Islam in Bangladesh

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 135.4 million (90.4%) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout Bangladesh | |

| Religions | |

| Predominantly Sunni Muslims | |

| Languages | |

| Bengali, Urdu (minority) and Arabic (liturgical)[5] |

| Islam in Bangladesh | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| History | ||||||

|

||||||

| Culture | ||||||

|

||||||

| Major figures | ||||||

|

||||||

| Communities | ||||||

| Ideology/schools of thought | ||||||

|

||||||

| Educational organizations and institutions | ||||||

|

||||||

| Influential bodies | ||||||

|

||||||

| Other topics | ||||||

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Islam is the state religion of the People's Republic of Bangladesh.[6][7] As per 2011 census, Bangladesh recorded a population of 149,772,364 people, of which the Muslim population was approximately 135,394,217, constituting an overwhelming 90.4% of the country's population,[8][9][10] making Bangladesh the third-largest Muslim majority nation in the world after Indonesia and Pakistan. The majority of Bangladeshis are Sunni, and follow the Hanafi Islamic jurisprudence. Religion is an integral part of Bangladeshi identity. Despite having a Muslim-majority Bangladesh is a secular state.[11]

In the 9th century, Arab Muslims established commercial as well as religious connection within the region before the conquest, mainly through the coastal regions as traders and primarily via the ports of Chittagong. Arab navigation in the region was the result of the Muslim reign over the Indus delta. Following the conquests of Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate, Indian Islamic missionaries came in this region safely and achieved one of their greatest success in terms of successful dawah and number of converts to Islam in Bengal.[12][13][14] Sufi's like Shah Jalal are thought to have spread Islam in the north-eastern Bengal and Assam during the beginning of the 12th century. The Islamic Bengal Sultanate, a major trading nation in the world, was founded by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah after its independence from the Tughlaq dynasty. Bengal reached in her golden age during Bengal Sultanate's ruling period. Subsequently, Bengal was conquered by Babur, the founder of one of the gunpowder empires, but was also briefly occupied by the Suri Empire.

Akbar the Great's preaching of the syncretic Din-i Ilahi, was described as a blasphemy by the Qadi of Bengal, which caused huge controversies in South Asia. In the 17th century, under Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb's Islamic sharia-based rule,[15] the Bengal Subah, also known as The Paradise of the Nations,[16] was worth over 12% of global GDP and one of the world's leading manufacturing power, from which the Dutch East India Company hugely benefited.[17][18][19] Concepts of the Islamic economics's found in the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri delivered a significant direct contribution to the economy of Bengal, and the Proto-industrialization was signaled.[20]

History[]

Early explorers[]

The Buddhist Pala Empire enjoyed relations with the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. Islam first appeared in Bengal during Pala rule, as a result of increased trade with the early Arab Muslim merchants in places such as the Port of Chittagong.[21] Around this time, the Arab geographer Al-Masudi and author of The Meadows of Gold, travelled to the region where he noticed a Muslim community of inhabitants residing in the region.[22] Other authentications of the Arab traders present in the region was the writings of Arab geographers found on the Meghna River located near Sandwip on the Bay of Bengal. This evidence suggests that the Arab traders had arrived along the Bengal coast long before the Turkic conquest. The Arab writers also knew about the kingdoms of Samrup and Rumi, the latter being identified with the empire of Dharmapal of the Pala Empire. The earliest mosque in South Asia is possibly in Lalmonirhat, built during or just after the Prophet Muhammad's lifetime.[23]

In addition to trade, Islam was also being introduced to the people of Bengal through the migration of missionaries prior to conquest. Arab navigation eastwards was the result of the Muslim reign in North India.[24] The earliest known Sufi missionaries were Syed Shah Surkhul Antia and his students, most notably Shah Sultan Rumi, who arrived in 1053 CE. Rumi settled in present-day Netrokona, Mymensingh where he influenced the local ruler and population to embrace Islam.

The first Muslim conquest of Bengal was undertaken by the forces of General Bakhtiyar Khilji in the thirteenth century. This opened the doors for Muslim influence in the region for hundreds of years up until the present-day.[24] Many of the people of Bengal began accepting Islam through the influx of missionaries following this conquest. Sultan Balkhi and Shah Makhdum Rupos settled in the present-day Rajshahi Division in northern Bengal, preaching to the communities there. Numerous small sultanates emerged in the region. During the reign of the Sultan of Lakhnauti Shamsuddin Firuz Shah, much of present-day Satgaon, Sonargaon and Mymensingh came under Muslim dominion. A community of 13 Muslim families headed by Burhanuddin resided in the northeastern city of Srihatta (Sylhet), claiming their descendants to have arrived from Chittagong.[25] Srihatta (Sylhet) was ruled by an oppressive king called Gour Govinda. After being informed of Raja Gour Govinda's oppressive regime in Sylhet, Firuz Shah sent numerous forces led by his nephew Sikandar Khan Ghazi and subsequently his military commander-in-chief Syed Nasiruddin to conquer Sylhet. By 1303, over three hundred Sufi preachers led by Shah Jalal aided the conquest and confirmed a victory. Following the conquest, Jalal disseminated his followers across different parts of Bengal to spread Islam. Jalal is now a household name among Muslims in Bangladesh.[26]

