J. K. Rowling

J. K. Rowling CH OBE HonFRSE FRCPE FRSL | |

|---|---|

Rowling at the White House in 2010 | |

| Born | Joanne Rowling 31 July 1965 Yate, Gloucestershire, England |

| Pen name |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | University of Exeter Moray House |

| Period | 1997–present |

| Genre |

|

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

| jkrowling | |

Joanne Rowling CH, OBE, HonFRSE, FRCPE, FRSL (/ˈroʊlɪŋ/ ROH-ling;[1] born 31 July 1965), better known by her pen name J. K. Rowling, is a British author, philanthropist, film producer, and screenwriter. She is author of the Harry Potter fantasy series, which has won multiple awards and sold more than 500 million copies,[2][3] becoming the best-selling book series in history.[4] The books are the basis of a popular film series, over which Rowling had overall approval on the scripts[5] and was a producer on the final films.[6] She also writes crime fiction under the pen name Robert Galbraith.

Born in Yate, Gloucestershire, Rowling was working as a researcher and bilingual secretary for Amnesty International in 1990 when she conceived the idea for the Harry Potter series while on a delayed train from Manchester to London.[7] The seven-year period that followed saw the death of her mother, birth of her first child, divorce from her first husband, and relative poverty until the first novel in the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, was published in 1997. There were six sequels, of which the last was released in 2007. Since then, Rowling has written several books for adult readers: The Casual Vacancy (2012) and—under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith—the crime fiction Cormoran Strike series.[8] In 2020, her "political fairytale" for children, The Ickabog, was released in instalments in an online version.[9]

Rowling has lived a "rags to riches" life in which she progressed from living on benefits to being named the world's first billionaire author by Forbes.[10] Rowling disputed the assertion, saying she was not a billionaire.[11] Forbes reported that she lost her billionaire status after giving away much of her earnings to charity.[12] Her UK sales total in excess of £238 million, making her the best-selling living author in Britain.[13] The 2021 Sunday Times Rich List estimated Rowling's fortune at £820 million, ranking her as the 196th richest person in the UK.[14] Rowling was appointed a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in the 2017 Birthday Honours for services to literature and philanthropy. Rowling has supported multiple charities, including Comic Relief, One Parent Families, and Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain, as well as launching her own charity, Lumos.

Time named her a runner-up for its 2007 Person of the Year, noting the social, moral, and political inspiration she has given her fans.[15] In October 2010, she was named the "Most Influential Woman in Britain" by leading magazine editors.[16] Rowling has voiced views on UK politics, especially in opposition to Scottish independence and Brexit, and has been critical of her relationship with the press. Since late 2019, Rowling has publicly voiced her opinions on transgender people and related civil rights. These views have been criticised as transphobic by LGBT rights organisations and some feminists, but have received support from some other feminists and individuals.

Name

Although she writes under the pen name J. K. Rowling, before her remarriage her name was Joanne Rowling. Her publishers asked that she use two initials rather than her full name, anticipating the possibility of the target audience of young boys not wanting to read a book written by a woman.[17] As she had no middle name, she chose K (for Kathleen) as the second initial of her pen name, from her paternal grandmother.[17] She calls herself Jo.[18] Following her remarriage, she has sometimes used the name Joanne Murray when conducting personal business.[19][20] During the Leveson Inquiry, she gave evidence under the name of Joanne Kathleen Rowling[21] and her entry in Who's Who lists her name also as Joanne Kathleen Rowling.[22]

Life and career

Birth and family

Joanne Rowling was born on 31 July 1965[23][24] in Yate, Gloucestershire,[25][26] to Anne (née Volant), a science technician, and Peter James Rowling, a Rolls-Royce aircraft engineer.[27][28] Her parents first met on a train departing from King's Cross Station bound for Arbroath in 1964.[29] They married on 14 March 1965.[29] One of Rowling's maternal great-grandfathers, Dugald Campbell, was a Scottish man from Lamlash.[30][31] Her mother's French paternal grandfather, Louis Volant,[32] was awarded the War Cross for exceptional bravery in defending the village of Courcelles-le-Comte during World War I. Rowling originally believed Volant had won the Legion of Honour during the war, as she said when she received it herself in 2009. She later discovered the truth when featured in an episode of the UK genealogy series Who Do You Think You Are? in which she found out it was a different Louis Volant who won the Legion of Honour. When she heard her grandfather's story of bravery and discovered that the War Cross was for "ordinary" soldiers like her grandfather, who had been a waiter, she stated the War Cross was "better" to her than the Legion of Honour.[33][34]

Childhood

Rowling's sister Dianne[7] was born at their home when Rowling was 23 months old.[26] When Rowling was four, the family moved to the nearby village of Winterbourne on the northern fringe of Bristol.[35] As a child, Rowling often wrote fantasy stories which she frequently read to her sister.[1] Aged nine, Rowling moved to Church Cottage in the Gloucestershire village of Tutshill, close to Chepstow, Wales.[26] When she was a young teenager, her great-aunt gave her a copy of Jessica Mitford's autobiography, Hons and Rebels.[36] Mitford became Rowling's heroine, and Rowling read all of her books.[37]

Rowling has said that her teenage years were unhappy.[27] Her home life was complicated by her mother's diagnosis with multiple sclerosis[38] and a strained relationship with her father, with whom she is not on speaking terms.[27] Rowling later said that she based the character of Hermione Granger on herself when she was eleven.[39] Sean Harris, her best friend in the Upper Sixth, owned a turquoise Ford Anglia which she says inspired a flying version that appeared in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.[40] Like many teenagers, she became interested in rock music, listening to the Clash,[41] the Smiths, and Siouxsie Sioux, adopting the look of the latter with back-combed hair and black eyeliner, a look that she still sported when beginning university.[29]

Education

As a child, Rowling attended St Michael's Primary School, a school founded by abolitionist William Wilberforce and education reformer Hannah More.[42][43] Her headmaster at St Michael's, Alfred Dunn, has been suggested as the inspiration for the Harry Potter headmaster Albus Dumbledore.[44] She attended secondary school at Wyedean School and College, where her mother worked in the science department.[28] Steve Eddy, her first secondary school English teacher, remembers her as "not exceptional" but "one of a group of girls who were bright, and quite good at English".[27] Rowling took A-levels in English, French and German, achieving two As and a B[45] and was head girl.[27]

Rowling earned a BA in French and Classics at the University of Exeter.[46][47][48] Martin Sorrell, a French professor at Exeter, remembers "a quietly competent student, with a denim jacket and dark hair, who, in academic terms, gave the appearance of doing what was necessary".[27] Rowling recalls doing little work, preferring to read Dickens and Tolkien.[27] After a year of study in Paris, Rowling graduated from Exeter in 1986.[27] In 1988, Rowling wrote a short essay about her time studying Classics titled "What was the Name of that Nymph Again? or Greek and Roman Studies Recalled"; it was published by the University of Exeter's journal Pegasus.[49]

Inspiration and mother's death

Rowling worked as a researcher and bilingual secretary in London for Amnesty International,[50] then moved with her boyfriend to Manchester[26] where she worked at the Chamber of Commerce.[29] In 1990, she was on a four-hour delayed train trip from Manchester to London when the idea "came fully formed" into her mind for a story of a young boy attending a school of wizardry.[26][51] When she reached her Clapham Junction flat, she began to write immediately.[26][52]

In December 1990, Rowling's mother Anne died after suffering from multiple sclerosis for ten years.[26] Rowling was writing Harry Potter at the time and had never told her mother about it.[20] Her mother's death heavily affected Rowling's writing,[20] and she channelled her own feelings of loss by writing about Harry's grief in greater detail in the first book.[53]

