James Baldwin

James Baldwin | |

|---|---|

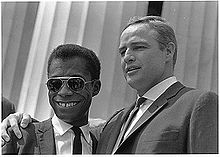

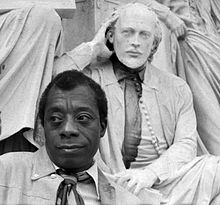

Baldwin in 1969 | |

| Born | August 2, 1924 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | December 1, 1987 (aged 63) Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France |

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery, Westchester County, New York |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, activist |

| Language | English |

| Education | DeWitt Clinton High School |

| Genre | |

| Notable works | |

| Years active | 1947–1985 |

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American novelist, playwright, essayist, poet, and activist. His essays, collected in Notes of a Native Son (1955), explore intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in the United States during the mid twentieth-century.[1] Some of Baldwin's essays are book-length, including The Fire Next Time (1963), No Name in the Street (1972), and The Devil Finds Work (1976). An unfinished manuscript, Remember This House, was expanded and adapted for cinema as the Academy Award–nominated documentary film I Am Not Your Negro (2016).[2][3] One of his novels, If Beale Street Could Talk, was adapted into the Academy Award-winning film of the same name in 2018, directed and produced by Barry Jenkins.

Baldwin's novels, short stories, and plays fictionalize fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures. Themes of masculinity, sexuality, race, and class intertwine to create intricate narratives that run parallel with some of the major political movements toward social change in mid-twentieth-century America, such as the civil rights movement and the gay liberation movement. Baldwin's protagonists are often but not exclusively African American, and gay and bisexual men frequently feature as protagonists in his literature. These characters often face internal and external obstacles in their search for social- and self-acceptance. Such dynamics are prominent in Baldwin's second novel, Giovanni's Room, which was written in 1956, well before the gay liberation movement.[4]

Early life[]

James Arthur Baldwin was born to Emma Berdis Jones[5] who had left Baldwin's biological father because of his drug abuse.[6] A native of an impoverished community on Deal Island, Maryland,[7] Jones moved to Harlem where Baldwin was born, in Harlem Hospital in New York. Jones married a Baptist preacher, David Baldwin with whom she had eight children between 1927 and 1943.[8] David Baldwin also had a son from a previous marriage who was nine years older than James.[8] The family was poor, and Baldwin's stepfather, to whom he referred in essays as his father, treated him more harshly than his biological children.[5] His intelligence, combined with the persecution he endured in his stepfather's home, drove Baldwin to spend much of his time alone in libraries.[9][10]

By the time Baldwin had reached adolescence, he had discovered his passion for writing. His educators deemed him gifted, and in 1937, at the age of 13, he wrote his first article, titled "Harlem—Then and Now", which was published in his school's magazine, The Douglass Pilot.[11]

Baldwin spent much time caring for his several younger brothers and sisters. At the age of 10, he was teased and abused by two New York police officers, an instance of the racist harassment by the NYPD that he would experience again as a teenager and document in his essays. His stepfather died of tuberculosis in the summer of 1943, on the day his last child was born, just before Baldwin turned 19. Not only would the day of the funeral be Baldwin's 19th birthday, it would also be that of the Harlem riot of 1943, an event portrayed at the beginning of his "Notes of a Native Son" essay.[12] During World War II, Baldwin worked laying track in a defense-related capacity.[13]

Education[]

Baldwin said, "I knew I was black, of course, but I also knew I was smart. I didn't know how I would use my mind, or even if I could, but that was the only thing I had to use." Baldwin attended P.S. 24 on 128th Street, between Fifth and Madison Avenues in Harlem where he wrote the school song, which was used until the school closed.[14]

As told in "Notes of a Native Son", when he was 10 years old, Baldwin wrote a play that was directed by a teacher at his school. Seeing his talent and potential, she offered to take him to "real" plays. This provoked a backlash from Baldwin's stepfather, as the teacher was white. Baldwin's mother eventually overruled his father, saying "it would not be very nice to let such a kind woman make the trip for nothing." When his teacher came to pick him up, Baldwin noticed that his stepfather was filled with disgust. Baldwin later realized that this encounter was an "unprecedented and frightening" situation for his parents:[15]

It was clear, during the brief interview in our living room, that my father was agreeing very much against his will and that he would have refused permission if he had dared. The fact that he did not dare caused me to despise him. I had no way of knowing that he was facing in that living room a wholly unprecedented and frightening situation.

