Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan

| Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581 | |

|---|---|

| Russian: Иван Грозный и сын его Иван 16 ноября 1581 года | |

| |

| Artist | Ilya Repin |

| Year | c. 1883–1885 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 199.5 cm × 254 cm (78.5 in × 100 in) |

| Location | Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow |

Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581[a] is a painting by Russian realist artist Ilya Repin made between 1883 and 1885. It depicts a grief-stricken Ivan the Terrible cradling his dying son, the Tsarevich Ivan Ivanovich, shortly after the elder Ivan had dealt a fatal blow to his son's head in a fit of anger. The painting portrays the anguish of remorse on the face of the elder Ivan and the gentleness of the dying Tsarevich forgiving his father with his tears.

The artist used Grigoriy Myasoyedov, his friend and fellow artist, as the model for Ivan the Terrible, with writer Vsevolod Garshin modelling for the Tsarevich. In 1885, upon completion of the oil on canvas work, Repin sold it to Pavel Tretyakov for display in his gallery.

The artwork has been called one of Russia's most famous and also one of its most controversial paintings. It has been vandalised twice, in 1913 and again in 2018. It remains on display in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Subject of the painting and historiography[]

The details of Tsarevich's death are unknown and are a matter of controversy. It occurred in 1581, in the Alexandrov Kremlin, the residence of Tsar Ivan the Terrible from 1564 to 1581, the centre of his oprichnina and de facto capital of the country.

In contemporary Russian chronicles and sources[]

In a letter addressed to Nikita Zakharin and Andrey Shchelkalov in 1581, the Tsar himself wrote that "he cannot go to Moscow because of his son's illness" without indicating what illness he suffered from.[1] Several contemporary Russian chronicles mention the Tsarevich's death without providing any details.[2] Only the Piskarevsk Chronicle adds that the death occurred at midnight. However, none of these chronicles suggests that the death of Ivan Ivanovich was violent.[3] Other sources provide a more detailed version of the death, claiming that the Tsarevich was mortally wounded by his father during an argument. One of these sources, the Mazurin chronicle, reports the following:[4]

In the summer of 7089, it was from the Sovereign Emperor and Grand Prince Ivan Vassilievitch, that his son, his greatness Prince Tsarevich Ivan Ivanovich, shining with wise meaning and grace and separated from the branch of life by a blade, received evil, and from this evil, he died.

They indicate that the event took place on 14 November 1581 and that the Tsarevich would have died on 19 November. However, the dates vary. The diary of the dyak (clerk) Ivan Timofeev mentions that "some say (of the Tsarevich) that his life was extinguished because of blows by the hands of his father, after trying to prevent him from committing an ugly act".[5]

Foreign testimonies[]

Contemporary foreign sources are more eloquent: Jacques Margeret, a French mercenary captain in service in Russia, writes that "there is a rumour that he (the tsar) killed the eldest (son) with his own hand, which wasn't the case, because, although he struck him with the end of the rod and he was wounded by a blow, he did not die from this, but some time later, on a pilgrimage journey".[6]

Another version is reported by the papal diplomat Antonio Possevino. According to him, in November 1581 in the Alexandrov Kremlin, Ivan the Terrible found his daughter-in-law Helen lying on a bench in undergarments.[b]

The third wife of Ivan's son was laying on a bench, dressed in underwear. She was pregnant and didn't expect anyone to visit her. However, the Grand Prince of Moscow (Ivan the Terrible) paid her an unexpected visit. She immediately stood up to meet him, but it was already impossible to calm him down. He hit her in the face, and then beat her with his staff, punching her so hard that she lost her child the next night.

His son Ivan then ran to his father and asked him not to beat his wife, but this only made his father angrier. The Prince started hitting his son with his staff, which resulted in a very serious wound in the head. Before that, in anger at his father, the son hotly reproached him in the following words:

"You imprisoned my first wife in a convent for no reason, you did the same with my second wife, and now you are beating up the third in order to kill the child she carries in her womb." Having injured his son, the father immediately indulged in deep grief and immediately summoned doctors and Andrei Shchelkalov and Nikita Romanovich from Moscow to have everything at hand. On the fifth day, the son died and was transferred to Moscow.

