Swindon

| Swindon | |

|---|---|

Swindon town centre seen from Radnor Street Cemetery | |

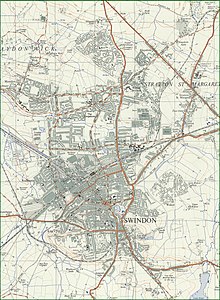

Swindon Location within Wiltshire | |

| Population | 185,600 (built-up area in 2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SU152842 |

| • London | 71 miles (114 km) |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SWINDON |

| Postcode district | SN1–SN6, SN25, SN26 |

| Dialling code | 01793 |

| Police | Wiltshire |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Borough Council |

Swindon (/ˈswɪndən/ (![]() listen)) is a large town in Wiltshire, South West England, lying between Bristol, 35 miles (56 kilometres) to the west, and Reading, the same distance to the east. The town is 71 miles (114 km) west of London. The population of the Swindon built-up area was 185,600 in 2011.[1]

listen)) is a large town in Wiltshire, South West England, lying between Bristol, 35 miles (56 kilometres) to the west, and Reading, the same distance to the east. The town is 71 miles (114 km) west of London. The population of the Swindon built-up area was 185,600 in 2011.[1]

The Town Development Act 1952 led to a major increase in its population.[2]

Swindon railway station is on the line from London Paddington to Bristol. Swindon Borough Council is a unitary authority, independent of Wiltshire Council since 1997. Residents of Swindon are known as Swindonians. The town is home to the English Heritage National Monument Record Centre and the headquarters of the National Trust (both on parts of the site of the former Great Western Railway's Swindon Works), and the head office of the Nationwide Building Society.

History[]

Early history[]

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Swindon sat in a defensible position atop a limestone hill. It is referred to in the 1086 Domesday Book as Suindune,[3] believed to be derived from the Old English words "swine" and "dun" meaning "pig hill" or possibly Sweyn's hill, Sweyn being a Scandinavian name akin to Sven and English swain, meaning a young man.

Swindon is recorded in the Domesday Book as a manor in the hundred of , Wiltshire. It was one of the larger manors, recorded as having 27 households and a rent value of £10 14s, which was divided among five landlords.[3] Before the Battle of Hastings the Swindon estate was owned by an Anglo-Saxon thane called Leofgeat.[4] After the Norman Conquest, Swindon was split into five holdings: the largest was held between Miles Crispin and Odin the Chamberlain,[3] and the second by Wadard, a knight in the service of Odo of Bayeux, brother of the king.[4] The manors of Westlecot, Walcot, Rodbourne, Moredon and Stratton are also listed; all are now part of Swindon.

The Goddard family were lord of the manor from the 16th century for many generations, living at the manor house, sometimes known as The Lawn.

Swindon was a small market town, mainly for barter trade, until roughly 1848. This original market area is on top of the hill in central Swindon, now known as Old Town.[5]

The Industrial Revolution was responsible for an acceleration of Swindon's growth. Construction of the Wilts and Berks Canal in 1810 and the North Wilts Canal in 1819 brought trade to the area, and Swindon's population started to grow.

Railway town[]

Between 1841 and 1842, Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Swindon Works was built for the repair and maintenance of locomotives on the Great Western Railway (GWR). The GWR built a small railway village to house some of its workers. The Steam Railway Museum and English Heritage, including the English Heritage Archive, now occupy part of the old works. In the village were the GWR Medical Fund Clinic at Park House and its hospital, both on Faringdon Road, and the 1892 health centre in Milton Road, which housed clinics, a pharmacy, laundries, baths, Turkish baths and swimming pools, was almost opposite.

From 1871, GWR workers had a small amount deducted from their weekly pay and put into a healthcare fund; GWR doctors could prescribe them or their family members free medicines or send them for medical treatment. In 1878 the fund began providing artificial limbs made by craftsmen from the carriage and wagon works, and nine years later opened its first dental surgery. In his first few months in post, the dentist extracted more than 2,000 teeth. From the opening in 1892 of the health centre, a doctor could also prescribe a haircut or even a bath. The cradle-to-grave extent of this service was later used as a blueprint for the NHS.[6]

The Mechanics' Institute, formed in 1844, moved into a building that looked rather like a church and included a covered market, on 1 May 1855. The New Swindon Improvement Company, a co-operative, raised the funds for this programme of self-improvement and paid the GWR £40 a year for its new home on a site at the heart of the railway village. It was a groundbreaking organisation that transformed the railway's workforce into some of the country's best-educated manual workers.[7]

The Mechanics' Institute had the UK's first lending library,[8] and a range of improving lectures, access to a theatre and various other activities, such as ambulance classes and xylophone lessons. A former institute secretary formed the New Swindon Co-operative Society in 1853 which, after a schism in the society's membership, spawned the New Swindon Industrial Society, which ran a retail business from a stall in the market at the institute. The institute also nurtured pioneering trades unionists and encouraged local democracy.[9]

When tuberculosis hit the new town, the Mechanics' Institute persuaded the industrial pioneers of North Wiltshire to agree that the railway's former employees should continue to receive medical attention from the doctors of the GWR Medical Society Fund, which the institute had played a role in establishing and funding.[10]

Swindon's 'other' railway, the Swindon, Marlborough and Andover Railway, merged with the Swindon and Cheltenham Extension Railway to form the Midland & South Western Junction Railway, which set out to join the London & South Western Railway with the Midland Railway at Cheltenham. The Swindon, Marlborough & Andover had planned to tunnel under the hill on which Swindon's Old Town stands but the money ran out and the railway ran into Swindon Town railway station, off Devizes Road in the Old Town, skirting the new town to the west, intersecting with the GWR at Rushey Platt and heading north for Cirencester, Cheltenham and the LMS, whose 'Midland Red' livery the M&SWJR adopted.