Marriage, divorce, and single parenthood

An advertisement in The Guardian[29] led Rowling to move to Porto, Portugal, to teach English as a foreign language.[7][37] She taught at night and began writing in the day while listening to Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto.[27] After 18 months in Porto, she met Portuguese television journalist Jorge Arantes in a bar, and found that they shared an interest in Jane Austen.[29] They married on 16 October 1992, and daughter Jessica Isabel Rowling Arantes (named after Jessica Mitford) was born on 27 July 1993 in Portugal.[29] She had previously suffered a miscarriage.[29] The couple separated on 17 November 1993.[29][54] Biographers have suggested that Rowling suffered domestic abuse during her marriage,[29][55] which Rowling later confirmed;[56] Arantes stated in an article for The Sun in June 2020 that he had slapped her and did not regret it.[57] United Kingdom domestic abuse commissioner Nicole Jacobs formally advised The Sun that it was unacceptable "to repeat and magnify the voice of someone who openly admits to violence against a partner".[58] In December 1993, with three chapters of Harry Potter in her suitcase,[27] Rowling and her daughter moved to Edinburgh, Scotland, to be near Rowling's sister.[26]

Seven years after graduating from university, Rowling saw herself as a failure.[59] Her marriage had failed, and she was jobless with a dependent child, but she described her failure as "liberating" and allowing her to focus on writing.[59] During this period, she was diagnosed with clinical depression and contemplated suicide.[60] Her depression inspired the characters known as Dementors, soul-sucking creatures introduced in the third book.[61] Rowling signed up for welfare benefits, describing her economic status as being "poor as it is possible to be in modern Britain, without being homeless".[27][59]

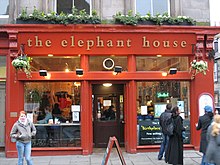

Rowling was left in despair after her estranged husband arrived in Scotland, seeking both her and their daughter.[29] She obtained an Order of Restraint, and Arantes returned to Portugal, with Rowling filing for divorce in August 1994.[29] She began a teacher training course in August 1995 at the Moray House School of Education at Edinburgh University,[62] after completing her first novel while living on state benefits.[63] She wrote in many cafés, especially Nicolson's Café (owned by her brother-in-law)[64][65] and the Elephant House,[66] wherever she could get Jessica to fall asleep.[26][67] In a 2001 BBC interview, Rowling denied the rumour that she wrote in local cafés to escape from her unheated flat, pointing out that it had heating. She stated that she wrote in cafés because coffee was available without her breaking the flow of writing, and that taking her baby out for a walk helped her to fall asleep.[67][68]

Harry Potter

In 1995, Rowling finished her manuscript for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone which was typed on an old manual typewriter.[70] Upon the enthusiastic response of Bryony Evens, a reader who had been asked to review the book's first three chapters, the Fulham-based Christopher Little Literary Agency agreed to represent Rowling in her quest for a publisher. The book was submitted to twelve publishing houses, all of which rejected the manuscript.[29] A year later, she was finally given the green light (and a £1,500 advance) by editor Barry Cunningham from Bloomsbury, a publishing house in London.[29][71] The decision to publish Rowling's book owes much to Alice Newton, the eight-year-old daughter of Bloomsbury's chairman, who was given the first chapter to review by her father and immediately demanded the next.[72] Although Bloomsbury agreed to publish the book, Cunningham says that he advised Rowling to get a day job, since she had little chance of making money in children's books.[73] Soon after, in 1997, Rowling received an £8,000 grant from the Scottish Arts Council to enable her to continue writing.[74]

In June 1997, Bloomsbury published Philosopher's Stone with an initial print run of 1,000 copies, 500 of which were distributed to libraries. Today, such copies are valued between £16,000 and £25,000.[75] Five months later, the book won its first award, a Nestlé Smarties Book Prize. In February 1998, the novel won the British Book Award for Children's Book of the Year and, later, the Children's Book Award. In early 1998, an auction was held in the United States for the rights to publish the novel, and was won by Scholastic Inc., for US$105,000. Rowling said that she "nearly died" when she heard the news.[76] In October 1998, Scholastic published Philosopher's Stone in the US under the title of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, a change Rowling says she now regrets and would have fought if she had been in a better position at the time.[77] Rowling moved from her flat with the money from the Scholastic sale, into 19 Hazelbank Terrace in Edinburgh.[64]

Its sequel, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, was published in July 1998 and again Rowling won the Smarties Prize.[78] In December 1999, the third novel, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, won the Smarties Prize, making Rowling the first person to win the award three times running.[79] She later withdrew the fourth Harry Potter novel from contention to allow other books a fair chance. In January 2000, Prisoner of Azkaban won the inaugural Whitbread Children's Book of the Year award, though it lost the Book of the Year prize to Seamus Heaney's translation of Beowulf.[80]

The fourth book, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, was released simultaneously in the UK and the US on 8 July 2000 and broke sales records in both countries, with 372,775 copies of the book sold in its first day in the UK, almost equalling the number Prisoner of Azkaban sold during its first year.[81] In the US, the book sold three million copies in its first 48 hours, smashing all records.[81] Rowling said that she had had a crisis while writing the novel and had to rewrite one chapter many times to fix a problem with the plot.[82] Rowling was named Author of the Year in the 2000 British Book Awards.[83]

A wait of three years occurred between the release of Goblet of Fire and the fifth Harry Potter novel, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. This gap led to press speculation that Rowling had developed writer's block, speculations she later denied.[84] Rowling later said that writing the book was a chore, that it could have been shorter, and that she ran out of time and energy as she tried to finish it.[85]

The sixth book, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, was released on 16 July 2005. It too broke all sales records, selling nine million copies in its first 24 hours of release.[86] In 2006, Half-Blood Prince received the Book of the Year prize at the British Book Awards.[78]

The title of the seventh and final Harry Potter book was announced on 21 December 2006 as Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[87] In February 2007, it was reported that Rowling wrote on a bust in her hotel room at the Balmoral Hotel in Edinburgh that she had finished the seventh book in that room on 11 January 2007.[88] Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was released on 21 July 2007 (0:01 BST)[89] and broke its predecessor's record as the fastest-selling book of all time.[90] It sold 11 million copies in the first day of release in the United Kingdom and United States.[90] The book's last chapter was one of the earliest things she wrote in the entire series.[91]

The last four Harry Potter books have consecutively set records as the fastest-selling books in history.[90][92] The series, totalling 4,195 pages,[93] has been translated, in whole or in part, into 65 languages.[94]

The Harry Potter books have also gained recognition for sparking an interest in reading among the young at a time when children were thought to be abandoning books for computers, television and video games,[95] although it is reported that despite the huge uptake of the books, adolescent reading has continued to decline.[96]

Harry Potter films

In October 1998, Warner Bros. purchased the film rights to the first two novels for a seven-figure sum.[97] A film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone was released on 16 November 2001, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets on 15 November 2002.[98] Both films were directed by Chris Columbus. The film version of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was released on 4 June 2004, directed by Alfonso Cuarón. The fourth film, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, was directed by Mike Newell, and released on 18 November 2005. The film of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix was released on 11 July 2007.[98] David Yates directed, and Michael Goldenberg wrote the screenplay, having taken over the position from Steve Kloves. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was released on 15 July 2009.[99] David Yates directed again, and Kloves returned to write the script.[100] Warner Bros. filmed the final instalment of the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, in two segments, with part one being released on 19 November 2010 and part two being released on 15 July 2011. Yates directed both films.[101][102]

Warner Bros. took considerable notice of Rowling's desires when drafting her contract. One of her principal stipulations was the films be shot in Britain with an all-British cast,[103] which has been generally adhered to. Rowling also demanded that Coca-Cola, the winner in the race to tie in their products to the film series, donate US$18 million to the American charity Reading Is Fundamental, as well as several community charity programmes.[104]