— Antonio Possevino, Historical writings about Russia in the 16th century[8]

Stories of Russian historians[]

18th-century Russian historian Nikolay Karamzin also believed that the Tsarevich died because of his father, but with different details and circumstances.[9]

He (Ivan the Terrible) put his hand on him (Tsarevich). Boris Godunov wanted to come to his aid but the Tsar inflicted several wounds to him with the point of his sceptre and struck the Tsarevich with it on the head. He then fell to the ground, spilling his blood. The father's fury disappeared. Paling with fear, trembling, in complete shock, he exclaimed "I killed my son" and he threw himself down to kiss him; pouring out the blood flowing from a deep wound, he wept, sobbed, called for the doctors. He implored the mercy of God and the forgiveness of his son

Ilya Repin relied on Karamzin's story to paint Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581, one of the most striking paintings of his chrestomathy.[10] Russian imperial historian Mikhail Shcherbatov, who studied the different versions of Ivan Ivanovich's death, considers Possevino's version the most plausible,[11] while the Russian imperial historian Vasily Klyuchevsky declared it the only reliable version.[12]

Background and inspiration[]

Repin began working on the painting in Moscow.[13] A first overall sketch, with the character of the Tsar turned to his right, dates from 1882. The idea of the painting, according to Repin himself, is linked to his confrontation with the themes of violence, revenge and blood during the political events of 1881, with additional sources of inspiration being the music of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and the bullfights he witnessed during a trip to Western Europe in 1883.

Political violence[]

On March 13, 1881, in Saint Petersburg, the Russian Tsar Alexander II of Russia was killed by a bomb thrown by Ignacy Hryniewiecki, a member of the revolutionary organization Narodnaya Volya. The bomb also seriously injured the terrorist, who died a few hours later. His accomplices, the Pervomartovtsy, were executed on April 13, 1881.[14][15]

Repin, who came to Saint Petersburg in mid-February 1881 for the opening of the Wanderers' exhibition, was there when the Tsar was killed. He returned there in April and attended the execution of the perpetrators and accomplices of the attack.[16]

Russian poet and friend of Repin, Vasily Kamensky, wrote in his memoirs that the painter had told him "how he had witnessed the public execution of the Pervomartovtsy: Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Mikhailov and Rysakov. "Ah, as it was nightmare times," - sighed Repin - "complex, appalling. I even remember each board on the breasts, with the inscription "regicide". I even remember Zhelyabov's gray pants, Perovskaya's black hat".[16]

Several of Repin's next paintings were devoted to Pervomatovsty: Refusal of confession ("Отказ от исповеди" (1881)), Arrest of a propagandist ("Арест пропагандиста" (1882)), Unexpected visitor ("Не ждали" 1884-1888)). He also returns several times in his memoirs on this period of his creations:[17][18]

This year followed like a trace of blood, our feelings were bruised by the horrors of the contemporary world, it was frightening to confront it: it will end badly! (...) We had to look for a way out at this key moment in history.

Thus, for Repin, there is a link between the events of 1881 and the scene represented in Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581 from exactly 300 years earlier, in which the tsar is the murderer.[16]

Music of Rimsky-Korsakov[]

Another inspiration for the painting was the "Antar" symphonic suite by the Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The suite is composed of four movements: the opening movement, vengeance, power and love.[19]

It is the music of Antar's bloody second movement, Vengeance,[20] that inspired Repin the most. He talks about this in his memoirs:[21][13]

In Moscow in 1881, while I was listening to a new piece by Rimsky-Korsakov, Vengeance ("Месть"). This sound wave took possession of me, and I thought, that I could not embody the state of the soul I had known under the influence of this music in a painting

I then remembered Tsar Ivan.

Trip to Europe[]

Repin's painting is also striking because of its representation of blood: the one seeping from the Tsarevich's temple and the blood puddle on the ground left there before his father picked him up. Such representations are uncommon in Russian art. The painter explains in his memoirs that he was influenced by his trip to Europe in 1883, where he witnessed bullfights:[18]

Misfortune, death, murder and blood make up a hole that draws you into it with force. At the same time, there are so many bloody paintings in all the exhibitions. And I, probably overtaken by all this bloodiness, on my return home, started the bloody scene of Ivan the Terrible with his son. And this painting had a great success.

