Hungerford massacre

| Hungerford massacre | |

|---|---|

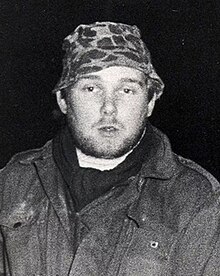

Michael Ryan in 1986 | |

| Location | Hungerford, England, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°25′N 1°31′W / 51.41°N 1.52°WCoordinates: 51°25′N 1°31′W / 51.41°N 1.52°W |

| Date | August 19, 1987 c. 12:30 p.m. – c. 6:52 p.m. |

Attack type | Mass murder, spree shooting, murder-suicide, massacre, arson |

| Weapons | Multiple firearms (see §Firearms ownership) |

| Deaths | 17 (including the perpetrator) |

| Injured | 15+ |

| Perpetrator | Michael Robert Ryan |

The Hungerford massacre was a series of random shootings in Hungerford, England, United Kingdom on 19 August 1987, when 27-year-old Michael Robert Ryan, an unemployed former labourer, shot dead 16 people, including an unarmed police officer and his own mother, before shooting himself. The shootings, committed using a handgun and two semi-automatic rifles, occurred at several locations, including a school he had once attended. Fifteen other people were also shot but survived. No firm motive for the killings has ever been established.

A report on the massacre was commissioned by Home Secretary Douglas Hurd. The Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988 was passed in the wake of the incident, which bans the ownership of semi-automatic centre-fire rifles and restricts the use of shotguns with a capacity of more than three cartridges. The shootings remain one of the deadliest firearms incidents in British history.[1]

Perpetrator[]

Michael Robert Ryan (born 18 May 1960) was born at Savernake Hospital in Marlborough, Wiltshire,[2] the only child of Alfred and Dorothy Ryan.[3] His father, Alfred Henry Ryan, was 55 years old when Michael was born. Alfred worked for a local government agency as a building inspector,[3] and died in Swindon in May 1985 at the age of 80 from cancer.[citation needed] Ryan's mother, Dorothy, was 20 years Alfred's junior and worked as a school dinner lady before taking employment at Elcot Park Hotel as a waitress.[3][4] In April 1987, Ryan began employment as a labourer working on footpaths and fences near the River Thames, approximately 20 miles (32 km) from Hungerford. He left the job in July, and returned to claiming unemployment benefits.[5]

Firearms ownership[]

Ryan was issued a shotgun certificate on 2 February 1978, and on 11 December 1986 he was granted a firearms certificate covering the ownership of two pistols.[6] The licence only permitted Ryan to use the weapons at approved ranges; his application stated that he would use them at a target shooting facility in Abingdon[6] and he was a member of a rifle club in Devizes.[7] He later applied to have the certificate amended to cover a third pistol, as he intended to sell one of the two he had acquired since the granting of the certificate (a Smith & Wesson .38-caliber revolver) and to buy two more. This was approved on 30 April 1987. On 14 July, he applied for another variation, to cover two semi-automatic rifles, which was approved on 30 July. At the time of the massacre, he was licensed to possess eight firearms, which he purchased between 17 December 1986 and 8 August 1987:[6][8]

- Beretta 9mm pistol

- shotgun

- Browning shotgun

- .22 pistol

- CZ ORSO self-loading .32 ACP pistol

- Norinco Type 56 7.62×39mm semi-automatic rifle[a]

- Underwood Carbine .30 rifle

Ryan used the Beretta pistol, the Norinco, and the Carbine in the massacre. The CZ pistol was being repaired by a dealer at the time, and he had sold the Bernadelli shortly before the shootings.[6] The Norinco was purchased from firearms dealer Mick Ranger.[9]

Ryan showed some of his firearms – as well as improvised explosive devices – to his colleagues at his labouring job. As well as his target practise at legitimate venues, Ryan used a large road sign at the junction of the M4 and the A338.[5]

Health[]

