Kaftan

A kaftan or caftan (/ˈkæftæn/; Persian: خفتان khaftān) is a variant of the robe or tunic, and has been worn in a number of cultures around the world for thousands of years and is of Asiatic origin. In Russian usage, kaftan instead refers to a style of men's long suit with tight sleeves. Used by many West and Southwest Asian ethnic groups, the kaftan is ancient Mesopotamian (modern day Iraq) in origin. It may be made of wool, cashmere, silk, or cotton, and may be worn with a sash. Popular during the time of the Ottoman Empire, detailed and elaborately designed garments were given to ambassadors and other important guests at the Topkapi Palace. Variations of the kaftan were inherited by cultures throughout Asia and were worn by individuals in Russia (North Asia, Eastern Europe and formerly Central Asia), Southwest Asia and Northern Africa [1] Styles, uses, and names for the kaftan vary from culture to culture. The kaftan is often worn as a coat or as an overdress, usually having long sleeves and reaching to the ankles. In regions with a warm climate, it is worn as a light-weight, loose-fitting garment. In some cultures, the kaftan has served as a symbol of royalty.

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

History[]

According to Encyclopedia of Islam, this fashion came up quite early among Arabs under the influence of Persian fashions. In Arabic, the word khaftān is used just like in Persian. It is described as a long robe as far as the calves sometimes or just under the knee. It is open at the front and the sleeves are slight cut at the wrists or even as far as to the middle of the arms.

D'Arvieux in his travels in the 17th century mentions Syrian Amirs and Bedouin Sheikhs wearing the Kaftan as winter garments.[2]

Abbasid era[]

During the Islamic golden age of the Abbasid era, the cosmopolitan super-culture spread far and wide to Chinese emperors, Anglo-Saxon coinage, but also in Constantinople too (current day Istanbul). They were mimicking and imitating Baghdadi culture (capital of the Abbasids).

Even Theophilus who fought the Arabs in the 830's on the battlefield built a Baghdad-style palace near the Bosporus. They went about a l'arabe in kaftans and turbans. Even as far as in the normal streets of Ghuangzhou during the era of Tang, the Persian kaftan was in fashion.[3]

It became a luxurious fashion, a richly styled robe with buttons down the front. The caliphs wore elegant kaftans made from silver or gold brocade and buttons in the front of the sleeves.[4] The caliph al-Muqtaddir (r. 908-932) wore a kaftan from silver brocade Tustari silk and his son one made from Byzantine silk richly decorated or ornamented with figures. The kaftan was spread far and wide by the Abbasids and made known throughout the Arab world.[5]

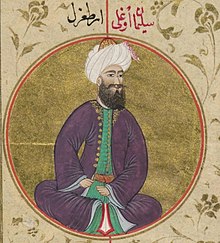

Turkish Kaftan[]

The kaftan was the favourite garment worn in Turkish states of Central Asia, the Turkish Empire in India, the Seljuk Turks and the Ottomans.[6] It was the most important component of the Seljuk period and it’s has been traced as far back to the tombs of the Huns.[7] The Seljuk Sultan Ahmad Sanjar who ruled from 1097-1118 gave 1000 red kaftans to his soldiers.[8] Also during the times of the Seljuk Sultan Malik Shah the Seljuk Turks wore kaftans and excavations discovered a child’s kaftan dating back to the reign of Sanjar-Shah who ruled from 1185 or 1186 to 1187.[9][10]

The tiles in the Kubadabad Palace depict Turkish figures dressed in kaftans.[11] The palace was built for Sultan Aladdin Kayqubad I who ruled from 1220-1237. Furthermore, typical Seljuk depictions from the 11th to the 13th century depict figures dressed in Turkish style caftans.[12] The kaftan was also worn by the Anatolian Seljuks who had even gifted kaftans to the first Ottoman Sultan, Osman I.[13][14] In connection with the inheritance of Osman I, the historian Neşri described a kaftan in the list of inherited items: “There was a short-sleeved kaftan of Denizli cloth.”[15] In an excavation in Kinet in Turkey, a bowl dating back to the early 14th century was found with a depiction of a man wearing what appears to be a Kaftan.[16]