Creation[]

According to Repin, the design and painting of the canvas were a long ordeal:[21]

I painted in tears, I was tortured, I tormented myself, I corrected again and again what I had painted, I hid it, in a sickly disappointment, no longer believing in my strength, I erased what I had painted. I had already erased, and I was attacking the canvas again. Every minute was terrible to me. I was disappointed with this painting, I hid it. And she made the same impression on my friends. But something pushed me towards her, and again I was working on it.

The room depicted in the painting is one of the rooms of the Chambers of the Romanov Boyars from the 17th century, while the accessories, throne, mirror, kaftan, were painted at the Kremlin Armoury. The chest is part of the collections of the Rumyantsev Museum.[13]

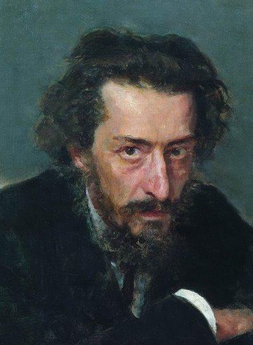

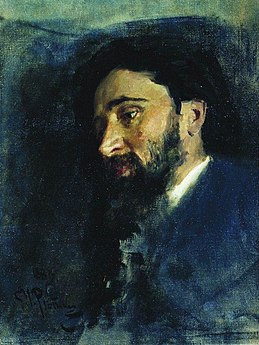

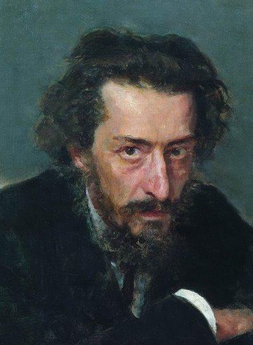

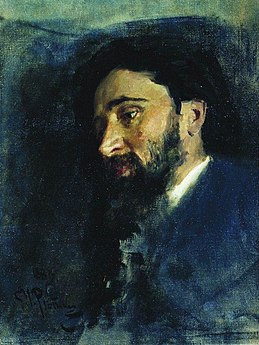

Repin worked the most on the choice of models by seeking the faces he needs from acquaintances or passers-by. The models for Ivan the Terrible were the painter Grigoriy Myasoyedov and the composer Pavel Blaramberg. While the landscape painter Vladimir Menk and writer Vsevolod Garshin modelled for Tsarevich Ivan Ivanovich.[18]

Asked about choosing Garshin, Repin replies:[22]

There is a predestination in Garshin's face that struck me. He has the face of a man irreparably condemned to perish. This is what was needed for my tsarevich.

- Sketches and portraits of the models

Portrait of composer Pavel Blaramberg (1884).

Portrait of the painter Grigoriy Myasoyedov (1883).

Portrait of the writer Vsevolod Garshin (1883).

Portrait of the painter Vladimir Menk (1884).

- Ivan the Terrible kills his son - detail

According to Polish-American art historian Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier, it is this incorporation of Garshin's face that completes and allows her to be fully satisfied with the painting.[23]

Analysis[]

Moment represented[]

- pencil sketch (1882 - 20.7 х 27.1 cm);

- oil sketch (1883, 1899 - 22.2 x 36 cm);

- table subject of the article (1884-1888).

Although the painting is sometimes called Ivan the Terrible kills his son, Repin does not paint the moment when the Tsar hits the Tsarevich. The work does not represent violence, but its resolution.[23] Ivan the Terrible picked up his son. His eyes "bulging with horror, despair and madness",[24] he embraces him by the waist. Tsarevich Ivan, weeping, gently waves his hand.[25]

Two modifications made to the preliminary sketches show the distance established by the painter with the altercation: the sceptre with which the Tsar struck his son's temple, is in his hand in the first sketches, while in the final painting, it is posed on the ground in front of them.[24][25] The bloodstain, where the Tsarevich's head rested on the ground, very visible in the oil sketch that Repin made in 1883, and which he kept and resumed later, is erased in the shadows of the final painting. Ivan Ivanovich's dress no longer has a long bloodstain. The moment represented becomes that of remorse, forgiveness and love.[25]

But the painting also shows, in its centre, the reality and the irreversibility of the act of the tsar: the blood flows from the temple of his son, and the attempt that Ivan the Terrible makes to contain it with his left hand is hopeless.[24]

Description and composition[]

The canvas is one of Repin's large canvases (199.5 × 254 cm). Its dimensions are comparable to the Barge Haulers on the Volga or to the Religious Procession in Kursk Governorate.[26]