Following Ryan's death, his mental health came under analysis. John Hamilton, the medical director of Broadmoor Hospital,[10] stated that "Ryan was most likely to be suffering from acute schizophrenia. He might have had a reason for doing what he did, but it was likely to be bizarre and peculiar to him."[2] Jim Higgins, a consultant forensic psychiatrist, suspected that Ryan was psychotic, describing how "matricide is the schizophrenic crime."[2][11] A psychologist in BBC One's The Hungerford Massacre documentary described how Ryan had "anger and contempt for ordinary life".[12]

Shootings[]

Wiltshire[]

The first shooting occurred in Savernake Forest, seven miles (11 km) to the west of Hungerford. At 12:30 BST, 35-year-old Susan Godfrey and her two pre-school children had come to the area from Burghfield Common near Reading for a family picnic.[13] Ryan, openly armed, approached the family and Susan placed the children in her car. After abducting her at gunpoint, Ryan walked Godfrey 75–100 yards (69–91 m) into the forest. He had placed down a groundsheet; a police report identified the possibility that Ryan may have intended to rape Godfrey.[6][14] Godfrey's body was found approximately 10 yards (9.1 m) from the groundsheet; she had sustained 13 bullet wounds to her back and there was no evidence of sexual assault.[6] Godfrey's children were found by a woman walking in the woods.[13]

Ryan left the forest and drove east on the A4, stopping to fill both his car and a petrol can at the Golden Arrow petrol station in Froxfield. After another customer at the station left, Ryan shot at the cashier from the forecourt.[6] He entered the store and attempted to shoot her at point-blank range; this failed when his gun apparently jammed.[13] He left the petrol station and the cashier telephoned 999; this call had been preceded by another emergency call, possibly by a member of the public who believed they saw an armed robbery at the petrol station. Thames Valley Police sent three patrol cars along the A4 to investigate.[15]

Hungerford[]

South View and Fairview Road[]

After leaving Froxfield, Ryan returned to his home on South View, Hungerford. Arriving there shortly after 12:45, he was seen by neighbours who described him as looking upset. Soon after entering his house, one of the witnesses heard gunshots; Ryan had shot the two family dogs.[15] He exited the house with equipment such as ammunition, survival equipment, and a flak jacket. He failed to start his car, and instead returned to the house and set the living room alight using the petrol he purchased from Froxfield;[15] the resultant fire destroyed the house and three adjacent properties.[16] Leaving the house, he headed east on South View towards school playing fields. En route he shot and killed two of his neighbours, Roland and Sheila Mason.[2] Fourteen-year-old Lisa Mildenhall, who also lived nearby, heard the noise and went to see what it was; Ryan shot her four times in the legs.[15] She sought first aid from her mother and another nearby resident and survived.[17] Ryan was chastised by 77-year-old Dorothy Smith for "scaring everybody to death" for making noise, although he did not shoot her.[18] Ryan then shot Margery Jackson, one of the people who had seen him arrive home. She telephoned her friend George White for help, and asked him to collect her husband Ivor from work in Newbury.[18]

Past the playing fields, Ryan entered the town's common. He shot and killed 51-year-old Kenneth Clements who had been walking his dog with his family; the family escaped without injury.[18] At this time, approximately 12:50, police had linked the incident in Froxfield to the many calls they received in Hungerford and instead focused on South View.[18] Ryan returned to South View from the common, and the first police officers to arrive aimed to close both ends of the road to contain a possible gunman. These officers were unarmed, and when Ryan saw the police response he shot one of the officers, PC Roger Brereton, in the chest.[18][19] Brereton, who was in his patrol car, crashed into a telegraph pole. At 12:58, Ryan shot and killed him while he was using his radio to report an active shooter.[18][20]

