Lt. Kinderman. Father William O'Malley, another Jesuit priest who taught English and theology at McQuaid Jesuit High School outside Rochester, New York, had become acquainted with Blatty through his criticism of the novel. After Blatty introduced him to Friedkin, they decided to cast him as Father Dyer, a character O'Malley had considered clichéd in the novel.[17]

Greek actor Titos Vandis was cast in the role of Father Karras's uncle. He wore a hat in one shot that obscured his face, as Friedkin felt that Vandis's face would be connected with his previous role in the Woody Allen film Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask).[20]

Regan[]

The question of whether or not such a young actress, even a talented one, could carry the film on her shoulders was an issue from the beginning. Film directors considered for the project were skeptical.[4] Mike Nichols had turned down the project specifically because he did not believe a 12-year-old girl capable of playing the part, as well as able to handle the likely psychological stress it would cause, could be found.[17]

The first actresses considered for the part were names known to the public. Pamelyn Ferdin, a veteran of science fiction and supernatural drama, was a candidate, but was ultimately turned down because her career thus far had made her too familiar to the public.[21] April Winchell was considered, until she developed pyelonephritis and could not work. Denise Nickerson, who had played Violet Beauregarde in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, was considered, but the material troubled her parents too much.[21] Anissa Jones, known for her role as Buffy in Family Affair, auditioned for the role, but she too was rejected, for much the same reason as Ferdin.

Friedkin had started to interview young women as old as 16 who looked young enough to play Regan, but was not finding any who he thought could.[17] Then Elinore Blair came in unannounced to the director's New York office with her daughter Linda; the agency representing Linda had not sent her for the part, but she had previously met with Warner Bros. Pictures' casting department and then with Friedkin.[22] Both mother and daughter impressed the director. Elinore was not a typical stage mother, and Linda's credits were primarily in modeling; she was mainly interested in showing and riding horses around her Westport, Connecticut, home. "[S]mart but not precocious. Cute but not beautiful. A normal, happy twelve-year-old girl", Friedkin later recalled.[17]

With Linda having demonstrated the personal qualities Friedkin was looking for, he then went on to see whether she could handle the material. He asked if she knew what The Exorcist was about; she told him she had read the book. "[I]t's about a little girl who gets possessed by the devil and does a whole bunch of bad things." Friedkin then asked her what sort of bad things she meant. "[S]he pushes a man out of her bedroom window and she hits her mother across the face and she masturbates with a crucifix."[17] Friedkin then asked Linda if she knew what masturbation meant. "It's like jerking off, isn't it?", and she giggled a little bit. "Have you ever done that?" he asked. "Sure; haven't you?" Linda responded. She was quickly cast as Regan after tests with Burstyn; Friedkin realized he needed to keep that level of spontaneity on set.[17]

Friedkin originally intended to use Blair's voice, electronically deepened and roughened, for the demon's dialogue. Although Friedkin felt this worked fine in some places, he felt scenes with the demon confronting the two priests lacked the dramatic power required and selected Oscar-winning actress Mercedes McCambridge, an experienced voice actress, to provide the demon's voice.[22] After filming, Warner Bros. did not include a credit for McCambridge, which led to Screen Actors Guild arbitration before she was credited for her performance.[23] Ken Nordine was also considered for the demon's voice, but Friedkin thought it would be best not to use a man's voice.[24]

Actress Eileen Dietz stood in for Blair in the crucifix scene, the fistfight with Father Karras, and other scenes that were too violent or disturbing for Blair to perform. She also appears as the face of Pazuzu.[25]

Direction[]

Warners had approached Arthur Penn, Stanley Kubrick, and Mike Nichols to direct, all of whom turned the project down.[26] Originally Mark Rydell was hired to direct, but William Peter Blatty insisted on Friedkin instead, because he wanted his film to have the same energy as Friedkin's previous film, The French Connection.[26] After a standoff with the studio, which initially refused to budge over Rydell, Blatty eventually got his way. Principal photography for The Exorcist began on August 21, 1972.[27] The shooting schedule was estimated to run 105 days, but ultimately ran well over 200.[27]

Friedkin went to extraordinary lengths manipulating the actors, reminiscent of the old Hollywood directing style, to get the genuine reactions he wanted. Yanked violently around in harnesses, both Blair and Burstyn suffered back injuries and their painful screams were included in the film.[22] Burstyn injured her back after landing on her coccyx when a stuntman jerked her around using a special effects cable during the scene when Regan slaps her mother.[22] According to the documentary Fear of God: The Making of the Exorcist, the injury did not cause permanent damage, although Burstyn was upset the shot of her screaming in pain was used in the film. After O'Malley confirmed to Friedkin that he trusted the director, Friedkin slapped him hard across the face to generate a deeply solemn reaction for the last rites scene; this offended the many Catholic crew members on the set. He also fired blanks[16] without warning on the set to elicit shock from Jason Miller for a take, and told Miller that the pea soup would hit him in the chest rather than the face in the projectile vomiting scene, resulting in his disgusted reaction. Lastly, he had Regan's bedroom set built inside a freezer so that the actors' breath could be visible on camera, which required the crew to wear cold weather gear.[22]

Filming[]

The film's opening sequences were filmed in and near the city of Mosul, Iraq. The archaeological dig site seen at the film's beginning is the actual site of ancient Hatra, south of Mosul.[28] Temperatures during the days filming took place there reached 54 °C (130 °F), limiting shooting to the early mornings and late evening.[29]

The stairs were padded with half-inch-thick (13 mm) rubber to film the death of the character Father Damien Karras. Because the house from which Karras falls was set back slightly from the steps, the film crew constructed an eastward extension with a false front to the house in order to film the scene.[30] The stuntman tumbled down the stairs twice. Georgetown University students charged people around $5 each to watch the stunt from the rooftops.[31][32]

Although the film is set in Washington, D.C., many interior scenes were shot in various parts of New York City. The MacNeil residence interiors were filmed at CECO Studios in Manhattan.[33] The bedroom set was refrigerated to capture the authentic icy breath of the actors in the exorcism scenes. It was chilled so much that a thin layer of snow fell onto the set one humid morning.[34] Since the set lighting warmed the air, it could only remain cold enough for three minutes of filming at a time.[35] Nevertheless, Blair, who was only in a thin nightgown while the crew wore cold weather clothing, said she cannot stand being cold.[34] Exteriors of the MacNeil house, were filmed at 36th and Prospect in Washington, the former site of E. D. E. N. Southworth's residence,[36] using a family home and a false east extension to convey that the home's windows were close to the steps.