As independent Sultanate of Bengal[]

During the Sultanate period, a syncretic belief system arose due to mass conversions.[27] As a result, the Islamic concept of tawhid (the oneness of God) was diluted into the veneration of saints or pirs. Deities such as Shitala (goddess of smallpox), Olabibi (goddess of cholera) and Manasa (goddess of snakes) became venerated as pirs.[28]

Under Mughal Empire[]

In pre-Mughal times, there is less evidence for widespread adoption of Islam in what is now Bangladesh. What mention of Muslims there was usually in reference to an urban elite. Ibn Battuta met with Shah Jalal in Sylhet and noted the inhabitants of the plains were still Hindu. In 1591, Venetian traveller Cesare Federici mentioned Sondwip near Chittagong as having an entirely Muslim population. The seventeenth century European travellers generally understood Islam as being implanted after the Mughal conquest.[29]

During the Mughal Empire, much of the region of what is now East Bengal was still heavily forested, but highly fertile. The Mughals incentivised the bringing of this land under cultivation, and so peasants were incentivised to bring the land under cultivation. These peasants were primarily led by Muslim leaders and so Islam became the main religion in the delta. Most of the Zamindars in the modern Barisal division, for instance, were upper caste Hindus who subcontracted actual jungle clearance work to a Muslim pir. In other instances, pirs themselves would organise the locals to clear the jungle and then contact the Mughals to gain legitimacy. In other instances, such as the densely-forested interior of Chittagong, Muslims came from indigenous tribals who never followed Hindu rituals.[29]

In British India[]

The British East India Company was given the right to collect revenue from Bengal-Bihar by the treaty of Allahabad after defeating the combined armies of Nawab Mir Qasim of Bengal, Nawab of Awadh and Mughal emperor at the Battle of Buxar. They annexed Bengal in 1793 after abolishing local rule (Nizamat). The British looted the Bengal treasury, appropriating wealth valued at US$40 billion in modern-day prices.[30] Due to high colonial taxation, Bengali commerce shrank by 50% within 40 years, while at the same time British imports flooded the market. Spinners and weavers starved during famines and Bengal's once industrious cities became impoverished. The East India Company forced opium and indigo cultivation and the permanent settlement dismantled centuries of joint Muslim-Hindu political, military and feudal cooperation.[citation needed]

The Bengal Presidency was established in 1765. Rural eastern Bengal witnessed the earliest rebellions against British rule, including the Faraizi movement led by Haji Shariatullah and the activities of Titumir. The mutiny of 1857 engulfed much of northern India and Bengal, including in Dhaka and Chittagong.[31][32] Following the end of the mutiny the British Government took direct control of Bengal from the East India Company and instituted the British Raj. The influence of Christian missionaries increased in this period. To counter this trend, Reazuddin Ahmad Mashadi, Muhammad Reazuddin Ahmad[33] of the Sudhakar newspaper and Munshi Mohammad Meherullah played prominent roles.[34]

The colonial capital Calcutta, where Bengali Muslims formed the second largest community, became the second largest city in the British Empire after London. The late 19th and early 20th-century Indian Renaissance brought dramatic social and political change. The introduction of Western law, government and education introduced modern enlightenment values which created a new politically conscious middle class and a new generation of leaders in science, politics and the arts. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan pioneered English education among British Indian Muslims, with many Bengali Muslims enrolling in Aligarh Muslim University. The First Partition of Bengal incubated the broader anti-colonial struggle and in 1906 the All India Muslim League was formed during the Muhammadan Education Conference in Dhaka. During this period a Muslim middle class emerged[35] and the University of Dhaka played a role at the beginning of the emancipation of Bengali Muslim society, which was also marked by the emergence progressive groups like the Freedom of Intellect Movement and the Muslim Literary Society.[citation needed] Bengali Muslims were at the forefront of the Indian Independence Movement, including the Pakistan Movement for the rights of minorities.[citation needed]

Bangladesh War of Independence[]

Islamic sentiments powered the definition of nationhood in the 1940s when Bengalis united with Muslims in other parts of the subcontinent to form Pakistan. Defining themselves first as Muslims they envisaged a society based on Islamic principles. However, by the beginning of the 1970s the Bengalis were more swayed by regional feelings, in which they defined themselves foremost as Bengalis before being Muslims. The society they then envisioned was based on western principles such as secularism and democracy. While Islam was still a part of faith and culture, it no longer informed national identity.[36]

The phenomenon both before and after the independence of Bangladesh was that the concept of an Islamic state received more support from West Pakistanis than from East Pakistanis. Bangladesh was established as a secular state[37] and the Bangladeshi constitution enshrined secular and democratic principles.[38]

Denominations[]

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Self published sources on "Quranists". (March 2016) |

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (March 2016) |

The majority of Muslims in Bangladesh are Sunni, although other Muslim demographics within Bangladesh include Shiites, Quranists, Ahmadis, Mahdavia and non-denominational Muslims.