The two characters, three quarters, are crisscrossed to each other in the centre of the painting. In a twilight light,[26] they stand out both from the foreground of the canvas and the background plunged into semi-darkness.[24][27] The gesture by which Ivan the Terrible hugs and supports his son's waist is reminiscent of two paintings by Dutch painter Rembrandt in the Hermitage Museum, The Return of the Prodigal Son and David and Jonathan, which Repin has studied and admired since his formative years.[25][16]

The construction of the painting is based on a few objects and pieces of furniture distributed around the characters: the crumpled red carpets on the floor, the Tsarevich's boots, the sceptre, the throne overturned during the argument, one of the ornamental balls which sparkles at the level of the son's eyes, and his cushion.[24] Behind, other pieces of furniture, such as the stove, the mirror of the Armor Museum or the chest of the Rumyantsev Palace, are less discernible. The back wall of the room is partly covered with a red and black diamond pattern. At the top, on the left, is a narrow bay.[13]

Colours and material[]

Repin wrote that he refused "the acrobatics of the brush and painting for the sake of painting"[28] and that "the beauty, the touch or the virtuosity of the brush" was not the only important thing, and that he had always pursued "the essential: the body, as a body".[29] Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan is nonetheless "painted with such a diversity of craftsmanship and with such a rich palette of dark chords" that it is, according to Russian painter and art critic Ivan Kramskoi, an "authentic orchestra".[26] An "intense red"[30] or "blood red",[31] and "thick and saturated crimson red" predominates.[26] It is painted with pure colour, without any additions, and then reworked by the painter with an extraordinary diversity of shades.[30]

The scarlet red of the blood flowing from the wound on the Tsarevich's temple stands out, or the reflections on the folds of his kaftan, or finally the dark red puddle of blood on the red carpet, and this tension of colours resonates with the tragedy depicted on the canvas.[30] In the centre, the magnificence of the tsarevich's kaftan contrasts with the darkness of Ivan the Terrible's black coat.[31]

The painter breaks this combination of blood red, pink and dark brown tones with the complementary tones of the green of the Tsarevich's boots and the deep blue of his velvet trousers.[31] The white light, "cold and weak", which penetrates through a narrow bay, attenuates this tension of colours and further reinforces the dramatic tension of the scene.[30]

Symbolic scope[]

The writer's first work, it exhibits the interior monologue of a soldier wounded and left for dead on the battlefield for four days, face to face with the corpse of a Turkish soldier he has just killed. His deep empathy for all beings is already there.

For his contemporaries, and undoubtedly for Repin himself, the first symbolic function of the painting is to express the existence of violence and the moral rejection, which must be the object. Ivan Kramskoi gives this formulation: "it seems that a human being, after having carefully looked at this painting, even if only once, will be forever protected from the wild beast he has, as they say, in him".[18]

With the way they are represented, the aftermath of the father's altercation with his son is not just a historical episode, they illustrate a man's "eternal" capacity to put a hand or sword on his neighbour. The painting can thus be understood as a pictorial parable of the phrase "you shall not kill".[18][26]

Aside from promoting a moral law, the picture also seemed to slide towards a more particularly religious inspiration, showing that "Christian love and forgiveness" can repair crime, even infanticide.[25] The tsarevich's gesture, his face, "almost like that of an icon," the tear which runs down the wing of his nose, seem to depict forgiveness.[24] The similarity, already mentioned above, of the gesture of the right arm of Ivan the Terrible with the two Rembrandt paintings also aligns with this position.[25]

In the interpretation of the work, the personality of the writer Vsevolod Garshin, mentioned several times, provides additional details. Repin takes him as a model in this period in several paintings: Ivan the Terrible and his son and his preparatory sketches, but also a Portrait painted in 1884, and the large painting Unexpected Visitor, which he poses for the main character. Unexpected Visitor began in 1884 and ended the year of Garshin's suicide in 1888.[25]

Vsevolod Garshin was appreciated by Repin, who considered him an "incarnation of the divine" during their friendship and after his death. He wrote that "his pensive eyes, often mixed with tears provoked by some injustice, his humble and delicate attitude, his angelic personality, with the purity of a dove, were those of a God". More than Garshin's physical features, it is therefore also his personality and his deeply peaceful thought that Repin's painting refers to.[25]