During the second half of the 19th century, Swindon New Town grew around the main line between London and Bristol. In 1900, the original market town, Old Swindon, merged with its new neighbour at the bottom of the hill to become a single town.[5]

On 1 July 1923, the GWR took over the largely single-track M&SWJR and the line northwards from Swindon Town was diverted to Swindon Junction station, leaving the Town station with only the line south to Andover and Salisbury.[11][12][13] The last passenger trains on what had been the SM&A ran on 10 September 1961, 80 years after the railway's first stretch opened.

During the first half of the 20th century, the railway works was the town's largest employer and one of the biggest in the country, employing more than 14,500 workers. Alfred Williams[14] (1877–1930) wrote about his life as a hammerman at the works.[15]

The works' decline started in 1960, when it rolled out Evening Star, the last steam engine to be built in the UK.[16] The works lost its locomotive building role and took on rolling stock maintenance for British Rail. In the late 1970s, much of the works closed and the rest followed in 1986.

The community centre in the railway village was originally the barrack accommodation for railway employees of the GWR. The building became the Railway Museum in the 1960s, until the opening of the STEAM Museum in the 2000s.

Modern period[]

The Second World War saw an influx of new industries as part of the war effort; Vickers-Armstrong making aircraft at Stratton, and Plesseys at Cheney Manor producing electrical components. By 1960 Plessey had become Swindon's biggest employer, with a predominantly female workforce.[17] David Murray John, Swindon's town clerk from 1938 to 1974, is seen as a pioneering figure in Swindon's post-war regeneration: his last act before retirement was to sign the contract for Swindon's tallest building, which is now named after him.[18] Murray John's successor was David Maxwell Kent, appointed by the Swindon/Highworth Joint Committee in 1973: he had worked closely with Murray John and continued similar policies for a further twenty years. The Greater London Council withdrew from the Town Development Agreement and the local council continued the development on its own.

There was the problem of the Western Development and of Lydiard Park being in the new North Wiltshire district, but this was resolved by a boundary change to take in part of North Wiltshire. Another factor limiting local decision-taking was the continuing role of Wiltshire County Council in the administration of Swindon. Together with like-minded councils, a campaign was launched to bring an updated form of county borough status to Swindon. This was successful in 1997 with the formation of Swindon Borough Council, covering the area of the former Thamesdown and the former Highworth Rural District Council.

The closure of the railway works (which had been in decline for many years) was a major blow to Swindon.[citation needed] Because of this and the major growth in population, diversification was continued at a rapid pace and the town now has all the features of a successful urban/rural council in the Outer southeast zone.

In February 2008 The Times named Swindon as one of "The 20 best places to buy a property in Britain".[19] Only Warrington had a lower ratio of house prices to household income in 2007, with the average household income in Swindon among the highest in the country.

In October 2008 Swindon made a controversial move to ban fixed point speed cameras. The move was branded as reckless by some[20] but by November 2008 Portsmouth, Walsall, and Birmingham councils[21][22] were also considering the move.

In 2001 construction began on Priory Vale, the third and final instalment in Swindon's 'Northern Expansion' project, which began with Abbey Meads and continued at St Andrew's Ridge. In 2002 the New Swindon Company was formed with the remit of regenerating the town centre, to improve Swindon's regional status.[23] The main areas targeted were Union Square, The Promenade, The Hub, Swindon Central, North Star Village, The Campus, and the Public Realm.

In August 2019 a secondary school in the town was at the centre of a 'county lines' drug supply investigation by Wiltshire Police, with 40 pupils suspected of being involved in the supply of cannabis and cocaine, and girls as young as 14 being coerced into sexual activity in exchange for drugs.[24]

Governance[]

The local council was created in 1974 as the Borough of Thamesdown, out of the areas of Swindon Borough and Highworth Rural District. It was not initially called Swindon, because the borough covers a larger area than the town; it was renamed as the Borough of Swindon in 1997. The borough became a unitary authority on 1 April 1997,[25] following a review by the Local Government Commission for England. The town is therefore no longer under the auspices of Wiltshire Council.

The executive comprises a leader and a cabinet, currently made up from the Conservative Group. The council as of the 2016 election has a majority of Conservative councillors.[26]

Swindon is represented in the national parliament by two MPs. Robert Buckland (Conservative) was elected for the South Swindon seat in May 2010 with a 5.5% swing from Labour and Justin Tomlinson, also Conservative, represents North Swindon after a 10.1% swing at the same election. Both retained their seats at the 2015 and 2017 elections.[27] Prior to 1997 there was a single seat for Swindon, although much of what is now in Swindon was then part of the Devizes seat.

