Ice Cube

Ice Cube | |

|---|---|

Ice Cube in January 2014 | |

| Born | O'Shea Jackson June 15, 1969 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Education | William Howard Taft Charter High School |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1986–present |

| Organization | Cube Vision |

| Television | Hip Hop Squares Barbershop |

| Spouse(s) | Kimberly Woodruff (m. 1992) |

| Children | 4, including O'Shea Jr. |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | icecube |

O'Shea Jackson Sr. (born June 15, 1969), known professionally as Ice Cube, is an American rapper, actor, and filmmaker. His lyrics on N.W.A's 1988 album Straight Outta Compton contributed to gangsta rap's widespread popularity,[1][2][3] and his political rap solo albums of 1990 (AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted) and 1991 (Death Certificate) were critically and commercially successful.[3][4][5][6] He has also had an active film career since the early 1990s.[7][8] He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of N.W.A in 2016.[9]

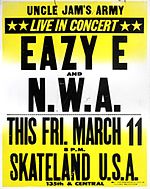

A native of Los Angeles, Jackson formed his first rap group called C.I.A. in 1986.[10] In 1987, with Eazy-E and Dr. Dre, he formed the pioneering gangsta rap group N.W.A.[10] As its lead rapper, he wrote some of Dre's and most of Eazy's lyrics on Straight Outta Compton,[1][3] a landmark album that shaped West Coast hip hop's early identity and helped differentiate it from East Coast rap.[2] N.W.A was also known for their violent lyrics, threatening to attack abusive police and innocent civilians alike,[11] which stirred controversy.[1][10] After a monetary dispute over the group's management by Eazy-E and Jerry Heller, Cube left N.W.A in late 1989, teaming with New York artists and launching a solo rap career.[10] His first two solo albums, AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted (1990) and Death Certificate (1991), were critically acclaimed.

Ice Cube entered cinema by playing Doughboy in director John Singleton's feature debut Boyz n the Hood, a 1991 drama named after a 1987 rap song[2] that Ice Cube wrote.[7] Ice Cube also cowrote and starred in the 1995 comedy film Friday; "coarse and ribald",[12] it premised a successful franchise and reshaped his persona into a friendly movie star.[8] His directorial debut was the 1998 film The Player's Club. By 2020, his acting roles included about 40 films, among them the 1999 war comedy Three Kings, family comedies like the Barbershop series, and buddy cop comedies 21 Jump Street, 22 Jump Street, and Ride Along.[12] He was an executive producer of many of these films, as well as of the 2015 biopic Straight Outta Compton.

Personal life and side ventures

Ice Cube was born on June 15, 1969, in Los Angeles, to Doris, a hospital clerk and custodian, and Hosea Jackson, a machinist and UCLA groundskeeper.[13][14][15][16] He has an older brother,[17] and they had a half-sister who was murdered when Cube was 12.[18][19] He grew up on Van Wick Street in the Westmont, California section of South Los Angeles.[20][21]

In ninth grade at George Washington Preparatory High School in Los Angeles,[22] Cube began writing raps once challenged by a friend nicknamed "Kiddo" to do so in typewriting class.[23] "Kiddo" lost.[23] Explaining his own stage name, Cube implicates his own older brother: "He threatened to slam me into a freezer and pull me out when I was an ice cube. I just started using that name, and it just caught on."[23][24][25]

Cube also attended William Howard Taft High School in Woodland Hills, California.[13] Soon after he wrote and recorded a few locally successful rap songs with N.W.A, he left for Arizona to enroll in the Phoenix Institute of Technology in the fall 1987 semester.[13][26] In 1988, with a diploma in architectural drafting, he returned to the Los Angeles area and rejoined N.W.A, but kept a career in architecture drafting as a backup plan.[13][27]

In 1990, he formed his own record label, Street Knowledge, whereby a musical associate via the rap group Public Enemy introduced him to the Nation of Islam (NOI).[28] Ice Cube converted to Islam.[29] Although denying membership in the NOI,[30] whose ideology often rebukes whites and especially Jews,[31] he readily adopted its ideology of black nationalism,[4] familiar to the rap community.[32] Still, he has claimed to heed his own conscience[28] as a "natural Muslim, 'cause it's just me and God".[33] Questioned in 2017, he said, in part, that he thinks "religion is stupid".[34] He estimated, "I'm gonna live a long life, and I might change religions three or four times before I die. I'm on the Islam tip—but I'm on the Christian tip, too. I'm on the Buddhist tip as well. Everyone has something to offer to the world."[34]

On April 26, 1992, Ice Cube married Kimberly Woodruff, born September 1970.[35][36] As of 2017, they have four children together.[37] In 2005, asked about the balance between his music and his parenting, Cube discussed counseling his children to appraise the violence depicted in all media, not just in music lyrics.[38] In the 2015 biopic Straight Outta Compton, his own son, O'Shea Jr., portrayed him.[39] In a 2016 interview, he offered his favorite movie as the 1975 film Jaws, and his favorite among his own songs as "It Was a Good Day".[40] Commercially, Cube has endorsed Coors Light beer and St. Ides malt liquor,[41] and licensed a clothing line, Solo by Cube. And in 2017, he launched Big3, a 3-on-3 basketball league starring former NBA players. Its first season started that June with eight teams, an eight-week regular season, playoffs, and a championship game.[42]