Steve Kloves wrote the screenplays for all but the fifth film; Rowling assisted him in the writing process, ensuring that his scripts did not contradict future books in the series.[105] She told Alan Rickman (Severus Snape) and Robbie Coltrane (Hagrid) certain secrets about their characters before they were revealed in the books.[106] Daniel Radcliffe (Harry Potter) asked her if Harry died at any point in the series; Rowling answered him by saying, "You have a death scene", thereby not explicitly answering the question.[107] Director Steven Spielberg was approached to direct the first film, but dropped out. The press has repeatedly claimed that Rowling played a role in his departure, but Rowling stated that she had no say in who directed the films and would not have vetoed Spielberg.[108] Rowling's first choice for the director had been Monty Python member Terry Gilliam, but Warner Bros. wanted a family-friendly film and chose Columbus.[109]

Rowling had gained some creative control over the films, reviewing all the scripts[110] as well as acting as a producer on the final two-part instalment, Deathly Hallows.[111]

Rowling, producers David Heyman and David Barron, along with directors David Yates, Mike Newell and Alfonso Cuarón collected the Michael Balcon Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema at the 2011 British Academy Film Awards in honour of the Harry Potter film franchise.[112]

In September 2013, Warner Bros. announced an "expanded creative partnership" with Rowling, based on a planned series of films about her character Newt Scamander, author of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. The first film was released in November 2016 and is set roughly 70 years before the events of the main series.[113] In 2016, it was announced that the series would consist of five films. The second, Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, was released in November 2018.[114] The third, Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore is scheduled to be released on 15 April 2022.[115]

Financial success

In 2004, Forbes named Rowling as the first person to become a US-dollar billionaire by writing books,[116] the second-richest female entertainer and the 1,062nd richest person in the world.[117][118] Rowling disputed the calculations and said she had plenty of money, but was not a billionaire.[11] The 2021 Sunday Times Rich List estimated Rowling's fortune at £820 million, ranking her as the 196th richest person in the UK.[14] After spending eight years on the list, in 2012 Forbes removed Rowling from their rich list, claiming that her US$160 million in charitable donations and the high tax rate in the UK meant she was no longer a billionaire.[119] In February 2013, she was assessed as the 13th most powerful woman in the United Kingdom by Woman's Hour on BBC Radio 4.[120]

Rowling acquired the courtesy title of Laird of Killiechassie in 2001 when she purchased the historic Killiechassie House, and its surrounding estate situated on the banks of the River Tay, near Aberfeldy, in Perth and Kinross.[121][122] Rowling also owns a £4.5 million Georgian house in Kensington, west London, on a street with 24-hour security.[123]

Rowling has consistently been ranked among the highest earning authors in the world.[124] She was named the world's highest paid author in 2017 and 2019 by Forbes with net earnings of £72 million ($95 million) and $92 million respectively.[125][126]

Remarriage and family

On 26 December 2001, Rowling married Neil Murray (born 30 June 1971), a Scottish doctor,[127] in a private ceremony at her home, Killiechassie House, in Scotland.[128] Their son, David Gordon Rowling Murray, was born on 24 March 2003.[129] Shortly after Rowling began writing Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, she ceased working on the novel to care for David in his early infancy.[130]

Rowling is a friend of Sarah Brown, wife of former prime minister Gordon Brown, whom she met when they collaborated on a charitable project. When Sarah Brown's son Fraser was born in 2003, Rowling was one of the first to visit her in hospital.[131] Rowling's youngest child, daughter Mackenzie Jean Rowling Murray, to whom she dedicated Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, was born on 23 January 2005.[132]

In October 2012, a New Yorker magazine article stated that the Rowling family lived in a seventeenth-century Edinburgh house, concealed at the front by tall conifer hedges. Prior to October 2012, Rowling lived near the author Ian Rankin, who later said she was quiet and introspective, and that she seemed in her element with children.[27][133] As of June 2014, the family resides in Scotland.[134]

The Casual Vacancy

In July 2011, Rowling parted company with her agent, Christopher Little, moving to a new agency founded by one of his staff, Neil Blair.[27][135] On 23 February 2012, his agency, the Blair Partnership, announced on its website that Rowling was set to publish a new book targeted at adults. In a press release, Rowling said that her new book would be quite different from Harry Potter. In April 2012, Little, Brown and Company announced that the book was titled The Casual Vacancy and would be released on 27 September 2012.[136] Rowling gave several interviews and made appearances to promote The Casual Vacancy, including at the London Southbank Centre,[137] the Cheltenham Literature Festival,[138] Charlie Rose[139] and the Lennoxlove Book Festival.[140] In its first three weeks of release, The Casual Vacancy sold over 1 million copies worldwide.[141]

On 3 December 2012, it was announced that the BBC would be adapting The Casual Vacancy into a television drama miniseries. Rowling's agent, Neil Blair, acted as producer through his independent production company and with Rick Senat serving as executive producer. Rowling collaborated on the adaptation, serving as an executive producer for the series. The series aired in three parts from 15 February to 1 March 2015.[142][143]

Cormoran Strike

In 2007, during the Edinburgh Book Festival, author Ian Rankin claimed that his wife spotted Rowling "scribbling away" at a detective novel in a café.[144] Rankin later retracted the story, claiming it was a joke,[145] but the rumour persisted, with a report in 2012 in The Guardian speculating that Rowling's next book would be a crime novel.[146] In an interview with Stephen Fry in 2005, Rowling had claimed that she would much prefer to write any subsequent books under a pseudonym, but had previously conceded to Jeremy Paxman in 2003 that if she did, the press would probably "find out in seconds".[147]

In April 2013, Little Brown published The Cuckoo's Calling, the purported début novel of author Robert Galbraith, whom the publisher described as "a former plainclothes Royal Military Police investigator who had left in 2003 to work in the civilian security industry".[148] The novel, a detective story in which private investigator Cormoran Strike unravels the supposed suicide of a supermodel, sold 1,500 copies in hardback (although the matter was not resolved as of 21 July 2013; later reports stated that this number is the number of copies that were printed for the first run, while the sales total was closer to 500)[149] and received acclaim from other crime writers[148] and critics[150]—a Publishers Weekly review called the book a "stellar debut",[151] while the Library Journal's mystery section pronounced the novel "the debut of the month".[152]

India Knight, a novelist and columnist for The Sunday Times, tweeted on 9 July 2013 that she had been reading The Cuckoo's Calling and thought it was good for a début novel. In response, a tweeter called Jude Callegari said that the author was Rowling. Knight queried this but got no further reply.[153] Knight notified Richard Brooks, arts editor of The Sunday Times, who began his own investigation.[153][154] After discovering that Rowling and Galbraith had the same agent and editor, he sent the books for linguistic analysis which found similarities, and subsequently contacted Rowling's agent who confirmed it was Rowling's pseudonym.[154] Within days of Rowling being revealed as the author, sales of the book rose by 4,000%,[153] and Little Brown printed another 140,000 copies to meet the increase in demand.[155] As of 18 July 2013, a signed copy of the first edition sold for US$4,453 (£2,950), while an unsold signed first-edition copy was being offered for $6,188 (£3,950).[149]

Rowling said that she had enjoyed working under a pseudonym.[156] On her Robert Galbraith website, Rowling explained that she took the name from one of her personal heroes, Robert F. Kennedy, and a childhood fantasy name she had invented for herself, Ella Galbraith.[157] Commenting on the choice of the name in an interview with Graham Norton, she remarked that, "when I was unmasked – when I was outed – people analysed the name as 'Robert means a bright shining fame and Galbraith means stranger' and I was thinking 'really? I had no idea!' But, you know, things get over analysed sometimes."[158]