Geography[]

Swindon is a town in northeast Wiltshire, 35 miles (56 km) west-northwest of Reading and the same distance east-northeast of Bristol 'as the crow flies'.[28][29] The town is also 26 miles (42 km) southwest of Oxford, 65 miles (104 km) south-southeast of Birmingham, 71 miles (114 km) west of London and 60 miles (98 km) east of Cardiff. Swindon town centre is also equidistant from the county boundaries of Berkshire and Gloucestershire, both being 8 miles (13 km) away. The border with Oxfordshire is slightly closer, being around 5 miles (8 km) away.

Swindon is within a landlocked county and is a considerable distance from any coastline. The nearest section of coast on the English Channel is near Christchurch, 56 miles (90 km) due south. Meanwhile, the eastern limit of the Bristol Channel, just north of Weston-super-mare, lies 53 miles (85 km) to the west.

The landscape is dominated by the chalk hills of the Wiltshire Downs to the south and east. The Old Town stands on a hill of Purbeck and Portland stone; this was quarried from Roman times until the 1950s. The area that was known as New Swindon is made up of mostly Kimmeridge clay with outcrops of Corrallian clay in the areas of Penhill and Pinehurst. Oxford clay makes up the rest of the borough.[30] The River Ray rises at Wroughton and forms much of the borough's western boundary, joining the Thames which defines the northern boundary, and the source of which is located in nearby Kemble, Gloucestershire. The River Cole and its tributaries flow northeastward from the town and form the northeastern boundary.

- Nearby towns: Calne, Chippenham, Royal Wootton Bassett, Cirencester, Cricklade, Devizes, Highworth, Marlborough and Malmesbury

- Nearby villages: Badbury, Blunsdon, Broad Hinton, Chiseldon, Hook, Liddington, Lydiard Millicent, Lyneham, Minety, Purton, South Marston, Wanborough, Wroughton

- Nearby places of interest: Avebury, Barbury Castle, Crofton Pumping Station, Lydiard Country Park, Silbury Hill, Stonehenge, Uffington White Horse

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Swindon include Coate Water, Great Quarry, Haydon Meadow, Okus Quarry and Old Town Railway Cutting

Climate[]

Swindon has an oceanic climate (Cfb in the Köppen climate classification), like the vast majority of the British Isles, with cool winters and warm summers. The nearest official weather station is RAF Lyneham, about 10 miles (16 km) west southwest of Swindon town centre. The weather station's elevation is 145 metres, compared to the typical 100 metres encountered around Swindon town centre, so is marginally cooler throughout the year.

The absolute maximum is 34.9 °C (94.8 °F)[31] recorded during August 1990. In an average year the warmest day should reach 28.7 °C (83.7 °F)[32] and 10.3 days[33] should register a temperature of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or above

The absolute minimum is −16.0 °C (3.0 °F),[34] recorded in January 1982, and in an average year 45.2 nights of air frost can be expected.

Sunshine, at 1565 hours a year, is typical for inland parts of Southern England, although significantly higher than most areas further north.

Annual rainfall averages slightly under 720 mm (28 in) per year, with 123 days reporting over 1 mm of rain.

| hideClimate data for Lyneham, elevation 145m, 1971–2000, extremes 1960– | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

32.7 (90.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.9 (94.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

34.9 (94.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16 (3) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−8 (18) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−14 (7) |

−16 (3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70.1 (2.76) |

50.6 (1.99) |

58.3 (2.30) |

47.7 (1.88) |

51.8 (2.04) |

58.5 (2.30) |

47.2 (1.86) |

56.1 (2.21) |

63.9 (2.52) |

70.4 (2.77) |

66.9 (2.63) |

77.4 (3.05) |

719.0 (28.31) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.2 | 72.3 | 108.5 | 156.9 | 196.2 | 194.1 | 212.4 | 197.5 | 144.6 | 107.3 | 71.7 | 48.4 | 1,565 |

| Source 1: Met Office[35] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[36] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

The 2011 census recorded a population of 209,156 people in the Swindon unitary authority area (including the town's urban area, Highworth, and other nearby parishes), with a 50/50 balance of males and females.[37] By mid-2019, the estimated population of the unitary authority area was 222,193.[38]

As of 2011, 57.5% of Swindonians identify themselves as Christians, a reduction from 70% in 2001. This is followed by those of no religion (31%), Muslims (1.7%), Sikhs (0.6%), Hindus (1.2%), other (0.5%) and Judaism (0.1%).[37]

In 2015, Public Health England found that 70.4% of the population was either overweight or obese with a BMI greater than 25.[39]

In 2011, the area of the town was 46.2 km2 (17.8 sq mi)[40] or 3,949 inhabitants per square kilometre (10,230/sq mi).

