Irvine Harbour

This article uses bare URLs, which may be threatened by link rot. (May 2021) |

| Irvine Harbour | |

|---|---|

Irvine Harbour | |

| Location | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Location | Irvine |

| Coordinates | 55°36′29″N 4°41′06″W / 55.6080°N 4.6850°W |

| Details | |

| Opened | 17th century |

| Owned by | NPL Estates |

| Type of harbor | Pleasure Craft |

| Harbour master | Arran Cameron |

| Statistics | |

| Website [1] | |

The harbours serving Irvine at Seagatefoot and Fullarton in North Ayrshire have had a long and complex history. Irvine's harbour was one of the most important ports in Scotland in the 16th century. Across from the main harbour at Fullarton on the River Irvine there was also terminal for the ICI-Nobel Explosives plant on the River Garnock. Much of the harbour went into decline in the 19th century when Glasgow, Greenock and Port Glasgow achieved higher prominence as sea ports. There was still some commercial sea traffic linked to local needs, though the harbour went into further terminal decline in the 20th century. The weir on the River Irvine forms the formal upper limit of the harbour.[1]

Formerly owned by ICI, Irvine Harbour is now the property of NPL Estates who also own the Big Idea site, the Bridge of Scottish Invention, locally known as the 'Sliding bridge', and other land on the Ardeer peninsular.[2] Irvine Harbour is now officially closed as a commercial port. Until recently NPL provided a slipway for dinghys, as well as moorings and berths for pleasure craft. However, silting has taken place and the Scottish Maritime Museum's berths are not for public use.

History[]

The Roman port of 'Vindogara Sinus' has been associated with Irvine, however no authenticated Roman remains have been found to confirm or support this and the few Roman coins found are not sufficient to decide the issue either way. A Roman Camp site near Irvine was tentatively identified in 1760 and a site at Marressfoot has been suggested for the Roman port.[3]

Etymology[]

The name 'Irvine' may be of Celtic language origin, meaning 'green river' in as in the Welsh river named Irfon. The name has many recorded variants, such as Ervin (1259); Irwyn (1322); Irewin (1429–30); Irrvin (1528); and Irwin (1537).[4] Another source also lists Yrewin (1140); Irvin (1230); Orewin (1295), with a suggested meaning of 'west flowing river.'[5]

Seagatefoot Harbour[]

The medieval harbour at Irvine was at Seagatefoot near the old Seagate Castle.[6] In 1184 records a castle of 'Hirun' is recorded which has been taken as referring to Irvine.[7] The original wooden castle tower was built some time before 1184, rebuilt in stone in the 1360s and then remodelled and expanded by Hugh the 3rd Earl of Eglinton in around 1565. Seagate Castle overlooked and controlled the Seagate, Irvine's oldest street, once the main route between the town and the old harbour at Seagatefoot, which by 1606 was useless due to silting and had been abandoned.

The castle of Irvine, built to control the harbour and town, lay within the lordship of Cunninghame, which had been granted by David I to Hugh de Morville, Lord High Constable of Scotland. In 1196 the lordship passed from the de Morville family, through failure of male heirs, and then descended through various families, among whom were the Balliols. Robert the Bruce granted the lordship to Robert the Steward who became King Robert II of Scotland.[8]

In circa 1566[9] it is recorded that in riches and commodiousness of sey port ... nocht mekle inferior to Air. In 1634 Sir William Brereton visited Irvine and his host, Mr James Blare (Blair) told him that more that ten thousand people had emigrated through Irvine to Ireland (forty sailing hours away) in circa 1632-1633, mainly from around Aberdeen and Inverness. He described Irvine as Daintily situate, both upon a navigable arm of the sea, and in a dainty, pleasant, level, champaign country. The port at that time traded with Dublin and wines were imported from France.[10] In the 1650s it is however described as a pretty small port but at present clogged and choked up with sand, which the western sea beats into it, so as it wrestles for life to maintain a small trade with France, Norway and Ireland with herring and other goods, brought on horseback from Glasgow for the purchasing of timber, wine, etc.[11]