Sunni[]

As with the rest of the Indian subcontinent, the majority of Muslims in Bangladesh are traditional Sunni, who mainly follow the Hanafi school of jurisprudence (madh'hab) and consequently the Maturidi school of theology.[40][41] They are divided into Ahle Sunni Barelvi who support love and honor for Prophet of Islam and follow Sufi observes Mawlid. Ahle Sunnat Barelvi constitutes majority of Bangladeshi Muslims.[42] The Deobandi who do not support such practices. Non-traditional Sunnis who are not Hanafi such as the Salafi or Wahhabi have a significant community in Bangladesh and are known as Ahl-e-Hadith. There are others such as Jamaat-e-Islami, a political party similar to Muslim Brotherhood in promoting Islamism.

Sufism[]

A majority of Bangladeshi Muslims perceive Sufis as a source of spiritual wisdom and guidance and their Khanqahs and Dargahs as nerve centers of Muslim society[43] and according to an estimate approximately 26% of Bangladeshi Muslims openly identify themselves with a Sufi order, almost half of whom adhere to the Chishti order that became popular during the Mughal times, although the earliest Sufis in Bengal, such as Shah Jalal, belonged to the Suhrawardiyya order, whose global center is still Maner Sharif in Bihar.[44] During the Sultanate period, Sufis emerged[27] and formed khanqahs and dargahs that served as the nerve center of local communities.[43] The tradition of Islamic mysticism known as Sufism appeared very early in Sunni Islam and became essentially a popular movement emphasizing worship out of a love of Allah.[45][46] Sufism stresses a direct, unstructured, personal devotion to God in place of the ritualistic, outward observance of the faith and "a Sufi aims to attain spiritual union with God through love".[45][46] An important belief in the Sufi tradition is that the average believer may use spiritual guides in his pursuit of the truth.[46] Throughout the centuries many gifted scholars and numerous poets have been inspired by Sufi ideas and the Baul musical tradition of Bengal has also been influenced by Sufism.[47][48][46]

The Chishti Order, Qadiriyya, Kubrawiyya, Suhrawardiyya, Maizbhandaria, Naqshbandi, Mujaddidi, Ahmadi, Mohammadi and Rifai orders were among the most widespread Sufi orders in Bangladesh in the late 1980s.[49] The Barelvi, who support Sufism, outnumber the Deobandi in Bangladesh and South Asia although not all ordinary Barelvi adherents formally join a Sufi order.

According to FirstPost, Sufis have suffered from religious sectarianism, with fourteen Sufis murdered by Islamist extremists from December 2014 to June 2016.[50]

Revivalism[]

The influence of conservative Sunni Islam 'revivalism' has been noted by some. On 5 May 2013 a demonstration organized by the Deobandi organization known as the Hefazat-e-Islam movement paralyzed the city of Dhaka when half a million people demanded the institution of a conservative religious program, to include a ban on mixing of men and women in public places, the removal of sculptures and demands for the retention of "absolute trust and faith in Almighty Allah" in the preamble of the constitution of Bangladesh.[51] In 2017 author K. Anis Ahmed complained that attacks on and killings of liberal bloggers, academics and religious minorities,[52] had been brought about by "a significant shift ... in the past few decades" up to 2017 in attitudes towards religion in Bangladesh.

During my school years in the 1980s, religion was a matter of personal choice. No one batted an eyelid if you chose not to fast during Ramadan. Today, eat in public during the holiday and you may be chided by strangers. Thanks to shows on cable TV, social media and group meetings, Islamists have succeeded to an alarming degree in painting secularism as a threat to Islam.[52]

Ahmed and others also attacked the deletion of non-Muslim writers in the new 2017 primary school textbooks,[52] alleging they were dropped "per the demand" of Hefajat-e Islam and the Awami Olema League who had demanded "the exclusion of some of the poems written by `Hindus and atheists`".[53] These changes, as well as such errors as spelling mistakes and the incorrect arrangement of paragraphs, triggered newspaper headlines and protests on social media.[53][54] According to Prof. Akhtaruzzaman, head of the textbook committee, the omissions happened "mainly because the NCTB did the job in such a hurry that the authors and the editors got little time to go through the texts." The Primary and Mass Education Minister Mostafizur Rahman has promised the errors will be corrected.[54]

There have also been attacks on Sufi preachers and personalities by puritanical/revivalist groups.[55][56]

Small minorities[]

