Bazaar

A bazaar or souk, is a permanently enclosed marketplace or street where goods and services are exchanged or sold.

The term bazaar originates from the Persian word bāzār. The term bazaar is sometimes also used to refer to the "network of merchants, bankers and craftsmen" who work in that area. Although the word "bazaar" is of Persian origin, its use has spread and now has been accepted into the vernacular in countries around the world.

The term bazaar is a common word in the Indian subcontinent: Hindi: बाज़ार, romanized: bazaar; Bengali: বাজার, romanized: baajaar; Nepali: बजार, romanized: bjaar.

The term souk (Arabic: سوق, romanized: sūq, Hebrew: שוק, romanized: shuq, Classical Syriac: ܫܘܩܐ, romanized: shuqa, Armenian: շուկա, romanized: shuka, Spanish: zoco, also spelled souq, shuk, shooq, soq, esouk, succ, suk, sooq, suq, soek) is used in Western Asian, Middle Eastern, North African and some Horn African cities (Amharic: ሱቅ sooq).[1][2]

Evidence for the existence of bazaars or souks dates to around 3,000 BCE. Although the lack of archaeological evidence has limited detailed studies of the evolution of bazaars, indications suggest that they initially developed outside city walls where they were often associated with servicing the needs of caravanserai. As towns and cities became more populous, these bazaars moved into the city center and developed in a linear pattern along streets stretching from one city gate to another gate on the opposite side of the city. Souks became covered walkways. Over time, these bazaars formed a network of trading centres which allowed for the exchange of produce and information. The rise of large bazaars and stock trading centres in the Muslim world allowed the creation of new capitals and eventually new empires. New and wealthy cities such as Isfahan, Vijaynagar, Surat, Cairo, Agra and Timbuktu were founded along trade routes and bazaars. Street markets are the European and North American equivalents.

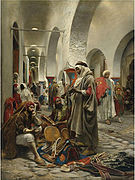

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Western interest in Oriental culture led to the publication of many books about daily life in Middle Eastern countries. Souks, bazaars and the trappings of trade feature prominently in paintings and engravings, works of fiction and travel writing.

Shopping at a bazaar or market-place remains a central feature of daily life in many Middle-Eastern and South Asian cities and towns and the bazaar remains the "beating heart" of West Asian and South Asian life; in the Middle East, souks tend to be found in a city's medina (old quarter). Bazaars and souks are often important tourist attractions. A number of bazaar districts have been listed as World Heritage sites due to their historical and/or architectural significance.

Terminology by region[]

In general a souk is synonymous with a bazaar or marketplace, and the term souk is used in Arabic-speaking countries.

Bazaar[]

The origin of the word bazaar comes from Persian bāzār,[3][4] from Middle Persian wāzār,[5] from Old Persian vāčar,[6] from Proto-Indo-Iranian *wahā-čarana.[7] The term, bazaar, spread from Persia into Arabia and ultimately throughout the Middle East.[8]

Differing meanings of “bazaar”[]

In North America, the United Kingdom and some other European countries, the term charity bazaar can be used as a synonym for a "rummage sale", to describe charity fundraising events held by churches or other community organisations in which either donated used goods (such as books, clothes and household items) or new and handcrafted (or home-baked) goods are sold for low prices, as at a church or other organisation's Christmas bazaar, for example.

Although Turkey offers many famous markets known as "bazaars" in English, the Turkish word "pazar" refers to an outdoor market held at regular intervals, not a permanent structure containing shops. English place names usually translate "çarşı" (shopping district) as "bazaar" when they refer to an area with covered streets or passages. For example, the Turkish name for the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is "Kapalıçarşı" (gated shopping area), while the Spice Bazaar is the "Mısır Çarşısı" (Egyptian shopping area).

In Czechia, the word "bazar" means second-hand shop. "Autobazar" is a shop which purchases and sells pre-owned cars.

Variations[]

In Indonesian, the word pasar means "market." The capital of Bali province, in Indonesia, is Denpasar, which means "north market."