King James IV employed a French gardener to create a new garden at Stirling Castle and paid him 28 shillings in 1501 to collect vines from Irvine Harbour and to have them delivered safely to the castle.[12]

Fullarton Harbour[]

In 1665 a totally new harbour for Irvine was begun at Fullarton, flanking the estuary on its left bank some distance from Seagatefoot, provided with a masonry quay, some of the stones having been pulled out of the river bed.[6] By 1723 Irvine was described as a tolerable seaport with upon the key, a good face of business especially the coal trade to Dublin. Trade exceeded that of Ayr harbour, however even smaller ships could be stuck in the harbour for months.[11] by 1793 the harbour was well established, with storehouses, coal-sheds, etc.[6]

Irvine's harbour at Fullarton functioned as the chief port for Glasgow until the early 18th century when Port Glasgow developed, then a century later the River Clyde was deepened to take ships directly to Glasgow. Exports from Fullarton included coal, tar, lime, and chemicals, whilst imports included hemp, iron, wood from Finland and Russia, soda ash from Belgium and a special sand for the Portland Glass Factory.[13] Industries included shipbuilding, engineering, foundries, sawmills and chemicals.

Fullarton was originally a village lying outwith the Royal Burgh of Irvine, latterly it became a burgh in its own right in the Parish of Dundonald until the Irvine Burgh Act of 1881 expanded Irvine's boundaries to engulf it.

As stated, from the late 17th century coal exports from local pits became an important export and by 1793 over 24,000 tons were shipped out annually with 51 vessels engaged in the trade. It is recorded that at first the coals `were carried away in small boats and when these arrived in port, a large horn fixed to a post at the quay by an iron chain was blown, summoning the 'colliers' who loaded their small horses and brought the coal to the harbour, most of it going to Ireland and by 1839 the total annual figure had risen to 44,000 tons.[6]

The two short canals at the Misk Pit were connected to the estuary via lock gates and special lighters were built that were loaded directly into their holds and then they made their way down to the harbour where they were unloaded into larger vessels.[14]

The Ballast Bank, known as 'Wee Ireland' was formed from sand unloaded from empty ships that had been loaded with it as ballast.[15] Alex McKinlay, harbourmaster in the 1860s, built his house named 'Emerald Bank' next to where the tide once flowed across the road into and out of the Sluices Loch, of a significant size, which lay between the main road and the Gottries. The house name commemorates that the Sluices, drained 1839-42, was filled up with sand-ballast from Ireland. The ships discharging the ballast would have taken away cargoes of coal.

Two dredgers were required to prevent the harbour silting up and these were named the 'Irvine' and the 'Stanley.' A depth of sixteen to seventeen feet in the main channel was required. The Irvine Bar, that is prone to shifting, was always the greatest difficulty and some ships had to be partly unloaded to give them a draft that allowed them to pass over it,[13] with a depth of 13 ft [4m] at high spring tides. Dredging ceased in the 1960s when Nobel stopped importing raw materials and Irvine became a 'tidal harbour'.[13]

In 1976 there were three rail-mounted cranes at the quay, two had been built by Alexander Chaplin & Co, Glasgow, and one by Smith Rodley.[6] A considerable number of railway freight sidings at one time ran down to the harbour quays and the nearby chemical works in the time of the Glasgow and South Western Railway and later the London, Midland and Scottish railway. The harbour is no longer connected with the national rail network.

In 1832 a plan of Irvine shows the presence of a shipbuilding yard, and features such as the small lochan known as 'The Sluices', lime kiln, lime mill, a single pier, and a flagstaff.[16] Rubble jetties ran seaward either side of the harbour entrance running into Irvine Bay.

The Ship Inn is the oldest Public house in Irvine, built in 1596 and has held a drinks licence as an inn since 1754. The former Harbour Master's Office is a single storeyed early 19th-century cottage, currently (2012) classified as 'at risk', which may have begun life as a farmhouse[17] or a fisherman's dwelling.