| Ethnic Groups 2011 | Swindon Town | Borough of Swindon |

|---|---|---|

| White British | 83.3% | 84.6% |

| Asian | 7.0% | 6.4% |

| Black | 1.5% | 1.4% |

In 2011, 16.7% of the population of Swindon were non-White British compared with 15.4% in the surrounding borough. There was also little difference between the percentages of Black and Asian residents. Swindon is one of the most ethnically diverse towns in South West England: 4.6% of the population registered themselves as 'Other White' and 2.5% of the population was either mixed race or of another ethnicity. The most ethnically diverse areas outside the town centre are to the north and east, such as Eastcott, Walcot and Gorse Hill.[citation needed]

There are three definitions of the town of Swindon for statistical purposes.[41] The most accurate and widely accepted is the Built Up Area Subdivision, which had a population of 182,441 in 2011. Another definition is the Built Up Area, with a slightly higher population of 185,609 which includes outlying areas not often referred to as being part of the town, such as Wanborough. The final definition is the unparished area, with a population of 122,642. As its name suggests it reflects the former unparished area, now covered by the parishes of West Swindon, Central Swindon North and South, and Nythe, Eldene and Liden; thus it omits suburbs to the east and north, namely the parishes of Covingham, Stratton St Margaret and Haydon Wick.[42]

St Helena community[]

By 2018, Swindon had a concentration of people originating from Saint Helena. Therefore, it got the nickname "Swindolena", and people of St Helena origin celebrate St Helena Sport Day.[43]

Polish community[]

After the end of World War II, Polish refugees were temporarily housed in barracks at RAF Fairford, about 25 km (16 mi) to the north. Around 1950, some settled in Scotland and others in Swindon[44] rather than stay in the barracks or hostels they were offered.[45]

The 2001 UK Census found that most of the Polish-born people had stayed or returned after serving with British forces during World War II. Swindon and Nottingham were parts of this settlement.[46] Data from that census showed that 566 Swindonians were Polish-born.[47] Notes to those data read: ‘The Polish Resettlement Act of 1947, which was designed to provide help and support to people who wished to settle here, covered about 190,000 people ... at the time Britain did not recognise many of the professional [qualifications] gained overseas ... [but] many did find work after the war; some went down the mines, some worked on the land or in steelworks. Housing was more of a problem and many Poles were forced to live in barracks previously used for POWs ... The first generation took pains to ensure that their children grew up with a strong sense of Polish identity.'

In 2004,[out of date] NHS planners devising services for senior citizens estimated that 5% of Swindon's population were not 'ethnically British'[48] and most of those were culturally Polish.

The town's Polish ex-servicemen's club, which had run a football team for 45 years, closed in 2012. Barman Jerzy Trojan blamed the decline of both club and team on the children and grandchildren of the original refugees losing their Polish identity.[45]

Places of worship[]

There are numerous places of worship in Swindon, some of which are listed buildings.[49] Until 1845, the only church in Swindon was the Holy Rood Church, a Grade II listed building.[50] That year, St Mark's Church was built. In 1851, Christ Church was built. Later in the year, the first Roman Catholic chapel was opened in the town and was also named Holy Rood. In 1866, Cambria Baptist Chapel was built. In the 1880s, Bath Road Methodist Chapel was built. In 1885, St Barnabas Church was built. In 1907, St Augustine's Church in Even Swindon was built. Various churches and places of worship were built in the town by other denominations and faiths.[51]

Economy[]

Major employers in the town include BMW/Mini (formerly Pressed Steel Fisher) in Stratton, Dolby Labs, international engineering consultancy firm Halcrow, and retailer W H Smith's distribution centre and headquarters. The electronics company Intel has its European head office on the south side of the town. Insurance and financial services companies such as Nationwide Building Society and Zurich Financial Services, the energy companies RWE Generation UK plc and Npower (a company of the Innogy group), the fuel card and fleet management company Arval, pharmaceutical companies such as Canada's Patheon and the United States-based Catalent Pharma Solutions and French medical supplies manufacturer Vygon (UK) Ltd have their UK divisions headquartered in the town. Swindon also has the head office of the National Trust and the head office of the UK Space Agency. Other employers include all of the national Research Councils, the British Computer Society, TE Connectivity, Lok'nStore and consumer goods supplier Reckitt Benckiser.

From 1985 to 2021, Japanese car manufacturer Honda had its sole UK plant at South Marston, just outside Swindon.[52] In March 2021, it was announced that logistics firm Panattoni will move to the former Honda site.

Previously Swindon was a centre of excellence for 3G and 4G mobile telecommunications research and development for Motorola, Alcatel, Lucent Technologies, Nokia Siemens Networks and Cisco.

Transport[]

At the junction of two Roman roads, the town has developed into a transport hub over the centuries. It is on the historical GWR and on canals. It also has two junctions (15 and 16) on the M4 motorway.

Swindon railway station opened in 1842 as Swindon Junction, and until 1895 every train stopped for at least 10 minutes to change locomotives. As a result, the station hosted the first recorded railway refreshment rooms.[53]

Swindon bus operators are Thamesdown and Stagecoach. The former Stagecoach Bus Depot on Eastcott Road has been approved for development as a housing site.[54]

Swindon is one of the locations for an innovative scheme called Car share. It was set up as a joint venture between Wiltshire County Council and a private organisation and now has over 300,000 members registered. It is a car pool or ride-sharing rather than a car share scheme, seeking to link people willing to share transport.