Soon after the revelation, Brooks pondered whether Jude Callegari could have been Rowling, as part of wider speculation that the entire affair had been a publicity stunt. Some also observed that many of the writers who had initially praised the book, such as Alex Gray or Val McDermid,[159] were within Rowling's circle of acquaintances; both vociferously denied any foreknowledge of Rowling's authorship.[153] Judith "Jude" Callegari was the best friend of the wife of Chris Gossage, a partner within Russells Solicitors, Rowling's legal representatives.[160][161] Rowling released a statement saying she was disappointed and angry;[160] Russells apologised for the leak, confirming it was not part of a marketing stunt and that "the disclosure was made in confidence to someone he trusted implicitly".[155] Russells made a donation to the Soldiers' Charity on Rowling's behalf and reimbursed her for her legal fees.[162] On 26 November 2013, the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) issued Gossage a written rebuke and a £1,000 fine for breaching privacy rules.[163]

On 17 February 2014, Rowling announced that the second Cormoran Strike novel, named The Silkworm, would be released in June 2014. It sees Strike investigating the disappearance of a writer hated by many of his old friends for insulting them in his new novel.[164]

In 2015, Rowling stated on Galbraith's website that the third Cormoran Strike novel would include "an insane amount of planning, the most I have done for any book I have written so far. I have colour-coded spreadsheets so I can keep a track of where I am going."[165] On 24 April 2015, Rowling announced that work on the third book was completed. Titled Career of Evil, it was released on 20 October 2015 in the United States, and on 22 October 2015 in the United Kingdom.[166]

In 2017, the BBC released a Cormoran Strike television series, starring Tom Burke as Cormoran Strike.The series was subsequently picked up by HBO for distribution in the United States and Canada.[167]

In March 2017, Rowling revealed the fourth novel's title via Twitter in a game of "Hangman" with her followers. After many failed attempts, followers finally guessed correctly. Rowling confirmed that the next novel's title is Lethal White.[168] While intended for a 2017 release, Rowling tweeted the book was taking longer than expected and would be the longest book in the series thus far.[169][170] The book was released 18 September 2018.[171] The fifth novel in the series, titled Troubled Blood, was published in September 2020.[172] In May 2021, Troubled Blood won the Crime and Thriller Book of the Year at the British Book Awards.[173]

Subsequent Harry Potter publications

Rowling has said it is unlikely she will write any more books in the Harry Potter series.[174] In October 2007, she stated that her future work was unlikely to be in the fantasy genre.[175] On 1 October 2010, in an interview with Oprah Winfrey, Rowling stated a new book on the saga might happen.[176]

In 2007, Rowling stated that she planned to write an encyclopaedia of Harry Potter's wizarding world consisting of various unpublished material and notes.[177] Any profits from such a book would be given to charity.[178] During a news conference at Hollywood's Kodak Theatre in 2007, Rowling, when asked how the encyclopaedia was coming along, said, "It's not coming along, and I haven't started writing it. I never said it was the next thing I'd do."[179] At the end of 2007, Rowling said that the encyclopaedia could take up to ten years to complete.[180]

In June 2011, Rowling announced that future Harry Potter projects, and all electronic downloads, would be concentrated in a new website, called Pottermore.[181] The site includes 18,000 words of information on characters, places and objects in the Harry Potter universe.[182]

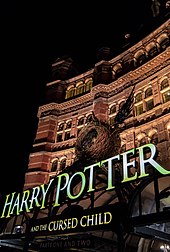

In October 2015, Rowling announced via Pottermore that a two-part play she had co-authored with playwrights Jack Thorne and John Tiffany, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, was the "eighth Harry Potter story" and that it would focus on the life of Harry Potter's youngest son Albus after the epilogue of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[183] On 28 October 2015, the first round of tickets went on sale and sold out in several hours.[184]

The Ickabog

Starting on 26 May 2020 and running until 10 July 2020, Rowling published a new children's story online. The Ickabog was first mooted as a "political fairytale" for children in a 2007 Time magazine interview. Rowling shelved the story and decided to publish it for children as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. A print edition was released on 10 November 2020[185] and contains illustrations selected from entries to a competition running concurrently with the online publication.[9] Rowling stated that all royalties from the book would be donated to charities helping groups strongly impacted by COVID-19.[186]

The Christmas Pig

On 13 April 2021, it was announced that Rowling would be publishing a new children's novel, entitled The Christmas Pig, due to be released in October 2021. The story is unconnected to any of Rowling's previous works.[187] Upon release, the book received generally positive critical reviews and emerged a bestseller with high pre-sales on Amazon.[188][189][190][191][192]

Philanthropy

In 2000, Rowling established the Volant Charitable Trust, which uses its annual budget of £5.1 million to combat poverty and social inequality. The fund also gives to organisations that aid children, one-parent families, and multiple sclerosis research.[193][194]

Anti-poverty and children's welfare

Rowling, once a single parent, is now president of the charity Gingerbread (originally One Parent Families), having become their first Ambassador in 2000.[195][196] Rowling collaborated with Sarah Brown to write a book of children's stories to aid One Parent Families.[197]

In 2001, the UK anti-poverty fundraiser Comic Relief asked three best-selling British authors—cookery writer and TV presenter Delia Smith, Bridget Jones creator Helen Fielding, and Rowling—to submit booklets related to their most famous works for publication.[198] Rowling's two booklets, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and Quidditch Through the Ages, are ostensibly facsimiles of books found in the Hogwarts library. Since going on sale in March 2001, the books have raised £15.7 million for the fund. The £10.8 million they have raised outside the UK have been channelled into a newly created International Fund for Children and Young People in Crisis.[199] In 2002, Rowling contributed a foreword to Magic, an anthology of fiction published by Bloomsbury Publishing, helping to raise money for the National Council for One Parent Families.[200]

In 2005, Rowling and MEP Emma Nicholson founded the Children's High Level Group (now Lumos).[201] In January 2006, Rowling went to Bucharest to highlight the use of caged beds in mental institutions for children.[202] To further support the CHLG, Rowling auctioned one of seven handwritten and illustrated copies of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, a series of fairy tales referred to in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. The book was purchased for £1.95 million by online bookseller Amazon.com on 13 December 2007, becoming the most expensive modern book ever sold at auction.[203][204] Rowling gave away the remaining six copies to those who have a close connection with the Harry Potter books.[203] In 2008, Rowling agreed to publish the book with the proceeds going to Lumos.[133] On 1 June 2010 (International Children's Day), Lumos launched an annual initiative—Light a Birthday Candle for Lumos.[205] In November 2013, Rowling handed over all earnings from the sale of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, totalling nearly £19 million.[206]

In July 2012, Rowling was featured at the 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony in London, where she read a few lines from J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan as part of a tribute to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. An inflatable representation of Lord Voldemort and other children's literary characters accompanied her reading.[207]

Multiple sclerosis

Rowling has contributed money and support for research and treatment of multiple sclerosis, from which her mother suffered before her death in 1990. In 2006, Rowling contributed a substantial sum toward the creation of a new Centre for Regenerative Medicine at Edinburgh University, later named the Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic.[208] In 2010, she donated another £10 million to the centre,[209] and in 2019 a further £15 million.[210] For unknown reasons, Scotland, Rowling's country of adoption, has the highest rate of multiple sclerosis in the world. In 2003, Rowling took part in a campaign to establish a national standard of care for MS sufferers.[211] In April 2009, she announced that she was withdrawing her support for Multiple Sclerosis Society Scotland, citing her inability to resolve an ongoing feud between the organisation's northern and southern branches that had sapped morale and led to several resignations.[211]

COVID-19

In May 2020, Rowling announced the publication of children's novel The Ickabog, with all author royalties being donated to charities supporting those affected by COVID-19. Rowling organised a drawing competition via Twitter, where children from all over the world could draw and submit illustrations for the book as they were reading it in instalments. These illustrations were then published in various editions of the book once it was fully released. According to Rowling in a 2020 BBC Radio 2 interview with Graham Norton, there were over 60,000 entries to the competition.[212] Through the Volant Charitable Trust, Rowling donated six-figure sums to both Khalsa Aid and the British Asian Trust to support their covid-relief work in India, in May 2021.[213]

