Ablaq

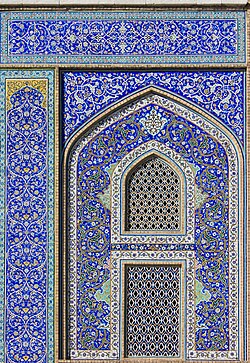

Ablaq (Arabic: أبلق; particolored; literally 'piebald'[1]) is an architectural technique involving alternating or fluctuating rows of light and dark stone.[2][3] Records trace the beginnings of this type of masonry technique to the southern parts of Syria.[4] It is associated as an Arabic term,[5] especially as related to Arabic Islamic architectural decoration.[6] The first recorded use of the term ablaq pertained to repairs of the Great Mosque of Damascus in 1109,[4] but the technique itself was used much earlier.[7]

Technique[]

This technique is a feature of Islamic architecture.[2] The ablaq decorative technique is a derivative from the ancient Byzantine Empire, whose architecture used alternate sequential runs of light colored ashlar stone and darker colored orange brick.[4]

The first known use of the term ablaq in building techniques is in masonry work in reconstruction improvements to the walls of the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus. According to records, these reconstruction masonry improvements to the north wall began in the early twelfth century.[4] The local stone supply may have encouraged the use of alternating courses of light and dark stone. In the southern part of Syria there is abundance of black basalt as well as white-colored limestone. The supplies of each are about equal, so it was natural that masonry techniques of balanced proportions were used.[4]

The technique itself, however, was used much earlier, Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba being a notable example,[7] Medina Azahara, and possibly Al-Aqsa Mosque, as well as the Dome of the Rock.

The Mamluks utilized mottled light effects and chiaroscuro in their buildings, and among the architectural elements that complemented it was ablaq. Finely dressed ashlar stones was often combined with brickwork for vaults. These Mamluk and Syrian elements were applied and shared by the Ayyubids and Crusaders in Palestine, Syria, and Egypt.[8]

History[]

The technique of decorating buildings with ablaq masonry may derive from the Byzantine tradition of building with alternating layers of white ashlar stone and orange or reddish baked brick.[9] The first recorded use of ablaq masonry was found in repairs to the north wall of the Great Mosque of Damascus 1109.[9] In 1266 Sultan al-Zahir Baybars al-Bunduqdari built a palace in Damascus known as the Qasr Ablaq (Ablaq Palace), which was constructed with alterations of light and dark masonry. This name shows that the term ablaq was in regular usage for this type of masonry in the 13th century.[4][9]

The Mamluk architecture of Syria, Egypt and Palestine adopted the ablaq technique in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In these countries at about this time black and white stone were often used as well as red brick in recurring rows, giving a three colored striped building.[4]

The ablaq masonry technique is used in the Azm Palace in Damascus and other buildings of the Ottoman period. In fact, Dr.Andrew Petersen, Director of Research in at the University of Wales Lampeter states that ablaq (alternating courses of white limestone and black basalt is "A characteristic of the monumental masonry of Damascus.")[10]

At the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, ablaq lintels in alternating red and white courses are combined to highlight the voussoirs of the Great Arch.[11] Jerusalem mamluk architecture (period 1250 AD to 1516 AD) include multi-colored masonry in white, yellow, red and black.[12] The origins of the marble ablaq treatments at the Dome are controversial, some theorizing them original, and some saying they were later additions (and differing then as to the dates and identity of the builders).[5]

In Jordan, the Mamluk fortified khan at Aqaba (ca 1145) is a medieval fortress modeled after those used by the Crusaders. It contains an arch above the protected entrance. The horseshoe arch has ablaq masonry, harkening to Mamluk architecture in Egypt.[13]

Pisan ecclesiastical monuments—particularly the Cathedral of Pisa and Church of San Sepolcro (commenced building 1113)—used ablaq, not simple "black and white in revetment" between the conquest of Jerusalem in the First Crusade (1099) and the completion of the latter ca. 1130. Various architectural motifs—ablaq, the zigzag arch, and voussoir (rippled and plain) were used. These embellishments were a direct appropriation of Moslem architecture, resulting from pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and war against the Saracen in the First Crusade. Those visitors to Jerusalem could see ablaq at the Dome of the Rock, and at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as well as other examples that may no longer be extant. Thus zigzags (see Norman architecture) and ablaq became part of the repertoire of Romanesque architecture.[5][14]

South Carolina architect John Henry Devereux created a striking black and white ablaq edifice in the St. Matthew's German Evangelical Lutheran Church. However, that original conception has since been plastered over in monochrome red.[15]

References[]

- ^ Islamic Art and Architecture, p. 146

- ^ a b Rabbat, Nasser O. "10- The Emergence of the Citadel as Royal Residence". Aga Khan program for Islamic architecture. Massachusetts Institute of Technology School of Architecture. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f g Petersen, Andrew. "Ablaq". Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Digital Library. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ a b c Allen, Terry (2008). Pisa and the Dome of the Rock (electronic publication) (2nd ed.). Occidental, California: Solipsist Press. ISBN 978-0-944940-08-2. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ Vermeulen, Urbain; De Smet, D.; van Steenbergen, J. (1995). Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk eras. 3. p. 288. ISBN 978-90-6831-683-4. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ a b "Architecture". Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Avendano, Clarissa L. (2008–2009). "HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE 3, Islamic Architecture" (pdf). University of Santo Tomas, College of Architecture.

- ^ a b c Petersen, Andrew (March 14, 2007). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture (Reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-415-21332-5. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (October 3, 2011). "Damascus – history, arts and architecture". Islamic Arts & Architecture. Archived from the original on January 14, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ Walls 1990, pp. 18, 40, 144.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (March 11, 2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (September 9, 2011). "Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan – Architecture & History". Islamic Art & Architecture. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ Allen, Terry (1986). "4". A Classical Revival in Islamic Architecture. Wiesbaden.

- ^ "Charleston Historic District". National Register Historic Properties in South Carolina. South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

Bibliography[]

- Allen, Terry (2008). Pisa and the Dome of the Rock (electronic publication) (2nd ed.). Occidental, California: Solipsist Press. ISBN 978-0-944940-08-2. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- Petersen, Andrew (March 14, 2007). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture (Reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-415-21332-5. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- Walls, Archibald G. (December 31, 1990). Geometry and architecture in Islamic Jerusalem: a study of the Ashrafiyya. Scorpion Publishing Ltd. pp. 18, 40, 144. ISBN 978-0-905906-89-8. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

Further reading[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ablaq. |

- Rabbat, Nasser O. (1995). "The citadel of Cairo: a new interpretation of royal Mamluk architecture". Islamic History and Civilization. Leiden/New York: E.J. Brill. 14. ISBN 90-04-10124-1.

- Arches and vaults

- Architecture of Syria

- Byzantine architecture

- Arabic architecture

- Islamic architectural elements

- Mamluk architecture

- Masonry

- Moorish architecture

- Ornaments (architecture)

- Ottoman architecture

- Architecture of Lebanon

- Palestinian architecture

- Architecture of Jordan

- Architecture of Egypt