There are also few Shi'a Muslims, particularly belonging to the Bihari community. The Shi'a observance commemorating the martyrdom of Ali's sons, Hasan and Husayn, are still widely observed by the nation's Sunnis,[46] even though there are small numbers of Shi'as. Among the Shias, the Dawoodi Bohra community is concentrated in Chittagong.[57]

There are no adherents of the Kharijite sect in Bangladesh except foreigners such as Omani diplomats and workers at Omani missions residing in Bangladesh. Muslims who reject the authority of hadith, known as Quranists, are present in Bangladesh, though having not expressed publicly but are active virtually due to fear of gruesome persecution considering the present political situation. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, which is widely considered to be non-Muslim by mainstream Muslim leaders, is estimated to be around 100,000, the community has faced discrimination because of their beliefs and have been persecuted in some areas.[58] There is a very small community of Bangladeshis whom are adherents to the Mahdavia creed.[59] There are some people who do not identify themselves with any sect and just call themselves Muslims. They are known as non-denominational Muslims and are few in numbers although many Sunnis in Bangladesh also call themselves Muslims only and do not emphasize themselves being Sunni.

Demography[]

| Year | Percentage (%) | Muslim Population ( |

Total population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 66.1 | 19,121,160 | 28,927,626 | |

| 1911 | 67.2 | 21,205,203 | 31,555,363 | Before partition |

| 1921 | 68.1 | 22,646,387 | 33,254,607 | |

| 1931 | 69.5 | 24,744,911 | 35,604,189 | |

| 1941 | 70.3 | 29,525,452 | 41,999,221 | |

| 1951 | 76.9 | 32,346,033 | 42,062,462 | During Pakistan period |

| 1961 | 80.4 | 40,847,150 | 50,804,914 | |

| 1974 | 85.4 | 61,042,675 | 71,478,543 | After independence of Bangladesh |

| 1981 | 86.7 | 75,533,462 | 87,120,487 | |

| 1991 | 88.3 | 93,881,726 | 106,315,583 | |

| 2001 | 89.6 | 110,406,654 | 123,151,871 | |

| 2011 | 90.4 | 135,394,217 | 149,772,364 |

The population of Bangladesh have gone up from 28.92 million in 1901 to 149.77 million in 2011, as per as statistics the same way the high fertility rate among Muslims have led to over population of the country as according to census, Muslim population have gone up from 19.12 million in 1901 to 135.39 million in 2011. The Muslim percentage have also got increased from 66.1% in 1901 to 90.4% in 2011.[63]

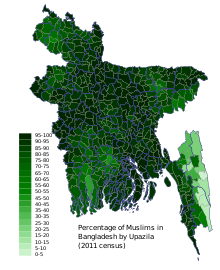

Muslim population by decades, districts and division[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 19,121,160 | — |

| 1911 | 21,205,203 | +10.9% |

| 1921 | 22,646,387 | +6.8% |

| 1931 | 24,744,911 | +9.3% |

| 1941 | 29,525,452 | +19.3% |

| 1951 | 32,346,033 | +9.6% |

| 1961 | 40,847,150 | +26.3% |

| 1974 | 61,042,675 | +49.4% |

| 1981 | 75,533,462 | +23.7% |

| 1991 | 93,881,726 | +24.3% |

| 2001 | 110,406,654 | +17.6% |

| 2011 | 135,394,217 | +22.6% |

| Source: God Willing: The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh by Ali Riaz, p. 63 Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS)[11][64] | ||

The Muslim population in Bangladesh is 135,394,217 covering up 90.4% of Bangladesh population as per 2011 census.[65] Estimation shows that over 1 million Rohingya Muslim refugees live in Bangladesh who have came here during the period of (2016–17) crisis.[66] On 28 September 2018, at the 73rd United Nations General Assembly, Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina said there are 1.1-1.3 million Rohingya refugees now in Bangladesh.[67][68]

According to Pew research center, Muslim population of Bangladesh will reach 182.36 million by the year of 2050 and will constitute 91.7% of the country's population and thus making the country 5th largest Muslim populated around that time.[69]

| Division | Muslim Population ( |

Total population | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barisal | 7,446,907 | 8,248,404 | 90.28 |

| Chittagong | 25,460,202 | 28,423,019 | 89.58 |

| Dhaka | 33,804,739 | 36,433,505 | 92.78 |

| Khulna | 13,617,984 | 15,687,759 | 86.81 |

| Mymensingh | 10,462,699 | 10,990,913 | 95.19 |

| Rajshahi | 17,248,861 | 18,484,858 | 93.31 |

| Rangpur | 13,581,967 | 15,787,758 | 86.03 |

| Sylhet | 8,482,255 | 9,910,219 | 85.59 |

| District | Muslim population ( |

Total population | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barguna | 822,652 | 892,781 | 92.14 |