Other philanthropic work

In May 2008, bookseller Waterstones asked Rowling and 12 other writers (Lisa Appignanesi, Margaret Atwood, Lauren Child, Sebastian Faulks, Richard Ford, Neil Gaiman, Nick Hornby, Doris Lessing, Michael Rosen, Axel Scheffler, Tom Stoppard and Irvine Welsh) to compose a short piece of their own choosing on a single A5 card, which would then be sold at auction in aid of the charities Dyslexia Action and English PEN. Rowling's contribution was an 800-word Harry Potter prequel that concerns Harry's father, James Potter, and godfather, Sirius Black, and takes place three years before Harry was born. The cards were collated and sold for charity in book form in August 2008.[214]

On 1 and 2 August 2006, she read alongside Stephen King and John Irving at Radio City Music Hall in New York City. Profits from the event were donated to the Haven Foundation, a charity that aids artists and performers left uninsurable and unable to work, and the medical NGO Médecins Sans Frontières.[215] In May 2007, Rowling pledged a donation reported as over £250,000 to a reward fund started by the tabloid News of the World for the safe return of a young British girl, Madeleine McCann, who disappeared in Portugal.[216] Rowling, along with Nelson Mandela, Al Gore, and Alan Greenspan, wrote an introduction to a collection of Gordon Brown's speeches, the proceeds of which were donated to the Jennifer Brown Research Laboratory.[217] After her exposure as the true author of The Cuckoo's Calling led to a massive increase in sales, Rowling announced she would donate all her royalties to the Army Benevolent Fund, claiming she had always intended to but never expected the book to be a best-seller.[218]

Rowling is a member of both English PEN and Scottish PEN. She was one of 50 authors to contribute to First Editions, Second Thoughts, a charity auction for English PEN. Each author hand annotated a first-edition copy of one of their books, in Rowling's case, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. The book was the highest-selling lot of the event and fetched £150,000 ($228,600).[219]

Rowling is a supporter of the Shannon Trust, which runs the Toe by Toe Reading Plan and the Shannon Reading Plan in prisons across Britain, helping and giving tutoring to prisoners who cannot read.[220]

Influences

Rowling has named civil rights activist Jessica Mitford as her greatest influence. She said "Jessica Mitford has been my heroine since I was 14 years old, when I overheard my formidable great-aunt discussing how Mitford had run away at the age of 19 to fight with the Reds in the Spanish Civil War", and claims what inspired her about Mitford was that she was "incurably and instinctively rebellious, brave, adventurous, funny and irreverent, she liked nothing better than a good fight, preferably against a pompous and hypocritical target".[36] Rowling has described Jane Austen as her favourite author,[221] calling Emma her favourite book in O, The Oprah Magazine.[222] As a child, Rowling has said her early influences included The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis, The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge, and Manxmouse by Paul Gallico.[223]

Views

Politics

To many, Rowling is known for her centre-left political views. In September 2008, on the eve of the Labour Party Conference, Rowling announced that she had donated £1 million to the Labour Party, and publicly endorsed Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown over Conservative challenger David Cameron, praising Labour's policies on child poverty.[224] Rowling is a close friend of Sarah Brown, wife of Gordon Brown, whom she met when they collaborated on a charitable project for One Parent Families.[131]

Rowling commented on American politics when she discussed the 2008 United States presidential election with the Spanish-language newspaper El País in February 2008, stating that the election would have a profound effect on the rest of the world. She also said that Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton would be "extraordinary" in the White House. In the same interview, Rowling identified Robert F. Kennedy as her hero.[225]

In April 2010, an article by Rowling was published in The Times, in which she criticised then Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron's plan to encourage married couples to stay together by offering them a £150 annual tax credit: "Nobody who has ever experienced the reality of poverty could say 'it's not the money, it's the message'. When your flat has been broken into, and you cannot afford a locksmith, it is the money. When you are two pence short of a tin of baked beans, and your child is hungry, it is the money. When you find yourself contemplating shoplifting to get nappies, it is the money."[226]

Due to her residency in Scotland, Rowling was eligible to vote in the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, during the run-up to which she campaigned for the "No" vote.[227] She donated £1 million to the Better Together anti-independence campaign run by her former neighbour Alistair Darling,[134] the largest donation it had received at the time. In a blog post, Rowling explained that an open letter from Scottish medical professionals raised problems with First Minister Alex Salmond's plans for a common research funding.[134] Rowling compared some Scottish Nationalists with the Death Eaters, characters from Harry Potter who are scornful of those without pure blood.[228]

On 22 October 2015, a letter was published in The Guardian signed by Rowling (along with over 150 other figures from arts and politics) opposing the cultural boycott of Israel, and announcing the creation of a network for dialogue, called Culture for Coexistence.[229] Rowling later explained her position in greater detail, stating that although she opposed most of Benjamin Netanyahu's actions, she did not believe the cultural boycott would bring about the removal of Israel's leader or the improvement of the situation in Israel and Palestine.[230]

In June 2016, Rowling campaigned for the United Kingdom to stay in the European Union in the run-up to the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, stating on her website that, "I'm the mongrel product of this European continent and I'm an internationalist. I was raised by a Francophile mother whose family was proud of their part-French heritage ... My values are not contained or proscribed by borders. The absence of a visa when I cross the channel has symbolic value to me. I might not be in my house, but I'm still in my hometown."[231] Rowling expressed concern that "racists and bigots" were directing parts of the Leave campaign. In a blog post, she added: "How can a retreat into selfish and insecure individualism be the right response when Europe faces genuine threats, when the bonds that tie us are so powerful, when we have come so far together? How can we hope to conquer the enormous challenges of terrorism and climate change without cooperation and collaboration?"[232]

Religion

Some religious people, figures and organisations have, over the years, objected to and decried Rowling's books for the perceived promotion of witchcraft. Many objections have come from Christians in particular, though Rowling herself has stated that she identifies as a Christian,[233] stating that "I believe in God, not magic."[234] Early on in writing the Harry Potter series of books and in response to criticism, Rowling did not disclose her religious beliefs, feeling that if readers knew of her religious views, they would be able to predict plot lines of characters in her books.[235]

In 2007, Rowling stated that she was the only person in her family who attended church regularly, and that she was an adherent of the Church of England. As a student, she had previously been annoyed at the "smugness of religious people", and had attended less often. Later, she began attending a Church of Scotland congregation around the time she was writing Harry Potter.[236][237] Her eldest daughter, Jessica, was baptised there.[233]

In a 2006 interview with Tatler, Rowling noted that, "like Graham Greene, my faith is sometimes about if my faith will return. It's important to me."[20] She has said that she has struggled with doubt, that she believes in an afterlife,[238] and that her faith plays a part in her books.[239][240][241] In a 2012 radio interview, Rowling stated that she was a member of the Scottish Episcopal Church, a province of the Anglican Communion.[242]

In 2015, following the referendum on same-sex marriage in Ireland, Rowling joked that if Ireland legalised same-sex marriage, Dumbledore and Gandalf could get married there.[243] The Westboro Baptist Church, in response, stated that if the two got married, they would picket. Rowling responded by saying, "Alas, the sheer awesomeness of such a union in such a place would blow your tiny bigoted minds out of your thick sloping skulls."[244]