Souk[]

The Arabic word is a loan from Aramaic "šūqā" (“street, market”), itself a loanword from the Akkadian "sūqu" (“street”, from "sāqu", meaning “narrow”). The spelling souk entered European languages probably through French during the French occupation of the Arab countries Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Thus, the word "souk" most likely refers to Arabic/North African traditional markets. Other spellings of this word involving the letter "Q" (sooq, souq, and so'oq) were likely developed using English and thus refer to Western Asian/Arab traditional markets, as there were several British colonies there during the 19th and 20th centuries.

In Modern Standard Arabic the term al-sooq refers to markets in both the physical sense and the abstract economic sense (e.g., an Arabic-speaker would speak of the sooq in the old city as well as the sooq for oil, and would call the concept of the free market السوق الحرّ as-sūq al-ḥurr).

Variations on "souk"[]

In northern Morocco, the Spanish corruption socco is often used as in the Grand Socco and Petit Socco of Tangiers.

In the Indian subcontinent the 'chowk' is often used in place of which comes from Sanskrit चतवार, meaning four। Chowk is always a four cross road. The term is used generally to designate the market in any Western Asian city, but may also be used in Western cities, particularly those with a Muslim community.

In Malta, the terms suq and sometimes monti are used for a marketplace.

In the United States, especially in Southern California and Nevada, an indoor swap meet is a type of bazaar, i.e. a permanent, indoor shopping center open during normal retail hours, with fixed "booths" or counters for the vendors.[9][10][11]

History[]

Origins[]

Bazaars originated in the Middle East, probably in Persia.[citation needed] Pourjafara et al., point to historical records documenting the concept of a bazaar as early as 3001 BC.[12] By the 4th century (CE), a network of bazaars had sprung up alongside ancient caravan trade routes. Bazaars were typically situated in close proximity to ruling palaces, citadels or mosques, not only because the city afforded traders some protection, but also because palaces and cities generated substantial demand for goods and services.[13] Bazaars located along these trade routes, formed networks, linking major cities with each other and in which goods, culture, people and information could be exchanged.[14]

The Greek historian, Herodotus, noted that in Egypt, roles were reversed compared with other cultures and Egyptian women frequented the market and carried on trade, while the men remain at home weaving cloth.[15] He also described The Babylonian Marriage Market.[16]

Documentary sources point to permanent marketplaces in Middle Eastern cities from as early as 550 BCE.[17] A souk was originally an open-air marketplace. Historically, souks were held outside cities at locations where incoming caravans stopped and merchants displayed their goods for sale. Souks were established at caravanserai, places where a caravan or caravans arrived and remained for rest and refreshments. Since this might be infrequent, souks often extended beyond buying and selling goods to include major festivals involving various cultural and social activities. Any souk may serve a social function as being a place for people to meet in, in addition to its commercial function.[18] These souks or bazaars formed networks, linking major cities with each other in which goods, culture, people and information could be exchanged.[14]

Prior to the 10th century, bazaars were situated on the perimeter of the city or just outside the city walls. Along the major trade routes, bazaars were associated with the caravanserai. From around the 10th century, bazaars and market places were gradually integrated within the city limits. The typical bazaar was a covered area where traders could buy and sell with some protection from the elements.[19] Over the centuries, the buildings that housed bazaars became larger and more elaborate. The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is often cited as the world's oldest, one of the biggest and continuously-operating, purpose-built market; its construction began in 1455.