The 'Preen Hull' was a sand-hill near the Irvine Bar from which many toilet-pins were recovered over the years, as well as an elegant pewter brooch and a number of other articles made of brass or iron. 'Preen' is Scots for a metal pin.[18]

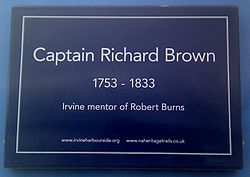

In 2013 the Irvine Burns Club and partners established an 'Irvine Harbourside Heritage Trail' honouring eleven significant individuals closely associated with the harbour. Richard Brown was one of those honoured with a plaque in recognition of his influence upon Robert Burns.

The Nobel Harbour[]

The main shipping in the 20th century was light coastal traffic and vessels destined for the Nobel Explosives facility. This facility had its own quay, which, although disused since the 1990s, is still visible from Irvine Harbour. This quay was connected by rail with the rest of the works and had its own travelling crane.

In 1870 Nobel Industries Limited had been founded by Alfred Nobel for the manufacture of the dynamite. Ardeer was chosen for the company's first factory because of its isolation and desolation. Blasting gelatine, gelignite, ballistite, guncotton, and cordite were also produced here. At its peak, the factory was employing nearly 13,000 men and women. The firm merged in 1926 with Brunner, Mond & Company, the United Alkali Company, and the British Dyestuffs Corporation, forming Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), then one of Britain's largest firms. Nobel Industries continued as the ICI Nobel division of the company, however in 2002 Nobel Enterprises was sold to Inabata.

Smuggling[]

After being unroofed in around 1746, Seagate Castle ceased to be inhabited by Montgomerie family retainers. However, far from being abandoned, the Castle became the haunt of smugglers, thieves and beggars. After nightfall, the locals shunned it, and, if any property was stolen in the town, it was the first place to be searched. In the 1800s, people still living could remember seeing the smugglers' "wee still" sitting in the large kitchen fireplace producing illicit spirits.[8] Whisky from Arran was illegally imported as was grain from Ireland.[6]

Shipbuilding[]

Old maps show up to two shipyards and the last one to survive, the Ayrshire Dockyard Company, remained active until after World War II, although its last ship, the S.S. Alfonso, was built just before WW2. The shipyard's main business after this was the refitting ships and also the manufacture of fittings for other ships, such as the Cunard liner Queen Elizabeth 2. It is now home to part of the Scottish Maritime Museum with a wide variety of vessels on display, including the 'Spartan', one of the last surviving Clyde puffers.[19]

Fishing[]

Several boats worked from the harbour within living memory, the catch mainly being herring that was sent by train to Glasgow.[20] Line fishing catches included whiting, cod, mackerel, haddock, and flounder. Some of the lines had up to two hundred hooks, each baited with mussels.[20]

Irvine lifeboat[]

The first Irvine lifeboat was housed next to the Harbour or Shoremaster's Office where the oddly angled building can still be seen. The boat sat on a four wheeled waggon and was pushed down on to the beach to be launched into the harbour opposite Garnock Foot.

The Port of Irvine had a lifeboat station from 1864, rescues being carried out by volunteer seamen. The first Royal National Lifeboat Institution boat at Irvine was the 'Pringle Kidd', given by Miss Kidd of Lasswade. From 1874-87 the lifeboat was the 'Isabella Frew', followed by the 'Busbie' in 1887. A number of heroic rescues were carried out by the crews of these lifeboats.[21] The 'Jane Anne' of 1898 was the fifth and last Irvine lifeboat, taking part in seven rescues and saving twelve lives; she is now preserved in the Scottish Maritime Museum.[22]

Irvine no longer has a lifeboat station; in 1908 the OS maps shows the lifeboat station situated near the landward end of the breakwater and the slip running down to the harbour entrance, marked at this position on OS maps until the 1958 edition. The supports of the lifeboat slipway are still discernable at low tide. The lifeboat station closed in 1914 after which the Troon station took over its responsibilities, although the lifeboat house building survived for many more years as a shop in 1927 with cubicles for swimmers at the rear, then as a base for the Sea Scouts and Sea Cadets in the 1940s, until demolition in the 1960s.[23]

Boyd's Automatic tide signalling apparatus[]

A manual system of indicating the depth of the entry into the harbour existed in the 1830s, Tom Tennant was the operator, based at a signal station on the top of sand hills. Tom hoisted balls to indicate the depth of water on the bar, and also acted as ferryman across the river.