A representation of power[]

There remains the question of the political significance of the painting, which cannot be eluded, if only because of the reactions to which it was immediately the subject. Painting a murderous and infanticide tsar, just after the assassination of Alexander II, cannot be accidental, and Repin, as indicated above, combines the two events. The painter does not express himself more on this point, and neither does Russian criticism.[16]

On the other hand, French critics approach it. For Alain Besançon, the tsarevich's self-immolation by the tsar is a central scene of the Russian myth, which Repin was the first to represent: the history of Russia would be built on the sacrifice of sons killed by their fathers.[32]

Pierre Gonneau supports a converging position, stressing that this sacrificial vision refers "to the symbolic roots of the monarchy because the sacrificed tsarevich finds himself in a position to embody the forces opposing the authority of the tsar". It makes a link with the trial of Tsarevich Alexis, son of Peter the Great, and his death as a result of the tortures he suffered. This other conflict between a father and his son is the theme of an 1871 painting by Nikolai Ge, Peter the Great interrogates Tsarevich Alexis in Peterhof.[33]

1909 version[]

In 1909, on a commission from the industrialist and collector Stepan Ryabushinsky, Repin painted a second version of Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan, which he called Infanticide (Сыноубийца). It is on display at the Voronezh Museum of Fine Arts.[10] The second version is separated by 25 years from the first. In this version, Repin added a character of a woman in the background and unveiled more colours than in the original painting, in a more “luxuriant” direction, while Tsar Ivan's face has collapsed in grief.[34]

Infanticide (1909).

Detail of Infanticide.

Reception and imperial censorship[]

The canvas was shown for the first time in 1885 to Repin's painter friends, among whom were Ivan Kramskoi, Ivan Shishkin, Nikolai Yaroshenko, Pavel Brullov and others; According to Repin, his hosts were stunned and silent for a long time, waiting to see what Kramskoi would say.[35]

I was seized with a feeling of complete appreciation for Repin. There it is, the thing, what a level of talent ... And how it's painted, my God, how it's painted! ... And what is this murder, carried out by a wild beast and a psychopath? ... A father hits his son with his sceptre in the temple? One moment ... He utters a cry of terror ... He grabs him, he sits him on the ground, he raises him ... He presses one of his hands on the wound in the temple (and blood gushes out of the cracks between the fingers) ... and as he bawls ... It's an animal, howling with fear ... the very spot that the son has marked with his temple ... Really, this scene is drowning us in half-light and a kind of natural tragic.

The very conservative Attorney General of the Holy Synod, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, tells Alexander III of his "repulsion" and perplexity.[33] The painting did not please the emperor and his entourage, and it was forbidden to show it on April 1, 1885. It was the first painting to be censored in the Russian Empire,[35] and Pavel Tretyakov, who bought it, was told to "not to expose it, and more generally not to allow it to be brought to the attention of the public by any other means". The ban was lifted after three months, on July 11, 1885, after the intervention of the painter Alexey Bogolyubov.[18][35]

Vandalism and controversies[]

On January 16, 1913, Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan on November 16, 1581 was slashed with three stab wounds, carried by a 29-year-old iconoclast, son of the great furniture maker Abram Balachov. The curator of the Tretyakov gallery, Georgy Khruslov, learning of the deterioration of the canvas, threw himself under a train.[36] The painting was practically restored to its original state, with the help of Ilya Repin.[35]

Some Russian nationalists continue to protest the painting's exhibition as they believe it was actually part of a foreign smear campaign and the scene depicted is inaccurate.[37]

In October 2013, a group of Orthodox historians and activists, led by the apologist and supporter of the canonization of Tsar Ivan, Vassili Boiko-Veliki, addressed the Minister of Culture of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Medinsky, to ask him to remove the canvas from the Tretyakov Gallery, on the grounds that it would offend the patriotic feelings of the Russians.[38][37] The director of the Tretyakov Gallery, Irina Lebedeva, formally opposed it.[37]

In May 2018, the canvas was again attacked in the Tretyakov Gallery by a drunk visitor who broke its protective glass with a metal bar. The painting suffered serious damage. The canvas was pierced in three places in the central part of the work, which depicts the figure of the tsarevich. The frame was also badly damaged, the gallery said, but that "by a happy coincidence" the most precious elements of the painting – the depiction of the faces and hands of the tsar and his son – were not damaged. Some Russian media cited him as saying he had attacked the painting because he thought the depiction was inaccurate.[37] The attacker was imprisoned for two and a half years in prison.[39]

Legacy[]

Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan remains one of Russia's most famous and the most psychologically intense of Repin's paintings.[40]

The work appears briefly in the third episode of the 2019 HBO miniseries Chernobyl.[41]

See also[]

Notes and references[]

Notes[]

- ^ The work is variously referred to as Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan, with or without the date, or Ivan the Terrible Kills His Son.