From the 10th century to modern times[]

From around the 10th century, as major cities increased in size, the souk or marketplace shifted to the center of urban cities where it spread out along the city streets, typically in a linear pattern.[20] Around this time, permanent souks also became covered marketplaces.[21]

City bazaars occupied a series of alleys along the length of the city, typically stretching from one city gate to a different gate on the other side of the city. The Bazaar of Tabriz, for example, stretches along 1.5 kilometres of street and is the longest vaulted bazaar in the world.[22] Moosavi argues that the Middle-Eastern bazaar evolved in a linear pattern, whereas the market places of the West were more centralised.[20]

In pre-Islamic Arabia, two types of bazaar existed: permanent urban markets and temporary seasonal markets. The temporary seasonal markets were held at specific times of the year and became associated with particular types of produce. Suq Hijr in Bahrain was noted for its dates while Suq 'Adan was known for its spices and perfumes. In spite of the centrality of the Middle East in the history of bazaars, relatively little is known due to the lack of archaeological evidence. However, documentary sources point to permanent marketplaces in cities from as early as 550 BCE.[23]

Nejad has made a detailed study of early bazaars in Iran and identifies two distinct types, based on their place within the economy, namely:[24]

- * Commercial bazaars (or retail bazaars): emerged as part of an urban economy not based on a merchant system

- * Socio-commercial bazaars: formed in economies based on a merchant system, socio-economic bazaars are situated on major trade routes and are well integrated into the city's structural and spatial systems

In the 1840s, Charles White described the Yessir Bazary of Constantinople in the following terms:[25]

- "The interior consists of an irregular quadrangle. In the center is a detached building, the upper portion serving as a lodging for slavedealers, and underneath are cells for newly imported slaves. To this is attached a coffee-house, and near to it a half-ruined mosque. Around the three habitable sides of the court runs an open colonnade, supported by wooden columns, and approached by steps at an angle. Under the colonnade are platforms, separated from each other by low railings and benches. Upon these, dealers and customers may be seen during business hours smoking and discussing prices.

- Behind these platforms are ranges of small chambers, divided into two compartments by a trellice-work. The habitable part is raised about three feet from the ground; the remainder serves as passage and cooking place. The front portion is generally tenanted by black, and the rear by white slaves. These chambers are exclusively devoted to females. Those to the north and west are destined for second hand negresses or white women – that is, for slaves who have been previously purchased and instructed, and are sent to be resold. The hovels to the east are reserved for newly imported negresses, or black and white women of low price.

- The platforms are divided from the chambers by a narrow alley, on the wall side of which are benches, where women are exposed for sale. This alley serves as a passage of communication and walk for the brokers, who sell slaves by auction and on commission. In this case, the brokers walk around, followed by the slaves, and announce the price offered. Purchasers, seated on the platforms, then examine, question and bid, as suits their fancy, until at length the woman is sold or withdrawn."

21st century[]

In the Middle East, the bazaar is considered to be "the beating heart of the city and a symbol of Islamic architecture and culture of high significance."[26] Today, bazaars are popular sites for tourists and some of these ancient bazaars have been listed as world heritage sites or national monuments on the basis of their historical, cultural or architectural value.

The Medina of Fez, Morocco, with its labyrinthine covered market streets was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981.[27] Al-Madina Souq is part of the ancient city of Aleppo in Syria, another UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986.[28] The Bazaar complex at Tabriz, Iran was listed in 2010[29] and Kemeraltı Bazaar of İzmir in 2020.[30] The Bazaar of Qaisiyariye in Lar, Iran is on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[31]

Types[]

Seasonal[]

A temporary, seasonal souk is held at a set time that might be yearly, monthly or weekly. The oldest souks were set up annually, and were typically general festivals held outside cities. For example, Souk Ukadh was held yearly in pre-Islamic times in an area between Mecca and Ta’if during the sacred month of Dhu al-Qi'dah. While a busy market, it was more famous for its poetry competitions, judged by prominent poets such as Al-Khansa and Al-Nabigha. An example of an Islamic annual souk is just outside Basra, also famed for its poetry competitions in addition to its storytelling activities.[24] Temporary souks tended to become known for specific types of produce. For example, Suq Hijr in Bahrain was noted for its dates while Suq 'Adan was known for its spices and perfumes.[32] Political, economic and social changes have left only the small seasonal souks outside villages and small towns, primarily selling livestock and agricultural products.