Irvine Harbour is home to a unique and distinctive category 'B' structure which displayed the tide level to ships entering the harbour until the 1970s. It was opened in 1906 and was designed by Martin Boyd, the harbourmaster at that time. The Automatic tide signalling apparatus indicated the tide's state in two ways depending on the time of day. During daylight, the level was marked with a ball and pulley system attached to the mast. At night, a number of lamps marked the tidal level. Unfortunately the building has fallen into disrepair and the mast that once stood atop it dismantled. There have been various plans to try to refurbish this unusual and unique building which so far, have come to nothing other than it has been made wind and watertight with a roof constructed.

Lady Isle[]

The town of Glasgow in c. 1776 set up a pair of beacons on Lady Isle to indicate the position of the anchorage, which was situated to the east or inshore, for the benefit of ships serving its merchants.[24] The lighthouse was built on the site of one of the beacons and the remaining 18th-century 'beacon' when aligned with the lighthouse continued to allow mariners to follow a safe course to a sheltered anchorage. In addition to providing shelter for smaller ships en route to Irvine, those with a tonnage of over 220 tons, too large to enter Irvine harbour [NS33NW 40.00] could also find anchorage in 10 to 14 fathoms [18 to 26m] in an area east of, and sheltered by Lady Isle.[25]

Robert Burns and Richard Brown[]

Captain Richard Brown, a good friend of Robert Burns, was born in Irvine, the son of a 'plain mechanic' named William Brown and his wife Jane Whinie. Richard had a wealthy patron who gave him a good education, however the patron died and his chances of bettering his situation in life were dashed. He went to sea where, after many ups and downs, he ended up being robbed by American Privateers and abandoned on the wild coast of Connaught. He had fought for the liberty of the Americans against the British, and the American struggle for freedom, obvious in the poet's early poems, the poets sympathy for the colonists can at least in part be attributed to Brown.[26]

Burns, who had lived in Irvine for around nine months, describes Richard Brown as "This gentleman's mind was fraught with courage, independence, magnanimity, and every noble manly virtue." Robert Burns wrote to Richard Brown, or Ritchie Broun, (1753–1833), on 30 December 1787, saying My will o' wisp fate, you know: do you remember a Sunday we spent together in Eglinton Woods? You told me, on my repeating some verses to you that you wondered I could resist the temptation of sending verses of such merit to a magazine.[27] Therefore, it was Richard Brown who inspired Burns and gave him the idea that he should publish his work.[28] In confirmation, Burns wrote the following to Brown, Twas actually this that gave me an idea of my own pieces which encouraged me to endeavour at the character of a Poet.

The Scottish Maritime Museum[]

The Ayrshire section of the Scottish Maritime Museum is located at Irvine harbour. In 1991 the category A listed former Engine Shop of Alexander Stephen and Sons, was salvaged and relocated to Irvine from their derelict Linthouse shipyard in Glasgow. The Linthouse engineering shop is now home to many industrial exhibits. The Boatshop on the quayside contains a small exhibition of ship models and houses a cafe. The Shipyard Workers' Tenement Flat is another attraction which portrays a typical 'room and kitchen' worker's tenement flat, restored to its 1920s appearance.

Most of the museum's floating vessels are moored at pontoons alongside Irvine Harbour. The moored ships located here vary from time to time, including the puffer Spartan, built in 1942 and typical of the puffers that were found throughout much of Western Scotland until the 1960s.

For many years, the hull of the Clipper 'Carrick' or 'City of Adelaide' was a well-known landmark, located on a slipway at the museum. In September 2013, the hull was placed on a pontoon and towed to Adelaide in Australia.

