Boyz n the Hood

| Boyz n the Hood | |

|---|---|

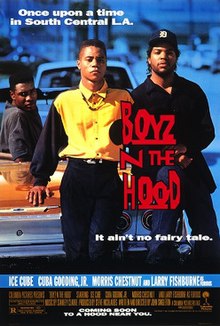

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Singleton |

| Written by | John Singleton |

| Produced by | Steve Nicolaides |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charles Mills |

| Edited by | Bruce Cannon |

| Music by | Stanley Clarke |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $57.5 million (North America)[1] |

Boyz n the Hood is a 1991 American coming-of-age hood drama film written and directed by John Singleton in his feature directorial debut.[2] It stars Ice Cube, Cuba Gooding Jr., Morris Chestnut, Laurence Fishburne, Nia Long, Regina King, and Angela Bassett. Boyz n the Hood follows Tre Styles (Gooding Jr.), who is sent to live with his father Furious Styles (Fishburne) in South Central Los Angeles, surrounded by the neighborhood's booming gang culture. The film's title is a double entendre; a play on the term boyhood and a reference to the 1987 N.W.A rap song of the same name, written by Ice Cube.

Singleton initially developed the film as a requirement for application to film school in 1986 and sold the script to Columbia Pictures upon graduation in 1990. During writing, he drew inspiration from his own life and from the lives of people he knew and insisted he direct the project. Principal photography began in September 1990 and was filmed on location from October to November 1990. The film is notable for featuring breakout roles for Ice Cube, Cuba Gooding Jr., Morris Chestnut, and Nia Long.

Boyz n the Hood premiered in Los Angeles on July 2, 1991, and was theatrically released in the United States ten days later. The film became a critical and commercial success, praised for its emotional weight, acting, and writing. It grossed $57.5 million in North America, and was nominated for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay at the 64th Academy Awards, making Singleton the youngest person and the first African-American to be nominated for Best Director.

The film was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival.[3] In 2002, the United States Library of Congress deemed it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[4][5]

Plot[]

1984[]

Ten-year-old Tre Styles lives with his mother Reva, in Inglewood, near Los Angeles International Airport. After Tre gets into an altercation at school, his teacher informs Reva that, even though he is highly intelligent, he has a volatile temper and lacks respect for authority. Concerned about Tre's future, Reva sends him to live in Crenshaw with his father, Jason "Furious" Styles, from whom she hopes Tre will learn valuable life lessons and to be able to mature, but assures him he will be permitted to return to her one day.

Tre soon reunites with his friends, Darrin "Doughboy" Baker, Doughboy's maternal half-brother Ricky, and Chris, their mutual friend. Furious immediately has Tre rake the leaves off the front lawn, informing him of work and responsibility. Chris sneers at Furious' offer to pay them for raking the leaves, implying he makes more participating in criminal activity. That night, a burglar enters the house and Tre hears his father shooting as he flees. They wait for the police, and two officers arrive an hour later; the white officer is civil and professional, while the black officer is hostile and displays a contempt of other black men.

The next day, Tre, Ricky, Doughboy, and Chris venture to a nearby neighborhood where Chris knows the location of a dead human body. While the quartet is there, a group of adolescents loitering and drinking on a sidewalk confront them about the discovery of the body. One of the adolescents tricks Ricky into throwing him his football. Doughboy is disgusted with his brother and tells him he'll never get the ball back. Doughboy tries to retrieve it anyway but is beaten and kicked by the ball thief. While the older boys walk away, one of them gives Ricky his ball back. Later in the day, Furious goes fishing with Tre, telling him of his military experience in the Vietnam War. He advises Tre to never join the Army, arguing that a black man has no place in the Army. When Tre and Furious return home, they see Doughboy and Chris being arrested for shoplifting with Brenda, Ricky and Doughboy's mother, looking on from her front porch.