Weekly markets have continued to function throughout the Arab world. Most of them are named from the day of the week on which they are held. They usually have open spaces specifically designated for their use inside cities. Examples of surviving markets are the Wednesday Market in Amman that specializes in the sale of used products, the market held every Friday in Baghdad specializing in pets; the Fina’ Market in Marrakech offers performance acts such as singing, music, acrobats and circus activities.

In tribal areas, where seasonal souks operated, neutrality from tribal conflicts was usually declared for the period of operation of a souk to permit the unhampered exchange of surplus goods. Some of the seasonal markets were held at specific times of the year and became associated with particular types of produce such as Suq Hijr in Bahrain, noted for its dates while Suq 'Adan was known for its spices and perfumes. In spite of the centrality of the Middle Eastern market place, relatively little is known due to the lack of archaeological evidence.[33]

Permanent[]

Permanent souks are more commonly occurring, but less renowned as they focus on commercial activity, not entertainment. Until the Umayyad era, permanent souks were merely an open space where merchants would bring in their movable stalls during the day and remove them at night; no one had a right to specific pitch and it was usually first-come first-served. During the Umayyad era the governments started leasing, and then selling, sites to merchants. Merchants then built shops on their sites to store their goods at night. Finally, the area comprising a souk might be roofed over. With its long and narrow alleys, al-Madina Souk is the largest covered historic market in the world, with an approximate length of 13 kilometers.[34] Al-Madina Souk is part of the Ancient City of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986.[28]

Organization[]

Gharipour has pointed out that in spite of the centrality of souks and bazaars in Middle Eastern history, relatively little is known due to the lack of archaeological evidence.[33] Souks are traditionally divided into specialized sections dealing in specific types of product, in the case of permanent souks each usually housed in a few narrow streets and named after the product it specializes in such as the gold souk, the fabric souk, the spice souk, the leather souk, the copy souk (for books), etc. This promotes competition among sellers and helps buyers easily compare prices.

At the same time the whole assembly is collectively called a souk. Some of the prominent examples are Souk Al-Melh in Sana'a, Manama Souk in Bahrain, Bizouriyya Souk in Damascus, Saray Souk in Baghdad, Khan Al-Zeit in Jerusalem, and Zanqat Al-Niswaan in Alexandria.

Though each neighbourhood within the city would have a local Souk selling food and other essentials, the main souk was one of the central structures of a large city, selling durable goods, luxuries and providing services such as money exchange. Workshops where goods for sale are produced (in the case of a merchant selling locally-made products) are typically located away from the souk itself. The souk was a level of municipal administration. The Muhtasib was responsible for supervising business practices and collecting taxes for a given souk while the Arif are the overseers for a specific trade.

Shopping at a souk or market place is part of daily life throughout much of the Middle East.[35] Prices are commonly set by bargaining, also known as haggling, between buyers and sellers.[36]

In art and literature – Orientalism[]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Europeans conquered and excavated parts of North Africa and the Levant. These regions now make up what is called the Middle East, but in the past were known as the Orient. Europeans sharply divided peoples into two broad groups – the European West and the East or Orient; us and the other. Europeans often saw Orientals as the opposite of Western civilisation; the peoples could be threatening- they were "despotic, static and irrational whereas Europe was viewed as democratic, dynamic and rational."[37] At the same time, the Orient was seen as exotic, mysterious, a place of fables and beauty. This fascination with the other gave rise to a genre of painting known as Orientalism. A proliferation of both Oriental fiction and travel writing occurred during the early modern period.

Subject matter[]

Many of these works were lavishly illustrated with engravings of every day scenes of Oriental lifestyles, including scenes of market places and market trade.[38] Artists focused on the exotic beauty of the land – the markets, caravans and snake charmers. Islamic architecture also became favorite subject matter. Some of these works were propaganda designed to justify European imperialism in the East, however many artists relied heavily on their everyday experiences for inspiration in their artworks.[39] For example, Charles D'Oyly, who was born in India, published the Antiquities of Dacca featuring a series of 15 engraved plates of Dacca [now Dhaka, Bangladesh] featuring scenes of markets, commerce, buildings and streetscapes.[40] European society generally frowned on nude painting – but harems, concubines and slave markets, presented as quasi-documentary works, satisfied European desires for pornographic art. The Oriental female wearing a veil was a particularly tempting subject because she was hidden from view, adding to her mysterious allure.[41]