The town contains a large roundabout called Magic Roundabout. There are five mini-roundabouts within this roundabout and at its centre is a contra-rotational hub.[55] It is the junction of five roads: (clockwise from South) Drove Road, Fleming Way, County Road, Shrivenham Road and Queens Drive. It is built on the site of Swindon wharf on the abandoned Wilts & Berks Canal, near the County Ground. The official name used to be County Islands, although it was colloquially known as the Magic Roundabout and the official name was changed in the late 1990s[citation needed] to match its nickname.

On 8 October 2019, GWR posted a modern speed record when an Intercity Express Train took just 44 minutes to travel from Swindon to London Paddington.[56]

Tourism and recreation[]

Events[]

Annual events in Swindon include:

- The Swindon Festival of Literature, held over two weeks in May.

- The Swindon Mela, an all-day celebration of South Indian arts and culture in the Town Gardens, which attracts up to 10,000 visitors each year.[57]

- The Children's Fete, a town-wide event in celebration of Swindon's children, community, culture, and heritage, is usually held the first Saturday in July in the GWR Park on Faringdon Road, with 8,000 attending in 2016.

- The Summer Breeze Festival has been held annually in the town since 2007[58] with headliners including Toploader[59] and KT Tunstall.[60] The family-friendly music event is run by volunteers on a non-profit basis with any funds raised going to charity.

- An annual Gay Pride Parade called Swindon And Wiltshire Pride is held in the town. The parade has been held in the Town Gardens since 2007. Swedish DJ Basshunter performed in the 2012 celebrations, with around 8,000 people attending.

- The Swindon Beer Festival, Organised by the local branch of the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA), is held at the STEAM museum in October each year. There is also an Old Town Beer Festival held at Christ Church on the 11 and 12 May annually.

Arts venues[]

- Swindon's most recent addition is the Shoebox Theatre, a fringe theatre and producing house with a focus on contemporary performance and new work.

- Live music venues such as Baila Coffee & Vinyl, The Castle, The Beehive, Level III, and The Victoria attract local acts as well as touring national acts. Collectively they host an annual music festival, the Swindon Shuffle.[61] The Oasis Leisure Centre and the County Ground are used for some major events. MECA is a 2,000-capacity music venue in the former Mecca bingo hall.

- The Arts Centre is a theatre in Old Town which seats 200 and has music, professional and amateur theatre, comedians, films, children's events, and one-man shows.

- The Wyvern Theatre has film, comedy, and music.

- In 2012 Swindon: The Opera was performed at the STEAM Museum in Swindon by the Janice Thompson Performance Trust,[62] after a successful 2011 Jubilee People's Millions Lottery bid. It charted Swindon's history since 1952 until the present day. Over twenty songs were written by Matt Fox, with music by internationally acclaimed composer Betty Roe MBE.

Shopping / Plazas[]

- Swindon Designer Outlet is an indoor shopping mall for reduced-price goods (mainly clothing), most of the buildings it uses were former railway works. The outlet is adjacent to the Steam Museum and the National Trust headquarters. It holds around 100 retailers and restaurants, and once held the record of biggest covered designer outlet centre in Europe.[63] The outlet received a significant expansion in the mid-2010s, allowing it to hold more retailers and restaurants, as well as a visual upgrade.

- The Brunel Centre and The Parade are the two shopping complexes in the town centre, built along the line of the filled-in Wilts and Berks Canal (where a canal milepost can still be seen). The Brunel Centre opened a food court called The Crossing in April 2018.[64]

- Greenbridge Retail and Leisure Park (Stratton St. Margaret), Orbital Shopping Park (Haydon Wick), and the West Swindon Shopping Centre / Shaw Ridge Leisure Park are the three major out-of-town facilities. There is also the Bridgemead Retail Park and Mannington Retail Park both located in West Swindon, in close proximity to each other. Outside of these, there are various minor retail parks.

- Regent Circus opened in 2015 on the site of a former Swindon College building. It contains a Cineworld cinema and four restaurants: Nandos, Prezzo, Ask Italian and Lamaya.

Former

- Swindon Tented Market, in the Town Centre close to the Brunel Centre, was built in 1994. It reopened in October 2009, having been closed for two years[65] but closed again in August 2017.[66]

Green spaces[]

Public parks include Lydiard Country Park, Shaw Forest Country Park, The Lawns, Stanton Park, Queens Park, Town Gardens, Pembroke Gardens and Coate Water.

Media[]

Online[]

Swindon has many online media outlets with the largest being the Swindon Advertiser. SwindonWeb was the first website dedicated to Swindon in 1997 followed by SwindonLink and The Swindonian with many other sites now available, including Total Swindon.

Print[]

Swindon has a daily newspaper, the Swindon Advertiser, with daily circulation of about 4,000 with an estimated readership of 21,000. Other newspapers covering the area include Bristol's daily Western Daily Press and the Swindon Advertisers weekly, the Gazette and Herald; the Wiltshire Ocelot (a free listings magazine), The Swindonian Monthly Magazine Swindon Star, Hungry Monkeys (a comic), Stratton Outlook, Frequency (an arts and cultural magazine), Great Swindon Magazine, Swindon Business News, Swindon Link and Highworth Link.