1991[]

Seven years later at a BBQ party, Doughboy, now a Crips[6] gang member, is celebrating his recent release from jail, along with his friends, including Chris, who is now paralyzed and uses a wheelchair as a result of a gunshot wound, and new friends and fellow Crip members Dooky and Monster. Ricky, now a star running back for Crenshaw High School, lives with Brenda, his girlfriend Shanice, and their infant son. Tre has grown into a mature and responsible teenager, works at a clothing shop at the Fox Hills Mall, and aspires to attend college with his girlfriend, Brandi. Their relationship is strained over Tre's desire to have sex, while Brandi, a devout Catholic, wishes to wait until after marriage.

Ricky hopes to win a scholarship from the University of Southern California. During a visit from a recruiter, Ricky learns that he must score at least a 700 on the SATs in order to qualify. Tre and Ricky both take the test together, and they visit Furious at work. Furious takes them to Compton to talk about the dangers of decreasing property values in the black community.

That night, during a local street racing gathering, Ricky has a confrontation with Ferris, a high-ranking Bloods member. This soon escalates into an argument which causes Doughboy to brandish his gun, warding off the Bloods. Moments later, Ferris fires his own gun into the air, causing everyone to panic and flee. Tre leaves with Ricky and states his desire to leave Los Angeles, but they are soon pulled over by the police. The officer turns out to be the same one who responded to the burglary call made by Furious seven years back, and he intimidates and threatens Tre. Tre visits Brandi's house and breaks down; after she consoles him, they have sex for the first time.

The next day, Doughboy and Ricky get into a fight. While Tre and Ricky walk to a nearby store, they see Ferris and the Bloods driving around the neighborhood, and in an attempt to avoid them, the two cut through the back alleys and split up. As Tre turns his back to Ricky, Ferris' car cuts off Ricky's path, and one of Ferris' men shoots Ricky in the leg and back with a shotgun, killing him instantly.

Doughboy, Dooky, Monster and Chris rush over to the scene but catch up with Tre too late. Devastated, the five boys carry Ricky's dead body back home. When Brenda and Shanice see Ricky's corpse, they tearfully break down and blame Doughboy, who unsuccessfully tries to comfort them and explain himself. That night, a distraught Brenda reads Ricky's SAT results, discovering he scored a 710, more than enough to qualify for the scholarship.

The remaining boys vow vengeance on Ricky's assailants; Furious finds Tre preparing to take his gun, but convinces Tre to abandon his plans for revenge. Shortly after, Tre sneaks out to join Doughboy, Dooky and Monster. That night, as the four search for Ricky's killers, Tre asks to be let out of Doughboy's car and returns home. When Tre arrives at home, Furious confronts him, and the two depart to their bedrooms silently with no words exchanged.

Meanwhile, Doughboy, Dooky and Monster continue to search for the three assailants and they eventually find them eating at a fast food restaurant and prepare a drive-by shooting. The Bloods spot the car and attempt to flee, but Monster manages to shoot all three of them, killing one, and wounding Ricky's killer and Ferris. Doughboy exits the car, shoots Ricky's killer, and confronts Ferris. Ferris denies "pulling the trigger" and insults Doughboy, who promptly executes him in response.

The next morning, Doughboy visits Tre and understands his reasons for exiting the car. Doughboy knows that he will eventually face retaliation for the murder he committed the previous evening and accepts the consequences of his crime-ridden lifestyle. He plaintively questions why America does not care about the plight of those in the ghetto, and sorrowfully notes he has no family left after Ricky's death and Brenda's disowning of him. Tre embraces him and tells Doughboy he still has one brother left.

The epilogue reveals that Ricky was buried the next day, and that Doughboy was murdered two weeks later. Tre and Brandi later go on to attend Morehouse and Spelman colleges in Atlanta, respectively.

Cast[]

- Cuba Gooding Jr. as Jason 'Tre' Styles III

- Desi Arnez Hines II as Tre age 10

- Angela Bassett as Reva Devereaux

- Laurence Fishburne as Jason 'Furious' Styles Jr.