Notable Orientalist artists[]

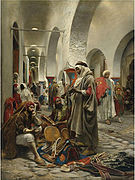

Notable artists in the Orientalist genre include: Jean-Léon Gérôme Delacroix (1824–1904), Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803–1860), Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), Eugène Alexis Girardet 1853-1907 and William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) who all found inspiration in Oriental street scenes, trading and commerce. French painter Jean-Étienne Liotard visited Istanbul in the 17th century and painted pastels of Turkish domestic scenes. British painter John Frederick Lewis who lived for several years in a traditional mansion in Cairo, painted highly detailed works showing realistic genre scenes of Middle Eastern life. Edwin Lord Weeks was a notable American example of a 19th-century artist and author in the Orientalism genre. His parents were wealthy tea and spice merchants who were able to fund his travels and interest in painting. In 1895 Weeks wrote and illustrated a book of travels titled From the Black Sea through Persia and India. Other notable painters in the Orientalist genre who included scenes of street life and market-based trade in their work are Jean-Léon Gérôme Delacroix (1824–1904), Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803–1860), Frederic Leighton (1830–1896), Eugène Alexis Girardet 1853–1907 and William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), who all found inspiration in Oriental street scenes, trading and commerce.[42]

Orientalist literature[]

A proliferation of both Oriental fiction and travel writing occurred during the early modern period.[43]

Many English visitors to the Orient wrote narratives around their travels. British Romantic literature in the Orientalism tradition has its origins in the early eighteenth century, with the first translations of The Arabian Nights (translated into English from the French in 1705–08). The popularity of this work inspired authors to develop a new genre, the Oriental tale. Samuel Johnson's History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia, (1759) is mid-century example of the genre.[44] Byron's Oriental Tales, is another example of the Romantic Orientalism genre.[45]

Although these works were purportedly non-fiction, they were notoriously unreliable. Many of these accounts provided detailed descriptions of market places, trading and commerce.[46] Examples of travel writing include: Les Mysteres de L'Egypte Devoiles by Olympe Audouard published in 1865[47] and Jacques Majorelle's Road Trip Diary of a Painter in the Atlas and the Anti-Atlas published in 1922[48]

Gallery of paintings and watercolours[]

- Selected paintings & watercolours with bazaar scenes as subject matter

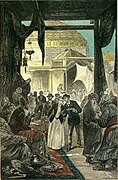

Bazaar in Samarkand, illustration by Léon Benett for a Jules Verne novel, 1893

A Bazaar, Oil painting, Wellcome

The Bazaar, by Alexandre Defaux, 1856

The Silk Bazaar by Amedeo Preziosi, late 19th century

Souk des étoffes, Tunis by Anton Robert Leinweber, before 1921

Carpet Merchant in the Khan el Khaleel, 1878

Cashmere Travellers in a Street of Delhi by Edwin Lord Weeks 1880

Inside the Souk, Cairo by Charles Wilda, 1892

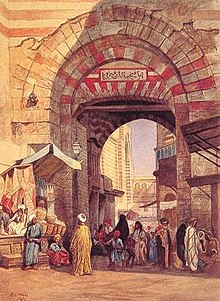

Bazaar of the Coppersmiths by David Roberts, 1838

Bazaar El Moo Ristan, by David Roberts, 1838

Gallery of photographs[]

Bazaar in Sanandaj, Iran

in Aleppo, Syria

Muristan Souk entrance in Jerusalem

Spice Market, Marrakesh

Ouarzazate souk.

Covered souks in Bur Dubai

Souk in Tripoli

List of bazaars and souks[]

See also[]

- Types of markets, bazaars and souks

- Bazaari

- Bedesten (also known as bezistan, bezisten, bedesten) refers to a covered bazaar and an open bazaar in the Balkans.