Press

Rowling has stated that she has a difficult relationship with the press, admitting at one point to being "thin-skinned" and disliking the fickle nature of reporting, though she has disputed that she is a recluse who hates to be interviewed.[245] By 2011, Rowling had taken more than 50 actions against the press.[246] In 2001, the Press Complaints Commission upheld a complaint by Rowling over a series of unauthorised photographs of her with her daughter on the beach in Mauritius published in OK! magazine.[247] In 2007, Rowling's young son, David, assisted by Rowling and her husband, lost a court fight to ban publication of a photograph of David. The photo, which was taken by a photographer using a long-range lens, was then published in a Sunday Express article featuring Rowling's family life and motherhood.[19] The judgement was overturned in David's favour in May 2008.[248]

Rowling has expressed her particular dislike of the British tabloid Daily Mail, which has conducted several interviews with her estranged ex-husband. As one journalist noted, "Harry's Uncle Vernon is a grotesque philistine of violent tendencies and remarkably little brain. It is not difficult to guess which newspaper Rowling gives him to read [in Goblet of Fire]."[249] In 2014, she successfully sued the Mail for libel over an article about her time as a single mother.[250] Some have speculated that Rowling's fraught relationship with the press was the inspiration behind the character Rita Skeeter, a gossipy celebrity journalist who first appears in Goblet of Fire, but Rowling said in 2000 that the character's development predates her rise to fame.[251]

In September 2011, Rowling was named as a "core participant" in the Leveson Inquiry into the culture, practices and ethics of the British press, as one of dozens of celebrities who may have been the victim of phone hacking.[252] On 24 November 2011, Rowling gave evidence before the inquiry; although she was not suspected to have been the victim of phone hacking,[253] her testimony included accounts of photographers camping on her doorstep, her fiancé being duped into giving his home address to a journalist masquerading as a tax official,[253] her chasing a journalist a week after giving birth,[246] a journalist leaving a note inside her then-five-year-old daughter's schoolbag, and an attempt by The Sun to "blackmail" her into a photo opportunity in exchange for the return of a stolen manuscript.[254] Rowling claimed she had to leave her former home in Merchiston because of press intrusion.[254] In November 2012, Rowling wrote an op-ed for The Guardian in response to David Cameron's decision not to implement the full recommendations of the Leveson inquiry, stating that she felt "duped and angry".[255]

In 2014, Rowling reaffirmed her support for "Hacked Off", a campaign supporting the self-regulation of the press, by co-signing a declaration to "[safeguard] the press from political interference while also giving vital protection to the vulnerable" with other British celebrities.[256]

Transgender people

In December 2019, Rowling tweeted her support for Maya Forstater, a British woman who initially lost her employment tribunal case (Maya Forstater v Centre for Global Development) but won on appeal against her former employer, the Center for Global Development, after her contract was not renewed due to her comments about transgender people.[257][258][259]

On 6 June 2020, Rowling tweeted criticism of the phrase "people who menstruate",[260] and stated "If sex isn't real, the lived reality of women globally is erased. I know and love trans people, but erasing the concept of sex removes the ability of many to meaningfully discuss their lives."[261] Rowling's tweets were criticised by GLAAD, who called them "cruel" and "anti-trans".[262][263] Some members of the cast of the Harry Potter film series criticised Rowling's views or spoke out in support of trans rights, including Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, Rupert Grint, Bonnie Wright, and Katie Leung, as did Fantastic Beasts lead actor Eddie Redmayne and the fansites MuggleNet and The Leaky Cauldron.[264][265][266] Actress Noma Dumezweni (who played Hermione Granger in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child) initially expressed support for Rowling but backtracked following backlash.[267]

On 10 June 2020, Rowling published a 3,600-word essay on her website in response to the criticism.[268][269] Rowling again wrote that many women consider terms like "people who menstruate" to be demeaning. She said that she was a survivor of domestic abuse and sexual assault, and stated that "When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he's a woman ... then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside", while stating that most trans people were vulnerable and deserved protection.[270] Reuters reported that, in the United States, women's rights groups said in 2016 that 200 municipalities which allowed trans people to use women's shelters reported no rise in any violence as a result; they also said that excluding transgender people from facilities consistent with their gender makes them vulnerable to assault.[271] Rowling's essay was criticised by, among others, the children's charity Mermaids (who support transgender and gender non-conforming children and their parents), Stonewall, GLAAD and the feminist gender theorist Judith Butler.[272][273][274][275][276][277] Rowling has been referred to as a trans-exclusionary radical feminist (TERF) on multiple occasions, though she rejects the label.[278] Rowling has received support from actors Robbie Coltrane,[279] Brian Cox,[280] and Eddie Izzard,[281] and some feminists,[282] such as activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali[283] and radical feminist Julie Bindel.[282] The essay was nominated by the BBC for their annual Russell Prize for best writing.[284][285]

In August 2020, Rowling returned her Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Ripple of Hope Award after Kerry Kennedy released a statement expressing her "profound disappointment" in Rowling's "attacks upon the transgender community", which Kennedy called "inconsistent with the fundamental beliefs and values of RFK Human Rights and ... a repudiation of my father's vision".[286][287][288] Rowling stated that she was "deeply saddened" by Kennedy's statement, but maintained that no award would encourage her to "forfeit the right to follow the dictates" of her conscience.[286]

Legal disputes

Rowling, her publishers, and Time Warner, the owner of the rights to the Harry Potter films, have taken legal action on many occasions to protect their copyright. The worldwide popularity of the Harry Potter series has led to the appearance of a number of locally produced, unauthorised sequels and other derivative works, sparking efforts to ban or contain them.[289]

Another area of legal dispute involves a series of injunctions obtained by Rowling and her publishers to prohibit anyone from reading her books before their official release date.[290] The injunction drew fire from civil liberties and free speech campaigners and sparked debates over the "right to read".[291][292]

Awards and honours

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled . (Discuss) (December 2021) |

Rowling has received honorary degrees from the University of St Andrews, the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Napier University, the University of Exeter (which she attended),[293] the University of Aberdeen,[294][295] and Harvard University, where she spoke at the 2008 commencement ceremony.[296] In 2009, Rowling was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur by French President Nicolas Sarkozy.[33] In 2002, Rowling became an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (HonFRSE)[297] as well a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (FRSL).[298] She was furthermore recognized as Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (FRCPE) in 2011 for services to Literature and Philanthropy.[299]

Other awards include:[78]

- 1997: Nestlé Smarties Book Prize, Gold Award for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone

- 1998: Nestlé Smarties Book Prize, Gold Award for Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

- 1998: British Children's Book of the Year, winner Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone

- 1999: Nestlé Smarties Book Prize, Gold Award for Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

- 1999: National Book Awards Children's Book of the Year, winner Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

- 1999: Whitbread Children's Book of the Year, winner Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

- 2000: British Book Awards, Author of the Year[83]

- 2000: Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), for services to Children's Literature[300]

- 2000: Locus Award, winner Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

- 2001: Hugo Award for Best Novel, winner Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

- 2003: Premio Príncipe de Asturias, Concord

- 2003: Bram Stoker Award for Best Work for Young Readers, winner Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix

- 2006: British Book Awards Book of the Year, winner for Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince

- 2007: Blue Peter Badge, Gold

- 2007: Named Barbara Walters' Most Fascinating Person of the year[301]

- 2008: British Book Awards, Outstanding Achievement

- 2008: The Edinburgh Award[302]

- 2010: Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award, inaugural award winner.[303]

- 2011: British Academy Film Awards, Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema for the Harry Potter film series, shared with David Heyman, cast and crew.[304]

- 2012: Freedom of the City of London

- 2012: Rowling was among the British cultural icons selected by artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his most famous artwork—the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover—to celebrate the British cultural figures of his life.[305]

- 2017: Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) at the 2017 Birthday Honours for services to literature and philanthropy.[306]

- 2018: Tony Award for Best Play for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child as part of the team of the Harry Potter Theatrical Productions.[307][308]

- 2019: For their first match of March 2019, the women of the United States women's national soccer team each wore a jersey with the name of a woman they were honoring on the back; Rose Lavelle chose the name of Rowling.[309]