The scenes involving Regan's medical tests were filmed at New York University Medical Center and were performed by actual medical staff that normally carried out the procedures.[29] Paul Bateson, convicted of murdering a journalist several years after the film, is the radiographer talking to Regan through the cerebral angiography.[37] In the film Regan first undergoes an electroencephalography (EEG), then the angiography, and finally a pneumoencephalography.

The scene in which Father Karras listens to the tapes of Regan's dialogue was filmed in the basement of Keating Hall at Fordham University in the Bronx.[38] William O'Malley, who plays Father Joseph Dyer in the film, is a real-life Jesuit and was assistant professor of theology at Fordham at the time.[39]

The interior of Karras' room at Georgetown was a meticulous reconstruction of Theology professor Father Thomas M. King, S.J.'s "corridor Jesuit" room in New North Hall. King's room was photographed by production staff after a visit by Blatty, a Georgetown graduate, and Friedkin. Upon returning to New York, every element of King's room, including posters and books, was recreated for the set, including a poster of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., a theologian on whom the character of Fr. Merrin was loosely based. Georgetown was paid $1,000 per day of filming, which included both exteriors such as Burstyn's first scene, shot on the steps of the Flemish Romanesque Healy Hall, and interiors such as the defilement of the statue of the Virgin Mary in Dahlgren Chapel, or the Archbishop's office, which is actually the office of the president of the university. One scene was filmed in The Tombs, a student hangout across from the steps that was founded by a Blatty classmate.[40]

Father Merrin's arrival scene[]

Father Merrin's arrival scene was filmed on Max von Sydow's first day of work. The scene where the elderly priest steps out of a cab and stands in front of the MacNeil residence, silhouetted in a misty streetlamp's glow and staring up at a beam of light from a bedroom window, is one of the most famous scenes in the movie. The shot was used for film posters and home DVD/VHS release covers. The scene and photo were inspired by the 1954 painting Empire of Light (L'Empire des lumières) by René Magritte.[41]

"Spider-walk" scene[]

Stuntwoman Ann Miles performed the spider-walk scene in November 1972. Friedkin deleted this scene against Blatty's objection just prior to the premiere, as he judged the scene as appearing too early in the film's plot. In the book, the spider-walk is more muted, consisting of Regan following Sharon around near the floor and flicking a snakelike tongue at her ankles. A take of this version of the scene was filmed but went unused. However, a different take showing Regan with blood flowing from her mouth was inserted into the 2000 Director's Cut of the film.

Editing[]

Special effects[]

The Exorcist contained a number of special effects, engineered by makeup artist Dick Smith. In one scene from the film, Max von Sydow is actually wearing more makeup than the possessed girl (Linda Blair). This was because director Friedkin wanted some very detailed facial close-ups. When this film was made, von Sydow was 44, though he was made up to look 74.[42] Alan McKenzie stated in his book Hollywood Tricks of the Trade that the fact "that audiences didn't realize von Sydow was wearing makeup at all is a tribute to the skills of veteran makeup artist Dick Smith."

Sound effects[]

Special sound effects for the film were created by Ron Nagle, Doc Siegel, Gonzalo Gavira, and Bob Fine.[43] Nagle spent two weeks recording animal sounds, including bees, dogs, hamsters, and pigs; these were incorporated into the multilayered mix of the demon's voice.[44] Gavira achieved the sound effect of Regan's head rotating by twisting a leather wallet.[44][45]

Alleged subliminal imagery[]

The Exorcist was also at the center of controversy due to its alleged use of subliminal imagery introduced as special effects during the production of the film. Wilson Bryan Key wrote a whole chapter on the film in his book Media Sexploitation alleging repeated use of subliminal and semi-subliminal imagery and sound effects. Key observed the use of the Pazuzu face (which Key mistakenly assumed was Jason Miller in death mask makeup, instead of actress Eileen Dietz) and claimed that the safety padding on the bedposts was shaped to cast phallic shadows on the wall and that a skull face is superimposed into one of Father Merrin's breath clouds. Key also wrote much about the sound design, identifying the use of pig squeals, for instance, and elaborating on his opinion of the subliminal intent of it all. A detailed article in the July/August 1991 issue of Video Watchdog examined the phenomenon, providing still frames identifying several uses of subliminal "flashing" throughout the film.[46]

In an interview from the same issue, Friedkin explained, "I saw subliminal cuts in a number of films before I ever put them in The Exorcist, and I thought it was a very effective storytelling device. ...The subliminal editing in The Exorcist was done for dramatic effect – to create, achieve, and sustain a kind of dreamlike state."[47] However, these quick, scary flashes have been labeled "[not] truly subliminal"[48] and "quasi-" or "semi-subliminal".[49] In an interview in a 1999 book about the film, The Exorcist author Blatty addressed the controversy by explaining that, "There are no subliminal images. If you can see it, it's not subliminal."[50]

Titles[]

The editing of the title sequence was the first major project for the film title designer Dan Perri. As a result of the success of The Exorcist, Perri went on to design opening titles for a number of major films including Taxi Driver (1976), Star Wars (1977), and Gangs of New York (2002).[51]

Music[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2019) |

Lalo Schifrin's working score was rejected by Friedkin. Schifrin had written six minutes of music for the initial film trailer but audiences were reportedly too scared by its combination of sights and sounds. According to Schifrin, Warner Bros. executives told Friedkin to instruct him to tone it down with softer music, but Friedkin did not relay the message.[52] It has been claimed Schifrin later used the music written for The Exorcist for The Amityville Horror,[53] but he has denied this in interviews. According to The Fear of God: The Making of the Exorcist on the 25th Anniversary DVD release of the film, Friedkin took the tapes that Schifrin had recorded and threw them away in the studio parking lot.[54]

In the soundtrack liner notes for his 1977 film, Sorcerer, Friedkin said that if he had heard the music of Tangerine Dream earlier, then he would have had them score The Exorcist. Instead, he used modern classical compositions, including portions of the 1972 Cello Concerto No. 1, of Polymorphia, and other pieces by Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki, Five Pieces for Orchestra by Austrian composer Anton Webern as well as some original music by Jack Nitzsche. The music was heard only during scene transitions. The 2000 "Version You've Never Seen" features new original music by Steve Boeddeker, as well as brief source music by Les Baxter.