His middle-school years were spent at Frederick Douglass Junior High, where he was influenced by poet Countee Cullen, a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance and was encouraged by his math teacher to serve as editor of the school newspaper, The Douglass Pilot.[16] (Directly preceding him as editors at Frederick Douglass Junior High were Brock Peters, the future actor and Bud Powell, the future jazz pianist.)[17]

He then went on to DeWitt Clinton High School in Bedford Park, in the Bronx.[18] There, along with Richard Avedon, Baldwin worked on the school magazine as literary editor but disliked school because of constant racial slurs.[19]

Religion[]

During his teenage years, Baldwin followed his stepfather's shadow into the religious life. The difficulties in his life including his stepfather's abuse led Baldwin to seek consolation in religion. At the age of 14, he attended meetings of the Pentecostal Church and, during a euphoric prayer meeting, he converted and became a junior minister. Before long, at the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly, he was drawing larger crowds than his stepfather had done in his day. At 17, however, Baldwin had come to view Christianity as based on false premises, considering it hypocritical and racist and later regarded his time in the pulpit as a way of overcoming his personal crises.[20] He left the church although his step-father wanted him to become a preacher.

Baldwin once visited Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, who inquired about Baldwin's religious beliefs. He answered, "I left the church 20 years ago and haven't joined anything since." Elijah asked, "And what are you now?" Baldwin explained, "Now? Nothing. I'm a writer. I like doing things alone."[21] Still, his church experience significantly shaped his worldview and writing.[22] In his essay The Fire Next Time, Baldwin reflected that "being in the pulpit was like working in the theatre; I was behind the scenes and knew how the illusion was worked."[23]

Baldwin accused Christianity of reinforcing the system of American slavery by palliating the pangs of oppression and delaying salvation until a promised afterlife.[24] Baldwin praised religion, however, for inspiring some Black Americans to defy oppression.[24] He once wrote, "If the concept of God has any use, it is to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God can't do that, it's time we got rid of him."[25] Baldwin publicly described himself as non-religious.[26]

Greenwich Village[]

When Baldwin was 15 years old, his high-school running buddy, Emile Capouya, skipped school one day and met Beauford Delaney, a modernist painter, in Greenwich Village.[27] Capouya gave Baldwin Delaney's address and suggested that he pay him a visit.[27] Baldwin, who at the time worked after school in a sweatshop on nearby Canal Street, visited Delaney at 181 Greene Street. Delaney became a mentor to Baldwin, and, under his influence, Baldwin came to believe a black person could be an artist.[27]

Baldwin moved to Greenwich village in 1943.[28] While working odd jobs, Baldwin wrote short stories, essays, and book reviews, some of them later collected in the volume Notes of a Native Son (1955). He befriended actor Marlon Brando in 1944, and the two were roommates for a time.[29] They remained friends for over twenty years.

Emigration[]

In 1948 New Jersey, Baldwin walked into a restaurant that only served white people. When the waitress refused to serve him, Baldwin threw a glass of water at her which shattered against the mirror behind the bar.[30]

Disillusioned by American prejudice against black people, as well as wanting to see himself and his writing outside of an African-American context, he left the United States at the age of 24 to settle in Paris. Baldwin wanted not to be read as "merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer."[31] He also hoped to come to terms with his sexual ambivalence and escape the hopelessness that many young African-American men like himself succumbed to in New York.[32]

In Paris, Baldwin was soon involved in the cultural radicalism of the Left Bank. He started to publish his work in literary anthologies, notably Zero[33] which was edited by his friend Themistocles Hoetis and which had already published essays by Richard Wright.

Baldwin lived in France for most of his later life. He also spent some time in Switzerland and Turkey.[34][35] During his lifetime, as well as since his death, Baldwin was seen not only as an influential African-American writer but also as an influential emigrant writer, particularly because of his numerous experiences outside the United States and the impact of these experiences on his life and his writing.

Saint-Paul-de-Vence[]

Baldwin settled in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the south of France in 1970, in an old Provençal house beneath the ramparts of the famous village.[36] His house was always open to his friends who frequently visited him while on trips to the French Riviera. American painter Beauford Delaney made Baldwin's house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence his second home, often setting up his easel in the garden. Delaney painted several colorful portraits of Baldwin. Fred Nall Hollis also befriended Baldwin during this time. Actors Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier were also regular house guests.

Many of Baldwin's musician friends dropped in during the Jazz à Juan and Nice Jazz Festivals. They included Nina Simone, Josephine Baker (whose sister lived in Nice), Miles Davis, and Ray Charles.[37] In his autobiography, Miles Davis wrote:[38]

I'd read his books and I liked and respected what he had to say. As I got to know Jimmy we opened up to each other and became real great friends. Every time I went to southern France to play Antibes, I would always spend a day or two out at Jimmy's house in St. Paul de Vence. We'd just sit there in that great big beautiful house of his telling us all kinds of stories, lying our asses off.... He was a great man.

Baldwin learned to speak French fluently and developed friendships with French actor Yves Montand and French writer Marguerite Yourcenar who translated Baldwin's play The Amen Corner into French.