Kaftans were worn by the sultans of the Ottoman Empire. Decoration on the garment, including colours, patterns, ribbons, and buttons, indicated the rank of the person who wore it. From the 14th century through the 17th century, textiles with large patterns were used. By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, decorative patterns on the fabrics had become smaller and brighter. By the second half of the 17th century, the most precious kaftans were those with 'yollu': vertical stripes with varying embroidery and small patterns – the so-called "Selimiye" fabrics.[citation needed]

Most fabrics manufactured in Turkey were made in Istanbul and Bursa, but some textiles came from as far away as Venice, Genoa, Persia (Iran), India, and even China. Kaftans were made from velvet, aba, bürümcük (a type of crepe with a silk warp and cotton weft), canfes, çatma (a heavy silk brocade), gezi, diba (Persian: دیبا), hatayi, kutnu, kemha, seraser (Persian سراسر) (brocade fabric with silk warp and gold or silver metallic thread weft), serenk, zerbaft (Persian زربافت), and tafta (Persian تافته). Favoured colours were indigo blue, kermes red, violet, pişmiş ayva or "cooked quince", and weld yellow.[citation needed]

Algerian Kaftans[]

The Female Kaftan is inscribed in the intangible cultural heritage of humanity, as Tlemcen's costume. It is the main piece of the Chedda of Tlemcen.

The kaftan has been historically documented to be worn in Algeria since the beginning of the 16th century. Following the Ottoman tradition, the male Kaftan, known as the Kaftan of honour, was bestowed by the Ottoman Sultan upon the governors of Algiers who, in turn, bestowed caftans upon the Beys and members of distinguished families.[17][18] In his Topography and General History of Algiers, described it as a coloured robe made of satin, of damask, of velvet and silk and having a form that reminded him of the priests' cassocks.[19] The Dey wore the Kaftan with dangling sleeves; the khodjas (secretaries) wore a very long cloth based Kaftan, falling to the ankles; the chaouchs (executors of the justice of the dey) were recognized by a green Kaftan with sleeves either open or closed, according to their rank. The Kaftan was also worn by the janissaries in the 17th and part of the 18th century.[19] It continued to be worn by male dignitaries well into the 20th century.[19]

The female Kaftan, on the other hand, evolved locally and derives from the ghlila,[20] a mid-calf jacket that combined Morisco and Ottoman influences, but which evolved following a very specific Algerian style from the sixteenth century onward.[21] Between the sixteenth and seventeenth century, middle class women started wearing the ghlila. The use of brocades and quality velvet, the profusion of embroidery and gold threading were not enough to satisfy the need for distinction of the wealthiest Algerians who choose to lengthen the ghlila all the way to the ankles to make a Kaftan that became the centrepiece of the ceremonial costume, while the ghlila was confined to the role of daily clothing.[20]

In 1789, the diplomat Venture de Paradis described the woman of Algiers as follows:

When they go to a party, they put three or four ankle length golden kaftans on top of one another, which, with their other adjustments and gilding, may weigh more than fifty to sixty pounds. These kaftans in velvet, satin or other silks are embroidered in gold or silver thread on the shoulders and on the front, and they have up to the waistband big buttons in gold or silver thread on both sides; they are closed in front by two buttons only.

— Venture de Paradis, [20]

Several types of Kaftans were developed since then, while still respecting the original pattern. Nowadays, the Algerian female Kaftans, including the modernised versions, are seen as an essential garment in the bride's trousseau in cities such as Algiers, Annaba, Bejaia, Blida, Constantine, Miliana, Nedroma and Tlemcen.[22]

Moroccan Kaftan[]

According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the Kaftan was introduced into the Barbary States by the Ottomans and spread by fashion as far as Morocco.[2]

According to , the Caftan might have been introduced to Morocco by the Saadi king Abd al-Malik who had lived in Algiers and Istanbul. Worn by the dignitaries and women of the palace at first, it became fashionable among the middle classes from the late 17th century.[23][24]

According to Rachida Alaoui, the caftan dates back to the end of the 15th century[contradictory] in Morocco thanks to the area's Moorish history, representing, in part, a medieval Andalusian heritage. However, the first written record of the garment being worn in Morocco is from the 16th century, she states.[25][unreliable source?]