Radio[]

The first commercial radio station launched in Swindon was Wiltshire Radio in 1982, with BBC Wiltshire Sound launched in 1989. Wiltshire Radio later changed to GWR FM, then to Heart Wiltshire, and is now Heart West, broadcasting from studios in Bristol.[67] An alternative commercial radio station, Brunel FM, was launched in 2006 and replaced in turn by Total Star Swindon, More Radio, Jack FM and Sam FM; the frequency is now used by the Greatest Hits Radio national network.[68] Another independent station called Swindon FM was also on the air between 2001 and 2006.

Since 2008, the town has had its own 24-hour community radio station, Swindon 105.5, which was given the Queen's Award for Voluntary Service in 2014, the highest award which can be given to a voluntary group.[69] In regards to the wider Wiltshire county, the public-sector station BBC Radio Wiltshire remains based in Swindon.[70]

Television[]

The Swindon area is in the overlap between two transmission regions, the Thames valley and the West of England. ITV regional news programmes come from ITV News Meridian (with offices at Abingdon) and ITV West Country (Bristol). On BBC One the area is served by both South Today (from Oxford) and Points West (Bristol).

Between 1973 and 1982, the town had its own cable television channel called Swindon Viewpoint. This was a community television project run mainly by enthusiasts from studios in Victoria Hill, and later by Media Arts at the Town Hall Studios. It was followed by the more commercial Swindon's Local Channel, which included pay-per-view films.[71] NTL (later Virgin Media) took over the channel's parent company, ComTel, and closed the station.

Education[]

The borough of Swindon has many primary schools, 12 secondary schools, and two purpose-built sixth-form colleges. Two secondary schools also have sixth forms. There is one independent school, Maranatha Christian School at Sevenhampton.

Secondary schools[]

- Abbey Park School ages 11 – 16

- Commonweal School ages 11 – 18

- NEW BUILD – year 7 (ages 11 – 12 only in 2019/2020)

- The Dorcan Academy ages 11 – 16

- Highworth Warneford School ages 11 – 16

- Kingsdown School ages 11 – 16

- Lawn Manor Academy ages 11 – 16

- Lydiard Park Academy ages 11 – 18

- Nova Hreod Academy ages 11 – 16

- The Ridgeway School & Sixth Form College ages 11 – 18

- St. Joseph's Catholic College ages 11 – 16

- Swindon Academy ages 3 – 18

- UTC Swindon ages 14 – 18

Further education[]

New College and Swindon College cater for the town's further education and higher education requirements, mainly for 16- to 21-year-olds. Swindon College is one of the largest FE-HE colleges in southwestern England, situated at a purpose-built campus in North Star, Swindon.

Swindon also has a foundation learning programme called Include, which is situated in the Gorse Hill area. This is for 16- to 19-year-olds who are currently not in education, employment or training.

Higher education[]

Swindon is the UK's largest centre of population without its own university (by comparison, there are two universities in nearby Bath, which is half Swindon's size). In March 2008, a proposal was made by former Swindon MP, Anne Snelgrove, for a university-level institution to be established in the town within a decade, culminating in a future 'University of Swindon' (with some[who?] touting the future institution to be entitled 'The Murray John University, Swindon', after the town's most distinguished post-war civic leader). In October 2008, plans were announced for a possible University of Swindon campus to be built in east Swindon to the south of the town's Great Western Hospital, close to the M4-A419 interchange. However, these plans are currently[when?] mothballed.

Oxford Brookes University has had a campus in Swindon since 1999. The campus offers degrees in Adult Nursing and Operating Department Practice (ODP).[72] The Joel Joffe Building[73] opened in August 2016 and was officially opened[74] in February 2017 by Lord Joel Joffe, a long-time Swindon resident and former human rights lawyer. From 1999 to 2016 the Ferndale Campus was based in north-central Swindon. The main OBU campus is about 27 miles (43 km) northeast of Swindon. The university also sponsors UTC Swindon, which opened in 2014 for students aged 14–19.

Between 2000 and 2008 the University of Bath had a campus in Walcot, east Swindon.

Museums and cultural institutions[]

- National Museum of Science & Industry, Wroughton.

- Richard Jefferies Museum, dedicated to the memory of one of England's most individual writers on nature and the countryside.

- Steam Railway Museum.

- , Central Library. Extensive local studies and family history archive.

- Swindon Arts Centre, a 212-seat entertainment venue in the Old Town.

- Wyvern Theatre, the town's principal stage venue.[75]

- Swindon Museum and Swindon Art Gallery, next to each other.

- The Museum of Computing the first computer museum in the UK.

