Jali

A jali or jaali, (jālī, meaning "net") is the term for a perforated stone or latticed screen, usually with an ornamental pattern constructed through the use of calligraphy, geometry or natural patterns. This form of architectural decoration is common in Indo-Islamic architecture and more generally in Islamic architecture.[1]

According to Yatin Pandya, the jali allows light and air while minimizing the sun and the rain. Also when the air passes through these openings, its velocity increases giving profound diffusion.[2][clarification needed] The holes are often nearly of the same width or smaller than the thickness of the stone, thus providing structural strength. It has been observed that humid areas like Kerala and Konkan have larger holes with overall lower opacity than compared with the dry climate regions of Gujarat and Rajasthan.[2]

With the widespread use of glass in the late 19th century, and compactness of the residential areas in the modern India, jalis became less frequent for privacy and security matters.[3]

History[]

Basic rectangular Jali stone work is seen at the Gupta period Nachna Hindu temples and the post Gupta Pattadakal temples. In China wood lattice work developed during the Han dynasty, the tradition has continued in modern Chinese architecture.[4] Sanskrit texts on architecture Silpa (650 AD), Samarangana-Sutradhara of King Bhoja (1018-1054 AD), Kāśyapā-Śilpā (1300) and Śilpā-Ratnam of sixteenth century mention or discuss jalis.[5]

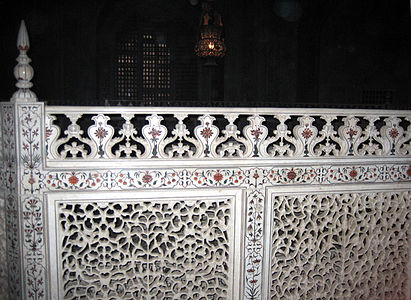

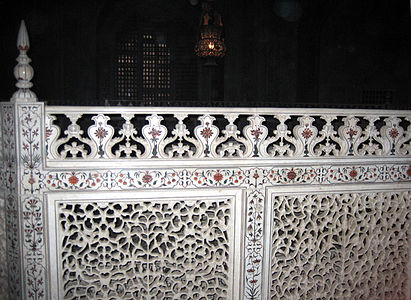

Early jali work with multiple geometric shapes was built by carving into stone, in geometric patterns,\ first appears in the Alai Darwaza of 1305 at Delhi besides the Qutub Minar, while later the Mughals used very finely carved plant-based designs, as at the Taj Mahal. They also often added pietra dura inlay to the surrounds, using marble and semi-precious stones.[1][6]

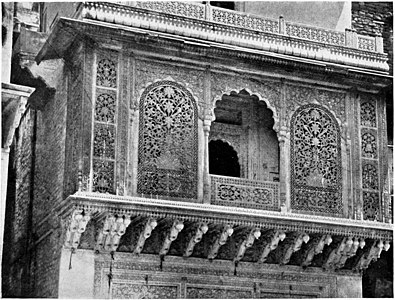

In the Gwalior fort, near the Urwahi gate, there is a 17 line inscription dated Samvat 1553, mentioning names of some craftsmen and their creations. One of them is Khedu, who was an expert in "Gwaliyai jhilmili" i.e. jali screen crafted in the Gwalior style.[7] The Mughal period tomb of Muhammad Ghaus built in 1565 AD at Gwalior is remarkable for its stone jalis. [8]Many of the Gwalior's 19th century houses used stone jalis. Jalis are used extensively in Gwalior's Usha Kiran Palace Hotel, formerly Scindia's guest house.

Museum collections[]

Some of the jalis are in major museums in USA and Europe. These include Indianapolis Museum of Art [9] and Metropolitan Museum of Art[10] and Victoria and Albert Museum.[11]

See also[]

- Girih

- Jharokha

- Openwork

- Venturi effect

Illustrations[]