Musical career

In 1986 at age 16, Ice Cube began rapping in the trio C.I.A., but soon joined the newly formed rap group N.W.A. He was N.W.A's lead rapper and main ghostwriter on its official debut album, 1988's Straight Outta Compton. Via financial dispute, he left by the start of 1990. During 1990, his debut solo album, AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted, found him also leading a featured rap group, Da Lench Mob.[30]

Meanwhile, he helped develop the rapper Yo Yo.[3][43]

1986: C.I.A.

With friend Sir Jinx, Ice Cube formed the rap group C.I.A., and performed at parties hosted by Dr. Dre. Since 1984, Dre was a member of a popular DJ crew, the World Class Wreckin' Cru, which by 1985 was also performing and recording electro rap. Dre had Cube help write the Wreckin Cru's hit song "Cabbage Patch". Dre also joined Cube on a side project, a duo called Stereo Crew, which made a 12-inch record, "She's a Skag", released on Epic Records in 1986.[44]

In 1987, C.I.A. released the Dr. Dre-produced single "My Posse". Meanwhile, the Wreckin' Cru's home base was the Eve After Dark nightclub, about a quarter of a mile outside of the city Compton in Los Angeles county. While Dre was on the turntable, Ice Cube would rap, often parodying other artists' songs. In one instance, Cube's rendition was "My Penis", parodying Run-DMC's "My Adidas".[45] In 2015, the nightclub's co-owner and Wreckin' leader Alonzo Williams would recall feeling his reputation damaged by this and asking it not to be repeated.[46]

1986–1989: N.W.A.

At 16, Cube sold his first song to Eric Wright, soon dubbed Eazy-E, who was forming Ruthless Records and the musical team N.W.A, based in Compton, California.[13] Himself from South Central Los Angeles, Cube would be N.W.A's only core member not born in Compton.

Upon the success of the song "Boyz-n-the-Hood"—written by Cube, produced by Dre, and rapped by Eazy-E, helping establish gangsta rap in California—Eazy focused on developing N.W.A,[47] which soon gained MC Ren. Cube wrote some of Dre's and nearly all of Eazy's lyrics on N.W.A's official debut album, Straight Outta Compton, released in August 1988.[1] Yet by late 1989, Cube questioned his compensation and N.W.A's management by Jerry Heller.[48]

Cube also wrote most of Eazy-E's debut album Eazy-Duz-It. He received a total pay of $32,000, and the contract that Heller presented in 1989 did not confirm that he was officially an N.W.A member.[49] After leaving the group and its label in December, Cube sued Heller, and the lawsuit was later settled out of court.[49] In response, N.W.A members attacked Cube on the 1990 EP 100 Miles and Runnin', and on N.W.A's next and final album, Niggaz4Life, in 1991.[50]

1989–1993: Early solo career, AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted, Death Certificate, and The Predator

In early 1990, Ice Cube recorded his debut solo album, AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted, in New York with iconic rap group Public Enemy's production team, the Bomb Squad. Arriving in May 1990, it was an instant hit, further swelling rap's mainstream integration. Controversial nonetheless, it drew accusations of misogyny and racism. The album introduces Ice Cube's affirmation of black nationalism and ideology of black struggle.

Cube appointed Yo-Yo, a female rapper and guest on the album, to the head his record label, and helped produce her debut album Make Way for the Motherlode. Also in 1990, Cube followed up with an EP—Kill At Will—critically acclaimed, and rap's first EP certified Platinum.[51]

His second album Death Certificate was released in 1991.[52] The album thought to as more focused, yet even more controversial, triggering accusations of anti-white, antisemitic, and misogynist content. The album was split into two themes: the Death Side, "a vision of where we are today", and the Life Side, "a vision of where we need to go". The track "No Vaseline" scathingly retorts insults directed at him by N.W.A's 1990 EP and 1991 album, which call him a traitor.[50][53] But besides calling for hanging Eazy-E as a "house nigga", the track blames N.W.A's manager Jerry Heller for exploiting the group, mentions that he is a Jew, and calls for his murder.[54][55] Ice Cube contended that he mentioned Heller's ethnicity merely incidentally, not to premise attack, but as news media mention nonwhite assailants' races.[55] The track "Black Korea", also deemed racist,[52] was also thought as foreseeing the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[51] Broadening his audience, though, Cube toured with Lollapalooza in 1992.[30]

Cube's third album, The Predator, arrived in November 1992. Referring to the 1992 Los Angeles riots, the "Wicked" sing opens, "April 29 was power to the people, and we might just see a sequel." The Predator was the first album ever to debut at No. 1 on both the R&B/hip-hop and pop charts. Singles include "It Was a Good Day" and "Check Yo Self", songs having a "two-part" music video. Generally drawing critical praise, the album is his most successful commercially, over three million copies sold in the US. After this album, Cube's rap audience severely diminished, and never regained the prominence of his first three albums.[12]

During this time, Cube began to have numerous features on other artists' songs. In 1992, Cube assisted on Del the Funky Homosapien's debut album and on Da Lench Mob's debut album, which Cube produced, and featured on the Kool G Rap & DJ Polo song "Two to the Head." In 1993, he worked on Kam's debut album. Also in 1993, Cube and Ice-T collaborated on the track "Last Wordz" off 2Pac's album Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z..