| Barisal | 2,040,088 | 2,324,310 | 87.77 |

| Bhola | 1,715,497 | 1,776,795 | 96.55 |

| Jhalokati | 613,750 | 682,669 | 89.90 |

| Patuakhali | 1,350,968 | 1,460,781 | 92.48 |

| Pirojpur | 903,952 | 1,111,068 | 81.36 |

| Bandarban | 197,087 | 388,335 | 50.75 |

| Brahmanbaria | 2,627,810 | 2,840,498 | 92.51 |

| Chandpur | 2,269,246 | 2,416,018 | 93.93 |

| Chittagong | 6,618,657 | 7,616,352 | 86.9 |

| Comilla | 5,123,410 | 5,387,288 | 95.1 |

| Cox's Bazar | 2,151,958 | 2,289,990 | 93.97 |

| Feni | 1,352,866 | 1,437,371 | 94.12 |

| Khagrachhari | 274,258 | 613,917 | 44.67 |

| Lakshmipur | 1,669,495 | 1,729,188 | 96.55 |

| Noakhali | 2,965,950 | 3,108,083 | 95.43 |

| Rangamati | 209,465 | 595,979 | 35.15 |

| Dhaka | 11,400,096 | 12,043,977 | 94.65 |

| Faridpur | 1,731,133 | 1,912,969 | 90.49 |

| Gazipur | 3,200,383 | 3,403,912 | 94.02 |

| Gopalganj | 805,115 | 1,172,415 | 68.67 |

| Kishoreganj | 2,752,007 | 2,911,907 | 94.51 |

| Madaripur | 1,023,702 | 1,165,952 | 87.8 |

| Manikganj | 1,262,215 | 1,392,867 | 90.62 |

| Munshiganj | 1,328,838 | 1,445,660 | 91.92 |

| Narayanganj | 2,802,567 | 2,948,217 | 95.06 |

| Narsingdi | 2,098,829 | 2,224,944 | 94.33 |

| Rajbari | 942,957 | 1,049,778 | 89.82 |

| Shariatpur | 1,114,301 | 1,155,824 | 96.41 |

| Tangail | 3,342,596 | 3,605,083 | 92.72 |

| Bagerhat | 1,198,593 | 1,476,090 | 81.2 |

| Chuadanga | 1,100,330 | 1,129,015 | 97.46 |

| Jessore | 2,446,162 | 2,764,547 | 88.48 |

| Jhenaidah | 1,601,086 | 1,771,304 | 90.39 |

| Khulna | 1,776,749 | 2,318,527 | 76.63 |

| Kushtia | 1,888,744 | 1,946,838 | 97.02 |

| Magura | 753,199 | 918,419 | 82.01 |

| Meherpur | 640,751 | 655,392 | 97.77 |

| Narail | 586,588 | 721,668 | 81.28 |

| Satkhira | 1,625,782 | 1,985,959 | 81.86 |

| Jamalpur | 2,252,181 | 2,292,674 | 98.23 |

| Mymensingh | 4,895,267 | 5,110,272 | 95.79 |

| Netrokona | 2,001,732 | 2,229,642 | 89.78 |

| Sherpur | 1,313,519 | 1,358,325 | 96.7 |

| Bogra | 3,192,728 | 3,400,874 | 93.88 |

| Chapai Nawabganj | 1,571,151 | 1,647,521 | 95.36 |

| Joypurhat | 819,235 | 913,768 | 89.65 |

| Naogaon | 2,250,427 | 2,600,157 | 86.55 |

| Natore | 1,590,919 | 1,706,673 | 93.22 |

| Pabna | 2,445,702 | 2,523,179 | 96.93 |

| Rajshahi | 2,430,194 | 2,595,197 | 93.64 |

| Sirajganj | 2,948,505 | 3,097,489 | 95.19 |

| Dinajpur | 2,333,253 | 2,990,128 | 78.03 |

| Gaibandha | 2,205,539 | 2,379,255 | 92.7 |

| Kurigram | 1,932,779 | 2,069,273 | 93.4 |

| Lalmonirhat | 1,080,512 | 1,256,099 | 86.02 |

| Nilphamari | 1,538,916 | 1,834,231 | 83.9 |

| Panchagarh | 820,629 | 987,644 | 83.09 |

| Rangpur | 2,604,263 | 2,881,086 | 90.39 |

| Thakurgaon | 1,066,076 | 1,390,042 | 76.69 |

| Habiganj | 1,731,168 | 2,089,001 | 82.87 |

| Maulvibazar | 1,425,786 | 1,919,062 | 74.3 |

| Sunamganj | 2,144,535 | 2,467,968 | 86.89 |

| Sylhet | 3,180,766 | 3,434,188 | 92.62 |

Percentage of Muslims in Bangladesh by decades[64]

| Year | Percent | Increase |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 66.1% | - |

| 1911 | 67.2% |

+1.1% |

| 1921 | 68.1% |

+0.9% |

| 1931 | 69.5% |

+1.4% |

| 1941 | 70.3% |

+0.8% |

| 1951 | 76.9% |

+6.6% |

| 1961 | 80.4% | +3.5% |

| 1974 | 85.4% | +5% |

| 1981 | 86.7% | +1.3% |

| 1991 | 88.3% | +1.6% |

| 2001 | 89.6% | +1.3% |

| 2011 | 90.4% | +0.8% |

Islamic culture in Bangladesh[]