The years Baldwin spent in Saint-Paul-de-Vence were also years of work. Sitting in front of his sturdy typewriter, he devoted his days to writing and to answering the huge amount of mail he received from all over the world. He wrote several of his last works in his house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, including Just Above My Head in 1979 and Evidence of Things Not Seen in 1985. It was also in his Saint-Paul-de-Vence house that Baldwin wrote his famous "Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis" in November 1970.[39][40]

Following Baldwin's death in 1987, a court battle began over the ownership of his home. Baldwin had been in the process of purchasing his house from his landlady, Mlle. Jeanne Faure.[41] At the time of his death, Baldwin did not have full ownership of the home, although it was still Mlle. Faure's intention that the home would stay in the family. His home, nicknamed "Chez Baldwin",[42] has been the center of scholarly work and artistic and political activism. The National Museum of African American History and Culture has an online exhibit titled "Chez Baldwin" which uses his historic French home as a lens to explore his life and legacy.[43] Magdalena J. Zaborowska's 2018 book, Me and My House: James Baldwin's Last Decade in France, uses photographs of his home and his collections to discuss themes of politics, race, queerness, and domesticity.[44]

Over the years, several efforts were initiated to save the house and convert it into an artist residency. None had the endorsement of the Baldwin estate. In February 2016, Le Monde published an opinion piece by Thomas Chatterton Williams, a contemporary Black American expatriate writer in France, which spurred a group of activists to come together in Paris.[45] In June 2016, American writer and activist Shannon Cain squatted at the house for 10 days in an act of political and artistic protest.[46][47] Les Amis de la Maison Baldwin, a French organization whose initial goal was to purchase the house by launching a capital campaign funded by the U.S. philanthropic sector, grew out of this effort.[48] This campaign was unsuccessful without the support of the Baldwin Estate. Attempts to engage the French government in conservation of the property were dismissed by the mayor of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Joseph Le Chapelain whose statement to the local press claiming "nobody's ever heard of James Baldwin" mirrored those of Henri Chambon, the owner of the corporation that razed his home.[49][50] Construction was completed in 2019 on the apartment complex that now stands where Chez Baldwin once stood.

Literary career[]

Baldwin's first published work, a review of the writer Maxim Gorky, appeared in The Nation in 1947.[51][52] He continued to publish in that magazine at various times in his career and was serving on its editorial board at his death in 1987.[52]

1950s[]

In 1953, Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical bildungsroman was published. He began writing it when he was only seventeen and first published it in Paris. His first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son appeared two years later. He continued to experiment with literary forms throughout his career, publishing poetry and plays as well as the fiction and essays for which he was known.

Baldwin's second novel, Giovanni's Room, caused great controversy when it was first published in 1956 due to its explicit homoerotic content.[53] Baldwin again resisted labels with the publication of this work.[54] Despite the reading public's expectations that he would publish works dealing with African American experiences, Giovanni's Room is predominantly about white characters.[54]

1960s[]

Baldwin's third and fourth novels, Another Country (1962) and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968), are sprawling, experimental works[55] dealing with black and white characters, as well as with heterosexual, gay, and bisexual characters.[56]

Baldwin's lengthy essay "Down at the Cross" (frequently called The Fire Next Time after the title of the 1963 book in which it was published)[57] similarly showed the seething discontent of the 1960s in novel form. The essay was originally published in two oversized issues of The New Yorker and landed Baldwin on the cover of Time magazine in 1963 while he was touring the South speaking about the restive Civil Rights Movement. Around the time of publication of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin became a known spokesperson for civil rights and a celebrity noted for championing the cause of Black Americans. He frequently appeared on television and delivered speeches on college campuses.[58] The essay talked about the uneasy relationship between Christianity and the burgeoning Black Muslim movement. After publication, several Black nationalists criticized Baldwin for his conciliatory attitude. They questioned whether his message of love and understanding would do much to change race relations in America.[58] The book was consumed by whites looking for answers to the question: What do Black Americans really want? Baldwin's essays never stopped articulating the anger and frustration felt by real-life Black Americans with more clarity and style than any other writer of his generation.[59]

1970s and 1980s[]

Baldwin's next book-length essay, No Name in the Street (1972), also discussed his own experience in the context of the later 1960s, specifically the assassinations of three of his personal friends: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Baldwin's writings of the 1970s and 1980s were largely overlooked by critics, although they have received increasing attention in recent years.[60] Several of his essays and interviews of the 1980s discuss homosexuality and homophobia with fervor and forthrightness.[58] Eldridge Cleaver's harsh criticism of Baldwin in Soul on Ice and elsewhere[61] and Baldwin's return to southern France contributed to the perception by critics that he was not in touch with his readership.[62][63][64] As he had been the leading literary voice of the civil rights movement, he became an inspirational figure for the emerging gay rights movement.[58] His two novels written in the 1970s, If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) and Just Above My Head (1979), placed a strong emphasis on the importance of Black American families. He concluded his career by publishing a volume of poetry, Jimmy's Blues (1983), as well as another book-length essay, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), an extended reflection on race inspired by the Atlanta murders of 1979–1981.