Sports[]

Football[]

Swindon Town F.C. play at the County Ground near the town centre. They have been Football League members since joining the then-new Third Division (southern section) in 1920, and won promotion to the Second Division for the first time in 1963. They won their only major trophy to date, the Football League Cup, in 1969 beating Arsenal 3–1, and won the Anglo-Italian Cup the following year as the Football Association forbade Swindon from competing in the European Cup because they were in Division 3. They won promotion to the First Division in 1990, but stayed in the Second Division due to financial irregularities, and reached the top flight (by then the Premier League) three years later. Their spell in the top flight lasted just one season, and then came a second successive relegation. A brief recovery saw them promoted at the first attempt as champions of the new Division Two, but they were relegated again four years later and in 2006 fell back into the fourth tier for the first time since 1986, although promotion was gained at the first attempt. They were relegated again four years later. Under the charismatic reign of manager Paolo Di Canio, Swindon became League Two champions in 2011–12 and played in League One, the third-highest tier until the season of 2016–17, when they were relegated to League Two after losing their penultimate game against Scunthorpe 2–1.

The town also has a non-league club Swindon Supermarine F.C., playing in Southern League Division One South and West. Nearby Highworth Town F.C., based in Highworth, also play in the Southern League whilst Royal Wootton Bassett Town F.C., Shrivenham F.C. and New College Swindon F.C. are members of the Hellenic Football League.

Swindon Town F.C. has an affiliated women's football team, Swindon Town W.F.C., who split from the 1967-founded Swindon Spitfires F.C. in 1993.

Rugby[]

Swindon St George are a rugby league team playing in the West of England Rugby League. The kit consists of black and red shirts with black shorts and socks. It was founded in 2007.

English Rugby player Jonny May lived in Chiseldon and attended The Ridgeway School & Sixth Form College located in Wroughton, both nearby villages to Swindon.

Ice hockey[]

The Swindon Wildcats play in the second-tier English Premier Ice Hockey League. Since their inception in 1986, the Wildcats have played their home games at the 2,800-capacity Link Centre in West Swindon.

Motor sports[]

Swindon Robins is a speedway team competing in the top national division, the SGB Premiership, where they were champions in the 2017 season. The team has operated at the Abbey Stadium, Blunsdon since 1949. There was a speedway track in the Gorse Hill area of Swindon in the early days of the sport in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Foxhill motocross circuit is 6 miles (9.7 km) southeast of the town and has staged Grand Prix events.

Musical roots[]

- Post-punk band XTC was formed in Swindon in 1972. Three of the band's singles reached the UK top 20, gaining them a cult following.[76]

- Electronic music group Meat Beat Manifesto was originally formed in 1987 in Swindon.[77]

- Justin Hayward from The Moody Blues was born and brought up in Swindon.[78]

Twin towns[]

Salzgitter, Germany

Salzgitter, Germany Ocotal, Nicaragua

Ocotal, Nicaragua Torun, Poland

Torun, Poland

See also[]

- Healthcare in Wiltshire

- List of people from Swindon

- List of twin towns in the United Kingdom

- Swindon Civic Trust

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Swindon BUA (E34004828)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Great Britain Historical GIS Project. "Swindon: Total Population". A Vision of Britain through time. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Swindon in the Domesday Book

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Wadard and Vital – 1066: The Hidden History in the Bayeux Tapestry". erenow.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John Chandler, Swindon Decoded, The Hobnob Press 2005, ISBN 0-946418-37-3.

- ^ ‘’Background’’ – The Mechanics Institution Trust, Swindon Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 23 July 2007. Reference updated 12 December 2013

- ^ 1850–1870 – The Mechanics Institution Trust, Swindon Archived 17 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 23 July 2007. Reference updated 12 December 2013

- ^ Background – The Mechanics Institution Trust, Swindon Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 23 July 2007. Reference updated 12 December 2013

- ^ This is Our Heritage — 1996 lecture by Swindon labour movement historian Trevor Cockbill Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 23 July 2007. Reference updated 12 December 2013

- ^ Background – The Mechanics Institution Trust, Swindon Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 July 2007. Reference updated 12 December 2013 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Swindon's Other Railway — the Swindon, Marlborough & Andover Railway Archived 19 June 2002 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 23 July 2007.

- ^ The Midland & South Western Junction Railway, Railspot Reloaded Archived 24 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.Retrieved on 23 July 2007.

- ^ GWR Museum picture gallery Archived 28 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 23 July 2007

- ^ Leonard Clark, Alfred Williams – His Life and Work, David and Charles 1969

- ^ Alfred Williams, Life in a railway factory, first published 1915, 2007 edition published by Sutton Publishing ISBN 978-0-7509-4660-5

- ^ Evening Star — Steam Locomotive Archived 3 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 29 November 2006. Retrieved on 21 July 2007.

- ^ The Electronic Age, swindonweb.com, 21 August 2014; retrieved 3 September 2019

- ^ "SwindonWeb – Brunel Tower David Murray John". swindonweb.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ The 20 best places to buy a property in Britain Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Times, Property pages, February 2008

- ^ More councils expected to ban speed cameras Archived 7 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Times, October 2008

- ^ [1] Archived 18 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Weaver, Matthew (23 October 2008). "More councils expected to ban speed cameras". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ New Swindon Archived 5 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 'County lines drugs gang recruits 40 pupils in one school-one for each class' report by Charles Hymas, Home Affairs Editor, The Daily Telegraph 23 August 2019 page 11.