Arts and sports[]

The (HAC) is located on the Irvine Harbourside and was re-opened in 2006 following major refurbishment funded by the National Lottery and North Ayrshire Council. This facility is one of the most important cultural centres in North Ayrshire with quality exhibition areas, provision for art & drama classes, a theatre, and entertainment such as comedy, live music, special events, etc. The venue is the birthplace of Scottish touring theatre companies, Borderline, and The McDougalls. The building opened in 1965.

Located beside the HAC are the , an artist's studio complex which is the largest in South West Scotland.

Run by North Ayrshire Leisure Ltd., the former Magnum Leisure Centre provided facilities for many indoor sports, including an indoor swimming pool and sauna. The Magnum Centre was opened in 1977 as a pioneering all-inclusive leisure centre, one of the first such centres in the country. It was inspired by the Billingham Forum.[29] Following its closure in December 2016, it was demolished in July 2017.[30]

The Big Idea[]

The Big Idea building was constructed on the 1870s site of Alfred Nobel's dynamite factory. The venue was reached by the 'Bridge of Scottish Inventions' from the harbourside and its car parks. Housed within this unusual building, designed to look like a sand dune, were a lecture theatre, a restaurant, eighty or so hands-on exhibits, an invention construction area, a ride through the history of explosives, and a feature on the Nobel Prize awards. The 'Big Idea' closed in 2003 due to low visitor numbers. NPL Estates now own the building and have stated that they hope to bring the building back into use as part of a golfing development.[19]

The Irvine estuary[]

Behind the Ardeer Peninsular by far the largest estuary in Ayrshire has developed at the confluence of the Irvine and Garnock Rivers. This is one of the best examples of a bar-built estuary in the UK and is the only major estuary between the Solway and Inner Clyde. The majority of the estuary has been designated a SSSI, in recognition of its national importance for three bird species eider, red-breasted merganser and goldeneye). It is also a nationally important feeding ground for thousands of migrating birds during the spring and autumn.

Otters and water voles live on the estuary as well as numerous breeding birds, including water rail, grasshopper warbler and sand martin. The Garnock/Irvine estuary is also a Wildlife Site.[31] Bogside Flats SSSI covers 253.8ha that include inter-tidal mudflats, salt-marsh and adjacent pasture land.[32]

The Isle of Ardeer[]

The Ardeer peninsular which forms the western boundary of the estuary and harbour was once an island with a sea channel running along to exit in the vicinity of Auchenharvie Academy. A map of circa 1601, based on Timothy Ponts map of circa 1600 clearly shows a small island with the settlements of Ardeer, Dubbs, Bogend, Longford, Snodgrass, Lugton Mill and Bartonholm all being on or near the coastline. The island was small and extended no further than Bartonholm, nowhere near the size of the present day Ardeer peninsula.

The Lugton Water opened into the bay at that time and not into the Garnock.[33] A map of 1636-52 however shows the coastline as being much further inland than at present and the island of Ardeer by this time has become a peninsular.[34] Roy. It was at around this time that the old harbour at Seagatefoot was finally abandoned a new harbour built at Fullarton in 1665[11] and the extreme sand movements may have choked the sea channel that had made Ardeer an island.

As late as 1902 it was recorded that "Within recent years a number of little lochs, or dubbs, existed between Kilwinning and Stevenston, the memory of which, at least, has been preserved in the name of Dubbs Farm."[35] Ardeer House, Castlehill, Bartonholm, and Bogside were on the coast.[35] The geology of the area shows river deposits along the course of the old river bed.[36]

The Garnock and Irvine[]

The silt from these two rivers and the Annick Water have created the Bogside mudflats, however over the centuries the course of these watercourses has changed considerably due to natural, man made and according to legend, even spiritual causes. A racecourse was once located at Bogside on the mudflats.