- Haat bazaar – (also known as a hat) an open air bazaar or market in South Asia.

- Landa bazaar – a terminal market or market for second hand goods (South Asia), such as Medina quarter.

- Meena Bazaar – a bazaar that raises money for non-profit organisations.

- Pasar malam – a night market in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore that opens in the evening, typically held in the street in residential neighbourhoods.

- Pasar pagi – a morning market, typically a wet market that trades from dawn until midday, found in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. A Wet market sells fresh meat, and produce. See also Dry goods.

- Markets and retail in general

- Arcade – a covered passageway with stores along one or both sides.

- History of marketing

- Marketplace

- Merchant

- Peddler

- Retail

- Shopping mall

- Shōtengai - a style of Japanese commercial district, typically in the form of a local market street that is closed to vehicular traffic.

References[]

- ^ "Aleppo.us: Old souks of Aleppo (in Arabic)".

- ^ "Mahane Yehuda website". Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ "bazaar - Origin and meaning of bazaar by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Ayto, John (1 January 2009). Word Origins. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4081-0160-5.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (16 February 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-973215-9.

- ^ "Bazaar". Dictionary.com, LLC. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Benveniste, Émile; Lallot, Jean (1 January 1973). "Chapter Nine: Two Ways of Buying". Indo-European Language and Society. University of Miami Press. Section Three: Purchase. ISBN 978-0-87024-250-2.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/bazaar

- ^ Staff, Sun (February 28, 2019). "Las Vegas' epic secondhand shops, antique stores and swap meets are a thrifter's paradise - Las Vegas Sun Newspaper". lasvegassun.com.

- ^ "Tensions, Bargains Share Space at Indoor Swap Meets : Bazaars: Businesses that survived riots are prospering. But some say they sell shoddy goods and stir racial strife". Los Angeles Times. July 8, 1992.

- ^ "Young businesses thrive in indoor swap meets". Las Vegas Review-Journal. 2014-08-17. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ Pourjafara, M., Aminib, M., Varzanehc, and Mahdavinejada, M., "Role of bazaars as a unifying factor in traditional cities of Iran: The Isfahan bazaar," Frontiers of Architectural Research, Vol. 3, No. 1, March 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2013.11.001, pp 10–19; Mehdipour, H.R.N, "Persian Bazaar and Its Impact on Evolution of Historic Urban Cores: The Case of Isfahan," The Macrotheme Review [A multidisciplinary Journal of Global Macro Trends], Vol. 2, no. 5, 2013, p.13

- ^ Harris, K., "The Bazaar" The United States Institute of Peace, <Online: http://iranprimer.usip.org/resource/bazaar>

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hanachi, P. and Yadollah, S., "Tabriz Historical Bazaar in the Context of Change," ICOMOS Conference Proceedings, Paris, 2011

- ^ Thamis, "Herodotus on the Egyptians." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 18 Jan 2012. Web. 20 Aug 2017.

- ^ Herodotus: The History of Herodotus, Book I (The Babylonians), c. 440BC, translated by G.C. Macaulay, c. 1890

- ^ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 3-15

- ^ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012 pp 14-15

- ^ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012 pp 14–15

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moosavi, M. S. Bazaar and its Role in the Development of Iranian Traditional Cities [Working Paper], Tabriz Azad University, Iran, 2006

- ^ Mehdipour, H.R.N, "Persian Bazaar and Its Impact on Evolution of Historic Urban Cores: The Case of Isfahan," The Macrotheme Review [A multidisciplinary Journal of Global Macro Trends], Vol. 2, no. 5, 2013, p.13

- ^ Mehdipour, H.R.N, "Persian Bazaar and Its Impact on Evolution of Historic Urban Cores: The Case of Isfahan," The Macrotheme Review [A multidisciplinary Journal of Global Macro Trends], Vol. 2, no. 5, 2013, p.14

- ^ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 4–5

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nejad, R. M., “Social bazaar and commercial bazaar: comparative study of spatial role of Iranian bazaar in the historical cities in different socio-economical context,” 5th International Space Syntax Symposium Proceedings, Netherlands: Techne Press, D., 2005,

- ^ Cited in: Stewart, F., Shackles of Iron: Slavery Beyond the Atlantic: Critical Themes in World History, 2016

- ^ Karimi, M., Moradi, E. and Mehr, R., "Bazaar, As a Symbol of Culture and the Architecture of Commercial Spaces in Iranian-Islamic Civilization,"

- ^ UNESCO, Medina of Fez, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/170

- ^ Jump up to: a b "eAleppo:Aleppo city major plans throughout the history" (in Arabic).