Still on South View, Ryan next shot at Linda Chapman and her daughter Alison, who had just turned onto the lane in their Volvo. Both were struck, although Linda was able to reverse the car out of the road.[18][6] Ryan next opened fire on Linda Bright and Hazel Haslett in an ambulance that was responding to 999 calls on South View. Both Bright and Haslett escaped without major injury.[18] After this, two of Brereton's colleagues securing the east end of South View came upon Robert, Kenneth Clements's son, who informed them that the shooter had continued west on South View.[18] Heading to investigate, Ryan shot at the constables; one took shelter in a house and the other – with Robert Clements – drove across the common to safety. At 13:12, this officer radioed to request support from Thames Valley Police's Tactical Firearms Unit (TFU) having seen the firearms Ryan was using. The TFU was on a training exercise some 38 miles (61 km) from Hungerford, and would not have all its members respond until 14:20.[21] The officer, PC Jeremy Wood, set up a makeshift command post on the common, approximately 500 yards (460 m) from South View.[22]

Ryan next shot at George White, who had returned from Newbury having collected Margery Jackson's husband Ivor from work. Driving his Toyota into South View, Ryan shot and killed White instantly and caused severe injuries to Ivor Jackson who feigned death and survived his injuries.[21] Ryan then walked to the junction of South View and Fairview Road, where he shot and killed 84-year-old Abdul Khan who was tending his garden.[21][23] After firing at and injuring a pedestrian on Fairview Road, Ryan headed back towards the common. One of the police officers in attendance, PC Bernard Maggs, made another 999 call but by this point the telephone network had reached its capacity.[23] On South View, Ryan's mother Dorothy returned in her car to see him armed; she shouted for him to stop before he shot her four times with his Beretta, twice at point-blank range.[23][24] On heading towards the common, a resident of a parallel street shouted at Ryan to "kindly stop that racket"; he responded by shooting her in the groin.[23] At 13:18 PC Wood was joined by two armed police officers at the command post on the common. Two minutes later, they saw Ryan at the War Memorial Recreation Grounds on the edge of the common.[22]

Hungerford Common and town centre[]

Near the War Memorial Recreation Grounds, Ryan shot 26-year-old Francis Butler as he walked his dog. At this point, he discarded the Carbine, it having been useless since jamming in Froxfield.[22] A witness gave Butler first aid, but he died before an ambulance arrived.[2]

Ryan next shot at, but missed, teenager Andrew Cadle, who was on his bicycle.[2] On reaching Bulpit Lane, Ryan killed taxi driver Marcus Barnard who was en route home to see family between fares.[22] Ryan headed north on Priory Avenue, where he shot and injured John Storms who was parked in his van.[25] By this time, police had set up road diversions and some of Ryan's victims were drivers affected by these change of routes.[25] Douglas and Kathleen Wainwright, visiting their son on Priory Avenue, were forced to approach from the south, where Ryan was. Approximately 100 yards (91 m) from their destination, Ryan shot Douglas dead and injured Kathleen before non-fatally shooting at two other drivers.[26] A van entered Priory Avenue, and the occupants – Eric Vardy and Stephen Ball – were shot at; Vardy was killed.[26]

At 13:30, Ryan headed south-west towards Priory Road, shooting at houses as he passed them.[26] Using the Beretta, he shot at a passing car and fatally injured the driver, 22-year-old Sandra Hill.[27]

After shooting Hill, Ryan shot his way into a house further down Priory Road and shot the occupants, 66-year-old Jack Gibbs and his 62-year-old wife Myrtle. Jack was killed instantly, and Myrtle died two days later at the Princess Margaret Hospital in Swindon.[27][28] From the house, Ryan shot at neighbouring houses and caused injury to the occupants.[2] Ryan continued south on Priory Road where he shot once at a car driven by 34-year-old Ian Playle, who was fatally struck in the neck. His wife and their two children escaped injury; Playle died at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford two days later.[27][28]