- Ice Cube as Darren 'Doughboy' Baker

- Baha Jackson as Doughboy age 10

- Morris Chestnut as Ricky Baker

- Donovan McCrary as Ricky age 10

- Nia Long as Brandi

- Nicole Brown as Brandi age 10

- Tyra Ferrell as Brenda Baker

- Redge Green as Chris 'Little Chris'

- Kenneth A. Brown as Chris age 10

- Whitman Mayo as The Old Man

- John Singleton as The Mailman

- Dedrick D. Gobert as 'Dooky'

- Baldwin C. Sykes as 'Monster'

- Tracey Lewis-Sinclair as Shaniqua

- Alysia Rogers as Shanice

- Regina King as Shalika

- Lexie Bigham as 'Mad Dog'

- Raymond Turner as Ferris

- Lloyd Avery II as Ferris' Triggerman (Knucklehead #2)

- Jessie Lawrence Ferguson as Officer Coffey[7]

Production[]

Singleton wrote the film based on his own life and that of people he knew.[8] When applying for film school, one of the questions on the application form was to describe "three ideas for films". One of the ideas Singleton composed was titled Summer of 84, which later evolved into Boyz n the Hood.[8] During writing, Singleton was influenced by the 1986 film Stand by Me, which inspired both an early scene where four young boys take a trip to see a dead body and the closing fade-out of main character Doughboy.[8]

Upon completion, Singleton was protective of his script, insisting that he be the one to direct the project, later explaining at a retrospective screening of the film "I wasn't going to have somebody from Idaho or Encino direct this movie."[2] He sold the script to Columbia Pictures in 1990, who greenlit the film immediately out of interest in making a film similar to the comedy-drama film Do the Right Thing (1989).

The role of Doughboy was specifically written for Ice Cube, whom Singleton met while working as an intern at The Arsenio Hall Show.[8] Singleton also noted the studio was unaware of Ice Cube's standing as a member of rap group N.W.A.[8] Singleton claims Gooding and Chestnut were cast because they were the first ones who showed up to auditions,[8] while Fishburne was cast after Singleton met him on the set of Pee-wee's Playhouse, where Singleton worked as a production assistant and security guard.[9]

Long grew up in the area the film depicts and has said, “It was important as a young actor to me that this feels real because I knew what it was like go home from school and hear gunshots at night.” Bassett referred to the filmmaker as her “little brother” on set. “I'd been in LA for about three years and I was trying, trying, trying to do films,” she said. “We talked, I auditioned and he gave me a shot. I’ve been waiting to work with him ever since.”[2]

The film was shot in sequence, with Singleton later noting that, as the film goes on, the camera work gets better as Singleton was finding his foothold as a director.[2] He has a cameo in the film, appearing as a postman handing over mail to Brenda as Doughboy and Ricky are having a scuffle in the front yard.

Reception and legacy[]

Critical response[]

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 94% based on 70 reviews and an average score of 8.4/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Well-acted and thematically rich, Boyz N the Hood observes urban America with far more depth and compassion than many of the like-minded films its success inspired."[10] At Metacritic, the film received an average score of 76 out of 100 based on 20 reviews, which indicates "generally favorable reviews".[11]

Cultural impact[]

Boyz n the Hood kickstarted the acting careers of Gooding, Chestnut, and Long, who were relatively unknown before it. It also launched Ice Cube's career as a Hollywood actor and was Angela Bassett's and Regina King's first significant film role.[2]

The film has been referenced many times in other works, including works by Lupe Fiasco, Game, and Ice Cube himself. In 1994, British jungle DJ duo Remarc and Lewi produced a song titled "Ricky". The song itself is built up of various sound bites from the movie, particularly the scene where Ricky is murdered. Ice Cube also references the film in the song "Check Yo Self", stating "I make dough but don't call me Dough Boy / This ain't no fucking motion picture". In the 2008 movie Be Kind Rewind, there is a small reference to the scene where Ricky is shot.

On the July 12, 2011, episode of her self-titled talk show, Mo'Nique celebrated the 20th anniversary of the release of Boyz n the Hood with the director John Singleton, Cuba Gooding Jr., Yo-Yo, and Regina King. American rapper Vince Staples references the scene where Ricky gets shot in the back in the song "Norf Norf", informing the listener of the film's impact on his upbringing.