The Curse of Saint Winning[]

A legend tells of Saint Winning sending his monks to fish in the Garnock, however no matter how hard they tried or how long they persevered they could catch nothing. The saint in response placed a curse on the river, preventing it from ever having fish in its waters; the river responded by changing course and thereby avoiding the curse. as stated above it is clear that the river has substantially changed its course in recorded history, previously having entered the sea at Stevenston. Ardeer therefore being an island at that time. Blaeu's map printed in 1654 shows this.[37]

The Garnock and the mining disaster of 1833[]

On 20 June 1833 the surface of the Garnock was seen to be ruffled and it was discovered that a section of the river bed had collapsed into mineworkings beneath. The river was now flowing into miles of mineworkings of the Snodgrass, Bartonholm and Longford collieries. Futile attempts were made to block the breach with clay, whin, straw, etc. The miners had been safely brought to the surface and were able to witness the sight of the river standing dry for nearly a mile downstream, with fish jumping about in all directions. The tide brought in sufficient water to complete the flooding of the workings and the river level returned to normal. The weight of the floodwater was so great that the compressed air broke through the ground in many places and many acres of ground were observed to bubble up like a pan of boiling water. In some places rents and cavities appeared measuring four or five feet in diameter, and from these came a roaring sound described as being like steam escaping from a safety valve. For about five hours great volumes of water and sand were thrown up into the air like fountains and the mining villages of Bartonholm, Snodgrass, Longford and Nethermains were flooded.

The 13th Earl of Eglinton purchased all the lands concerned in 1852 and through the simple solution of cutting a short canal at Bogend, across the loop of the river involved, he bypassed the breach and once the river course had been drained and sealed off he was able to have the flooded mineworkings pumped out. The breach lay on the sea side of the loop close to Bogend on the Snodgrass Holm side.[38]

Micro-history[]

The harbour and surrounding area became an area heavily blighted by industrial waste even long after some of the causer industries were gone. There was even a waste bing known by the locals as 'The Blue Billy' due to the colour of the waste dumped there.

Turf from the Bogside 'flats' was collected and sold for use on football pitches, most famously Hampden and Wembley.[39]

Sand was collected from the harbour for various uses, such as fine sand for bowling greens and coarser building sand.[15]

Alexander MacMillan (1818-1896) was born in Irvine and his father Duncan Macmillan was an Ayrshire smallholder with a few cattle, who also worked as a carter, carrying coal from the pits to Irvine harbour.

See also[]

References[]

- Notes

- ^ RCAHMS Retrieved : 2013-04-02

- ^ NPL Estates Archived 20 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2012-11-16

- ^ Strawhorn, Page 3

- ^ Simpson, Page 1

- ^ Johnston, Page 167

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f RCAHMS Retrieved : 2012-11-18

- ^ McJannet, Page 91

- ^ Jump up to: a b Muniments of the Royal Burgh of Irvine. Accessed : 2010-01-26

- ^ MacEwan, Page 5

- ^ Lindsay, Page 58

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Close, Page 55

- ^ Brown, Page 67

- ^ Jump up to: a b c MacEwan, Page 10

- ^ Hughson, Page 23

- ^ Jump up to: a b MacEwan, Page 6

- ^ MacEwan, Page 2

- ^ Harbour Master's Office Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2012-11-16

- ^ Gillespie, Page 82

- ^ Jump up to: a b Irvine Harbour Archived 22 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2012-11-16

- ^ Jump up to: a b MacEwan, Page 14

- ^ MacEwan, Page 24

- ^ Irvine Herald Retrieved : 2013-07-07

- ^ Irvine Harbourside Archived 29 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2013-07-07

- ^ Paterson, Page 420.

- ^ RCAHMS Retrieved : 2012-11-18

- ^ Irvine Burns Club Retrieved : 2012-11-17

- ^ Kilwinning 2000, page 36.

- ^ Hogg, page 58.

