Crenshaw, Los Angeles

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

Crenshaw | |

|---|---|

Neighborhoods of Los Angeles | |

| Nickname(s): The 'Shaw[1] | |

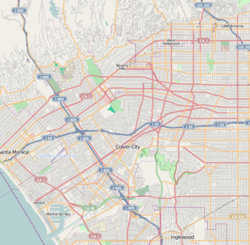

Crenshaw Location within Los Angeles | |

| Coordinates: 34°01′05″N 118°20′26″W / 34.01810°N 118.34064°WCoordinates: 34°01′05″N 118°20′26″W / 34.01810°N 118.34064°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| City | |

| Time zone | Pacific |

| ZIP Code | 90008 |

| Area Code | 323 |

Crenshaw, or the Crenshaw District, is a neighborhood in South Los Angeles, California.[2][3]

In the post–World War II era, a Japanese American community was established in Crenshaw. African Americans started migrating to the district in the mid 1960s, and by the early 1970s were the majority.[4]

The Crenshaw Boulevard commercial corridor has had many different cultural backgrounds throughout the years,[5] but it is still "the heart of African American commerce in Los Angeles".[6]

Geography[]

According to Google Maps,[7] the Crenshaw neighborhood is centered on Crenshaw Boulevard and Buckingham Road. The neighborhood of Baldwin Hills is to the south, Baldwin Village is to the west, and Leimert Park is to the east.

Cartographer Eric Brightwell considers Baldwin Village to be part of Crenshaw.[8] Google Maps includes in Crenshaw areas labelled by Brightwell as being Baldwin Hill Estates, Baldwin Hill, Baldwin Village, and southern parts of West Adams and Jefferson Park. Google Maps plots Crenshaw as bounded by Crenshaw Boulevard, Stocker Street, and South La Brea Avenue, with the border going along West Jefferson Boulevard to Vineyard Ave, northeast to West 30th Street, east to 11th Avenue, south and west along West Exposition Boulevard.[9][a]

Demographics[]

In the post-World War II era, a Japanese-American community was established in Crenshaw. There was an area Japanese school called Dai-Ichi Gakuen. Due to a shared sense of being discriminated against, many of the Japanese-Americans had close relationships with the African-American community.[10]

At its peak, it was one of the largest Japanese-American settlements in California, with about 8,000 residents around 1970, and Dai-Ichi Gakuen had a peak of 700 students.[10]

Beginning in the 1970s the Japanese American community began decreasing in size and Japanese-American businesses began leaving. Scott Shibya Brown stated that "some say" the effect was a "belated response" to the 1965 Watts riots and that "several residents say a wave of anti-Japanese-American sentiment began cropping up in the area, prompting further departures."[10] Eighty-two-year-old Jimmy Jike was quoted in the Los Angeles Times in 1993, stating that it was mainly because the residents' children, after attending universities, moved away.[10] By 1980, there were 4,000 Japanese ethnic residents, half of the previous size.[10] By 1990 there were 2,500 Japanese-Americans, mostly older residents. By 1993, the community was diminishing in size, with older Japanese Americans staying but with younger ones moving away.[10] That year, Dai-Ichi Gakuen had 15 students. Recently there has been a shift in a new generation of Japanese Americans moving back into the neighborhood.[10]

Government[]

Emergency service[]

The Los Angeles Police Department is responsible for law enforcement in the area. The Southwest Community police station is at 1546 W. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

The Los Angeles Fire Department operates one main fire station, Station 94 - in the area.

Post office[]

The United States Postal Service operates the Crenshaw Post Office, the Julian Dixon Post Office and the North Torrance Post Office.[11]

Education[]

Public schools are operated by the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD).

Schools[]

- Crenshaw High School, which is south of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and east of Crenshaw Boulevard, is the local public high school.

- Susan Miller Dorsey High School

The district's charter schools in the area include the KIPP network. KIPP Academy of Opportunity[12]

- Celerity Nascent Charter School[13]

- the New Design Charter School (built in 2004)

- View Park Preparatory High School

- View Park Preparatory Middle School.

Neighborhood[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

Crenshaw is a largely residential neighborhood of single-story houses, bungalows and low-rise condominiums and apartments. There are also commercial buildings with an industrial corridor along Jefferson Boulevard. There are also several other commercial districts throughout the neighborhood.