What is now considered the "Theme from The Exorcist", i.e. the piano-based melody which opens the first part of Tubular Bells,[55] the 1973 debut album by English progressive rock musician Mike Oldfield, became very popular after the film's release, although Oldfield himself was not impressed with the way his work was used.[56]

In 1998 a restored and remastered soundtrack was released by Warner Bros. (without Tubular Bells) that included three pieces from Lalo Schifrin's rejected score. The pieces are "Music from the unused Trailer", an 11-minute "Suite from the Unused Score", and "Rock Ballad (Unused Theme)".

That same year, the Japanese version of the original soundtrack LP did not include the Schifrin pieces but did include the main theme from Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield, and the movement titled Night of the Electric Insects from George Crumb's string quartet Black Angels.[57]

Waxwork Records released the score in 2017 on two different variations of 180 gram vinyl, "Pazuzu" with clear and black smoke and "Exorcism" that featured blue and black smoke. The record was re-mastered from the original tapes; it included liner notes from Friedkin with art by Justin Erickson from Phantom City Creative.[58]

The Greek song playing on the radio when Father Karras leaves his mother's house is called "Paramythaki mou" (My Tale) and is sung by Giannis Kalatzis. Lyric writer Lefteris Papadopoulos has admitted that a few years later when he was in financial difficulties he asked for some compensation for the intellectual rights of the song. Part of Hans Werner Henze's 1966 composition Fantasia for Strings is played over the closing credits.[59][60]

Release[]

Theatrical run[]

Upon its December 26, 1973, release, the film received mixed reviews from critics, "ranging from 'classic' to 'claptrap'".[61] Audience reaction was strong, however, with many viewers waiting in long lines in cold temperatures to see it again and again.[62] It opened in 24 theaters grossing $1.9 million in its first week, setting house records in each theater[63] and within its first month the film had grossed $7.4 million nationwide, by which time Warners' executives expected the film to easily surpass My Fair Lady's $34 million take to become the studio's most financially successful film.[64]

Home media[]

Special edition 25th anniversary VHS and DVD release[]

A limited special edition box set was released in 1998 for the film's 25th anniversary; it was limited to 50,000 copies, with available copies circulating around the Internet. There are two versions: a special edition VHS released on November 10, 1998,[65] and a special edition DVD released on December 1, 1998.[66] The only difference between the two copies is the recording format. A 25th anniversary edition was released on DVD by Warner Home Video on August 5, 2003.

DVD features[]

- The original film with restored film and digitally remastered audio, with a 1.85:1 widescreen aspect ratio.

- An introduction by director Friedkin.

- The 1998 BBC documentary The Fear of God: The Making of "The Exorcist".

- Two audio commentaries.

- Interviews with the director and writer.

- Theatrical trailers and TV spots.

Box features[]

- A commemorative 52-page tribute book, covering highlights of the film's preparation, production, and release; features previously unreleased historical data and archival photographs.

- Limited edition soundtrack CD of the film's score, including the original (unused) soundtrack ("Tubular Bells" and "Night of the Electric Insects" omitted).

- Eight lobby card reprints.

- Exclusive senitype film frame (magnification included).

Extended edition DVD releases[]

The extended edition labeled "The Version You've Never Seen" (which was released theatrically in 2000) was released on DVD on February 3, 2004.[67]

The extended edition was later re-released on DVD (and released on Blu-ray) with slight alterations under the new label "Extended Director's Cut" on October 5, 2010.[68]

Blu-ray[]

In an interview with DVD Review, Friedkin mentioned that he was scheduled to begin work on The Exorcist Blu-ray on December 2, 2008.[69] This edition features a new restoration, including both the 1973 theatrical version and the 2000 "Version You've Never Seen" (re-labeled as "Extended Director's Cut").[70] It was released on October 5, 2010.[71][72][73] A 40th Anniversary Edition Blu-ray was released on October 8, 2013, containing both cuts of the film and many of the previously released bonus features in addition to two featurettes that revolve around author William Peter Blatty.[74]

The Exorcist: The Complete Anthology[]

The Exorcist: The Complete Anthology (box set) was released on DVD on October 10, 2006,[75] and on Blu-ray on September 23, 2014.[76] This collection includes the original theatrical release version of The Exorcist, the extended version (labelled The Exorcist: The Version You've Never Seen on the DVD release and The Exorcist: Extended Director's Cut on the Blu-ray release), the sequels Exorcist II: The Heretic and The Exorcist III, and the prequels Exorcist: The Beginning and Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist.

Reception[]

Box office[]

Since it was a horror film that had gone well over budget and did not have any major stars in the lead roles, Warner did not have high expectations for The Exorcist. It did not preview the film for critics and booked its initial release for only 30 screens in 24 theaters,[63] mostly in large cities.[77] It grossed $1.9 million in its first week, setting house records in each theater.[63] The huge crowds attracted to the film forced the studio to expand it into wide release very quickly; at the time that releasing strategy was rarely used for anything but exploitation films (two years later, Universal would learn from The Exorcist and open Jaws on 500 screens across the country).[78]

None of the theaters were in Black neighborhoods such as South Central Los Angeles since the studio did not expect black people to take much interest in the film; after the theater in predominantly white Westwood had shown the film was overwhelmed with moviegoers from South Central it was quickly booked into theaters in that neighborhood.[77] Black American enthusiasm for The Exorcist has been credited with ending mainstream studio support for blaxploitation movies, since Hollywood realized that black audiences would flock to films that did not have content specifically geared to them.[79]

The film earned $66.3 million in distributors' rentals during its theatrical release in 1974 in the United States and Canada, becoming the second most popular film of that year (trailing The Sting which earned $68.5 million)[80] and Warners' highest-grossing film of all time.[81] The film earned rentals of $46 million overseas[82] for a worldwide total of $112.3 million.