1993–1998: Lethal Injection and forming Westside Connection

Cube's fourth album, Lethal Injection, came out in late 1993. Here, Cube borrowed from the then-popular G-funk popularized by Dr. Dre. Although not received well by critics, the album brought successful singles, including "Really Doe", "Bop Gun (One Nation)", "You Know How We Do It", and "What Can I Do?" After this album, Ice Cube effectively lost his rap audience.[12]

Following Lethal Injection, Cube focused on films and producing albums of other rappers, including Da Lench Mob, Mack 10, Mr. Short Khop, and Kausion.[3][51] In 1994, Cube teamed with onetime N.W.A groupmate Dr. Dre, who was then leading rap's G-funk subgenre, for the first time since Cube had left the group, and which had disbanded upon Dre's 1991 departure. The result was the Cube and Dre song "Natural Born Killaz", on the Murder Was The Case soundtrack, released by Dre's then-new label, Death Row Records.

In 1995, Cube joined Mack 10 and WC in forming a side trio, the Westside Connection. Feeling neglected by East Coast media, a longstanding issue in rap's bicoastal rivalry, the group aimed to reinforce West pride and resonate with the undervalued. The Westside Connection's first album, Bow Down (1996), featured tracks like "Bow Down" and "Gangstas Make the World Go 'Round" that reflected the group's objectives. The album was certified Platinum by year's end. Interpreting rapper Common's song "I Used to Love H.E.R." as a diss of West Coast rap, Cube and the Westside Connection briefly feuded with him, but they resolved amicably in 1997.[56]

It was also at this time that Cube began collaborating outside the rap genre. In 1997, he worked with David Bowie and Nine Inch Nails singer Trent Reznor on a remix of Bowie's "I'm Afraid of Americans". In 1998, Cube was featured on the band Korn's song "Children of the Korn", and joined them on their Family Values Tour 1998.

1998–2006: War & Peace Vol. 1 & 2 and Westside Connection reunion

In November 1998, Cube released his long-awaited fifth solo album War & Peace Vol. 1 (The War Disc). The delayed sixth album, Volume 2, arrived in 2000. These albums feature the Westside Connection and a reunion with his old N.W.A members Dr. Dre and MC Ren. Cube also received a return favor from Korn, as they appeared on his song "Fuck Dying" from Vol. 1. Many fans maintained that these two albums, especially the second, were lesser in quality to his earlier work.[57] In 2000, Cube also joined Dr. Dre, Eminem & Snoop Dogg for the Up in Smoke Tour.[58]

In 2002, Cube appeared on British DJ Paul Oakenfold's solo debut album, Bunkka, on the track "Get Em Up".

Released in 2003, Westside Connection's second album, Terrorist Threats, fared well critically, but saw lesser sales. "Gangsta Nation" (featuring Nate Dogg), the only single released, was a radio hit. After a rift between Cube and Mack 10 about Cube's film work minimizing the group's touring, the Westside Connection disbanded in 2005.

In 2004, Cube featured on the song "Real Nigga Roll Call" by Lil Jon & the East Side Boyz, the then leaders of rap's crunk subgenre.

2006–2012: Laugh Now, Cry Later, Raw Footage, and I Am the West

In 2006, Cube released his seventh solo album, Laugh Now, Cry Later, selling 144,000 units in the first week.[59] Lil Jon and Scott Storch produced the lead single, "Why We Thugs". In October, Ice Cube was honored at VH1's Annual Hip Hop Honors, and performed it and also the track "Go to Church". Cube soon toured globally in the Straight Outta Compton Tour—accompanied by rapper WC from the Westside Connection—playing in America, Europe, Australia, and Japan.

Amid Cube's many features and brief collaborations, September 2007 brought In the Movies, a compilation album of Ice Cube songs on soundtracks.[60]

Cube's eighth studio album, Raw Footage, arrived on August 19, 2008, yielding the singles "Gangsta Rap Made Me Do It" and "Do Ya Thang". Also in 2008, Cube helped on Tech N9ne's song "Blackboy", and was featured on The Game's song "State of Emergency".