- 2021: British Book Awards Crime and Thriller Award, winner for Troubled Blood.[173]

Publications

Children

- The Ickabog (10 November 2020)[310][311]

- The Christmas Pig (12 October 2021)[312]

Young adults

Harry Potter series

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (26 June 1997)

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2 July 1998)

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (8 July 1999)

- Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (8 July 2000)

- Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (21 June 2003)

- Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (16 July 2005)

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (21 July 2007)

Related works

- Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (supplement to the Harry Potter series) (1 March 2001)

- Quidditch Through the Ages (supplement to the Harry Potter series) (1 March 2001)

- Harry Potter prequel (short story) (July 2008)

- The Tales of Beedle the Bard (supplement to the Harry Potter series) (4 December 2008)

- Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (story concept) (31 July 2016)

- Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists (6 September 2016)

- Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies (6 September 2016)

- Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide (6 September 2016)

- Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (Original Screenplay) (19 November 2016)

- Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald (Original Screenplay) (16 November 2018)

Adults

- The Casual Vacancy (27 September 2012)

Cormoran Strike series (as Robert Galbraith)

- The Cuckoo's Calling (18 April 2013)

- The Silkworm (19 June 2014)

- Career of Evil (20 October 2015)

- Lethal White (18 September 2018)

- Troubled Blood (15 September 2020)

Other

Non-fiction

- McNeil, Gil and Brown, Sarah, editors (2002). Foreword to the anthology Magic. Bloomsbury.

- Brown, Gordon (2006). Introduction to "Ending Child Poverty" in Moving Britain Forward. Selected Speeches 1997–2006. Bloomsbury.

- Sussman, Peter Y., editor (26 July 2006). "The First It Girl: J. K. Rowling reviews Decca: the Letters by Jessica Mitford". The Daily Telegraph.

- Anelli, Melissa (2008). Foreword to Harry, A History. Pocket Books.

- Rowling, J. K. (5 June 2008). "The Fringe Benefits of Failure, and the Importance of Imagination". Harvard Magazine.

- Rowling, J. K. Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and Importance of Imagination, illustrated by Joel Holland, Sphere, 14 April 2015, 80 pages (ISBN 978-1-4087-0678-7).

- Rowling, J. K. (30 April 2009). "Gordon Brown – The 2009 Time 100". Time magazine.

- Rowling, J. K. (14 April 2010). "The Single Mother's Manifesto". The Times.

- Rowling, J. K. (30 November 2012). "I feel duped and angry at David Cameron's reaction to Leveson". The Guardian.

- Rowling, J. K. (17 December 2014). "Isn't it time we left orphanages to fairytales?" The Guardian.

- Rowling, J. K. (guest editor) (28 April 2014). "Woman's Hour Takeover". Woman's Hour, BBC Radio 4.[313]

- Rowling, J. K. (contributor) (31 October 2019) "A Love Letter to Europe".[314]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Credited as | Notes | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actress | Screenwriter | Producer | Executive producer | ||||

| 2003 | The Simpsons | Yes | Voice cameo in "The Regina Monologues" | ||||

| 2010 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 | Yes | Film based on her novel Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows | [111] | |||

| 2011 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | Yes | |||||

| 2015 | The Casual Vacancy | Yes | Television miniseries based on her novel The Casual Vacancy | [315] | |||

| 2016 | Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | Yes | Yes | Film inspired by her Harry Potter supplementary book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | [113] | ||

| 2017–present | Strike | Yes | Television series based on her Cormoran Strike novels | [316] | |||

| 2018 | Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald | Yes | Yes | Film inspired by her Harry Potter supplementary book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | [317] | ||

References

- ^ a b Rowling, J.K. (16 February 2007). "The Not Especially Fascinating Life So Far of J.K. Rowling" Archived 30 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Accio Quote (accio-quote.org). Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ^ Eyre, Charlotte (1 February 2018). "Harry Potter book sales top 500 million worldwide". The Bookseller. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018.

- ^ "500 million Harry Potter books sold worldwide". Pottermore. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "Record for best-selling book series". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Billington, Alex (9 December 2010). "Exclusive Video Interview: 'Harry Potter' Producer David Heyman". firstshowing.net. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Pictures Worldwide Satellite Trailer Debut: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1". Businesswire. 2010. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Shapiro, Marc (2000). J.K. Rowling: The Wizard Behind Harry Potter. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-32586-2. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Writing – J.K. Rowling". JK Rowling. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ a b "JK Rowling unveils The Ickabog, her first non-Harry Potter children's book". BBC News. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b Couric, Katie (18 July 2005). J.K. Rowling, the author with the magic touch Archived 28 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine. MSN. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Weisman, Aly (12 March 2012). "J.K. Rowling Is No Longer A Billionaire, Booted Off Forbes List". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Farr, Emma-Victoria (3 October 2012). "J.K. Rowling: Casual Vacancy tops fiction charts". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ a b "JK Rowling net worth — Sunday Times Rich List 2021". The Sunday Times.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy (19 December 2007). Person of the Year 2007: Runners-Up: J.K. Rowling Archived 21 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Time magazine. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ Pearse, Damien (11 October 2010). "Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling named Most Influential Woman in the UK". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the mystery of J K's lost initial". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Shelagh, Rogers (23 October 2000). "Interview: J.K. Rowling". This Morning. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Reprint Archived 15 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine at Accio Quote! (accio-quote.org). 28 July 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2013. - ^ a b "Judge rules against J.K. Rowling in privacy case" Archived 8 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Guardian Unlimited. 7 August 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d Greig, Geordie (10 January 2006). "There would be so much to tell her ..." Archived 14 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ "Witness statement of Joanne Kathleen Rowling" (PDF). The Leveson Inquiry. November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ "Rowling, Joanne Kathleen". Who's Who. ukwhoswho.com. 2015 (online Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ "Biography: J.K. Rowling" Archived 31 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine . Scholastic.com. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ^ "Rowling, J.K.". World Book. 2006.

- ^ Hutchinson, Lynne (6 September 2012). "Concerns raised about future of former Chipping Sodbury cottage hospital site". Gazette Series. Gloucestershire, UK. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Biography" Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine . JKRowling.com. Retrieved 17 March 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Parker, Ian (24 September 2012). "Mugglemarch: J.K. Rowling writes a realist novel for adults". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, Sean (2003), J.K. Rowling: A Biography (Michael O'Mara, London), p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The J.K. Rowling Story". The Scotsman. 16 June 2003. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "J.K. Rowling's ancestors on ScotlandsPeople". ScotlandsPeople. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Powell, Kimberly. "J.K. Rowling Family Tree". About.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ Louis François Alexandre Volant 1878–1948 on Lives of the First World War. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ a b Keaten, Jamey (3 February 2009). "France honors Harry Potter author Rowling". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ Who Do You Think You Are?, Series 8, Episode 2. BBC.

- ^ Sexton, Colleen A. (2008). J. K. Rowling. Brookfield, Conn: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8225-7949-6. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- ^ a b J. K. Rowling (26 November 2006). "The first It Girl". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ a b Fraser, Lindsey (2 November 2002). "Harry Potter – Harry and me". The Scotsman. Interview with Rowling, edited excerpt from Conversations with J.K. Rowling.

Reprint Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine at Accio Quote! (accio-quote.org). 31 May 2003; last updated 12 February 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2014. - ^ "JK Rowling discusses mother's battle with MS". Barchester. 2014. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Feldman, Roxanne (September 1999). "The Truth about Harry". School Library Journal.

Reprint Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine at Accio Quote! (accio-quote.org). Retrieved 6 December 2014. - ^ Fraser, Lindsey. Conversations with J.K. Rowling, pp. 19–20. Scholastic.

- ^ Fraser, Lindsey. Conversations with J.K. Rowling, p. 29. Scholastic.