Today in Morocco, kaftans are mostly worn by women and the word kaftan in Morocco is commonly used to mean "one-piece dress". Alternative two-piece versions of Moroccan kaftans are called Takchita and worn with a large belt. The Takchita is also known as Mansouria which derives from the name of Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur[26] who invented Al-Mansouria and the new fashion of wearing a two-piece Kaftan.[26]

West African Kaftan[]

In West Africa, a kaftan is a pullover robe, worn by both men and women. The women's robe is called a kaftan, and the men's garment is referred to as a Senegalese kaftan.

A Senegalese kaftan is a pullover men's robe with long bell-like sleeves. In the Wolof language, this robe is called a mbubb and in French, it is called a boubou. The Senegalese kaftan is an ankle-length garment, and is worn with matching drawstring pants called tubay. Usually made of cotton brocade, lace, or synthetic fabrics, these robes are common throughout West Africa. A kaftan and matching pants are called a kaftan suit. The kaftan suit is worn with a kufi cap.[27] Senegalese kaftans are formal wear in all West African countries.

Persian[]

Persian kaftan robes of honour were commonly known as khalat or kelat.[28]

Russian (North Asia and Eastern Europe)[]

In Russia, the word "kaftan" is used for another type of clothing: a style of men's long suit with tight sleeves. Going back to the people of various Baltic, Turkic, Varangian (Vikings) and Iranic (Scythian) tribes who inhabited today's Russia along with the Slavic population, kaftan-like clothing was already prevalent in ancient times in regions where later the Rus' Khaganate and Kievan Rus' states appeared.

The Russian kaftan was probably influenced by Persian and/or Turkic people in Old Russia.[29] The word "kaftan" was adopted from the Tatar language, which in turn borrowed the word from Persia.[30] In the 13th Century, the kaftan was still common in Russia. In the 19th century, Russian kaftans were the most widespread type of outer-clothing amongst peasants and merchants in Old Russia. Currently in the early 21st Century, they are most commonly used as ritual religious clothing by conservative Old Believers, in Russian fashion (Rusfashion), Russian folk dress and with regards to Russian folklore.[31]

Jewish[]

Hasidic Jewish culture adapted a silky robe (bekishe) or frock coat (kapoteh, Yiddish word kapote or Turkish synonym chalat) from the garb of Slavic nobility (Polish nobility),[32] which was itself a type of kaftan. The term kapoteh may originate from the Spanish capote or possibly from "kaftan" via Ladino. Sephardic Jews from Muslim countries wore a kaftan similar to those of their neighbours.[citation needed]

Southeast Asian[]

In Southeast Asia, the kaftan was originally worn by Arab traders, as seen in early lithographs and photographs from the region. Religious communities that formed as Islam became established later adopted this style of dress as a distinguishing feature, under a variety of names deriving from Arabic and Persian such as "jubah", a robe, and "cadar", a veil or chador.[33]

In Western countries[]

In the recent era the kaftan was introduced to the West in the 1890s, Queen Victoria’s granddaughter Alix of Hesse wore a traditional Russian coronation dress before a crowd which included Western on-lookers, this traditional dress featured the loose-fitting Russian kaftan which was so exotic to Western eyes.[34] This was one of the first times a Western woman, a high-status Western woman who had also been seen in fashionable Western dress no less, was seen wearing something so exotic. The traditional Russian kaftan resembles the kaftans worn by the Ottoman sultans; it was in stark contrast to the tight-fitting, corseted dresses common in England at that time.

The kaftan slowly gained popularity as an exotic form of loose-fitting clothing. French fashion designer Paul Poiret further popularised this style in the early 20th century.

In the 1950s, fashion designers such as Christian Dior and Balenciaga adopted the kaftan as a loose evening gown or robe in their collections.[35] These variations were usually sashless.