As a fan of the NFL football team the Raiders, Cube released in October 2009 a tribute song, "Raider Nation".[61] In 2009, Ice Cube performed at the Gathering of the Juggalos, and returned to perform at the 2011 festival.[62]

On September 28, 2010, his ninth solo album, I Am the West, arrived with, Cube says, a direction different from any one of his other albums. Its producers include West Coast veterans like DJ Quik, Dr. Dre, E-A-Ski, and, after nearly 20 years, again Cube's onetime C.I.A groupmate Sir Jinx. Offering the single "I Rep That West", the album debuted at #22 on the Billboard 200 and sold 22,000 copies in its first week. Also in 2010, Cube signed up-and-coming recording artist named 7Tre The Ghost, deemed likely to be either skipped or given the cookie-cutter treatment by most record companies.[63]

In 2011, Cube featured on Daz Dillinger's song "Iz You Ready to Die" and on DJ Quik's song "Boogie Till You Conk Out".

In 2012, Ice Cube recorded a verse for a remix of the Insane Clown Posse song "Chris Benoit", from ICP's The Mighty Death Pop! album, appearing on the album Mike E. Clark's Extra Pop Emporium.[64]

In September 2012, during Pepsi's NFL Anthems campaign, Cube released his second Raiders anthem "Come and Get It".[65]

2012–present: Everythang's Corrupt and forming Mount Westmore

In November 2012, Cube released more details on his forthcoming, tenth studio album, Everythang's Corrupt. Releasing its title track near the 2012 elections, he added, "You know, this record is for the political heads."[66][67] But the album's release was delayed.[68] On February 10, 2014, iTunes brought another single from it, "Sic Them Youngins on 'Em",[69] and a music video followed the next day.[70] Despite a couple of more song releases, the album's release was delayed even beyond Cube's work on the 2015 film Straight Outta Compton. After a statement setting release to 2017,[71] the album finally arrived on December 7, 2018.[72]

In 2014, Cube appeared on MC Ren's remix "Rebel Music", their first collaboration since the N.W.A reunion in 2000.[73]

In 2020, Cube joined rappers Snoop Dogg, E-40, Too Short and formed the supergroup Mt. Westmore. The group's debut album is slated for release in April 2021.[74][75][76]

Film and television career

Since 1991, Ice Cube has acted in nearly 40 films, several of which are highly regarded.[12] Some of them, such as the 1992 thriller Trespass and the 1999 war comedy Three Kings, highlight action.[12] Yet most are comedies, including a few adult-oriented ones, like the Friday franchise, whereas most of these are family-friendly, like the Barbershop franchise.[12]

Narrative

John Singleton's seminal film Boyz n the Hood, released in July 1991, debuted the actor Ice Cube playing Doughboy, a persona that Cube played convincingly.[7] Later, Cube starred with Ice-T and Bill Paxton in Walter Hill's 1992 thriller film Trespass, and in Charles Burnett's 1995 film The Glass Shield. Meanwhile, Cube declined to costar with Janet Jackson in Singleton's 1993 romance Poetic Justice, a role that Tupac Shakur then played.

Cube starred as the university student Fudge in Singleton's 1995 film Higher Learning.[77] Singleton, encouraging Cube, had reportedly told him, "If you can write a record, you can write a movie."[78] Cube cowrote the screenplay for the 1995 comedy Friday, based on adult themes, and starred in it with comedian Chris Tucker. Made with $3.5 million, Friday drew $28 million worldwide. Two sequels, Next Friday and Friday After Next, arrived in 2000 and 2002.

In 1997, playing a South African exiled to America who returns 15 years later, Cube starred in the action thriller Dangerous Ground, and had a supporting role in Anaconda. In 1998, writing again, the director Ice Cube debuted in The Players Club. In 1999, he starred alongside George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg as a staff sergeant in Three Kings, set in the immediate aftermath of the Gulf War, whereby the United States attacked Iraq in 1990, an "intelligent" war comedy critically acclaimed.[12] In 2002, Cube starred in Kevin Bray's All About the Benjamins, and in Tim Story's comedy film Barbershop.

In 2004, Cube played in Barbershop 2 and Torque. The next year, he replaced Vin Diesel in the second installment of the XXX film series and also appeared in the family comedy Are We There Yet?, which premised his role in its 2007 sequel Are We Done Yet?. In 2012, Cube appeared in 21 Jump Street. He also appeared in its sequel, 22 Jump Street, in 2014. That year, and then to return in 2016, he played alongside comedian Kevin Hart in two more Tim Story films, Ride Along and Ride Along 2. Also in 2016, Cube returned for the third entry in the Barbershop series. And in 2017, Cube starred with Charlie Day in the comedy Fist Fight.

Documentary

In late 2005, Ice Cube and R. J. Cutler co-created the six-part documentary series Black. White., carried by cable network FX.