Social and political activism[]

Baldwin returned to the United States in the summer of 1957 while the civil rights legislation of that year was being debated in Congress. He had been powerfully moved by the image of a young girl, Dorothy Counts, braving a mob in an attempt to desegregate schools in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Partisan Review editor Philip Rahv had suggested he report on what was happening in the American South. Baldwin was nervous about the trip but he made it, interviewing people in Charlotte (where he met Martin Luther King Jr.), and Montgomery, Alabama. The result was two essays, one published in Harper's magazine ("The Hard Kind of Courage"), the other in Partisan Review ("Nobody Knows My Name"). Subsequent Baldwin articles on the movement appeared in Mademoiselle, Harper's, The New York Times Magazine, and The New Yorker, where in 1962 he published the essay that he called "Down at the Cross", and the New Yorker called "Letter from a Region of My Mind". Along with a shorter essay from The Progressive, the essay became The Fire Next Time.[65]: 94–99, 155–56

| External audio | |

|---|---|

While he wrote about the movement, Baldwin aligned himself with the ideals of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Joining CORE gave him the opportunity to travel across the American South lecturing on his views of racial inequality. His insights into both the North and South gave him a unique perspective on the racial problems the United States was facing.

In 1963 he conducted a lecture tour of the South for CORE, traveling to Durham and Greensboro in North Carolina, and New Orleans. During the tour, he lectured to students, white liberals, and anyone else listening about his racial ideology, an ideological position between the "muscular approach" of Malcolm X and the nonviolent program of Martin Luther King, Jr.[67] Baldwin expressed the hope that socialism would take root in the United States.[68]

"It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have." - James Baldwin

By the spring of 1963, the mainstream press began to recognize Baldwin's incisive analysis of white racism and his eloquent descriptions of the Negro's pain and frustration. In fact, Time featured Baldwin on the cover of its May 17, 1963, issue. "There is not another writer", said Time, "who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South."[69][65]: 175

In a cable Baldwin sent to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy during the Birmingham, Alabama crisis, Baldwin blamed the violence in Birmingham on the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, Mississippi Senator James Eastland, and President Kennedy for failing to use "the great prestige of his office as the moral forum which it can be." Attorney General Kennedy invited Baldwin to meet with him over breakfast, and that meeting was followed up with a second, when Kennedy met with Baldwin and others Baldwin had invited to Kennedy's Manhattan apartment. This meeting is discussed in Howard Simon's 1999 play, James Baldwin: A Soul on Fire. The delegation included Kenneth B. Clark, a psychologist who had played a key role in the Brown v. Board of Education decision; actor Harry Belafonte, singer Lena Horne, writer Lorraine Hansberry, and activists from civil rights organizations.[65]: 176–80 Although most of the attendees of this meeting left feeling "devastated", the meeting was an important one in voicing the concerns of the civil rights movement, and it provided exposure of the civil rights issue not just as a political issue but also as a moral issue.[70]

James Baldwin's FBI file contains 1,884 pages of documents, collected from 1960 until the early 1970s.[71] During that era of surveillance of American writers, the FBI accumulated 276 pages on Richard Wright, 110 pages on Truman Capote, and just nine pages on Henry Miller.

Baldwin also made a prominent appearance at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, with Belafonte and long-time friends Sidney Poitier and Marlon Brando.[72]

Baldwin's sexuality clashed with his activism. The civil rights movement was hostile to homosexuals.[73][74] The only out gay men in the movement were James Baldwin and Bayard Rustin. Rustin and King were very close, as Rustin received credit for the success of the March on Washington. Many were bothered by Rustin's sexual orientation. King himself spoke on the topic of sexual orientation in a school editorial column during his college years, and in reply to a letter during the 1950s, where he treated it as a mental illness which an individual could overcome. King's key advisor, Stanley Levison, also stated that Baldwin and Rustin were "better qualified to lead a homo-sexual movement than a civil rights movement"[75] The pressure later resulted in King distancing himself from both men. Despite his enormous efforts within the movement, due to his sexuality, Baldwin was excluded from the inner circles of the civil rights movement and was conspicuously uninvited to speak at the end of the March on Washington.[76]

At the time, Baldwin was neither in the closet nor open to the public about his sexual orientation. Although his novels, specifically Giovanni's Room and Just Above My Head, had openly gay characters and relationships, Baldwin himself never openly stated his sexuality. In his book, Kevin Mumford points out how Baldwin went his life "passing as straight rather than confronting homophobes with whom he mobilised against racism".[77]