Although Islam played a significant role in the life and culture of the people, religion did not dominate national politics because Islam was not the central component of national identity.[46] When in June 1988 an "Islamic way of life" was proclaimed for Bangladesh by constitutional amendment, very little attention was paid outside the intellectual class to the meaning and impact of such an important national commitment.[46] However, most observers believed that the declaration of Islam as the state religion might have a significant impact on national life.[46] Aside from arousing the suspicion of the non-Islamic minorities, it could accelerate the proliferation of religious parties at both the national and the local levels, thereby exacerbating tension and conflict between secular and religious politicians.[46] Unrest of this nature was reported on some college campuses soon after the amendment was promulgated.[46]

Islamic architecture in Bangladesh[]

Mosques[]

Bangladesh has a vast amount of historic mosques with its own Islamic architecture.

- Abu Aqqas Mosque-648[71][72]

- Shahbaz Khan Mosque-1679

- Shona Mosque-1493

- Bagha Mosque-1523

- Khan Mohammad Mridha Mosque-1703

- Sixty Dome Mosque -15th century

Modern mosques[]

Tombs and mausoleums[]

Lalbagh Fort-1664

Law and politics[]

hideThis section has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Legal issues[]

In Bangladesh, where a modified Anglo-Indian civil and criminal legal system operates, there are no official sharia courts.[46] Most Muslim marriages, however, are presided over by the qazi, a traditional Muslim judge whose advice is also sought on matters of personal law, such as inheritance, divorce, and the administration of religious endowments.[46]

The inheritance rights of Muslim in Bangladesh are governed by The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act (1937)[73] and The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961).[74] Article 2 of The Muslim Personal Law Application Act provides that questions related to succession and inheritance are governed by Muslim Personal Law (Shariat).[73][75] Article 2 proclaims: "any custom or usage to the contrary, in all questions (save questions relating to agricultural land) regarding intestate succession, special property of females, including personal property inherited or obtained under contract or gift or any other provision of Personal Law, marriage, dissolution of marriage, including talaq, ila, zihar, lian, khula and mubaraat, maintenance, dower, guardianship, gifts, trusts and trust properties, and waqfs (other than charities and charitable institutions and charitable and religious endowments) the rule of decision in cases where the parties are Muslims shall be the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat)."[73]

Political issues[]

Post-1971 regimes sought to increase the role of the government in the religious life of the people.[46] The Ministry of Religious Affairs provided support, financial assistance, and endowments to religious institutions, including mosques and community prayer grounds (idgahs).[46] The organization of annual pilgrimages to Mecca also came under the auspices of the ministry because of limits on the number of pilgrims admitted by the government of Saudi Arabia and the restrictive foreign exchange regulations of the government of Bangladesh.[46] The ministry also directed the policy and the program of the Islamic Foundation Bangladesh, which was responsible for organizing and supporting research and publications on Islamic subjects.[46] The foundation also maintains the Baitul Mukarram (National Mosque), and organized the training of imams.[46] Some 18,000 imams were scheduled for training once the government completed establishment of a national network of Islamic cultural centers and mosque libraries.[46] Under the patronage of the Islamic Foundation, an encyclopedia of Islam in the Bengali language was being compiled in the late 1980s.[46]

Another step toward further government involvement in religious life was taken in 1984 when the semiofficial Zakat Fund Committee was established under the chairmanship of the president of Bangladesh.[46] The committee solicited annual zakat contributions on a voluntary basis.[46] The revenue so generated was to be spent on orphanages, schools, children's hospitals, and other charitable institutions and projects.[46] Commercial banks and other financial institutions were encouraged to contribute to the fund.[46] Through these measures the government sought closer ties with religious establishments within the country and with Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan.[46]

Leaders and organizations[]

The members of the Ulama include Mawlānā, Imams, Ulama and Muftis.[46] The first two titles are accorded to those who have received special training in Islamic theology and law.[46] A maulvi has pursued higher studies in a madrassa, a school of religious education attached to a mosque. Additional study on the graduate level leads to the title Mawlānā.[46]

Educational institutions[]

The madrassas are also ideologically divided in two mainstreams.The Ali'a Madrassa which has its roots in Aligarh Movement of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan Bahadur and the other one is Qawmi Madarassa.