Ice Cube and basketball star LeBron James paired up to pitch a one-hour special to ABC based on James's life.[79]

On May 11, 2010, ESPN aired Cube's directed documentary Straight Outta L.A., examining the interplay of Los Angeles sociopolitics, hip hop, and the Raiders during the 1980s into the 1990s.[80][81]

Serial television

Ice Cube's Are We There Yet? series premiered on TBS on June 2, 2010. It revolves around a family adjusting to the matriarch's new husband, played by Terry Crews. On August 16, the show was renewed for 90 more episodes,[82] amounting to six seasons. Cube also credits Tyler Perry for his entrée to TBS.[83] In front of the television cameras, rather, Cube appeared with Elmo as a 2014 guest on the PBS children's show Sesame Street.[84]

Controversies

In 2020, he was accused of a "long, disturbing history of anti-Semitism".[55] This traces to his 1991 song "No Vaseline",[55][85] which calls N.W.A's members slurs of blacks and calls N.W.A's manager Jerry Heller a "white man", "white boy", "Jew", "devil", "white Jew", and "cracker".[54][86] In 2015, Ice Cube expressed regret at including the word Jew, as the attacks are on Heller, not "the whole Jewish race".[54] That same year, he was sued for—but has denied—ordering a rabbi's assault.[55][85] And in June 2020, some of Ice Cube's Twitter posts—promoting NOI leader Louis Farrakhan,[32] an allegedly antisemitic mural,[87] and associated conspiracy theories[88]—triggered wide accusations of antisemitism.[89] Suggesting himself "just pro-Black", not "anti anybody", Cube dismissed "the hype", and professed "telling my truth".[90]

Discography

- Studio albums

- AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted (1990)

- Death Certificate (1991)

- The Predator (1992)

- Lethal Injection (1993)

- War & Peace Vol. 1 (The War Disc) (1998)

- War & Peace Vol. 2 (The Peace Disc) (2000)

- Laugh Now, Cry Later (2006)

- Raw Footage (2008)

- I Am the West (2010)

- Everythang's Corrupt (2018)

Filmography

Films

| Year | Film | Functioned as | Role | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Director | Producer | Screenwriter | Actor | |||

| 1991 | Boyz n the Hood | Darin "Doughboy" Baker | ||||

| 1992 | Trespass | Savon | ||||

| 1993 | CB4 | Himself (cameo) | ||||

| 1994 | The Glass Shield | Teddy Woods | ||||

| 1995 | Higher Learning | Fudge | ||||

| Friday | Craig Jones | |||||

| 1997 | Dangerous Ground | Vusi Madlazi | ||||

| Anaconda | Danny Rich | |||||

| 1998 | The Players Club | Reggie | ||||

| I Got the Hook Up | Gun runner | |||||

| 1999 | Three Kings | Sgt. Chief Elgin | ||||

| Thicker Than Water | Slink | |||||

| 2000 | Next Friday | Craig Jones | ||||

| 2001 | Ghosts of Mars | James 'Desolation' Williams | ||||

| 2002 | All About The Benjamins | Bucum | ||||

| Barbershop | Calvin Palmer | |||||

| Friday After Next | Craig Jones | |||||

| 2004 | Torque | Trey Wallace | ||||

| The N-Word | Himself | |||||

| Barbershop 2: Back in Business | Calvin Palmer | |||||

| 2005 | Are We There Yet? | Nick Persons | ||||

| Beauty Shop | ||||||

| Sierra Leone's Refugee All Stars | ||||||

| XXX: State of the Union | Darius Stone / XXX | |||||

| 2007 | Are We Done Yet? | Nick Persons | ||||

| 2008 | First Sunday | Durell Washington | ||||

| The Longshots | Curtis Plummer | |||||

| 2009 | Janky Promoters | Russell Redds | ||||

| 2010 | Lottery Ticket | Jerome "Thump" Washington | ||||

| 2011 | Rampart | Kyle Timkins | ||||

| 2012 | 21 Jump Street | Capt. Dickson | ||||

| 2014 | Ride Along | Detective James Payton | ||||

| 22 Jump Street | Capt. Dickson | |||||

| The Book of Life | The Candle Maker (voice role) | |||||

| 2015 | Straight Outta Compton | |||||

| 2016 | Ride Along 2 | Detective James Payton | ||||

| Barbershop: The Next Cut | Calvin Palmer | |||||

| 2017 | XXX: Return of Xander Cage | Darius Stone / XXX | ||||

| Fist Fight | Strickland | |||||

| 2020 | The High Note | Jack Robertson | ||||

| TBA | Flint Strong | Jason Crutchfield | ||||

| TBA | Last Friday | Craig Jones | ||||

Television

| Year | Film | Functioned as | Role | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer | Screenwriter | Director | Actor | ||||

| 1994 | The Sinbad Show | Himself | Episode: The Mr. Science Show | ||||

| 2002 | The Bernie Mac Show | Himself | Episode: Goodbye Dolly | ||||

| 2005 | BarberShop: The Series | ||||||

| WrestleMania 21 | Himself | ||||||

| 2006 | Black. White. | ||||||

| 2007 | Friday: The Animated Series | ||||||

| 2010 | 30 for 30 | Episode: Straight Outta L.A. | |||||

| 2010–2013 | Are We There Yet? | Terrence Kingston | Recurring Role; 20 Episodes | ||||

| 2014 | The Rebels | Pilot of unproduced series | |||||

| 2017 | The Defiant Ones | Himself | Documentary | ||||

Video games

| Title | Year | Role | Other notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Call of Duty: Black Ops | 2010 | Chief Petty Officer Joseph Bowman/SOG multiplayer announcer | Voice and likeness actor | [91][92] |