After a bomb exploded in a Birmingham church three weeks after the March on Washington, Baldwin called for a nationwide campaign of civil disobedience in response to this "terrifying crisis". He traveled to Selma, Alabama, where SNCC had organized a voter registration drive; he watched mothers with babies and elderly men and women standing in long lines for hours, as armed deputies and state troopers stood by—or intervened to smash a reporter's camera or use cattle prods on SNCC workers. After his day of watching, he spoke in a crowded church, blaming Washington—"the good white people on the hill". Returning to Washington, he told a New York Post reporter the federal government could protect Negroes—it could send federal troops into the South. He blamed the Kennedys for not acting.[65]: 191, 195–98 In March 1965, Baldwin joined marchers who walked 50 miles from Selma, Alabama, to the capitol in Montgomery under the protection of federal troops.[65]: 236

Nonetheless, he rejected the label "civil rights activist", or that he had participated in a civil rights movement, instead agreeing with Malcolm X's assertion that if one is a citizen, one should not have to fight for one's civil rights. In a 1964 interview with Robert Penn Warren for the book Who Speaks for the Negro?, Baldwin rejected the idea that the civil rights movement was an outright revolution, instead calling it "a very peculiar revolution because it has to... have its aims the establishment of a union, and a... radical shift in the American mores, the American way of life... not only as it applies to the Negro obviously, but as it applies to every citizen of the country."[78] In a 1979 speech at UC Berkeley, he called it, instead, "the latest slave rebellion".[79]

In 1968, Baldwin signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[80]

Inspiration and relationships[]

As a young man, Baldwin's poetry teacher was Countee Cullen.[81]

A great influence on Baldwin was the painter Beauford Delaney. In The Price of the Ticket (1985), Baldwin describes Delaney as

... the first living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognized as my teacher and I as his pupil. He became, for me, an example of courage and integrity, humility and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow.

Later support came from Richard Wright, whom Baldwin called "the greatest black writer in the world". Wright and Baldwin became friends, and Wright helped Baldwin secure the Eugene F. Saxon Memorial Award. Baldwin's essay "Notes of a Native Son" and his collection Notes of a Native Son allude to Wright's novel Native Son. In Baldwin's 1949 essay "Everybody's Protest Novel", however, he indicated that Native Son, like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, lacked credible characters and psychological complexity, and the friendship between the two authors ended.[82] Interviewed by Julius Lester,[83] however, Baldwin explained "I knew Richard and I loved him. I was not attacking him; I was trying to clarify something for myself." In 1965, Baldwin participated in a debate with William F. Buckley, on the topic of whether the American dream had been achieved at the expense of African Americans. The debate took place at The Cambridge Union in the UK. The spectating student body voted overwhelmingly in Baldwin's favor.[84][85]

In 1949 Baldwin met and fell in love with Lucien Happersberger, a boy aged 17, though Happersberger's marriage three years later left Baldwin distraught. When the marriage ended they later reconciled, with Happersberger staying by Baldwin's deathbed at their house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence.[86] Happersberger died on August 21, 2010, in Switzerland.[87]

Baldwin was a close friend of the singer, pianist, and civil rights activist Nina Simone. Langston Hughes, Lorraine Hansberry, and Baldwin helped Simone learn about the Civil Rights Movement. Baldwin also provided her with literary references influential on her later work. Baldwin and Hansberry met with Robert F. Kennedy, along with Kenneth Clark and Lena Horne and others in an attempt to persuade Kennedy of the importance of civil rights legislation.[88]

Baldwin influenced the work of French painter Philippe Derome, whom he met in Paris in the early 1960s. Baldwin also knew Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Billy Dee Williams, Huey P. Newton, Nikki Giovanni, Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Genet (with whom he campaigned on behalf of the Black Panther Party), Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan, Rip Torn, Alex Haley, Miles Davis, Amiri Baraka, Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, Margaret Mead, Josephine Baker, Allen Ginsberg, Chinua Achebe, and Maya Angelou. He wrote at length about his "political relationship" with Malcolm X. He collaborated with childhood friend Richard Avedon on the 1964 book Nothing Personal.[89]

Maya Angelou called Baldwin her "friend and brother" and credited him for "setting the stage" for her 1969 autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Baldwin was made a Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur by the French government in 1986.[90]

Baldwin was also a close friend of Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison. Upon his death, Morrison wrote a eulogy for Baldwin that appeared in The New York Times. In the eulogy, entitled "Life in His Language", Morrison credits Baldwin as being her literary inspiration and the person who showed her the true potential of writing. She writes:

You knew, didn't you, how I needed your language and the mind that formed it? How I relied on your fierce courage to tame wildernesses for me? How strengthened I was by the certainty that came from knowing you would never hurt me? You knew, didn't you, how I loved your love? You knew. This then is no calamity. No. This is jubilee. 'Our crown,' you said, 'has already been bought and paid for. All we have to do,' you said, 'is wear it.'[91]

Death[]