- ^ The female dress of this period usually consisted of two undergarments, the bottom, the shirt, and the top, the dress. The shirt was a garment for domestic use, and it was considered very improper to appear to strangers in it, especially in front of men.[7]

References[]

- ^ Likhachyov, Nikolay (1903). Дело о приезде в Москву А. Поссевино [The case of A. Possevino's arrival in Moscow] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg. p. 58.

- ^ "Московский летописец" [Moscow chronicle]. Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles (in Russian). 34. Moscow. 1978. p. 228. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Пискаревский летописец" [Piskarevsky chronicle]. Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles (in Russian). 34. Moscow. 1978. p. 195. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Мазуринский летописец" [Mazurin chronicle]. Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles (in Russian). 31. Moscow. 1978. p. 142. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Timofeev Ivan (1951). Временник Ивана Тимофеева [Annals of Ivan Timofeev]. Publishing house of the USSR Academy of Sciences. p. 182.

- ^ Jacques, Margeret; Nikolaevich, Ilya (1986). Состояние Российской империи и Великого княжества Московского [State of the Russian State and the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1606] (in Russian). Leningrad. p. 232.

- ^ Zabelin Ivan (1901). Домашний быт русских цариц в XVI-XVII столетиях [Household life of Russian queens in the XVI-XVII centuries] (in Russian). Moscow. p. 515. ISBN 978-5-373-07405-6.

- ^ Possevino, Antonio (1983). Исторические сочинения о России XVI в [Historical writings about Russia in the 16th century] (in Russian). Moscow: Moscow University Publishing House. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Karamzin, Nikolay. "9". Продолжение царстования Иоанна Грозного. Г. 1577-1582 [Continuation of the reign of Ivan the Terrible. 1577-1582]. History of the Russian State (in Russian). 9.

- ^ a b Yudenkova, Tatyana (2019). ""I love variety..." ILYA REPIN'S INDEFATIGABLE NOVELTY ACROSS TIME AND GENRE". tretyakovgallerymagazine.com. Tretyakov Gallery. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Shcherbatov, Mikhail (1789). "3" (PDF). История Российская с древнейших времен. 5. pp. 120–126. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Klyuchevsky, Vasily. Курс русской истории [A History of Russia] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg.

- ^ a b c d "История создания картины Репина "Иван Грозный и сын его Ива"". ilya-repin.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Kel'ner 2015.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 279.

- ^ a b c d e Lyaskovskaya, Olga (1953). "К истории создания картины И. Е. Репина «Иван Грозный и сын его Иван 16 ноября 1581 года»". Илья Ефимович Репин [Ilya Yefimovich Repin] (in Russian). Moscow. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Alexandrova, Natalya; Nikonova, Natalya; Vvedenskaya, Elena (2010). Герои и злодеи русской истории в искусстве XVIII — XX веков [Heroes and criminals in the history of Russian art from the 18th to the 20th century] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg. p. 95. ISBN 978-5-93332-355-6.

- ^ a b c d e f "Илья Репин. Галерея картин и рисунков художника - Иван Грозный и сын его Иван 16 ноября 1581 года, 1885" [Ilya Repin. Gallery of paintings and drawings of the artist - Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan November 16, 1581, 1885]. ilya-repin.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Rakhmanova, Marina. "Римский-Корсаков. "Антар" (Antar, Op. 9)" [Rimsky-Korsakov. "Antar" (Antar, Op. 9)]. belcanto.ru. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Vasiliev-Sedoy, Victor. "Репин. Реальность, парадоксы и мистика" [Repin. Reality, paradoxes and mysticism]. proza.ru. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b Nadezhda, Ionina (2000). Сто великих картин [Hundred great paintings] (in Russian). Moscow: Вече. ISBN 5-7838-0579-3.