Awards and nominations

Film awards

Ice Cube has received nominations for several films in the past. To date, he has won two awards:

- 2000: Blockbuster Entertainment Award: Favorite Action Team (for Three Kings)

- 2002: MECCA Movie Award: Acting Award

Music awards

- VH1 Hip Hop Honors 2006

- 2006 Honoree Snoop Dogg

- BET Hip-Hop Awards 2009

- BET Honores 2014

Other

- Hollywood Walk of Fame star 2017[93]

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Steve Huey, "N.W.A: Straight Outta Compton", AllMusic.com, Netaktion LLC, visited 14 Jun 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Loren Kajikawa, "Compton via New York", Sounding Race in Rap Songs (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), pp 91–93.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Todd Boyd, Am I Black Enough for You?: Popular Culture from the 'Hood and Beyond (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1997), p 75 skims Ice Cube's early successes in music, while indexing "Ice Cube" reveals analysis of his political rap.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lakeyta M. Bonnette, Pulse of the People: Political Rap Music and Black Politics (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), p 71.

- ^ Allen Gordon, "Ice Cube: Death Certificate (Street Knowledge/Priority, 1991)", in Oliver Wang, ed., Classic Material: The Hip-hop Album Guide (Toronto: ECW Press, 2003), p 87.

- ^ Preezy Brown, "18 socio-political lyrics from Ice Cube's 'Death Certificate' that still resonate in 2016", Vibe.com, Prometheus Global Media, LLC., 1 Nov 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gail Hilson Woldu, The Words and Music of Ice Cube (Westport, CT & London, UK: Praeger Publishers, 2008), pp 44–45.

- ^ Jump up to: a b David J. Leonard, "Ice Cube", in Mickey Hess, ed., Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007), p 311.

- ^ "N.W.A | Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". www.rockhall.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Steven Otfinoski, "Ice Cube", African Americans in the Performing Arts (New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2003), p 108.

- ^ The album's first three tracks—"Straight Outta Compton", "Fuck tha Police", and "Gangsta Gangsta"—are the classic N.W.A declarations.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Pete Cashmore, "Frozen in time: Why does nobody want to hear Ice Cube rap any more?", TheGuardian.com, Guardian News & Media Limited, 30 Nov 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Jessie Carney Smith (2006). Encyclopedia of African American Business, Volume 1. Greenwood.

- ^ Muhammad, Baiyina W. (2006). "O'Shea 'Ice Cube' Jackson (1965– ), Rapper, Lyricst, Producer, Actor, ScreenWriter, Director, Film Producer and Businessman". In Jessie Carney Smith (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American Business. 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 403–5. ISBN 9780313331107.

- ^ "Ice Cube". Hiphop.sh. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (November 15, 2002). "They call him Mister Cube". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Mark Armstrong (August 13, 2014). "The Believer Interview: Ice Cube : Longreads Blog". Blog.longreads.com. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ Ice Cube – Actor/Musician | Teen Interview. Teen nick. Retrieved on December 31, 2011.

- ^ Cube also has a cousin, Teren Delvon Jones, who is the rapper Del tha Funky Homosapien, member of the rap group Hieroglyphics, who also worked with Gorillaz. Another cousin is Kam of rap group The Warzone.

- ^ Kennedy, Gerrick D. (2017). Parental Discretion Iz Advised: The Rise of N.W.A and the Dawn of Gangsta Rap.

- ^ Coleman, Brian (October 13, 2014). "The Making of Ice Cube's "AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted"". Cuepoint. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- ^ "Actor and Musician Ice Cube: 'Are We There Yet?'". NPR. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Ice Cube Goes Undercover on Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, and Wikipedia | GQ". YouTube. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Ice Cube Explains His Moniker And Gives One To Stephen, interview on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert (aired June 20, 2017, published to YouTube on June 21, 2017)

- ^ Ice Cube's Google Autocomplete Interview (Wired.com, published to YouTube on April 11, 2016)

- ^ Jefferson, Jevaillier (February 2004). "Ice Cube: Building On His Vision". Black Collegian. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ "Ice Cube Celebrates the Eames". Dezeen. December 8, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Martin Cizmar, "Ice Cube is one of rap's original gangsters, but he is also one of hip hop's most unconventional political activists", Willamette Week, 23 Aug 2016, updated 3 Oct 2016.

- ^ "These 9 famous Americans are all Muslim". Business Insider. October 27, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Chillin' with Cube". The Guardian. February 25, 2000.