American hippie fashions of the late 1960s and the 1970s often drew inspiration from ethnic styles, including kaftans. These styles were brought to the United States by people who journeyed the so-called "hippie trail".[35] African-styled, kaftan-like dashikis were popular, especially among African-Americans. Street styles were appropriated by fashion designers, who marketed lavish kaftans as hostess gowns for casual at-home entertaining.

Diana Vreeland, Babe Paley, and Barbara Hutton all helped popularise the caftan in mainstream western fashion.[36] Into the 1970s, Elizabeth Taylor often wore kaftans designed by Thea Porter. In 1975, for her second wedding to Richard Burton she wore a kaftan designed by Gina Fratini.[37]

More recently, in 2011 Jessica Simpson was photographed wearing kaftans during her pregnancy.[34] American fashion editor André Leon Talley has also worn kaftans designed by Ralph Rucci as one of his signature looks.[38] Beyoncé, Uma Thurman, Susan Sarandon, Kate Moss, Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen, and Nicole Richie have all been seen wearing the style.[39] Some fashion lines have dedicated collections to the kaftan, one example being the 2015 Summer Collection.[40]

For forward thinking fashion brands, Kaftans have been included as part of summer season lines for noted labels such as Roberto Cavalli, House Of Inoa Fashion and TheSwankStore which in turn has seen the kaftan dress gain popularity as a womenswear staple for those visiting tropical holiday destinations. Often made from silk & finished with crystals & beading embellishments on the neckline & back of the garments, the many and varied kaftan styles are often referred to as modern, luxury resortwear, with the term 'kaftans' making up a generic name, encompassing the style genre. Normally made with bright, colourful & unique print designs referencing traditional West, Southwest and South Asian cultures fused with on trend colour palettes & styles, these modern colourful outfits have begun to transcend use as resort only fashion items but as occasion wear items or as day to day wear.

Gallery[]

The first Mughal Emperor Babur dressed in a kaftan.

August III the Saxon in żupan, by Louis de Silvestre.

Evreu cu caftan (Jew in kaftan) by Nicolae Grigorescu.

An Armenian youth 'out of Persia' who wears a pale blue kaftan. Ottoman Turkish Illustrations from Peter Mundy's Album, Istanbul 1618.

Portrait of the artist's wife, Marie Fargues, in a kaftan, by Jean-Étienne Liotard.

21st century woman wearing kaftan, Spain.

Tzar Feodor I wearing a kaftan. Antiquities of the Russian country 1846-1853, Solntsev, Fedor Grigorievich.

Streltsy (warriors in Russia from 16th to the early 18th centuries) wearing kaftans. Painted in 19th century.

See also[]

- Chapan

- Deel (clothing)

- Kanzu

- Kufi

- Ottoman clothing

- Takchita

- Thawb

- Wrapper (clothing)

References[]

- ^ https://www.amanis.com/the-history-of-the-kaftan/

- ^ Jump up to: a b Huart, Cl. (24 Apr 2012). "Ḳaftān". doi:10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_SIM_3796. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Mackintosh-Smith, Tim (2019-04-30). Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes and Empires. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18235-4.

- ^ Cosman, Madeleine Pelner; Jones, Linda Gale (2009). Handbook to Life in the Medieval World, 3-Volume Set. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0907-7.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila S.; Blair, Sheila (2009-05-14). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^ Âletler ve âdetler Şevket Rado Ak Yayınları,

- ^ Cultural atlas of the Turkish world Türk Kültürüne Hizmet Vakfı Türk Kültürüne Hizmet Vakfı, 1997

- ^ Selçuk-nâme, Volume 2 Ahmed bin Mahmud (Bursalı) Tercüman Gazetesi,

- ^ An Universal History: From the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time, Volume 4 C. Bathurst, 1759

- ^ https://amp.ww.en.freejournal.org/15558887/1/sanjar-shah.html

- ^ Selçuk, Issue 3. Selçuklu Araştırmaları Merkezi,

- ^ Journal of Seljuk studies, Volume 3. P.101. Selçuklu Tarih ve Medeniyeti Enstitüsü.