- ^ Prorokova, Sophia (1960). Репин [Repin] (in Russian). Moscow: Молодая гвардия. p. 209.

- ^ a b Valkenier, Elizabeth (1993). "The Writer as Artist's Model: Repin's Portrait of Garshin" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum Journal. 28: 212. doi:10.2307/1512927. JSTOR 1512927. S2CID 155366014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Esaoulova, Alena. "Илья Ефимович Репин - «Иван Грозный и его сын Иван 16 ноября 1581 года»". arthive.com. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Valkenier, Elizabeth (1993). "The Writer as Artist's Model: Repin's Portrait of Garshin" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum Journal. 28: 211. doi:10.2307/1512927. JSTOR 1512927. S2CID 155366014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Churak, Galinina (2014). Илья Репин [Ilya Repin] (in Russian). Tretyakov Gallery. p. 35. ISBN 9785894800325. OCLC 49657097. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Fetzer, Leland (1975). "Art and Assassination: Garshin's 'Nadezhda Nikolaevna'". The Russian Review. 34 (1): 55–65. doi:10.2307/127759. JSTOR 127759.

- ^ Chukovsky, Korney (1969). Илья Репин [Ilya Repin] (in Russian). Moscow. p. 59.

- ^ Repin, Ilya (1937). Далёкое близкое [Distant close] (in Russian). Moscow: Захаров. p. 351. ISBN 5-8159-0204-7.

- ^ a b c d Nadezhda, Ionina. "Репин И. Иван Грозный убивает своего сына" [Ivan the Terrible kills his son]. ikleiner.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Н.Д. Моргунова-Рудницкая. "И.E. Репин - Иван Грозный и сын его Иван 16 ноября 1581 года". nearyou.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Poirson-Dechon, Marion (2016). "Du sacrifice d'Isaac au tsarévitch immolé" [From the sacrifice of Isaac to the slain tsarevich] (PDF). tramayfondo.com (in French). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b Gonneau, Pierre (2014). "Comment s'est forgée l'image d'Ivan le Terrible" [How the image of Ivan the Terrible was forged]. lejournal.cnrs.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Gnezdilova, Olga (5 August 2017). "Как Илья Репин изменил картину об Иване Грозном через 25 лет после ее создания" [How Ilya Repin changed the painting about Ivan the Terrible 25 years after its creation]. umbra.media (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Илья Репин. Иван Грозный и сын его Иван 16 ноября 1581" [Ilya Repin. Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan on 16 November 1581]. tanais.info (in Russian). Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Troitsky, Nikolay. "Культура: Искусство // Россия в XIX веке: Курс лекций" [Culture: Art // Russia in the XIX century: Course of lectures]. scepsis.net (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bodner, Matthew (27 May 2018). "Ivan the Terrible painting 'seriously damaged' in pole attack". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Православные активисты требуют убрать из Третьяковки картьяковки картину Репина" [Orthodox activists demand that Repin's painting be removed from the Tretyakov Gallery]. echo.msk.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Russian Sentenced For Vandalizing Iconic Painting Of Ivan The Terrible". rferl.org. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "'Ivan the Terrible' Painting Damaged in Russia in Vodka-Fueled Attack". nytimes.com. New York Times. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Chernobyl". artpapers.org. Art Papers. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2016). Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691638546.

- Kel'ner, Viktor Efimovich (2015). 1 marta 1881 goda: Kazn imperatora Aleksandra II (1 марта 1881 года: Казнь императора Александра II). Lenizdat. ISBN 978-5-289-01024-7.

External links[]

- Ольга Лясковская (Olga Lyaskovskaya). "К истории создания картины И. Е. Репина «Иван Грозный и сын его Иван 16 ноября 1581 года»" [On the history of the painting by I.E. Repin "Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581"]. cont.ws (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- Алена Эсаулова (Alena Esaulova). "Илья Ефимович Репин - «Иван Грозный и его сын Иван 16 ноября 1581 года»" [Ilya Efimovich Repin - "Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581"] (in Russian). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- 1885 paintings

- Cultural depictions of Ivan the Terrible

- Paintings by Ilya Repin

- Collections of the Tretyakov Gallery

- History paintings

- Paintings about death

- Vandalized works of art in Russia