In 2016, 21 Savage referenced Ricky's murder in the song "No Heart", stating "21 Savage not Boyz N The Hood but I pull up on you / Shoot yo' ass in the back". He also referenced Ricky's murder in the song "Slidin", stating "He was talking crazy, he got blick / Savage keep a token, John Wick / Shoot him in the back like he Rick (Ricky) / Playing freeze tag, n***** it (Sticky)".

In popular culture[]

Australian alternative rock band TISM released a live VHS called Boyz n the Hoods in 1992, whose cover artwork is presented as a parody of the film's original VHS box, albeit with a fake disclaimer printed on the cover stating that due to a manufacturing error, the non-existent film was replaced with TISM's concert.

Characters and scenes from Boyz n the Hood are parodied in the 1996 American crime comedy parody film, Don't Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood.

In the 2015 American comedy film Get Hard, Kevin Hart's character is asked to talk about the reason for his fabricated incarceration years earlier. Fumbling for a story, he describes the final scene of Boyz n the Hood, passing it off as his own experience to Will Ferrell's character.

Awards and accolades[]

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Director | John Singleton | Nominated |

| Best Original Screenplay | Nominated | ||

| BMI Awards | Stanley Clarke | Won | |

| NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Motion Picture | Won | |

| MTV Movie Awards | Movie of the Year | Nominated | |

| Best New Filmmaker | John Singleton | Won | |

| New York Film Critics Circle | Best New Director | Won | |

| Political Film Society | For Peace | Won | |

| For Exposé | Nominated | ||

| For Human Rights | Nominated | ||

| Writers Guild of America | Best Original Screenplay | John Singleton | Nominated |

| Young Artist Award[12] | Outstanding Young Ensemble Cast in a Motion Picture | Won |

In 2007, Boyz n the Hood was selected as one of the 50 Films To See in your lifetime by Channel 4.

American Film Institute Lists

Soundtrack[]

| Year | Album | Peak chart positions | Certifications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | U.S. R&B | |||

| 1991 | Boyz n the Hood

|

12 | 1 | |

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Boyz N the Hood". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Smith, Nigel M (June 13, 2016). "John Singleton reflects on Boyz N the Hood: 'I didn't know anything'". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ "Boyz n the Hood". Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". National Film Preservation Board. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ Dalton, Andrew (April 30, 2019). "John Singleton found a perfect marriage of movie and moment". Associated Press. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "'Boyz n the Hood' Dirty Cop Actor Jessie Lawrence Ferguson Dead at 76". TMZ. April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Jones, Will (November 1, 2016). "Talking 'Boyz N the Hood' with Its Director John Singleton". Vice UK. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ "John Singleton Interview Part 1 of 3 - TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation. 24 September 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Boyz n the Hood (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Boyz n the Hood Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ^ "Thirteenth Annual Youth in Film Awards: 1990–1991". Young Artist Awards. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ "RIAA Gold & Platinum Searchable Database - Tony! Toni! Tone![permanent dead link]". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Boyz n the Hood |

- Boyz n the Hood at IMDb

- Boyz n the Hood at the TCM Movie Database

- Boyz n the Hood at AllMovie

- Boyz n the Hood at Box Office Mojo

- Boyz n the Hood at Rotten Tomatoes

- Boyz n the Hood at Metacritic

- Boyz in the Hood essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages [1]

- 1991 films

- English-language films

- 1991 crime drama films

- 1991 directorial debut films

- 1991 romantic drama films

- 1990s coming-of-age drama films

- 1990s gang films

- 1990s hip hop films

- 1990s teen drama films

- American films

- American coming-of-age drama films

- American crime drama films

- American gang films

- American romantic drama films

- American teen drama films

- American teen romance films

- African-American films

- Bloods

- Columbia Pictures films

- Coming-of-age romance films

- Crips

- Films about death

- Films about families

- Films about racism

- Films about revenge

- Films directed by John Singleton

- Films scored by Stanley Clarke

- Films set in 1984

- Films set in 1991

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films with screenplays by John Singleton

- Hood films

- United States National Film Registry films