- ^ The Anatolian Civilisations: Seljuk Ferit Edgü Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 1983

- ^ Dressed to Rule: Royal and Court Costume from Louis XIV to Elizabeth II Philip Mansel Yale University Press,

- ^ XIV-XVI centuries Tahsin Öz Turkish Press, Broadcasting and Tourist Department,

- ^ Mechanisms of Exchange: Transmission in Medieval Art and Architecture of the Mediterranean, ca. 1000-1500 BRILL, 15 Apr 2013

- ^ Chems-Eddine Chitour (2004). Algérie: le passé revisité : une brève histoire de l'Algérie. Casbah Editions. p. 221.

- ^ Jean-Michel Venture de Paradis (2006). Alger au XVIII siècle, 1788-1790: mémoires, notes et observations d'un dipolomate-espion. Éditions grand-Alger livres. p. 146.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Georges Marçais (1930). Le Costume musulman d'Alger. Plon. pp. 36–47.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Isabelle Paresys (26 February 2008). Paraître et apparences en Europe occidentale du Moyen Âge à nos jours. Presses Univ. Septentrion. p. 236. ISBN 978-2-85939-996-2.

- ^ Tara Zanardi; Lynda Klich (4 July 2018). Visual Typologies from the Early Modern to the Contemporary: Local Contexts and Global Practices. Taylor & Francis. p. 569. ISBN 978-1-315-51511-3.

- ^ "Tradition vestimentaire : Le Kaftan est Algérien". elmoudjahid.com (in French).

- ^ "Kaftan". museumwnf.org.

- ^ Algerians in Tetouan|الجزائريون في تطوان,p 127

- ^ "Rachida Alaoui, de l'origine du caftan". femmesdumaroc (in French). Retrieved 2020-06-04.

Il remonte à la fin du XVème siècle, et les premières mentions de ce vêtement porté par les Marocains datent du XVIème siècle." English:"It dates back to the end of the 15th century, and the first mentions of this garment worn by Moroccans date from the 16th century.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morocco in the era of the Saadi Dynasty|المغرب في عهد السعديين,p 305

- ^ Cicero, Providence (2009-02-27). "Afrikando Afrikando Dishes up Great Food with a Side of Quirkiness". The Seattle Times.

- ^ "CLOTHING xxvii. lexicon of Persian clothing – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- ^ Identity Formation and Diversity in the Early Medieval Baltic and Beyond : Communicators and Communication. Callmer, Johan,, Gustin, Ingrid,, Roslund, Mats. Leiden. 2017. pp. 91–102. ISBN 9789004292178. OCLC 951955747.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Richard Hellie (15 June 1999). The Economy and Material Culture of Russia, 1600–1725. University of Chicago Press. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-226-32649-8.

- ^ Wolff, Norma H. "Caftan". LoveToKnow. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- ^ http://www.jhi.pl/psj/chalat

- ^ Maxwell, Robyn (2003). Textiles of Southeast Asia: Trade, Tradition and Transformation. Periplus Editions. p. 310. ISBN 978-0794601041.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hix, Lisa (17 July 2014). "Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free". Collectors Weekly. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Annette Lynch; Mitchell D. Strauss (30 October 2014). Ethnic Dress in the United States: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-7591-2150-8.

- ^ Erika Stalder (1 May 2008). Fashion 101: A Crash Course in Clothing. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-547-94693-1.

- ^ Salamone, Gina (2 December 2011). "Elizabeth Taylor's prized possessions—ranging from diamonds to designer gowns—on view at Christie's before going on auction". NY Daily News. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Smith, Ray A. (9 October 2013). "An Emperor of Fashion". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Caftan Liberation: How an Ancient Fashion Set Modern Women Free". Collectors Weekly.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2015-09-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links[]

Media related to Kaftans at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kaftans at Wikimedia Commons

- Arab culture

- Arabic clothing

- History of Asian clothing

- Kurdish clothing

- Mesopotamia

- Moroccan clothing

- Ottoman clothing

- Robes and cloaks

- Russian folk clothing

- Uzbekistani culture