On December 1, 1987,[92][93][94][95] Baldwin died from stomach cancer in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France.[96][97][98] He was buried at the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, near New York City.[99]

Fred Nall Hollis took care of James Baldwin on his deathbed. Nall had been friends with Baldwin from the early 1970s because Baldwin would buy him drinks at the Café de Flore. Nall recalled talking to Baldwin shortly before his death about racism in Alabama. In one conversation, Nall told Baldwin "Through your books you liberated me from my guilt about being so bigoted coming from Alabama and because of my homosexuality." Baldwin insisted: "No, you liberated me in revealing this to me."[100]

At the time of Baldwin's death, he was working on an unfinished manuscript called Remember This House, a memoir of his personal recollections of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.[101] Following his death, publishing company McGraw-Hill took the unprecedented step of suing his estate to recover the $200,000 advance they had paid him for the book, although the lawsuit was dropped by 1990.[101] The manuscript forms the basis for Raoul Peck's 2016 documentary film I Am Not Your Negro.[102]

Legacy and critical response[]

Literary critic Harold Bloom characterized Baldwin as "among the most considerable moral essayists in the United States".[103]

Baldwin's influence on other writers has been profound: Toni Morrison edited the Library of America's first two volumes of Baldwin's fiction and essays: Early Novels & Stories (1998) and Collected Essays (1998). A third volume, Later Novels (2015), was edited by Darryl Pinckney, who had delivered a talk on Baldwin in February 2013 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of The New York Review of Books, during which he stated: "No other black writer I'd read was as literary as Baldwin in his early essays, not even Ralph Ellison. There is something wild in the beauty of Baldwin's sentences and the cool of his tone, something improbable, too, this meeting of Henry James, the Bible, and Harlem."[104]

One of Baldwin's richest short stories, "Sonny's Blues", appears in many anthologies of short fiction used in introductory college literature classes.

A street in San Francisco, Baldwin Court in the Bayview neighborhood is named after Baldwin.[105]

In the 1986 work The Story of English, Robert MacNeil, with Robert McCrum and William Cran, mentioned James Baldwin as an influential writer of African American Literature, on the level of Booker T. Washington, and held both men up as prime examples of Black writers.

In 1987, Kevin Brown, a photo-journalist from Baltimore founded the National James Baldwin Literary Society. The group organizes free public events celebrating Baldwin's life and legacy.

In 1992, Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, established the James Baldwin Scholars program, an urban outreach initiative, in honor of Baldwin, who taught at Hampshire in the early 1980s. The JBS Program provides talented students of color from under-served communities an opportunity to develop and improve the skills necessary for college success through coursework and tutorial support for one transitional year, after which Baldwin scholars may apply for full matriculation to Hampshire or any other four-year college program.

Spike Lee's 1996 film Get on the Bus includes a black gay character, played by Isaiah Washington, who punches a homophobic character, saying: "This is for James Baldwin and Langston Hughes."

His name appears in the lyrics of the Le Tigre song "Hot Topic", released in 1999.[106]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included James Baldwin on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[107]

In 2005, the United States Postal Service created a first-class postage stamp dedicated to Baldwin, which featured him on the front with a short biography on the back of the peeling paper.

In 2012, Baldwin was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display that celebrates LGBT history and people.[108]

In 2014, East 128th Street, between Fifth and Madison Avenues was named "James Baldwin Place" to celebrate the 90th anniversary of Baldwin's birth. He lived in the neighborhood and attended P.S. 24. Readings of Baldwin's writing were held at The National Black Theatre and a month long art exhibition featuring works by New York Live Arts and artist Maureen Kelleher. The events were attended by Council Member Inez Dickens, who led the campaign to honor Harlem native's son; also taking part were Baldwin's family, theatre and film notables, and members of the community.[109][110]

Also in 2014, Baldwin was one of the inaugural honorees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighborhood celebrating LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields."[111][112][113]

Also in 2014, The Social Justice Hub at The New School's newly opened University Center was named the Baldwin Rivera Boggs Center after activists Baldwin, Sylvia Rivera, and Grace Lee Boggs.[114]

In 2016, Raoul Peck released his documentary film I Am Not Your Negro. It is based on James Baldwin's unfinished manuscript, Remember This House. It is a 93-minute journey into black history that connects the past of the Civil Rights Movement to the present of Black Lives Matter. It is a film that questions black representation in Hollywood and beyond.