- ^ UNESCO, Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1346

- ^ "Turkey's bazaar added to temporary UNESCO Heritage list". www.aa.com.tr.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Bazaar of Qaisariye in Laar - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org.

- ^ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, p. 4

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 4-5

- ^ "eAleppo: The old Souks of Aleppo (in Arabic)". Esyria.sy. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "Doha's Sprawling Souk Enters the Modern Era, The National [UAE edition], 25 February 2011, " https://www.thenational.ae/business/travel-and-tourism/doha-s-sprawling-souk-enters-the-modern-age-1.420872; Ramkumar, E.S., "Eid Shopping Reaches Crescendo," Arab News, 13 October 2007, http://www.arabnews.com/node/304533

- ^ Islam, S., "Perfecting the Haggle," The National, [UAE edition], 27 March 2010, https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/perfecting-the-haggle-why-it-s-always-worth-walking-away-1.546397

- ^ Nanda, S. and Warms, E.L., Cultural Anthropology, Cengage Learning, 2010, p. 330

- ^ Houston, C., New Worlds Reflected: Travel and Utopia in the Early Modern Period, Routledge, 2016

- ^ Meagher, J., "Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art," [The Metropolitan Museum of Art Essay], Online: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hd_euor.htm

- ^ D'Oyly, Charles, Antiquities of Dacca, London, J. Landseer, 1814 as cited in Bonham's Fine Books and Manuscripts Catalogue, 2012, https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/20048/lot/2070/

- ^ Nanda, S. and Warms, E.L., Cultural Anthropology, Cengage Learning, 2010, pp 330–331

- ^ Davies, K., Orientalists: Western Artists in Arabia, the Sahara, Persia, New York, Laynfaroh, 2005; Meagher, J., "Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art," [The Metropolitan Museum of Art Essay], Online: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hd_euor.htm

- ^ Houston, C., New Worlds Reflected: Travel and Utopia in the Early Modern Period, Routledge, 2016

- ^ "The Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Romantic Age: Topic 4: Overview". www.wwnorton.com.

- ^ Kidwai, A.R., Literary Orientalism: A Companion, New Delhi, Viva Books, 2009, ISBN 978-813091264-6

- ^ MacLean, G., The Rise of Oriental Travel: English Visitors to the Ottoman Empire, 1580–1720, Palgrave, 2004, p. 6

- ^ Audouard, O. (de Jouval), Les Mystères de l'Égypte Dévoilés, (French Edition) (originally published in 1865), Elibron Classics, 2006

- ^ Marcilhac, F., La Vie et l'Oeuvre de Jacques Majorelle: 1886–1962, [The Orientalists Volume 7], ARC Internationale edition, 1988.

Further reading[]

- The Persian Bazaar: Veiled Space of Desire (Mage Publications) by Mehdi Khansari

- The Morphology of the Persian Bazaar (Agah Publications) by Azita Rajabi.

- Assari, Ali; T.M.Mahesh (December 2011). "Compararative Sustainability of Bazaar in Iranian Traditional Cities: Case Studies in Isfahan and Tabriz" (PDF). International Journal on Technical and Physical Problems of Engineering. 3 (9): 18–24. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

External links[]

| Look up bazaar in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bazaars. |

- Iran Chamber Society on Architecture of the Bazaar at Isfahan

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 559.

- Bazaars

- Islamic culture

- Persian words and phrases

- Iranian folklore

- Shopping (activity)