After several reissues, the film has grossed $232.6 million in the United States and Canada,[83] which when adjusted for inflation, makes it the ninth highest-grossing film of all time in the U.S. and Canada and the top-grossing R-rated film of all time.[84] As of 2019, it has grossed $441 million worldwide.[83] Adjusted to 2014 prices, The Exorcist has grossed $1.8 billion.[85]

Critical response[]

Stanley Kauffmann, in The New Republic, wrote, "This is the scariest film I've seen in years – the only scary film I've seen in years. ...If you want to be shaken – and I found out, while the picture was going, that that's what I wanted – then The Exorcist will scare the hell out of you".[86][87] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety noted that it was "an expert telling of a supernatural horror story. ...The climactic sequences assault the senses and the intellect with pure cinematic terror".[88] In the magazine publication Castle of Frankenstein, Joe Dante called it "an amazing film, and one destined to become at the very least a horror classic. Director Friedkin's film will be profoundly disturbing to all audiences, especially the more sensitive and those who tend to 'live' the movies they see. ...Suffice it to say, there has never been anything like this on the screen before".[89] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film a complete 4 star review, praising the actors (particularly Burstyn) and the convincing special effects, but at the end of the review wrote, "I am not sure exactly what reasons people will have for seeing this movie; surely enjoyment won't be one, because what we get here aren't the delicious chills of a Vincent Price thriller, but raw and painful experience. Are people so numb they need movies of this intensity in order to feel anything at all?"[90] Ebert, while praising the film, believed the special effects to be unusually graphic. He wrote, "That it received an R rating and not the X is stupefying".[90]

Vincent Canby, writing in The New York Times, dismissed The Exorcist as "a chunk of elegant occultist claptrap ... a practically impossible film to sit through. ...It establishes a new low for grotesque special effects."[91] Andrew Sarris of The Village Voice complained that "Friedkin's biggest weakness is his inability to provide enough visual information about his characters. ...Whole passages of the movie's exposition were one long buzz of small talk and name droppings. ...The Exorcist succeeds on one level as an effectively excruciating entertainment, but on another, deeper level it is a thoroughly evil film".[92] Writing in Rolling Stone, Jon Landau felt the film was "nothing more than a religious porn film, the gaudiest piece of shlock this side of Cecil B. DeMille (minus that gentleman's wit and ability to tell a story)."[93]

Angiography scene[]

The angiography scene, in which a needle is inserted into Regan's neck and spurts blood and which closely imitates the real-life procedure,[94] has come under some criticism. In his 1986 Guide for the Film Fanatic, Danny Peary called it the film's "most needless scene".[95] British comedian Graeme Garden, trained as a physician, agreed the scene was "genuinely disturbing" in his review for the New Scientist; he called it "the really irresponsible feature of this film".[96]

Medical professionals have described the scene as a realistic depiction of the procedure. It is also of historical interest in the field, as around the time of the film's release, radiologists had begun to stop using the carotid artery for the puncture as they do in the film, in favor of a more distant artery.[97][98] It has also been described as the most realistic depiction of a medical procedure in a popular film.[37] Friedkin said in his 2012 commentary on the DVD release of the 2000 cut that the scene was used as a training film for radiologists for years afterwards.[94]

Rating controversy[]

The Motion Picture Association of America's (MPAA) ratings board had been established several years before to replace the Motion Picture Production Code after it expired in 1968. It had already been criticized for its indirect censorship: as many as a third of the films submitted to it had had to be recut after being rated X, meaning no minors could be admitted. Since many theaters would not show such films, and newspapers would not run ads for them, the X rating greatly limited a non-pornographic film's commercial prospects.[77]

While Friedkin wanted more blood and gore in The Exorcist than had been in any Hollywood film previously, he also needed the film to have an R rating (children admitted only with an adult) to reach a large audience. Before release, Aaron Stern, the head of the MPAA ratings board, decided to watch the film himself before the rest of the board. He then called Friedkin and said that since The Exorcist was "an important film", he would allow it to receive an R rating without any cuts.[77]

Some critics, both anticipating and reacting to reports of the film's effect on children who might be or had been taken to see it, questioned the R rating. While he had praised the film, Roy Meacham, a critic for Metromedia television stations based in Washington, D.C., wrote in The New York Times in February 1974 that he had strongly cautioned that children should not be allowed to see it at all, a warning his station repeated for several days. Nevertheless, some had, and he had heard of one girl being taken from the theater in an ambulance.[99]

In Washington, the film drew strong interest as well since it was a rare film set in the area that did not involve government activity.[100] Children Meacham saw leaving showings, he recalled, "were drained and drawn afterward; their eyes had a look I had never seen before". He suggested that the ratings board had somehow yielded to pressure from Warners not to give the film an X rating, which would have likely limited its economic prospects, and was skeptical of MPAA head Jack Valenti's claims that since the film had no sex or nudity, it could receive an R. After a week in Washington's theaters, Meacham recalled, authorities cited the crucifix scene to invoke a local ordinance that forbid minors from seeing any scenes with sexual content even where the actors were fully clothed; police warned theaters that staff would be arrested if any minors were admitted to The Exorcist.[99]

"The review board [has] surrendered all right to the claim that it provides moral and ethical leadership to the movie industry", Meacham wrote. He feared that, as a result, communities across the country would feel it necessary to pass their own, perhaps more restrictive, laws regarding the content of movies that could be shown in their jurisdictions: "For if the movie industry cannot provide safeguards for minors, authorities will have to".[99]

Two communities, Boston and Hattiesburg, Mississippi, attempted to prevent the film from being shown outright in their jurisdictions. A court in the former city blocked the ban, saying the film did not meet the U.S. Supreme Court's standard of obscenity.[101] Nonetheless, in Boston the authorities told theaters they could not admit any minors despite the R rating.[77] In Mississippi, the theater chain showing the movie was convicted at trial, but the state's Supreme Court overturned the conviction in 1976, finding that the state's obscenity statute was too vague to be enforceable in the wake of the Supreme Court's 1972 Miller v. California decision which laid down a new standard for obscenity.[102]

New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael echoed Meacham's insinuations that the board had yielded to studio pressure in rating the film R: "If The Exorcist had cost under a million or been made abroad, it would almost certainly be an X film. But when a movie is as expensive as this one, the [board] doesn't dare give it an X".[77]

