Four-centred arch

A four-centered arch is a low, wide type of arch with a pointed apex. Its structure is achieved by drafting two arcs which rise steeply from each springing point on a small radius, and then turning into two arches with a wide radius and much lower springing point. It is a pointed sub-type of the general flattened depressed arch. Two of the most notable types are known as the Persian arch, which is moderately "depressed", and the Tudor arch, which is much flatter.

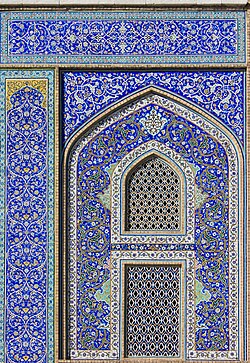

This type of arch uses space efficiently and decoratively when used for doorways. It is also employed as a wall decoration in which arcade and window openings form part of the whole decorative surface.

It is a mainstay of Islamic architecture, especially Persian and Mughal architecture; in the latter the lowest arches often have scalloped edges. In Asia it typically has a less depressed form than in "Tudor"-style examples.

In English architecture, it is often known as a Tudor arch, as it was a common architectural element during the reigns of the Tudor dynasty (1485–1603), though its use predates 1485 by several decades, and from about 1550 it was out of fashion for grand buildings. It is a blunted version of the pointed arch of Gothic architecture, of which Tudor architecture is the last phase in England.[1]

Use in Islamic architecture[]

The four-centered arch is widely used in Islamic architecture, originally employed by the Abbasids and especially that of Persianate cultures, including Mughal architecture as well as Persian architecture. For example, almost all iwans use this type of arch. It was especially common in the architecture of the Timurid Empire and its successor states. The earliest examples of a four-centered arch are in the portals of the Qubbat al-Sulaiybiyya, an octagonal pavilion, and the Qasr al-'Ashiq palace, both at Samarra, where the Abbasid caliphs constructed a purpose-built capital city for their empire in the 9th century.[2]

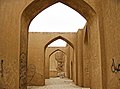

Restored 9th century arches of the Qasr al-'Ashiq, Samarra.

The 11th/12th century , Raqqa.

The 16th century western gate of the Purana Qil'a fortress, Delhi.

The 16th century Jama Mosque in Bijapur with rib vaulting consisting of four-centred arches.

The 16th century Jahangiri Mahal at the Agra Fort has a four-centred arched gateway flanked by four-centred blind arches.

The 17th century Taj Mahal mausoleum of Mumtaz Mahal in Agra.

The 17th century south-eastern gateway of the Lalbagh Fort in Dhakkar.

The 17th century Bara Kaman mausoleum of Ali Adil Shah II in Bijapur.

Use in English architecture[]

The Tudor arch was especially used for doorways, where it gives a wide opening without taking too much space above, compared to a more pointed Gothic arch. In Tudor architecture of the grander sort it is so used when the window openings are rectangular, as for example at Hampton Court Palace. In such cases it can be even flatter than usual, and may not be four-centered in terms of geometry, with some of the upper edges effectively straight.

A notable early example is the west window of Gloucester Cathedral. There are three royal chapels and one chapel-like Abbey which show the style at its most elaborate: King's College Chapel, Cambridge; St George's Chapel, Windsor; Henry VII's Chapel at Westminster Abbey, and Bath Abbey. However, numerous simpler buildings, especially churches, built during the wool boom in East Anglia, also demonstrate the style.

When employed to frame a large church window, it lends itself to very wide spaces, decoratively filled with many narrow vertical mullions and horizontal transoms. The overall effect produces a grid-like appearance of regular, delicate, rectangular forms with an emphasis on the perpendicular, characteristic of the style, known as Perpendicular Gothic in England, of the 15th and early 16th centuries. This is very similar to contemporary Spanish style in particular. In buildings such as Hampton Court the Tudor arch is found together with the first appearance of Renaissance architecture in England, much later than in Italy. In the later period it is generally only used for major decorative windows, perhaps in an oriel window, or a bay window supported on a bracket or corbel.[4][5]

Gloucester Cathedral, west window, c. 1420

King's College Chapel, Cambridge, begun 1446

Great Gate, Trinity College, Cambridge (inside), 1519–35

Clock Court gatehouse, Hampton Court Palace, c. 1520

St. George's Chapel, Windsor, east window, 1475–1528

Small doorway, now blocked, in a church

Notes[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tudor arches. |

- ^ Augustus Pugin, Specimens of Gothic Architecture: Selected from Various Ancient Edifices in England, 1821, Volumes 1-2, google books

- ^ Petersen, A. Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, London, 2002, pp. 25 & 250-251.

- ^ C E Bosworth and M S Asimov (eds.) History of Civilizations of Central Asia, v. 4: The Age of achievement, A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century; Pt. II: the achievements, Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 2000, pp. 574.

- ^ "Tudor Architecture in England 1500-1575". Retrieved 2007-02-15.

- ^ John Poppeliers, Nancy Schwartz (1983). What Style is It?. New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 106. ISBN 0-471-14434-7.

- Arches and vaults

- Islamic architectural elements