- ^ Close & Riches p85, 382

- ^ https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/15441680.end-of-an-era-as-demolition-teams-knock-down-the-magnum-centre/

- ^ "Ayrshire Biodiversity Action Plan, Coastal and Marine Habitats" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2005. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 038, October 2002

- ^ Blaeu's Map Retrieved : 2012-08-16

- ^ Robert Gordon's Map Retrieved : 2012-08-16

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wallace, Page 3

- ^ Geology of Ayrshire Retrieved : 2012-08-16

- ^ Blaeu's Map Accessed : 2012-11-16

- ^ Brotchie, Page 13.

- ^ MacEwan, Page 8

- Sources and further reading

- Brotchie, Alan W., Some Early Ayrshire Railways. Sou'West Journal. No. 38.

- Brown, Marilyn (2012). Scotland's Lost Gardens. Edinburgh : RCAHMS. ISBN 978-1-902419-81-7.

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. Edinburgh : Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0.

- Close, Rob & Riches, Anne (2012), Ayrshire and Arran. The Buildings of Scotland. Pevsner Architectural Guides. ISBN 978-0-300-14170-2

- Close, Robert (1992), Ayrshire and Arran: An Illustrated Architectural Guide. Pub. Roy Inc Arch Scot. ISBN 1-873190-06-9.

- Coventry, Martin (2010). Castles of the Clans. Musselburgh : Goblinshead. ISBN 1-899874-36-4.

- Cuthbertson, D. C. Autumn in Kyle and the Charm of Cunninghame. London : Herbert Jenkins.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow: John Tweed.

- Gillespie, James H. (1939). Dundonald. A Contribution to parochial History. Glasgow : John Wylie & Co.

- Hughson, Irene (1996). The Auchenharvie Colliery an Early History. Ochiltree : Richard Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 1-872074-58-8.

- Ingram, John (1844). The Spectre Huntsman. The Ayrshire Wreath MDCCCXLIV.

- Johnston, J. B. (1903). Place-names of Scotland. Edinburgh : David Douglas.

- Lindsay, Maurice (1964). The Discovery of Scotland. London : Robert Hale.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- McEwan, Mae (Editor) 1985. The Harbour - Fullarton Folk Reminisce. Irvine : Fullarton Historical Society.

- McJannet, A (1938). Royal Burgh of Irvine.

- Paterson, James (1866). History of the Counties of Ayrs and Wigton. Vol. IV. Cuninghame. Parts 1 & 2. Edinburgh : James Stillie.

- Robertson, George (1823). A Genealogical Account of the Principal Families in Ayrshire, more particularly in Cunninghame. Irvine.

- Salter, Mike (2006). The Castles of South-West Scotland. Malvern : Folly. ISBN 1-871731-70-4.

- Simpson, Anne Turner & Stevenson, Sylvia (1980). Historic Irvine. the archaeological implications of development. Scottish Burgh Survey. Glasgow University.

- Strachan, Mark (2009). Saints, Monks and Knights. North Ayrshire Council. ISBN 978-0-9561388-1-1.

- Strawhorn, John (1994). The History of Irvine. Edinburgh : John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-140-1.

External links[]

- Commentary and video of the old Harbourmaster's Office

- Commentary and video of Seagate Castle, Irvine.

- A video and commentary on the Bogside saltmarsh and mudflats

- A video and commentary on the Irvine Estuary.

- The Ardeer Headland, old explosives factory site and the old 'Big Idea' building.

- YouTube video of Irvine harbour entrance from the Ardeer Peninsula

- YouTube video of the Carrick / City of Adelaide Clipper at Irvine

- YouTube video of the Boyd Automatic Tide Indicator apparatus

- YouTube video of the Boyd Automatic Tide Indicator apparatus from the Ardeer Peninsula

- Irvine Harbourside Project Website

- Irvine Burns Club Website

- Harbour Arts Centre

- The Irvine Harbour Company

- Scottish Maritime Museum

- The Magnum

- Irvine Scotland Website

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Irvine Harbour. |

- Castles in North Ayrshire

- Buildings and structures in North Ayrshire

- Geography of North Ayrshire

- Archaeological sites in North Ayrshire

- History of North Ayrshire

- Irvine, North Ayrshire