There was also concern that theaters were not strictly enforcing, or even enforcing at all, the R rating, allowing unaccompanied minors to view the film. Times critic Lawrence Van Gelder reported that a 16-year-old girl in California said that not only was she sold a ticket to see the film despite no adult being with her, others who seemed even younger were able to do so as well.[64] On the other hand, another Times writer, Judy Lee Klemesrud, said she saw no unaccompanied minors, and indeed very few minors, when she went to see the film in Manhattan. Nevertheless, "I think that if a movie ever deserved an X rating simply because it would keep the kids out of the theater, it is The Exorcist".[62]

In 1974, Stern's tenure as chairman of the MPAA ratings board ended. His eventual replacement, Richard Heffner, asked during the interview process about films with controversial ratings, including The Exorcist, said: "How could anything be worse than this? And it got an R?" After he took over as head, he would spearhead efforts to be more aggressive with the X rating, especially over violence in films.[77]

Viewing restrictions in UK[]

The Exorcist was released in London on March 14, 1974.[103] The film was protested against around the UK by the Nationwide Festival of Light, a Christian public action group concerned with the influence of media on society, and especially on the young. These protests involved members of local clergy and concerned citizens handing out leaflets to those queuing to see the film, offering spiritual support afterwards for those who asked for it.[104] A letter-writing campaign to local councils by the Nationwide Festival of Light led many councils to screen The Exorcist before permitting it to be screened in their council district.[105] This led to the film's being banned from exhibition in a number of counties, such as in Dinefwr and Ceredigion in Wales.[106][107]

The Exorcist was available on home video from 1981 in the UK.[108] After the passage of the Video Recordings Act 1984, the film was submitted to the British Board of Film Classification for a home video certificate. James Ferman, Director of the Board, vetoed the decision to grant a certificate to the film, despite the majority of the group willing to pass it. It was out of Ferman's concerns that, even with a proposed 18 certificate, the film's notoriety would entice underage viewers to seek it out. As a result, all video copies of The Exorcist were withdrawn in the UK in 1988 and remained unavailable for purchase until 1999.[108]

Following a successful re-release in cinemas in 1998, the film was submitted for home video release again in February 1999,[109] and was passed uncut with an 18 certificate, signifying a relaxation of the censorship rules with relation to home video in the UK, in part due to James Ferman's departure. The film was shown on terrestrial television in the UK for the first time in 2001, on Channel 4.[110]

Since release[]

The Exorcist set box office records that stood for many years. For almost half a century, until the 2017 adaptation of Stephen King's It, it was the top-grossing R-rated horror film.[111] In 1999, The Sixth Sense finally bested The Exorcist as the highest-grossing supernatural horror film; it remains in third place after It claimed that title as well.[112] On both charts The Exorcist, along with The Blair Witch Project, are the only 20th-century releases in the top 10.[111][112]

Since its release, The Exorcist's critical reputation has grown considerably. According to the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 83 percent of critics have given the film a positive review based on 83 reviews, with an average rating of 8.30/10. The site's critics consensus states: "The Exorcist rides its supernatural theme to magical effect, with remarkable special effects and an eerie atmosphere, resulting in one of the scariest films of all time".[113] At Metacritic, which assigns and normalizes scores of critic reviews, the film has a weighted average score of 82 out of 100 based on 20 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[114] Chicago Tribune film critic Gene Siskel placed it in the top five films released that year.[115] BBC film critic Mark Kermode believes the film to be the best film ever made, saying: "There's a theory that great films give back to you whatever it is you bring to them. It's absolutely true with The Exorcist – it reflects the anxieties of the audience. Some people think it's an outright horror-fest, but I don't. It was written by a devout Catholic who hoped it would make people think positively about the existence of God. William Peter Blatty, who wrote the book, thought that if there are demons then there are also angels and life after death. He couldn't see why people thought it was scary. I've seen it about 200 times and every time I see something I haven't seen before".[116]

Director Martin Scorsese placed The Exorcist on his list of the 11 scariest horror films of all time.[117] Directors Stanley Kubrick, Robert Eggers, Alex Proyas and David Fincher placed The Exorcist as one of their favorite films.[118][119][120][121] The musician Elton John listed the Exorcist in his five favorite films of all time.[122] In 2008, the film was selected by Empire as one of The 500 Greatest Movies Ever Made.[123] It was also placed on a similar list of 1000 films by The New York Times.[124]

Audience reaction[]

On December 26 a movie called The Exorcist opened in theatres across the country and since then all Hell has broken loose.

Despite its mixed reviews and the controversies over its content and viewer reaction, The Exorcist was a runaway hit. In New York City, where its initial run was limited to a few theaters, patrons endured cold as severe as 6 °F (−14 °C) sometimes with rain and sleet,[64] waiting for hours in long lines during what is normally a slow time of year for the movies to buy tickets, many not for the first time. The crowds gathered outside theaters, sometimes rioted, and police were called in to quell disturbances in not only New York but Kansas City.[77]

The New York Times asked some of those in line what drew them there. Those who had read the novel accounted for about a third; they wanted to see if the film could realistically depict some of the scenes in the book. Others said: "We're here because we're nuts and because we wanted to be part of the madness". A repeat viewer told the newspaper that it was the best horror film he had seen in decades, "much better than Psycho. You feel contaminated when you leave the theater. There's something that is impossible to erase". Many made a point of saying that they had either never waited in line that long for a movie before, or not in a long time. "It makes the movie better," William Hurt, then a drama student at Juilliard, said of the experience. "The more you pay for something, the more it's worth."[62]

Reports of strong audience reactions were widespread, many including accounts of nausea and fainting. A woman in New York was said to have miscarried during a showing.[62] Some theaters have been said to have provided "Exorcist barf bags";[125] while there are no contemporary reports of even providing regular sickness bags, Mad magazine depicted one on the cover of its October 1974 issue, which contained a parody of the film.[100] A reviewer for Cinefantastique said that there was so much vomit in the bathroom at the showing he attended that it was impossible to reach the sinks.[78]