In 2017, Scott Timberg wrote an essay for the Los Angeles Times ("30 years after his death, James Baldwin is having a new pop culture moment") in which he noted existing cultural references to Baldwin, 30 years after his death, and concluded: "So Baldwin is not just a writer for the ages, but a scribe whose work—as squarely as George Orwell's—speaks directly to ours."[115]

In June 2019 Baldwin's residence on the Upper West Side was given landmark designation by New York City's Landmarks Preservation Commission.[116][117]

In June 2019, Baldwin was one of the inaugural fifty American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City's Stonewall Inn.[118][119] The SNM is the first U.S. national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history,[120] and the wall's unveiling was timed to take place during the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.[121]

At the Paris Council of June 2019, the city of Paris voted unanimously by all political groups to name a place in the capital in the name of James Baldwin. The project was confirmed on June 19, 2019, and announced for the year 2020. In 2021, Paris City Hall announced that the writer would give his name to the very first media library in the 19th arrondissement, which is scheduled to open in 2023.[122]

Honors and awards[]

- Guggenheim Fellowship, 1954.

- Eugene F. Saxton Memorial Trust Award

- Foreign Drama Critics Award

- George Polk Memorial Award, 1963

- MacDowell fellowships: 1954, 1958, 1960[123]

- Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur, 1986

Works[]

Novels[]

- 1953. Go Tell It on the Mountain (semi-autobiographical)

- 1956. Giovanni's Room

- 1962. Another Country

- 1968. Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone

- 1974. If Beale Street Could Talk

- 1979. Just Above My Head

Essays and short stories[]

Many essays and short stories by Baldwin were published for the first time as part of collections (e.g. Notes of a Native Son). Others, however, were published individually at first and later included with Baldwin's compilation books. Some essays and stories of Baldwin's that were originally released on their own include:

- 1953. "Stranger in the Village". Harper's Magazine.[124][125]

- 1954. "Gide as Husband and Homosexual". The New Leader.

- 1956. "Faulkner and Desegregation". Partisan Review.

- 1957. "Sonny's Blues". Partisan Review.

- 1957. "Princes and Powers". Encounter.

- 1958. "The Hard Kind of Courage". Harper's Magazine.

- 1959. "The Discovery of What It Means to Be an American". The New York Times Book Review.

- 1959. "Nobody Knows My Name: A Letter from the South". Partisan Review.

- 1960. "Fifth Avenue, Uptown: A Letter from Harlem". Esquire.

- 1960. "The Precarious Vogue of Ingmar Bergman". Esquire.

- 1961. "A Negro Assays the Negro Mood". New York Times Magazine.

- 1961. "The Survival of Richard Wright". Reporter.

- 1961. "Richard Wright". Encounter.[126]

- 1962. "Letter from a Region of My Mind". The New Yorker.[127]

- 1962. "My Dungeon Shook". The Progressive.[128]

- 1963. "A Talk to Teachers"[129]

- 1967. "Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They're Anti-White". New York Times Magazine.[130]

- 1976. The Devil Finds Work — a book-length essay published by Dial Press.

Collections[]

Many essays and short stories by Baldwin were published for the first time as part of collections, which also included older, individually-published works (such as above) of Baldwin's as well. These collections include:

- 1955. Notes of a Native Son[131]

- 1961. Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son

- 1963. The Fire Next Time

- 1965. Going to Meet the Man

- 1972. No Name in the Street

- 1983. Jimmy's Blues

- 1985. The Evidence of Things Not Seen

- 1985. The Price of the Ticket

- 2010. The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings.[132]

Plays and audio[]

- 1954 The Amen Corner (play)

- 1964. Blues for Mister Charlie (play)

- 1990. A Lover's Question (album). Les Disques Du Crépuscule – TWI 928–2.

Collaborative works[]

- 1964. Nothing Personal, with Richard Avedon (photography)

- 1971. A Rap on Race, with Margaret Mead

- 1971. A Passenger from the West, narrative with Baldwin conversations, by Nabile Farès; appended with long-lost interview.

- 1972. One Day When I Was Lost (orig.: A. Haley)

- 1973. A Dialogue, with Nikki Giovanni

- 1976. Little Man Little Man: A Story of Childhood, with Yoran Cazac

- 2004. Native Sons, with Sol Stein

Posthumous collections[]

- 1998. Early Novels & Stories: Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni's Room, Another Country, Going to Meet the Man, edited by Toni Morrison.[133]

- 1998. Collected Essays: Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, The Devil Finds Work, Other Essays, edited by Toni Morrison.[134]

- 2014. Jimmy's Blues and Other Poems.[135]

- 2015. Later Novels: Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, If Beale Street Could Talk, Just Above My Head, edited by Darryl Pinckney.[136]

- 2016. Baldwin for Our Times: Writings from James Baldwin for an Age of Sorrow and Struggle, with notes and introduction by Rich Blint.[137]

Media appearances[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

- 1963-06-24. "A Conversation With James Baldwin", is a television interview recorded by WGBH following the Baldwin–Kennedy meeting.[138]

- 1963-02-04. Take This Hammer is a television documentary made with Richard O. Moore on KQED about Blacks in San Francisco in the late 1950s.[139]