Status of religious freedom[]

The Constitution establishes Islam as the state religion but upholds the right to practice—subject to law, public order, and morality—the religion of one's choice.[76] The Government generally respects this provision in practice. The Government (2001–2006) led by an alliance of four parties Bangladesh Nationalist Party, Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh, Islami Oikya Jote and Bangladesh Jatiyo Party banned Ahmadiya literature by an executive order. However, the present government, led by Bangladesh Awami League strongly propagates secularism and respect towards other religions. Despite all Bangladeshis saying that religion is an important part of their daily lives, Bangladesh's Awami League won a landslide victory in 2008 on a platform of secularism, reform, and a suppression of radical Islamist groups. According to a Gallup poll conducted in 2009, simultaneous strong support of the secular Awami League and the near unanimous importance of religion in daily life suggests that while religion is vital in Bangladeshis' daily lives, they appear comfortable with its lack of influence in government.[77]

In Bangladesh, the International Crimes Tribunal tried and convicted several leaders of the Islamic Razakar militias, as well as Bangladesh Muslim Awami league (Forid Uddin Mausood), of war crimes committed against Hindus during the 1971 Bangladesh genocide. The charges included forced conversion of Bengali Hindus to Islam.[78][79][80]

See also[]

- Islam in West Bengal

- Islam in South Asia

- Islam by country

- Muslim Population by District in West Bengal

References[]

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20110807044722/http://www.bbs.gov.bd/Home.aspx

- ^ https://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/muslims/

- ^ "Bangladesh 2015 International Religiou Freedom Report" (PDF). U.S. Department of State.

- ^ "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2011-05-30). "Polygenesis in the Arabic Dialects". Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. BRILL. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_SIM_000030. ISBN 9789004177024.

- ^ Bergman, David (28 Mar 2016). "Bangladesh court upholds Islam as religion of the state". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Bangladesh dismisses case to drop Islam as state religion". Reuters. 28 March 2016.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20110807044722/http://www.bbs.gov.bd/Home.aspx

- ^ https://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/muslims/

- ^ "National Volume - 2: Union Statistics" (PDF). Population and Housing Census. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Statistics Bangladesh 2006" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-21. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- ^ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pp. 227-228

- ^ Majumdar, Dr. R.C., History of Mediaeval Bengal, First published 1973, Reprint 2006, Tulshi Prakashani, Kolkata, ISBN 81-89118-06-4

- ^ "How Islam and Hadith Entered Bangladesh". ilmfeed. 26 March 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Jackson, Roy (2010). Mawlana Mawdudi and Political Islam: Authority and the Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 9781136950360.

- ^ "The paradise of nations | Dhaka Tribune". Archive.dhakatribune.com. 2014-12-20. Archived from the original on 2017-12-16. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ^ M. Shahid Alam (2016). Poverty From The Wealth of Nations: Integration and Polarization in the Global Economy since 1760. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-333-98564-9.

- ^ Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed).

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2003): Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics, OECD Publishing, ISBN 9264104143, pages 259–261

- ^ Hussein, S M (2002). Structure of Politics Under Aurangzeb 1658-1707. Kanishka Publishers Distributors. p. 158. ISBN 978-8173914898.

- ^ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. Discovery Publishing House. p. 199. ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0.

- ^ Al-Masudi, trans. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille (1962). "1:155". In Pellat, Charles (ed.). Les Prairies d'or [Murūj al-dhahab] (in French). Paris: Société asiatique.

- ^ "Ancient mosque unearthed in Bangladesh". Al Jazeera English. 2012-08-18. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Islam in Bangladesh". Global Front. Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2008-02-14.[self-published source?]

- ^ Qurashi, Ishfaq (December 2012). "বুরহান উদ্দিন ও নূরউদ্দিন প্রসঙ্গ" [Burhan Uddin and Nooruddin]. শাহজালাল(রঃ) এবং শাহদাউদ কুরায়শী(রঃ) [Shah Jalal and Shah Dawud Qurayshi] (in Bengali).

- ^ Abdul Karim (1959). Social History Of The Muslims In Bengal (Down to A.D. 1538). Dacca: The Asiatic Society of Pakistan. p. 100.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eaton, Richard M. (1993). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760 (PDF). Berkeley: University of California Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-21. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Banu, U.A.B. Razia Akter (1992). Islam in Bangladesh. New York: BRILL. pp. 34–35. ISBN 90-04-09497-0. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eaton, Richard M. (1993-12-31). Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. doi:10.1525/9780520917774. ISBN 9780520917774.

- ^ "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star. 2015-07-31.

- ^ Pandey, Jhimli Mukherjee (10 June 2009). "Rare 1857 reports on Bengal uprisings". The Times of India.

- ^ Khan, Alamgir (14 July 2014). "Revisiting the Great Rebellion of 1857". The Daily Star.

- ^ "Ahmad, Muhammad Reazuddin". Banglapedia. Bangladesh Asiatic Society. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth W. (1992). Religious Controversy in British India: Dialogues in South Asian Languages. New York: SUNY Press. pp. 94–96. ISBN 0791408280. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Mukhopadhay, Keshob. "An interview with prof. Ahmed sharif". News from Bangladesh. Daily News Monitoring Service. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ^ Willem van Schendel (12 February 2009). A History of Bangladesh. Cambridge University Press. p. 183. ISBN 9780511997419.