- ^ St Michaels Register 1966–70 Archived 22 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Winterbourne. – Rowling listed as admission No. 305. Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ^ "Happy birthday J.K. Rowling – here are 10 magical facts about the 'Harry Potter' author [Updated]". Los Angeles Times. 31 July 2010. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ Kirk, Connie Ann (2003). J. K. Rowling: a biography. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-313-32205-1. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- ^ The JK Rowling story, The Scotsman, 16 June 2003, Archived from the original

- ^ Fraser, Lindsey. Conversations with J.K. Rowling, p. 34. Scholastic.

- ^ "J. K. Rowling's Education Background". EDU InReview. 10 November 2010. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Farr, Emma-Victoria (27 September 2012). "JK Rowling: 10 facts about the writer". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Rowling, J.K. (1988). "What was the Name of that Nymph Again? or Greek and Roman Studies Recalled". Pegasus. University of Exeter Department of Classics and Ancient History. (41). OCLC 179161486.

- ^ Norman-Culp, Sheila (23 November 1998). "British author rides up the charts on a wizard's tale". Associated Press Newswires.

Reprint Archived 14 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine at Accio Quote! (accio-quote.org). 24 February 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2007. - ^ Loer, Stephanie (18 October 1999). "All about Harry Potter from quidditch to the future of the Sorting Hat". The Boston Globe.

Reprint Archived 10 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine at Accio Quote! (accio-quote.org). No date. Retrieved 10 October 2007. - ^ "Harry Potter and Me". BBC Christmas Special. 2001. A&E Biography (American edition), 13 November 2002.

Reprint Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine (part 1 of 5) at Accio Quote! (accio-quote.org). Retrieved 25 February 2007. - ^ Transcript of Richard and Judy Archived 4 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Richard & Judy, Channel Four Corporation (UK). 26 June 2006. Retrieved 4 July 2006.

- ^ Weeks, Linton. "Charmed, I'm Sure" Archived 8 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post. 20 October 1999. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ^ Kirk, Connie Ann (2003). J.K. Rowling: A Biography. United States: Greenwood Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-313-32205-1. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

Soon, by many eyewitness accounts and even some versions of Jorge's own story, domestic violence became a painful reality in Jo's life.

- ^ "J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues". J.K. Rowling. 10 June 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

I've [...] never talked publicly about being a domestic abuse and sexual assault survivor. This isn't because I'm ashamed those things happened to me, but because they're traumatic to revisit and remember. I also feel protective of my daughter from my first marriage. I didn't want to claim sole ownership of a story that belongs to her, too. [...] I managed to escape my first violent marriage with some difficulty [...]

- ^ "JK Rowling: Sun newspaper criticised by abuse charities for article on ex-husband". BBC. 12 June 2020. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Grierson, Jamie (12 June 2020). "JK Rowling: UK domestic abuse adviser writes to Sun editor". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Rowling, JK (June 2008). "JK Rowling: The fringe benefits of failure". TED. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

Failure & imagination

- ^ "Harry Potter author: I considered suicide" Archived 25 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. CNN. 23 March 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ Harry Potter's magician Archived 12 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 18 February 2003. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- ^ "JK Rowling awarded honorary degree". The Daily Telegraph. London. 8 July 2004. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Anelli, Melissa (2008). Harry, A History: The True Story of a Boy Wizard, His Fans, and Life Inside the Harry Potter Phenomenon. New York: Pocket. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4165-5495-0. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- ^ a b Kirk, Connie Ann (2003). J.K. Rowling: A Biography. United States: Greenwood Press. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Dunn, Elisabeth (30 June 2007). "From the dole to Hollywood". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 April 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "JK Rowling – Biography on Bio". Biographies.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and Me" Archived 5 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. BBC Christmas Special. 28 December 2001. Transcribed by "Marvelous Marvolo" and Jimmi Thøgersen. Quick Quotes Quill.org. Retrieved 17 March 2006.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Desert Island Discs, J K Rowling". BBC.

- ^ Henderson, Damien (2007). "How JK Rowling has us spellbound". The Herald. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Riccio, Heather. Interview with JK Rowling, Author of Harry Potter Archived 31 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine . Hilary Magazine. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ^ "Meet the Writers: J. K. Rowling". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on 8 April 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Lawless, John (3 July 2005). "Revealed: The eight-year-old girl who saved Harry Potter". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Blais, Jacqueline (9 July 2005). Harry Potter has been very good to JK Rowling. USA Today. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ^ Scottish Arts Council Wants Payback Archived 18 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. hpna.com. 30 November 2003. Retrieved 9 April 2006.

- ^ Kleffel, Rick. Rare Harry Potter books Archived 17 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. metroactive.com. 22 July 2005. Retrieved 9 April 2006.

- ^ Reynolds, Nigel (7 July 1997). "$100,000 Success Story for Penniless Mother" Archived 26 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Red Nose Day" Online Chat Transcript, BBC, 12 March 2001, The Burrow. Retrieved 16 April 2008. Archived at Wayback Engine.

- ^ a b c "Harry Potter awards". Bloomsbury Publishing House. Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ Potter's award hat-trick Archived 26 May 2004 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 1 December 1999. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ Gibbons, Fiachra. "Beowulf slays the wizard" Archived 18 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. 26 January 2000. Retrieved 19 March 2006.

- ^ a b "Potter sales record" Archived 11 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters/PRNewswire. 11 July 2000. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ Johnstone, Anne. The hype surrounding the fourth Harry Potter book belies the fact that Joanne Rowling had some of her blackest moments writing it – and that the pressure was self-imposed; a kind of magic Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Herald. 8 July 2000. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ a b "JK Rowling Biography". Biography Channel. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

Rowling was named Author of The Year at the British Book Awards in 2000

- ^ Rowling denies writer's block Archived 13 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 8 August 2001. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ Grossman, Lev. "J.K. Rowling Hogwarts And All" Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Time magazine. 17 July 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ New Potter book topples U.S. sales records Archived 7 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine . NBC News. 18 July 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ Press Release. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine . Bloomsbury. 21 December 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ "Finish or bust – JK Rowling's unlikely message in an Edinburgh hotel room". The Scotsman. 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Rowling, J. K. "J.K.Rowling Official Site". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Harry Potter finale sales hit 11 m Archived 28 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 23 July 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ "Rowling to kill two in final book". BBC News. London. 27 June 2006. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.27 June 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ Pauli, Michelle. "June date for Harry Potter 5 Archived 28 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine". The Guardian (London); "Potter 'is fastest-selling book ever Archived 29 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ Sawyer, Jenny. Missing from 'Harry Potter' – a real moral struggle Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Christian Science Monitor. 25 July 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ Associated, By (29 June 2007). "Final Harry Potter is expected to set record". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. 29 June 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- ^ New Study Finds That the Harry Potter Series Has a Positive Impact on Kids' Reading and Their School Work Archived 24 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Scholastic. 25 July 2006. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ Mehegan, David (9 July 2007). "In end, Potter magic extends only so far". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ Walker, Andrew (9 October 1998). "Harry Potter is off to Hollywood – writer a Millionairess" Archived 27 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Scotsman. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ a b Harry Potter release dates Archived 9 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Half-Blood Prince Filming News: Threat of Strike to Affect Harry Potter Six?". The Leaky Cauldron. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016.19 September 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ Spelling, Ian. Yates Confirmed For Potter VI. Sci Fi Wire. 3 May 2007. "Scifi.com". Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- ^ Boucher, Jeff (13 March 2008). "Final 'Harry Potter' book will be split into two movies". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ "WB Sets Lots of New Release Dates!". Comingsoon.net. 24 February 2009. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ Treneman, Ann. J.K. Rowling, the interview Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Times. 30 June 2000. Retrieved 26 July 2006.