- ^ "The Wiltshire (Borough of Thamesdown)(Structural Change) Order 1995". Opsi.gov.uk. 11 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ "Gallery: Conservatives hold council but Labour make gains". Swindon Advertiser. 6 May 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Humphreys, Chris (9 June 2017). "Town stays blue but it's tight in south". Swindon Advertiser. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ "Distance between Swindon, UK and Bristol, UK (UK)". distancecalculator.globefeed.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Distance between Swindon, UK and Reading, UK (UK)". distancecalculator.globefeed.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Crittall, Elizabeth; Rogers, Kenneth; Shrimpton, Colin (1983). "Geology". A history of Swindon to 1965. Wiltshire Library & Museum Service. ISBN 0-86080-107-1.

- ^ "1990 August maximum". Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "1971-00 Annual average warmest day". Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "1971-00 >25°C days". Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "1982 minimum". Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Climate Normals 1971–2000". MetOffice. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Climate Normals 1971–2000". KNMI. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Swindon population estimate by equality groups". Swindon Borough Council.

- ^ "Population Estimates and Projections". Swindon's Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. Swindon Borough Council. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Revealed: the fattest towns and cities in England". The Daily Telegraph. 4 February 2014. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ "South West England (United Kingdom): Counties and Unitary Districts & Settlements - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "City Population – Site Search". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Swindon (Unparished Area, United Kingdom) – Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018.

- ^ Angelini, Daniel (24 August 2018). "St Helena expats from 'Swindolena' to gather for sports day this weekend". Swindon Advertiser. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Community celebrates its golden anniversary, Swindon Advertiser, 31 May 2000 Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.Retrieved on 23 July 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Polish club closes doors for last time – Swindon Advertiser, 1 April 2007 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 24 July 2007

- ^ Born Abroad, BBC News Archived 17 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.Retrieved on 23 July 2007.

- ^ – Polish Community Focus Multicultural Matters Archived 11 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine.Retrieved on 23 July 2007

- ^ Modernising Services for Older People in Swindon– Avon & Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust, Swindon Primary Care Trust and Swindon Borough Council Archived 6 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.Retrieved on 24 July 2007.

- ^ Swindon Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine from British Listed Buildings, retrieved 9 January 2016

- ^ Swindon: Churches Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 9 from British History Online (London: Victoria County History, 1970), 144–159.

- ^ Places of Worship Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine from Total Swindon, retrieved 9 January 2016

- ^ "Swindon Honda Plant closes down with loss of 3,000 jobs". ITV News. 30 July 2021.

- ^ LTC Rolt, Isambard Kingdom Brumel, Penguin 1957.

- ^ "Swindon parish backs revised Stagecoach depot housing plans". This is Wiltshire. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps.

- ^ "GWR sets new Cardiff to London record". Swindon Advertiser. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Swindon Mela Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Family fun at Summer Breeze festival". Swindon Advertiser. 3 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Toploader to headline Swindon's Summer Breeze festival". Swindon Advertiser. 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Catch the Breeze". Swindon Advertiser. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ Craven, Richard (26 July 2007). "Swindon Shuffle 2007 – A Retrospective". BBC Wiltshire. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- ^ "Janice Thompson Performance Trust". www.jtptrust.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013.

- ^ "Swindon Designer Outlet - Factory Outlet in Swindon, West Oxfordshire - Oxfordshire Cotswolds". www.oxfordshirecotswolds.org. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "SPECIAL REPORT: Crossing success for Brunel Centre". Swindon Advertiser. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/wiltshire/8312009.stm BBC News

- ^ "'End of an era': Tented Market closes its doors". Swindon Advertiser. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ "Heart". Heart South West. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Greatest Hits Radio - Latest Show Schedule". Greatest Hits Radio. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Swindon 105.5 given Queens Award". media.info. 31 October 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Wiltshire - Listen Live - BBC Sounds". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Swindon Cable — Swindon View Point — The Local Channel, Swindoncable.co.uk Archived 9 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 21 July 2007.

- ^ "Swindon Campus – Oxford Brookes University". www.brookes.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Oxford Brookes opens its new campus in Swindon". Oxford Brookes University. 16 August 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Yilmaz, Tanya (3 February 2017). "New Oxford Brookes campus to officially open next week". Swindon Advertiser. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "BIG INTERVIEW: New Wyvern Theatre director Laura James". Swindon Advertiser. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "XTC biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Jack Dangers Of Meat Beat Manifesto Interviewed". The Quietus. 21 October 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Hutchinson, Charles (4 December 2014). "Justin Hayward, York Barbican, July 9". York Press. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

Further reading[]

- Swindon, Mark Child, Breedon Books, 2002, hardcover, 159 pages, ISBN 1-85983-322-5

- Francis Frith's Swindon Living Memories (Photographic Memories S.), Francis Frith and Brian Bridgeman, The Frith Book Company Ltd, 2003, Paperback, 96 pages, ISBN 1-85937-656-8

- An Awkward Size for a Town, Kenneth Hudson, 1967, David & Charles Publishers (ISBN none)

External links[]

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Swindon . |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swindon. |

- Official website

Swindon travel guide from Wikivoyage

Swindon travel guide from Wikivoyage- SwindonWeb

- Swindon

- Towns in Wiltshire

- Borough of Swindon

- Railway towns in England

- Polish communities