Other theaters arranged for ambulances to be on call. Some patrons had to be helped to leave the places they had hidden in theaters. Despite its lack of any supernatural content, many audience members found the angiography, where blood spurts from the tube inserted into Regan's neck, to be the film's most unsettling scene (Blatty said he only watched it once, while the film was being edited, and avoided it on every other viewing).[126] Friedkin speculates that it is easier to empathize with Regan in that scene, as compared to what she suffers while possessed later in the film.[95][96][127][128]

In 1975, The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease published a paper by a psychiatrist documenting four cases of what he called "cinematic neurosis" triggered by viewing the film. In all he believed the neurosis was already present and merely triggered by viewing scenes in the film, particularly those depicting Regan's possession. He recommended that treating physicians view the movie with their patient to help him or her identify the sources of their trauma.[129]

"The Exorcist ... was one of the rare horror movies that became part of the national conversation", wrote Jason Zinoman almost 40 years later: "It was a movie you needed to have an opinion about". Three separate production histories were published. Journalists complained that coverage of the film and its controversies was distracting the public from the ongoing Watergate scandal.[77]

Much of the coverage, in fact, focused on the audience which, in the later words of film historian William Paul, "had become a spectacle equal to the film". He cites an Associated Press cartoon in which a couple trying to purchase tickets to the film was told that while the film itself is sold out, "we're selling tickets to the lobby to watch the audience." Paul does not think any other film's audience has received as much coverage as The Exorcist's.[78]

Legal disputes[]

Within a year of The Exorcist's release, two films were quickly made that appeared to appropriate elements of its plot or production design. Warner took legal action against the producers of both, accusing them of copyright infringement. The lawsuits resulted in one film being pulled from distribution and the other one having to change its advertisements.[130]

Abby, released almost a year after The Exorcist, put a blaxploitation spin on the material. In it a Yoruba demon released during an archeological dig in Africa crosses the Atlantic Ocean and possesses the archaeologist's daughter at home in Kentucky. Director William Girdler acknowledged the movie was intended to cash in on the success of The Exorcist. Warner's lawsuit early in 1975 resulted in most prints of the film being confiscated; the film has rarely been screened since and is not available on any home media.[131]

Later, in 1975, Warner Bros. brought suit against Film Ventures International (FVI) over Beyond the Door, which had also been released near the end of 1974, alleging that its main character, also a possessed woman whose head spins around completely, projectile vomits and speaks with a deep voice when possessed, infringed the studio's copyright on Regan. Judge David W. Williams of the United States District Court for the Central District of California held first that since Blatty had based the character on what he was told was a true story, Regan was not original to either film and thus Warner could not hold a copyright on Regan. Even if she had been a creation, she could not be copyrighted since she was subordinate to the story. The writers of the FVI film had also further distanced themselves from an infringement claim by having their possessed female, Jessica, be a pregnant adult woman.[130]

However, he found that some of Beyond the Door's advertising graphics, such as an image of light coming from behind a door into a darkened room, and the letter "T" drawn as a Christian cross, were similar enough to those used to promote The Exorcist that the public could reasonably have been confused into thinking the two films were the same, or made by the same people, and enjoined FVI from further use of those graphics.[130]

Legacy[]

"The Exorcist has done for the horror film what 2001 did for science fiction", wrote the Cinefantastique reviewer who had described the vomit-covered bathroom, "legitimizing it in the eyes of thousands who previously considered horror movies nothing more than a giggle".[78] In the years following, studios allotted large budgets to films like The Omen, The Sentinel, Burnt Offerings, Audrey Rose and The Amityville Horror, all of which had similar themes or plot elements and cast established stars,[132] who until then often avoided the genre until their later years.[77]

The film's success led Warner to initiate a sequel, one of the first times a studio had done that with a major film, launching a franchise. While many of the classic horror films of the 1930s, like Frankenstein and King Kong had spawned series of films over the decades, the practice had declined in the 60s, and although there had been some exceptions, like Bride of Frankenstein, most sequels had been considered secondary properties for the studios. The other big-budget horror films made in the wake of The Exorcist also led to sequels and franchises of their own.[77]

Accolades[]

The Exorcist was nominated for ten Academy Awards in 1974, winning two. It was the first horror film to be nominated for Best Picture.[133]

| Award | Category | Nominees | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[133] | Best Picture | William Peter Blatty | Nominated |

| Best Director | William Friedkin | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Ellen Burstyn | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Jason Miller | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Linda Blair | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay – Based on Material from Another Medium | William Peter Blatty | Won | |

| Best Art Direction | Bill Malley and Jerry Wunderlich | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Owen Roizman | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Jordan Leondopoulos, Bud Smith, Evan Lottman and Norman Gay | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Robert Knudson and Chris Newman | Won | |

| Golden Globe Awards[134] | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Won | |

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Ellen Burstyn | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Max von Sydow | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture | Linda Blair | Won | |

| Best Director – Motion Picture | William Friedkin | Won | |

| Best Screenplay – Motion Picture | William Peter Blatty | Won | |

| Most Promising Newcomer – Female | Linda Blair | Nominated | |

American Film Institute Lists[]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – #3

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Regan MacNeil – #9 Villain

Alternative and uncut versions[]

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2018) |

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (March 2019) |

Several versions of The Exorcist have been released:

- The 1979 theatrical reissue was converted to 70mm, with its 1.75:1 ratio[135] expanded to 2.20:1 to use all the available screen width that 70mm offers. This was also the first time the sound was remixed to six-channel Dolby Stereo. Almost all video versions feature this soundtrack.

- The network TV version originally broadcast on CBS in 1980 was edited by Friedkin, who filmed an insert of the Virgin Mary statue crying blood to replace the desecrated statue image. Friedkin himself delivered the demon's new, censored dialogue because he was unwilling to work with Mercedes McCambridge again. The lines "Your mother sucks cocks in hell, Karras, you faithless slime!" and "Shove it up your ass, you faggot" were redubbed as "Your mother still rots in hell" and "Shut your face, you faggot". Several of Chris' lines were redubbed by Burstyn, replacing "Jesus Christ" with "Judas Priest" and omitting the expletive "fuck". Moments in which Regan masturbates with a crucifix and forces her mother's head into her crotch are removed, along with most of the character's profanity. There is also a brief alternative shot shortly after Merrin arrives at the MacNeil house of Regan's face morphing into the demon's white visage (theatrical versions show only the beginning of the transformation).