After courts ruled segregation covenants to be unconstitutional, the area opened up to other races. A large Japanese American settlement ensued, which can still be found along Coliseum Street, east and west of Crenshaw Boulevard.[10] African Americans started migrating to the district in the mid 1960s, and by the early 1970s later were the majority.[4]

In the 1970s, Crenshaw, Leimert Park and neighboring areas together had formed one of the largest African-American communities in the western United States. Crenshaw had suffered significant damage from both the 1992 Los Angeles riots and the 1994 Northridge earthquake but was able to rebound in the late 2000s with the help of redevelopment and gentrification.[14]

In 2006, the population of Crenshaw was around 27,600. Currently, there is a huge demographic shift increase in which many middle and lower-class blacks and Latinos are migrating to cities in the Inland Empire as well as cities in the Antelope Valley sections of Southern California as a form of gentrification.[15] The gentrification process continues into 2010's as the Crenshaw mall been approved for a major renovation plan, that will include apartments, shops, and more restaurants.[16]

Transportation[]

The K Line, known as the Crenshaw/LAX Line during planning and construction, is an 8.5-mile (13.7 km) light rail line that will "add eight new stations serving the Crenshaw neighborhood, Leimert Park, Inglewood, Westchester and surrounding areas".[17]

The line will run between the Expo/Crenshaw station and Aviation/96 Street station, transiting generally north-south along Crenshaw Boulevard.[18][19]

Notable places[]

- Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza shopping mall is a landmark. It was home to a tri-level Wal-Mart (formerly a Broadway department store, then later a JJ Newberry's), Sears and Macy's. Additional retail stores later were purchased by the mall such as Victoria's Secret, Forever 21, and Ashley Stewart, as well as office supply stores such as Staples.

- Marlton Square, (formerly known as Santa Barbara Plaza), was a shopping center. The center had aged over the years and was a failed redevelopment project.[20] Local city business developers and Kaiser Permanente purchased the land and demolished the old retail stores in 2011. A new Kaiser Permanente medical office building was built on the site.[citation needed]

- The Crenshaw Square Shopping Centre and sign, a local landmark, had been in some disrepair throughout the years. In 2007, the sign was replaced by a modern illuminated red-and-green sign. The Crenshaw Square outdoor shopping center was sold in 2015 and underwent a significant renovation in 2016.

- The West Angeles Church of God in Christ, a Pentecostal church near the intersection of Crenshaw and Exposition boulevards, is home to Bishop Charles E. Blake.

Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments[]

- Village Green is a neighborhood near Baldwin Hills. It is Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #174.

- The Holiday Bowl was a bowling alley and café known for being a center of ethnic diversity during the 1960s and 1970s. It featured a sushi bar known as the Sakiba Lounge with live musical acts. Its historic Modernist Googie architecture style has been refurbished by the buildings new tenants, Starbucks and Walgreens, along with a newly outdoor shopping center that opened in early 2006. It is City of Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument #688.[21][22]

Media[]

Motion picture[]

John Singleton's 1991 film Boyz n the Hood is a story set in Crenshaw. It was filmed in the Crenshaw neighborhood and other South Central (as it was called then; now called South Los Angeles) Los Angeles locations. It was Singleton's directorial debut and received Oscar nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay at the 64th Academy Awards.

Literature[]

The novel Southland, by Nina Revoyr, is set in the Crenshaw neighborhood.[23]

Television[]

The CW show All American is half-set in Crenshaw, as it is the main character's hometown.

Special events[]

- The annual Kingdom Day Parade: Celebrating Martin Luther King Jr., the Parade held its 35th edition in 2018. It is usually broadcast in the LA area on KABC-TV.[24] The parade goes west on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard to Crenshaw Boulevard.