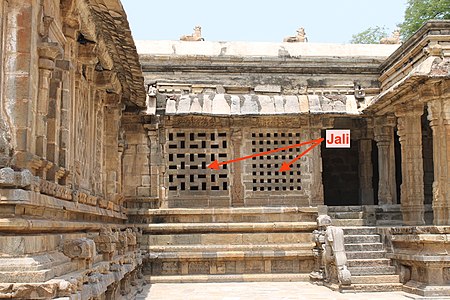

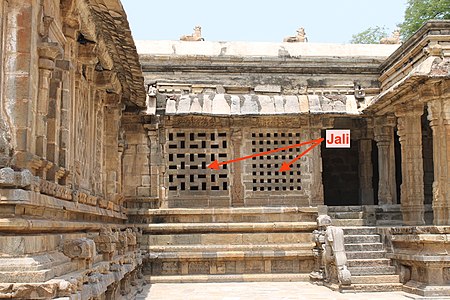

Nachna Parvati-Temple Jali, Gupta period

Pattadakal window

another window at Pattadakal

Pattadakal Virupaksa temple window

Chola temple

Window at Alai Darwaza, Qutb complex

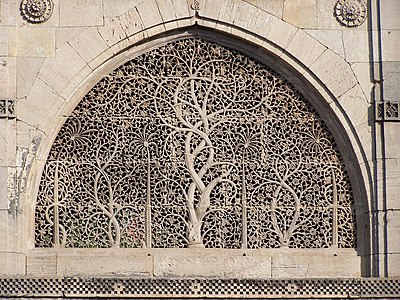

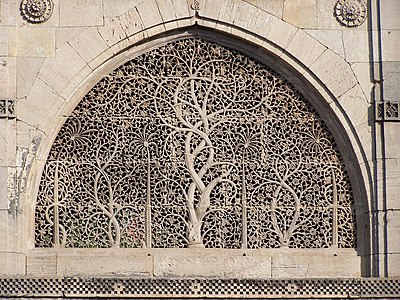

Jali in Sidi Saiyyed mosque in Ahmedabad exhibiting traditional Indian tree of life motif

Jali at Tomb of Salim Chishti, Fatehpur Sikri shows Islamic geometric patterns developed in western asia

Details of marble Jali screens around royal cenotaphs, Taj Mahal

Jali at Bibi Ka Maqbara, Aurangabad with typical Indian motifs

Jali at Champaner utilize traditional indian geometric patterns and Islamic geometry

Jalis in Mohammad Gaus Tomb Gwalior

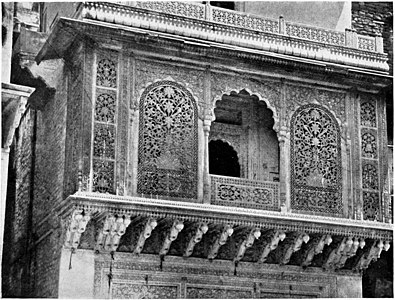

19th century houses in Gwalior

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lerner, p. 156

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pandya

- ^ Satyaprakash Varanashi (30 January 2011). "The multi-functional jaali". The Hindu. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ A Journey through Chinese Windows and Doors – an Introduction to Chinese Mathematical Art, Miroslaw Majewski, Jiyan Wang, Fourteenth Asian Technology Conference in Mathematics, 17 - 21 December, 2009

- ^ Masooma Abbas, Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors, Int. Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016, p. 135-147

- ^ Thapar, Bindia (2004). Introduction to Indian architecture. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 9781462906420.

- ^ Hariharnivas Dvidedi, Gwalior ke Tomar, 1976, p. 378-380

- ^ Nonperiodic Octagonal Patterns from a Jali Screen in the Mausoleum of Muhammad Ghaus in Gwalior and Their Periodic Relatives, Emil Makovicky & Nicolette M. Makovicky ,Nexus Network Journal volume 19, pages 101–120 (2017)

- ^ JALI PANEL (INDIA), LATE 19TH CENTURY

- ^ Pierced Window Screen (Jali) early 17th century

- ^ [https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O430678/one-of-twenty-nine-drawings-drawing-unknown/ Drawing ca.1882 (made)]

References[]

- Lerner, Martin (ed), The Flame and the Lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian Art from the Kronos Collections, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Jali (no. 60), google books

- Pandya, Yatin, Yatin Pandya on 'jaali' as a traditional element, Daily News and Analysis, 16 October 2011, access-date=18 January 2016

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jali. |

- Indian architectural styles

- Mughal architecture

- Islamic architectural elements

- Islamic architecture

- Architectural elements