- In some network versions Regan is not masturbating but having another fit.

- The 25th Anniversary Special Edition DVD includes the original ending (not used in the theatrical release) as a special feature: as Father Dyer walks away from the MacNeil residence, he is approached by Lt. Kinderman. They talk briefly about Regan and the events that took place and then Kinderman invites Dyer to the movies to see Wuthering Heights. Kinderman quotes Casablanca, telling Dyer, "I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship".

- The Special Edition DVD contains a 75-minute documentary on the making of The Exorcist titled The Fear of God, which features screen tests and additional deleted scenes.

- The scene in which the demonic entity leaves Father Karras was originally achieved by filming Miller in possession makeup, then stopping the camera and shooting him again with makeup removed. This creates a noticeable jump in Father Karras' position as he is unpossessed. The 25th anniversary video smooths over the jumpy transition with a subtle computer morphing effect. This update was not featured in prints used for Warner Bros. 75th anniversary film festivals.

- A new edition labeled "The Version You've Never Seen" (later re-labeled "Extended Director's Cut") was released in theaters on September 22, 2000, and included new additions and changes.

- In both the TV-PG and TV-14 rated network edits, the image of the obscenely defiled statue of the Virgin Mary is intact, appearing on-screen for several more seconds in the TV-14 version. In the original TV airings, the desecrated statue was replaced by an alternative version showing the face smashed in, but no other defilement. Edits may vary between networks; non-premium cable networks usually show only edited/censored versions of the film.

- The 25th Anniversary DVD retains the original theatrical ending and includes the extended ending with Dyer and Kinderman as a special feature (as opposed to the "Version You've Never Seen" ending, which features Dyer and Kinderman but omits the Casablanca reference).

- The Exorcist: The Complete Anthology (box set) was released on DVD in October, 2006, and on Blu-ray in September, 2014. This collection includes the original theatrical release of The Exorcist; the extended version, The Exorcist: The Version You've Never Seen; Exorcist II: The Heretic; The Exorcist III; and two prequels: Exorcist: The Beginning, and Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist. Morgan Creek, the current owner of the franchise, produced a television series of Blatty's novel, which is also the basis for the original film.[citation needed]

In 1998, Warner Bros. re-released the digitally remastered DVD of The Exorcist: 25th Anniversary Special Edition. The DVD includes the BBC documentary, The Fear of God: The Making of The Exorcist,[136] highlighting a never-before-seen original non-bloody variant of the spider-walk scene.

To appease the screenwriter and some fans of The Exorcist, Friedkin reinstated the bloody variant of the spider-walk scene for the 2000 theatrical re-release of The Exorcist: The Version You've Never Seen. In October 2010, Warner Bros. released The Exorcist (Extended Director's Cut & Original Theatrical Edition) on Blu-ray, which includes behind-the-scenes footage of the spider-walk scene. Linda R. Hager, the lighting double for Linda Blair, was incorrectly credited as the stunt performer. In 2015, Warner Bros. finally acknowledged that stuntwoman Ann Miles is the only person who performed the stunt.

Sequels[]

The film has gone on to spawn multiple sequels and an overarching media franchise including a television series.

Direct sequel[]

In August 2020, it was announced that a reboot of the film from Morgan Creek Entertainment is slated for release in 2021.[137][138] The announcement received a generally negative reaction from audiences loyal to the original and resulted in a petition being launched to have the project canceled.[139][140] In December 2020, Blumhouse and Morgan Creek announced that the reboot would be a "direct sequel" to the 1973 film and that David Gordon Green would direct.[141][142][143]

Related works[]

Blatty's script for the film has been published on several occasions. In 1974 he published the book William Peter Blatty on The Exorcist: From Novel to Film, which included the first draft of the screenplay.[144] In 1998 the script was published in an anthology titled The Exorcist/Legion - Two Classic Screenplays,[145] and again as a standalone text in 2000.[146]

See also[]

- 1973 in film

- List of American films of 1973

- List of film and television accidents

- List of highest-grossing films in the United States and Canada

- List of horror films of 1973

- List of films considered the best

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Exorcist (1973)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on February 17, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Exorcist – Box Office Data, DVD and Blu-ray Sales, Movie News, Cast and Crew Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Exorcist (1973)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Susman, Gary (December 26, 2013). "'The Exorcist': 25 Things You Didn't Know About the Terrifying Horror Classic". Moviefone.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The Cold Hard Facts Behind the Story that Inspired "The Exorcist"". Strange Magazine. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Layton, Julia (September 8, 2005). "How Exorcism Works". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ "Allmovie.com". Allmovie.com. September 9, 2005. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ Nunziata, Nick (October 31, 2015). "5 films that frightened the life out of Mark Kermode: 'The Exorcist has never failed me'". digitalspy.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Mike (December 28, 2010). "'Empire Strikes Back,' 'Airplane!' Among 25 Movies Named to National Film Registry". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ^ "Hollywood Blockbusters, Independent Films and Shorts Selected for 2010 National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Collins, Brian (May 8, 2012). "Collins' Crypt: The Exorcist Director's Cut Vs. Theatrical Versions". Birth.Movies.Death. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Kermode 2008, p. 83.

- ^ [1] Archived August 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine The Diane Rehm Show

- ^ Coffin, Patrick (December 1, 2013). "The Unbearable Frightness of Being". Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b DallasFilmSociety (April 19, 2013). "William Friedkin, director of THE EXORCIST at the 2013 Dallas International Film Festival". Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Adams, Ryan (April 29, 2013). "William Friedkin on casting The Exorcist". Awards Daily. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Seth Abramovitch and Chip Pope (October 1, 2018). "William Friedkin: The Exorcist". It Happened in Hollywood (Podcast). The Hollywood Reporter. Event occurs at 7:30–9:20. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ Emery, Robert J. (2000). The directors: in their own words. 2. TV Books. p. 258. ISBN 1575001292.

- ^ Clagett, Thomas (1990). William Friedkin: Films of Aberration, Obsession, and Reality. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 113–114. ISBN 0-89950-262-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nastasi, Alison (February 21, 2015). "The Actors Who Turned Down Controversial Movie Roles". Flavorwire. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Friedkin, William (director) (1998). The Fear of God: 25 Years of 'The Exorcist'. BBC (Documentary). Warner Bros.