- The Taste of Soul Festival takes place every October (since 2005).[25]

Notable people[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

- Tom Bradley, former mayor of Los Angeles[26]

- Darwin Cook, National Basketball Association

- Spencer Paysinger, National Football League

- Baron Davis, National Basketball Association

- Eric Davis, Major League Baseball

- Richard Elfman and Danny Elfman, musicians

- Tremaine Fowlkes, National Basketball Association

- James Hahn, former mayor of Los Angeles

- Kenneth Hahn, (1920–1997) Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors

- Nipsey Hussle, (1985-2019) rapper, entrepreneur, community activist[27][28][29]

- Ice-T, musician and actor

- DeSean Jackson, National Football League[30]

- Dom Kennedy, rapper

- Kurupt, rapper

- Arthur Lee, singer

- Lords of Lyrics, rap group

- Skee-Lo, rapper

- Darryl Strawberry, Major League Baseball

- Syd, singer and producer

- De'Anthony Thomas, National Football League

- Pam Ward, novelist

- David Fulcher, National Football League

- Tiffany Haddish, Comedian and Actress

- Ice Cube, Rapper

See also[]

- List of districts and neighborhoods of Los Angeles

- Crenshaw Boulevard

Notes[]

- ^ Where other reliable sources are available for the boundaries of neighborhoods, they should be treated preferentially to Google Maps and Google Street View. It is difficult if not impossible to verify as they are subject to change and documentation and archives are not available.

References[]

- ^ "Japanese and Blacks, Sharing the 'Shaw", News and Notes, NPR News, August 11, 2005

- ^ https://bass.house.gov/our-district/district-map-ca-37-overview

- ^ http://www.lapdonline.org/southwest_community_police_station

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kurashige, Scott (January 30, 2014). "Growing Up Japanese American in Crenshaw and Leimert Park". Communities. KCET. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Meares, Hadley (May 17, 2019). "How Crenshaw became black LA's main street". Curbed LA. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Robinson-Jacobs, Karen (May 2, 2001). "Noticing a Latin Flavor in Crenshaw". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Brightwell map

- ^ "Google Maps search for "Crenshaw, Los Angeles"". Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Brown, Scott Shibuya (October 3, 1993). "Crenshaw: Littler Tokyo : Although their children have grown and gone, older Japanese-Americans still evince pride, loyalty in their changing community". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "USPS.com® - Location Details". Tools.usps.com. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to KIPP Academy of Opportunity". kippkao.org. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ "Celerity Schools". celerityschools.org. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ Easter, Makeda (January 30, 2019). "Destination Crenshaw art project aims to reclaim the neighborhood for black L.A." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Mu'min, Nijla (September 20, 2015). "Calm before the storm of gentrification". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ^ Barragan, Bianca (June 18, 2018) "Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza redevelopment wins City Council approval" Curbed LA

- ^ "Temporary art banners installed at construction sites along Crenshaw/LAX corridor". Thesource.metro.net. May 12, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Sumers, Brian (January 21, 2014). "Metro breaks ground on new $2 billion L.A. Crenshaw/LAX Line". Daily Breeze. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ "Crenshaw Corridor Specific Plan" (PDF). City of Los Angeles. April 19, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "Urban renewal project in L.A. begets blight instead - By Ted Rohrlich, Los Angeles Times Staff Writer 10:38 PM PDT, 27 April 2008". latimes.com. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ "Game Over For Holiday Bowl?". November 21, 2008. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "Monument Search Results Page". Cityplanning.lacity.org. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "Fiction Book Review: SOUTHLAND by Nina Revoyr, Author, Dennis Cooper, Editor . Akashic $15.95 (348p) ISBN 978-1-888451-41-2". Publishersweekly.com. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "Dr Martin Luther King Jr. celebrated at Kingdom Day Parade". abc7.com. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Flores, Jessica (October 22, 2019). "As South LA changes, Destination Crenshaw is 'absolutely necessary'". Curbed LA. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Axelrod, Jeremiah B. C. (Occidental College). "The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles." The Journal of American History, 12/2008. p. 909-910. Cited: p. 910.

- ^ Zorka, Zoe (April 2, 2019). "Remembering the Business of Nipsey Hussle: From Entertainer to Entrepreneur". The Source. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Blay, Zeba (April 4, 2019). "Nipsey Hussle's Work In The Black Community Went Deeper Than You Think". HuffPost. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Jennings, Angel. "Nipsey Hussle had a vision for South L.A. It all started with a trip to Eritrea". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Tafur, Vic (May 21, 2011). "NFL star DeSean Jackson talks bullying in Oakland". SFGate. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crenshaw, Los Angeles. |

- Crenshaw, Los Angeles

- Neighborhoods in Los Angeles

- African-American history in Los Angeles

- Japanese-American culture in Los Angeles

- 1904 establishments in California

- South Los Angeles