- ^ The Southern Poverty Law Center, an advocacy group, is categorical in its declaration that the Nation of Islam is a hate group "Nation of Islam", SPLCenter.org, The Southern Poverty Law Center, visited 15 Jun 2020]. Yet although that view has arguments in its favor, including the NOI's ideology of black superiority and white guilt as well as Jewish guilt, that is not a consensus view among scholars, who identify other context and functions of the NOI [Phyllis B. Gerstenfeld, Hate Crimes: Causes, Controls, and Controversies, 4th ed.] (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2018), indexing "Nation of Islam".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dawn-Marie Gibson, "Embracing the Nation: Hip-hop, Louis Farrakhan, and alternative music", in Andre E. Johnson, ed., Urban God Talk: Constructing a Hip Hop Spirituality (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2013), pp 140–141.

- ^ "Muslim Celebrities". CBS. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stern, Marlow (February 2, 2017). "Ice Cube on Donald 'Easy D' Trump: 'Everybody is getting what they deserve'". The Daily Beast. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Kimberly Woodruff". Ecelebrityfacts.com. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ "23 Yrs & Counting: Ice Cube Gives Advice On The Key to Marital Bliss".

- ^ "Ice Cube". IMDb. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Gross, Terry (January 10, 2005). "Actor and Musician Ice Cube: 'Are We There Yet?'". Fresh Air. NPR.

- ^ "Ice Cube's Son O'Shea Jackson Jr. Had to Audition for Straight Outta Compton". August 7, 2015.

- ^ "Ice Cube Answers The Web's Most Searched Questions". Wired. April 11, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Schultz, E.J. "Ice Cube on Coors Light, Burger King and Gay Marriage". AdAge.com. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ "Ice Cube creates BIG3". AdAge.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Simon Glickman, "Yo Yo", Contemporary Musicians, Encyclopedia.com, Cengage, updated 5 May 2020.

- ^ Johson, Bill (May 31, 2010). "Ice Cube Reminisces On His Very First Gig And Single". The Urban Daily. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ Brown, Jake (2006). Dr. Dre in the Studio: From Compton, Death Row, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, 50 Cent, the Game, and Mad Money: the Life, Times, and Aftermath of the Notorious Record Producer, Dr. Dre. London: Amber Books Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 9780976773559.

- ^ World Class Wreckin' Cru Founder Alonzo Williams Addresses Dr. Dre Gay Rumors & 'Straight Outta Compton', Allhiphop.com, August 24, 2015

- ^ Loren Kajikawa, Sounding Race in Rap Songs (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), p 93.

- ^ Ice Cube: Attitude (McIver, 2002) ISBN 1-86074-428-1

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ice Cube: Attitude, Joel McIver, p.70, Foruli Classics, 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sacha Jenkins, Elliott Wilson, Jeff Mao, Gabe Alvarez & Brent Rollins, "Mo' beef, mo' problems: #7, N.W.A vs. Ice Cube", Ego Trip's Book of Rap Lists (New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1999), p 238.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2007). "Ice Cube – Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jeffries, David (October 31, 1991). "Death Certificate – Ice Cube". AllMusic. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ^ Vlad Lyubovny, interviewer, "DJ Yella: All of NWA knew Ice Cube won with 'No Vaseline' ", VladTV–DJVlad @ YouTube "Verified" channel, 22 Aug 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Soren Baker, The History of Gangster Rap: From Schoolly D to Kendrick Lamar, the Rise of a Great American Art Form (New York: Abrams Image, 2018), indexing "Vaseline Eazy house nigga Heller Jew" reveals brief discussion of "No Vaseline", specifically its treatment of its two main targets, N.W.A's leader Eazy-E and N.W.A's manager Jerry Heller, whom Ice Cube depicts as teaming to financially molest N.W.A's other members.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Marlow Stern, "Ice Cube's long, disturbing history of anti-Semitism", TheDailyBeast.com, The Daily Beast Company LLC, 11 Jun 2020.

- ^ "Ice Cube says beef with Common was a 'dark moment' in his career". BET. February 3, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Birchmeier, Jason. ""War & Peace, Vol. 2 (The Peace Disc)" – Overview". Allmusic. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (July 17, 2000). "Four Hours of Swagger from Dr. Dre and Friends". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ "Ice Cube – Billboard Albums". Allmusic. 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ Jeffries, David. "In the Movies" – Overview. AllMusic. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ^ "Raider Nation!". Ice Cube. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ 2011 Gathering Of The Juggalos Infomercial on YouTube

- ^ Jacobs, Allen (March 19, 2010). "Ice Cube Blogs About "I Am The West", Mack 10 | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales". HipHop DX. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ "Grapevine: ICP, Ice Cube team up on new album | The Detroit News". detroitnews.com. May 17, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Lilah, Rose. "Ice Cube – Come And Get It [New Song]". HotNewHipHop. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Ortiz, Edwin (November 1, 2012). "Ice Cube Details New Song "Everythang's Corrupt" & Album, Praises Kendrick Lamar | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales". HipHop DX. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "iTunes – Music – Everythang's Corrupt – Single by Ice Cube". Itunes.apple.com. January 4, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Twitter / icecube". Twitter. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "iTunes – Music – Sic Them Youngins On 'Em – Single by Ice Cube". Itunes.apple.com. February 11, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "Ice Cube – Sic Them Youngins On 'Em | Stream & Listen [New Song]". Hotnewhiphop.com. February 11, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Parisi, Paula (October 6, 2016). "Ice Cube Goes 'Real Old-School' for 'Mafia III' Original Song 'Nobody Wants to Die'". Billboard. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ "Ice Cube on hip-hop beefs, new album, upcoming film 'Excessive Force'". rollingout.com. October 5, 2018. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Tardio, Andres. MC Ren Announces Ice Cube Reunion, Disses This Era Of Rap Archived November 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, HipHopDX, May 30, 2014.

