Internal anal sphincter

| Internal anal sphincter | |

|---|---|

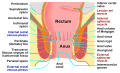

Coronal section through the anal canal. B. Cavity of urinary bladder V.D. Vas deferens. S.V. Seminal vesicle. R. Second part of rectum. A.C. Anal canal. L.A. Levator ani. I.S. Internal anal sphincter. E.S. External anal sphincter. | |

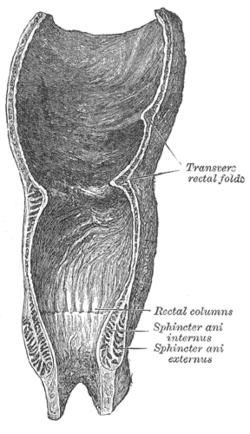

Coronal section of rectum and anal canal | |

| Details | |

| Nerve | Pelvic splanchnic nerves (S4), thoracicolumbar outflow of the spinal cord |

| Actions | Keeps the anal canal and orifice closed, aids in the expulsion of the feces |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus sphincter ani internus |

| TA98 | A05.7.05.011 |

| TA2 | 3018 |

| FMA | 15710 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The internal anal sphincter, IAS, (or sphincter ani internus) is a ring of smooth muscle that surrounds about 2.5–4.0 cm of the anal canal; its inferior border is in contact with, but quite separate from, the external anal sphincter. It is myogenic in nature and playing phasic and tonic state for relaxation and contraction. This myogenic tone is based on Ca2+/Calmodulin/MLCK/RhoA/ROCK signaling cascade pathway.[1] Recent studies suggested, BDNF is the member of the neurotrophin family; having next target for basal IAS and NANC relaxation.[2]

It is about 5 mm thick, and is formed by an aggregation of the involuntary circular fibers of the rectum. Its lower border is about 6 mm from the orifice of the anus.

Actions[]

Its action is entirely involuntary, and it is in a state of continuous maximal contraction. It helps the Sphincter ani externus to occlude the anal aperture and aids in the expulsion of the feces. Sympathetic fibers from the superior rectal and hypogastric plexuses stimulate and maintain internal anal sphincter contraction. Its contraction is inhibited by parasympathetic fiber stimulation. This sphincter is tonically contracted most of the time to prevent leakage of fluid or gas, but is relaxed upon distention of the rectal ampulla, requiring voluntary contraction of the puborectalis and external anal sphincter.[3] The internal anal sphincter is not innervated by the pudendal nerve, which carries somatic (motor and sensory) fibers that provide the innervation to the external anal sphincter.[4]

Role in continence[]

The IAS contributes 55% of the resting pressure of the anal canal. It is very important for bowel continence, especially for liquid and gas. When the rectum fills beyond a certain capacity, the rectal walls are distended, triggering the defecation cycle. This begins with the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, RAIR, where the IAS relaxes. This is thought to allow a small amount of rectal contents to descend into the anal canal where specialized mucosa samples whether it is gas, liquid or solid. Problems with the IAS often present as degrees of fecal incontinence (especially partial incontinence to liquid) or mucous rectal discharge.[5]

Regenerative medicine[]

In 2011 it was announced by the Wake Forest School of Medicine that the first bioengineered, functional anal sphincters had been constructed in a laboratory made from muscle and nerve cells, providing a solution for anal incontinence.[6][7]

Additional images[]

Intestines

Anatomy of the human anus

See also[]

References[]

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 426 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 426 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Rattan, Satish (1 January 2017). "Ca2+/calmodulin/MLCK pathway initiates, and RhoA/ROCK maintains, the internal anal sphincter smooth muscle tone". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 312 (1): G63–G66. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00370.2016. ISSN 1522-1547. PMC 5283903. PMID 27932502.

- ^ Singh, Arjun; Mohanty, Ipsita; Singh, Jagmohan; Rattan, Satish (1 January 2020). "BDNF augments rat internal anal sphincter smooth muscle tone via RhoA/ROCK signaling and nonadrenergic noncholinergic relaxation via increased NO release". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 318 (1): G23–G33. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00247.2019. ISSN 1522-1547. PMC 6985850. PMID 31682160.

- ^ Moore, K., Dalley, A., Agur, A. "Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 6th Edition.

- ^ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~humananatomy/part_6/chapter_36.html

- ^ David E. Beck, Patricia L. Roberts, Theodore J. Saclarides, Anthony J. Senagore, Michael J. Stamos, Steven D. Wexner (Editors) (2007). The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-24846-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Human cells engineered to make functional anal sphincters in lab", Science Daily. August 10, 2011. Retrieved 3 feb 2017

- ^ "Anal Sphincters", Wake Forest School of Medicine. December 12, 2015. Retrieved 3 feb 2017

External links[]

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Perineum

- Anus