- ^ "The Exorcist actress Mercedes McCambridge dies at 85". USA Today. March 17, 2004. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ DallasFilmSociety (April 19, 2013). "William Friedkin, director of THE EXORCIST at the 2013 Dallas International Film Festival". Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ ""We argued over the crucifix scene": what it was like being the demon in The Exorcist". New Statesman. February 5, 2020. Archived from the original on November 2, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kermode 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Biskind 1999, p. 216.

- ^ Friedkin, William (Director) (2000). The Exorcist: The Version You've Never Seen; director's commentary (audio track) (Motion picture). Iraq, Washington, D.C.: Warner Bros.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McLaughlin, Katie (October 31, 2013). "'The Exorcist' still turns heads at 40". CNN. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Truitt, Brian (October 7, 2013). "'Exorcist' creators haunt Georgetown thirty years later". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2014.

- ^ "Excorcist Steps in Washington, DC". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 5, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ The Fear of God: The Making of The Exorcist https://m.imdb.com/title/tt0237235/

- ^ Kermode 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Friedkin's – The Exorcist". Thefleshfarm.com. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ Slovick, Matt (1996). "The Exorcist". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ "Why Do the Exorcist Steps Exist in the First Place?". The Georgetown Metropolitan. October 30, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

There’s an interesting article in the Washington Post from December 1894 profiling the elderly famous author Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth who lived in a cottage perched next door on Prospect. Here it is after she passed away when it became a bit of a tourist trap:...The cottage was demolished in 1942. In 1950 a new townhouse was constructed in its place. That is the Exorcist house

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miller, Matt (October 25, 2018). "Searching For the Truth About the Actual Murderer in The Exorcist". Esquire. Archived from the original on December 28, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Hayes, Cathy (July 2, 2012). ""Exorcist" priest gets the ax from Fordham school for his old school ways". Irish Central. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ Larnick, Eric (October 6, 2010). "20 Things You Didn't Know About 'The Exorcist'". Moviefone. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Zak, Dan (October 30, 2013). "William Peter Blatty, writer of 'The Exorcist,' slips back into the light for its 40th anniversary". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Faherty, Allanah (January 14, 2015). "I Never Knew That These Artworks Inspired Some of the Scariest Horror Movies of All Time!". Movie Pilot. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Alan McKenzie, Hollywood Tricks of The Trade Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p.122

- ^ Kermode, Mark (2003). The Exorcist. BFI Modern Classics (2nd revised ed.). British Film Institute. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-85170-967-3. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marriott, James (2005). Horror Films. Virgin Film. Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0753509418.

- ^ "Exorcist effects man Gavira dies". BBC News. January 12, 2005. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ Lucas, Tim and Kermode, Mark. Video Watchdog Magazine, issue No. 6 (July/August 1991), pgs. 20–31, "The Exorcist: From the Subliminal to the Ridiculous"

- ^ Friedkin, William. Interviewed in Video Watchdog Magazine, issue No. 6 (July/August 1991), pg. 23, "The Exorcist: From the Subliminal to the Ridiculous"

- ^ "Dark Romance – Book of Days – The 'subliminal' demon of The Exorcist". darkromance.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ "Films that flicker: the origins of subliminal advertising myths and practices". subliminalworld.org. Archived from the original on April 1, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ McCabe 1999, p. 138.

- ^ Perkins, Will. "Dan Perri: A Career Retrospective". Art of the Title. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ Ángel Ordóñez, Miguel (May 20, 2005). "Interview with Lalo Schifrin". www.scoremagacine.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Konow 2012, p. 153.

- ^ Leinberger, Charles (2011). "Music in the Horror Film: Listening to Fear". Music, Sound and the Moving Image. 5: 101–105 – via ProQuest Central.

- ^ Sisco King, Claire (2010). "Ramblin' Men and Piano Men; Crisis of Music and Masculinity in The Exorcist". Music in the Horror Film : Listening to Fear. New York: Routledge. pp. 114–133. ISBN 9780203860311.

- ^ Lester, Paul (March 21, 2014). "Mike Oldfield: 'We wouldn't have had Tubular Bells without drugs'". The Guardian. The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ "The Exorcist Soundtrack". Discogs. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Liston, Tyler (November 9, 2017). "Waxwork Records Releases THE EXORCIST soundtrack on vinyl". Nightmare on Filmstreet. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Henze: Complete Deutsche Grammophon Recordings" Archived April 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine by Brett Allen-Bayes, Limelight, January 9, 2014

- ^ Muir 2002, p. 263.

- ^ Travers & Rieff 1974, p. 149.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Klemesrud, Judy (January 27, 1974). "They Wait Hours to Be Shocked". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "William Peter Blatty's The Exorcist - Warner Bros. Advert". Variety. January 9, 1974. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Van Gelder, Lawrence (January 24, 1974). "'Exorcist' Casts Spell on Full Houses". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ The Exorcist – Special Widescreen Edition Box Set (VHS). ISBN 6305256209 Check

|isbn=value: invalid group id (help). - ^ The Exorcist (25th Anniversary Special ed.). ISBN 079073804X.

- ^ "The Exorcist (The Version You've Never Seen)". Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Exorcist: Director's Cut (Extended Edition)". Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "Blu-ray.com". Blu-ray.com. October 20, 2008. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ "The Exorcist Announced on Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ "Full Blu-ray Details to Make Your Head Spin – The Exorcist". DreadCentral. October 4, 2012. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "The Exorcist releasing on Blu-ray in October 2010". Morehorror.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ ""THE EXORCIST EXTENDED DIRECTOR'S CUT" AVAILABLE OCTOBER 5 FROM WARNER HOME VIDEO". Warnerbros.com. June 21, 2010. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Exorcist: 40th Anniversary Edition Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. June 20, 2013. Archived from the original on June 26, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Exorcist: The Complete Anthology (The Exorcist / The Exorcist (Unrated) / Exorcist II: The Heretic / The Exorcist III / Exorcist: The Beginning/ Exorcist: Dominion)". Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Exorcist: The Complete Anthology (Blu-ray)". Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.