- ^ "Too Short and E-40 confirm new joint album with Snoop Dogg and Ice Cube". www.revolt.tv.

- ^ "Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, Too Short and E-40 form supergroup Mt. Westmore". NME. March 17, 2021.

- ^ "Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, Too $hort & E-40 Post Mt. Westmore Graphic On Instagram As Debut Date Approaches". HipHopDX. March 20, 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (January 11, 1995). "Film review: Higher Learning; short course in racism on a college campus". The New York Times.

- ^ "Ice Cube—brief article". Jet. February 28, 2000. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ James Pitches ABC on TV Drama Based on His Life USA Today, December 20, 2008

- ^ "Blog Archive " Ice Cube: "Raiders fans were gangster's way before we came into the picture"". Sports Radio Interviews. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "ESPN 30 for 30". ESPN. June 17, 1994. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ 'Are We There Yet' Renewed by TBS for 90 More Episodes August 16, 2010 – tvbythenumbers

- ^ "Ice Cube's Life Story?! Talks Tyler Perry, Woody Harrelson, TV Success and More!". UrbLife.com. August 16, 2010.

- ^ "Elmo and Ice Cube are Astounded". October 28, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b JTA, "Rapper Ice Cube scuffles with rabbi outside casino, hit with $2ml lawsuit", The Jerusalem Post, JPost.com, Jpost Inc., 30 May 2015.

- ^ "Ice Cube—'No Vaseline' lyrics", MetroLyrics.com, CBS Interactive Inc., 2020.

- ^ Jpost staff, "Simon Wiesenthal Center slams Ice Cube's antisemitic tweets", JerusalemPost.com, Jpost Inc., 11 Jun 2020, reports, in part, "The original 2012 mural titled Freedom for Humanity was created by Kalen Ockerman, better known as Mear One, and depicts Lord Rothschild and Paul Warburg sitting with other well-known people, such as English occultist Aleister Crowley, as they profit from the misery of other humans. The artist claimed his work stands for oppressed people, but many slammed it for focusing on Jewish figures." Showing an image of this mural, Ice Cube captioned, "Fuck the new normal until they fix the old normal!" [Twitter, @icecube, 6 Jun 2020].

- ^ Gil Kaufman, "Ice Cube criticized for posting string of anti-semitic images and conspiracy theories", Billboard.com, Prometheus Global Media, LLC, 11 Jun 2020.

- ^ Joseph A. Wulfsohn, "Ice Cube accused of sharing anti-Semitic images on Twitter", Fox News website, Fox News Network, LLC.,11 Jun 2020.

- ^ Aaron Bandler, "Ice Cube responds to accusations of anti-semitism: 'I've been telling my truth'", Jewish Journal website, Tribe Media Corp, 12 Jun 2020, reports and directs to a June 10 tweet by Ice Cube saying, in full, "What if I was just pro-Black. This is the truth brother. I didn't lie on anyone. I didn't say I was anti anybody. DONT BELIEVE THE HYPE. I've been telling my truth".

- ^ "Ice Cube's Voice in Black Ops". N4G. October 29, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (October 28, 2010). "Ice Cube Adding Call Of Duty To His Resume". Kotaku. Gizmodo Media Group. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (June 13, 2017). "Ice Cube Says 'You Don't Get Here By Yourself' at Hollywood Walk of Fame Ceremony". Billboard. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ice Cube. |

- Official website

- Ice Cube at AllMusic

- Ice Cube at IMDb

- Ice Cube

- 1969 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American rappers

- 20th-century American singers

- 20th-century Muslims

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American rappers

- 21st-century American singers

- 21st-century Muslims

- African-American film directors

- African-American film producers

- African-American male actors

- African-American male rappers

- African-American Muslims

- African-American screenwriters

- African-American television producers

- American draughtsmen

- American film producers

- American male film actors

- American male rappers

- American male screenwriters

- American male television actors

- American male video game actors

- American male voice actors

- American music industry executives

- American music video directors

- Big3 people

- Capitol Records artists

- Converts to Islam

- EMI Records artists

- Film directors from Los Angeles

- Film producers from California

- Gangsta rappers

- Interscope Records artists

- Male actors from California

- Male actors from Los Angeles

- N.W.A members

- People from Baldwin Hills, Los Angeles

- Priority Records artists

- Rappers from California

- Rappers from Los Angeles

- Ruthless Records artists

- Screenwriters from California

- Television producers from California

- West Coast hip hop musicians

- Westside Connection members

- William Howard Taft Charter High School alumni