At 13:45 the police helicopter arrived and broadcast warnings to the public.[29] One Hungerford resident heard the warning before heading to Priory Road to check on his grandchildren; he took them indoors to safety before being non-fatally shot in both the shoulder and the eye.[29] Ryan continued south east on Priory Road, firing at a house before reaching John O'Gaunt School.[29]

Suicide[]

Ryan was seen approaching the school where he had formerly been a pupil, although his precise location after approximately 13:50 was unknown.[6] At this point, the TFU secured gardens and houses in the area before surrounding the school at approximately 16:00.[30] At 16:40 they heard a gunshot within a school building and more officers went to the scene; the police first saw Ryan at the school at 17:26, shortly after he had thrown his Norinco out of a third-floor window.[6][30]

Ryan became engaged in conversation with a sergeant within the TFU and informed them of his arsenal and ammunition, claiming that he had a grenade as well as the Beretta.[30] He said that he would not exit the building until the police informed him of the welfare of his mother, and stated that "Hungerford must be a bit of a mess".[30] The sergeant said he understood Ryan when he claimed that his mother's death was "a mistake"; Ryan reportedly replied, "How can you understand? I wish I had stayed in bed."[30] He later shouted, "It's funny. I killed all those people, but I haven't the guts to blow my own brains out." At 18:52, after a few minutes of silence, a muffled shot was heard from the school building; Ryan was subsequently unresponsive to police. Shortly after 20:00, armed police entered a barricaded school room to find Ryan below the window having shot himself in the right temple.[30]

Police response[]

Hungerford was policed by two sergeants and twelve constables, and on the morning of 19 August 1987 the duty cover for the section consisted of one sergeant, two patrol constables and one station duty officer.[31] A number of factors hampered the police response:[20]

- The telephone exchange could not handle the number of 999 calls made by witnesses.

- The Thames Valley firearms squad were training 40 miles (64 km) away.

- The police helicopter was in for repair, though it was eventually deployed.

- Only two phone lines were in operation at the local police station, which was undergoing renovation.

Official report[]

The Hungerford Report was commissioned by Home Secretary Douglas Hurd from the Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police, Colin Smith. Ryan's collection of weapons had been legally licensed, according to the Report. The Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988,[32] which was passed in the wake of the massacre, bans the ownership of semi-automatic centre-fire rifles and restricts the use of shotguns with a capacity of more than three cartridges (in magazine plus the breech).

Notoriety[]

The Hungerford massacre remains, along with the 1996 Dunblane school massacre, and the 2010 Cumbria shootings, one of the worst criminal atrocities involving firearms to occur in the United Kingdom. The Dunblane and Cumbria shootings had a similar number of fatalities, and in both cases the perpetrators killed themselves. Only one person died in the 1989 Monkseaton shootings, but 14 others were wounded, and the perpetrator did not kill himself.

In the days following the massacre, the British tabloid press was filled with stories about Ryan's life. Press biographies all stated that he had a near-obsessive fascination with firearms. The majority claimed that Ryan had possessed magazines about survival skills and firearms, Soldier of Fortune[33] being frequently named.

Cultural references[]

In literature[]

- J. G. Ballard's novel, Running Wild, centres on the fictitious Richard Greville, a Deputy Psychiatric Advisor with the Metropolitan Police Service who authored "an unpopular minority report on the Hungerford killings" and is sent to investigate mass murder in a gated community[34]

- The Hungerford massacre inspired Christopher Priest's 1998 novel The Extremes[35]

In music[]

- "Sulk", the penultimate track on Radiohead's album The Bends, was written as a response to the massacre[36]

In television[]

See also[]

- List of massacres in Great Britain

- List of rampage killers

- Hoddle Street massacre

- Port Arthur massacre (Australia), a similar spree killing in Australia in 1996 which prompted similar gun law reforms

- Ughill Hall shootings, which occurred eleven months earlier in Sheffield

- Southcliffe

Footnotes[]

- ^ The Type 56 was described as a Kalashnikov AK-47 copy, and was identified as a Kalashnikov in the report from Thames Valley Police to the Home Secretary[6]

