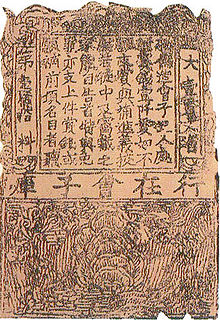

Huizi (currency)

The Huizi (simplified Chinese: 会子; traditional Chinese: 會子; pinyin: huì zi), issued in the year 1160, was the official banknote of the Chinese Southern Song dynasty. It has the highest amount of issuance among various banknote types during the Song dynasty. Huizi notes came on three-colour printed paper and their usage was heavily promoted by the government of the Southern Song dynasty, the Huizi were backed by 280,000 guàn of copper cash coins.[1]

History[]

The Huizi was originally introduced in the region of Liangzhe (兩浙) around what is present-day Zhejiang, and after 1160 Huizi notes were issued by the Ministry of Revenue (戶部) and their circulation was overseen by the Paper Notes Office (會子務). The earliest mentions of Huizi banknotes can be traced back to Shaanxi in 1075. In Hangzhou and the areas around it bianqian huizi (便錢會子) or "comfortable money" had become a common form of exchange during the beginning of the Southern Song dynasty. Besides the Jiaozi, Qianyin, and Guanzi the Huizi had become the most important form of paper currency during the Southern Song dynasty and was used for daily business transactions as well as for tax collecting and the usage of Huizi banknotes had also spread to the western and northern areas of the empire. Between the years of 1161 and 1166 the government of the Song dynasty had produced 28,000,000 dào (道, equal to a guàn or 1000 wén) in Huizi notes. During the reign of Emperor Xiaozong the usage of paper money came into question but as there was a shortage of copper cash coins they were assessed to be needed for the economy to be maintained as the amount of coins in circulation didn't sufficiently meet the markers demands, at this time there were Huizi banknotes with denominations as high as 4,900,000 guàn in daily circulation. In reaction to this Emperor Xiaozong regularly renewed the Huizi in circulation but not all expired Huizi notes were destroyed as they often kept circulated at lower values which caused the number of Huizi in circulation to rise. The Huizi notes were set to expire 3 years after their introduction and could be exchanged for their nominal value in copper cash coins, but in reality they were only produced every 9 years and 20,000,000 guàn in newly printed notes were added to the market, in 1195 this was raised to 30,000,000 guàn.

| Period | Value of Huizi in circulation |

|---|---|

| Early thirteenth century | 41,000,000 mín |

| 1209 | 115,600,000 mín |

| 1231 | 329,000,000 mín |

As Huizi notes were easily forged the currency became deprecated to the point that a banknote of 200 wén couldn't buy a single straw sandal anymore near the end of the dynasty. The value of the Huizi had lowered so much that a guàn was only accepted at between 300 and 400 cash coins, which caused people to start hoarding these coins and remove them from circulation which had a devastating effect on the economy. As the Mongols continued marching south the Chinese military required more money causing the government to print an excessive amount of Huizi banknotes.[2]

Denominations[]

The first Huizi note had a nominal value of 1 guàn, but subsequently banknotes of 200 wén, 300 wén, and 500 wén were introduced in 1163.

Regional variants[]

Other than the Huizi issued by the central government regional varieties existed such as get Hubei Huizi (湖北會子) which was produced in a volume of 7,000,000 mín but only came in the denominations 500 mín and 1000 mín, the Iron-cash Huizi (鐵錢會子) came in denominations of 100 wén, 200 wén, and 300 wén and circulated only in Jinyang, the Silver Huizi (銀會子) of Sichuan was introduced in 1137 and was denominated in 1 qián and 1.5 qián. Other variants include the Zhibian Huizi (直便會子) and the Huguang Huizi (湖廣會子).

See also[]

- Economy of the Song dynasty

- Economy of China

- Economic history of China (Pre-1911)

- Economic history of China (1912–1949)

- Southern Song dynasty coinage

References[]

- ^ "Paper Money in Premodern China.". 2000 ff. © Ulrich Theobald - ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art. 10 May 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "huizi 會子, a type of paper money.". 2000 ff. © Ulrich Theobald - ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art. 10 May 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

Sources[]

- Huang Da (黃達), Liu Hongru (劉鴻儒), Zhang Xiao (張��), ed. (1990). Zhongguo jinrong baike quanshu (中國金融百科全書) (Beijing: Jingji guanli chubanshe), Vol. 1, 89. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Li Ting (李埏) (1992). "Huizi (會子)", in Zhongguo da baike quanshu (中國大百科全書), Zhongguo lishi (中國歷史) (Beijing/Shanghai: Zhongguo da baike quanshu chubanshe), Vol. 1, 416. (in Mandarin Chinese)

- Zhou Fazeng (周發增), Chen Longtao (陳隆濤), Qi Jixiang (齊吉祥), ed. (1998). Zhongguo gudai zhengzhi zhidu shi cidian (中國古代政治制度史辭典) (Beijing: Shoudu shifan daxue chubanshe), 367. (in Mandarin Chinese)

External links[]

- Currencies of China

- Currencies of Asia

- Medieval currencies

- Banknotes of China

- Song dynasty