- ^ Baxter, Craig (1997). Bangladesh: From A Nation To A State. Westview Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-813-33632-9.

- ^ Baxter, Craig (1997). Bangladesh: From A Nation To A State. Westview Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-813-33632-9.

- ^ "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2012-08-09. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- ^ "Hanafi Islam".

- ^ "Islamic Family Law » Bangladesh, People's Republic of". Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/jaipur/noted-sufi-heads-denounce-fatwa-issued-by-barelvis/articleshow/51608463.cms

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clinton Bennett; Charles M. Ramsey (1 March 2012). South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-3589-6.

- ^ "Religious Identity Among Muslims". 2012-08-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burke, Thomas Patrick (2004). The major religions: An Introduction with Texts. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 280. ISBN 1-4051-1049-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Blood, Peter R. (1989). "Islam". In Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert L (eds.). Bangladesh: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 73–78. OCLC 49223313.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.CS1 maint: postscript (link)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.CS1 maint: postscript (link)

- ^ Shah, Idries (1991) [First published 1968]. The Way of the Sufi. Penguin Arkana. pp. 13–52. ISBN 0-14-019252-2. References to the influence of the Sufis, see Part One: The Study of Sufism in the West, and Notes and Bibliography.

- ^ Shah, Idries (1999) [First published 1964]. The Sufis. Octagon Press Ltd. pp. all. ISBN 0-86304-074-8. References to the influence of the Sufis scattered throughout the book.

- ^ "Sufism Journal: Community: Sufism in Bangladesh". sufismjournal.org.[self-published source?]

- ^ "Sufis in Bangladesh now live in fear after several machete killings". Firstpost. 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2017-02-16.

- ^ "Bangladesh | The World Almanac of Islamism". almanac.afpc.org. Retrieved 2017-02-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c AHMED, K. ANIS (3 February 2017). "Bangladesh's Creeping Islamism". New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Under fire, NCTB moves to fix textbook errors". The Daily Star. 7 January 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Textbook embarrassments: The strange mistakes on schoolbooks". bdnews24.com. 9 January 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2014/aug/28/faruqi-killing-ahle-sunnat-blames-wahabi-moududi-followers#sthash.6OGea7I0.dpuf

- ^ http://www.firstpost.com/living/sufis-in-bangladesh-now-live-in-fear-after-several-machete-killings-2813880.html

- ^ Ferdousi, Ishrat. "Yasmin Farzana Shafi". The Daily Star. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Bangladesh Religious Freedom 2007". US Department of State. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ^ Bhargava, Rajeev. "Inclusion and Exclusion in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh: The Role of Religion." Indian Journal of Human Development 1.1 (2007): 69-101.

- ^ "Latest News @". Newkerala.com. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ "Bangladesh". State.gov. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ "Bangladesh - Population Census 1991". catalog.ihsn.org.

- ^ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Population

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nahid Kamal. "The Population Trajectories of Bangladesh and West Bengal During the Twentieth Century: A Comparative Study" (PDF).

- ^ http://203.112.218.65 › ImagePDF Web results Population and Housing Census 2011 - Bangladesh Bureau of ...

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/10/25/bangladesh-is-now-home-to-almost-1-million-rohingya-refugees/

- ^ https://www.foxnews.com/world/bangladesh-point-finger-at-myanmar-for-rohingya-genocide

- ^ https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/who-appeals-international-community-support-warns-grave-health-risks-rohingya

- ^ https://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/muslims/

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population & Housing Census 2011 (Zila Series & Community Series)" Check

|url=value (help). http. Retrieved 2021-07-23. See individual Zila files for religion and population information - ^ "History and archaeology: Bangladesh's most undervalued assets?". deutschenews24.de. 2012-12-21. Archived from the original on 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ^ Mahmood, Kajal Iftikhar Rashid (2012-10-19). সাড়ে তেরো শ বছর আগের মসজিদ [1350 Year-old Mosque]. Prothom Alo (in Bengali).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs.

- ^ "Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs.

- ^ "Current Legal Framework: Inheritance in Bangladesh". International Models Project on Women's Rights.

- ^ "Article 2A The State Religion". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs.

- ^ "Religion, Secularism Working in Tandem in Bangladesh". Gallup. 2009-07-29. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ Anis Ahmed (28 February 2013). "Bangladesh Islamist's death sentence sparks deadly riots". Reuters. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ Arun Devnath; Andrew MacAskill (1 March 2013). "Clashes Kill 35 in Bangladesh After Islamist Sentenced to Hang". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ Julfikar Ali Manik; Jim Yardley (1 March 2013). "Death Toll From Bangladesh Unrest Reaches 44". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

External links[]

- Eaton, Richard M. (1993). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20507-3.

- Karim, Abdul (2012). "Islam, Bengal". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Development Cooperation and Islamic values in Bangladesh

- US State Department [1]

- Islam in Bangladesh

- Islam by country