References[]

- ^ "BBC: On this Day". 19 August 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Josephs, Jeremy. "Hungerford: One Man's Massacre". Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 161. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 162. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 164. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Smith, Colin. "SHOOTING INCIDENTS AT HUNGERFORD ON 19 AUGUST 1987 REPORT OF MR COLIN SMITH CVO QPM. CHIEF CONSTABLE THAMES VALLEY POLICE TO THE RT HON DOUGLAS HURD CBE, MP. SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT". Archived from the original on 22 January 2005.

- ^ Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 167. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Cheston, Paul (20 July 2012). "Arms dealer who sold rifle used in Hungerford massacre jailed for". www.standard.co.uk. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Barnett, Antony (27 April 2003). "Exposed: Global dealer in death". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "OBITUARY: J R Hamilton". British Medical Journal. 301: 116. 14 July 1990. doi:10.1136/bmj.301.6743.116. S2CID 220192073. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Thorson, Larry (20 August 1987). "Britain's Worst Mass Murderer a Polite Loner With AM-Britain-Shooting Bjt". AP NEWS. Associated Press. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Smith, Rupert (8 December 2004). "TV review". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. pp. 168–169. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ "Massacre". BBC. BBC. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 170. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ "The Crimes – Michael Ryan and the Hungerford Massacre on Crime and Investigation Network". Crimeandinvestigation.co.uk. 19 August 1987. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Parry, Gareth (20 August 1987). "Gunman in combat gear kills himself after 14 die in shooting spree". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 172. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ "Michael Ryan, the Hungerford UK Mass Murderer – Whatever Moves – Crime Library on". Trutv.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grice, Elizabeth (7 December 2004). "Ryan shot at me, then at my mother". London: The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 May 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 173. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 177. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 174. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine. "Terror in Hungerford". Crime Library: Criminal Minds and Methods. TruTV. p. 7. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 178. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 179. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 180. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Glasgow Herald – Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 182. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Mass Murderers. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 184. ISBN 9780783500041.

- ^ The Hungerford Report – Shooting Incidents At Hungerford On 19 August 1987, Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police Colin Smith to Home Secretary Douglas Hurd Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988 (c. 45). Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ^ – Errol Mason (1993). "Critical Factors in Firearms Control" (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. p. 209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2005.

- ^ Grossberg, Lawrence, ed. (1992). Cultural studies. New York. p. 220. ISBN 0415903459.

- ^ Charles Platt (2017). Dream Makers. Orion. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-4732-1968-7.

- ^ Randall, Mac (2004). Exit music : the Radiohead story. London: Omnibus. p. 119. ISBN 1-84449-183-8.

- ^ Syal, Rajeev (8 February 2004). "Hungerford outrage at TV documentary". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

Sources[]

- M. Barker and J. Petley (eds) (26 April 2001). Ill Effects: The Media Violence Debate (Communication & Society. Routledge; 2Rev Ed editio. pp. 63–77. ISBN 0-415-22513-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Webster, Duncan (May 1989). "Whodunnit? America did: Rambo and post-Hungerford rhetoric". Cultural Studies. Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group. 3 (2): 173. doi:10.1080/09502388900490121.

- 1987 in England

- 1987 mass shootings

- 1987 murders in the United Kingdom

- 1980s in Berkshire

- 1980s mass shootings in the United Kingdom

- Massacres in the 1980s

- 20th century in Wiltshire

- 20th-century mass murder in England

- August 1987 crimes

- August 1987 events in the United Kingdom

- Crime in Wiltshire

- Deaths by firearm in England

- History of mental health in the United Kingdom

- Hungerford

- Mass murder in 1987

- Mass shootings in England

- Massacres in England

- Matricides

- Murder in Berkshire

- Murder–suicides in the United Kingdom

- Spree shootings in the United Kingdom

- Suicides by firearm in England