- 1965-06-14. "Debate: Baldwin vs. Buckley", recorded by the BBC is a one-hour television special program featuring a debate between Baldwin and leading American conservative William F. Buckley, Jr., at the Cambridge Union, Cambridge University, England.[140]

- 1971. Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris. Documentary. Directed by Terence Dixon. .[141]

- 1974. James Baldwin talks about race, political struggle and the human condition at the Wheeler Hall, Berkeley, CA.[142]

- 1975. "Assignment America; 119; Conversation with a Native Son", from WNET features a television conversation between Baldwin and Maya Angelou.[143]

- 1976. "Pantechnicon; James Baldwin", is a radio program recorded by WGBH. Baldwin discusses his new book called "The Devil Finds Work" which is also representative of the way Baldwin takes a look at the American films and myth.[144]

See also[]

- LGBT culture in New York City

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of American novelists

- List of LGBT writers

- List of LGBT people from New York City

References[]

- ^ "About the Author." Take This Hammer (American Masters). US: Channel Thirteen-PBS. November 29, 2006. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Peck, Raoul, Rémi Grellety, and Hébert Peck, nominees. "I Am Not Your Negro | 2016 Documentary (Feature) Nominee". The Oscars. 2017. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017.

- ^ I Am Not Your Negro (2016) at IMDb.

- ^ Gounardoo, Jean-François; Rodgers, Joseph J. (1992). The Racial Problem in the Works of Richard Wright and James Baldwin. Greenwood Press. pp. 158, 148–200.

- ^ a b Smith, Jessie Carney. 1998. "James Baldwin." In Notable Black American Men II. Detroit: Gale. Retrieved January 14, 2018 via Biography in Context (database).

- ^ Bardi, Jennifer. [2017] 2018. "'Humanist Profile': James Baldwin." The Humanist 77(2):1. ISSN 0018-7399.

- ^ Brockell, Gillian (May 9, 2021). "The mothers of Malcolm X, MLK and James Baldwin: New book explores how they shaped their sons". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "James Baldwin Biography." Biography.com. US: A&E Television Networks. [2014] 2020.

- ^ Als, Hilton (February 9, 1998). "The Making and Unmaking of James Baldwin". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Jackson, Miles M., Jr. (January 1967). "Viewpoint: Books and Poverty Do Mix". Negro Digest: 41.

- ^ Sullivan, Charles (1991). Children of Promise: African-American literature and art for young people. New York: Harry N. Abram. ISBN 978-0810931701. OCLC 23143247.

- ^ Baldwin, James (1985). "Notes of a Native Son". The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985. Macmillan. ISBN 9780312643065.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia B. (December 14, 2018). "How If Beale Street Could Talk Author James Baldwin Went From Literary Critic to Civil-Rights Icon". Time. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ DKDMedia. July 30, 2014. David Baldwin Remembers P.S. 24 School on Vimeo.

- ^ Notes of a Native Son. Boston : Beacon Press. 2012. ISBN 978-080700611-5.

- ^ "James Baldwin | Artist Bios." Goodman Theatre. Chicago. 2020.

- ^ Pullman, Peter (2012). Wail: The Life of Bud Powell. Brooklyn, NY: Bop Changes. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-9851418-1-3.

- ^ Allyn, Bobby. July 21, 2009. "DeWitt Clinton's remarkable alumni", City Room (blog). The New York Times.

- ^ "Richard Avedon." The Daily Telegraph. October 2, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2009: "He also edited the school magazine at DeWitt Clinton High, on which the black American writer James Baldwin was literary editor."

- ^ Baldwin, James (November 17, 1962). "Letter from a Region in My Mind". New Yorker. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Baldwin, James (1963). The Fire Next Time. Down at the Cross—Letter from a Region of My Mind: Vintage. ISBN 9780312643065.

- ^ James, Chireau Y. (2005). "Baldwin's God: Sex, Hope and Crisis in Black Holiness Culture". Church History. 74 (4): 883–884. doi:10.1017/s0009640700101210. S2CID 167133069.

- ^ Baldwin, James. [1963] 1993. The Fire Next Time. New York: Vintage Books. p. 37.

- ^ a b "James Baldwin wrote about race and identity in America". Learning English. Voice of America. September 30, 2006.

- ^ Winston, Kimberly. February 23, 2012. "Blacks say atheists were unseen civil rights heroes." USA Today.

- ^ "Malcolm X Debate With James Baldwin September 5, 1963" (audio). via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Baldwin, James. 1985. The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985. New York: St Martin's Press. p. ix.

- ^ "James Baldwin Residence – NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project". www.nyclgbtsites.org. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Field, Douglas (2009). A Historical Guide to James Baldwin. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0195366532.

- ^ Thorsen, Karen, dir. 1989. James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket (American Masters), edited by S. Olswang. US: Channel Thirteen-PBS.

- ^ Baldwin, James. 1985. "The Discovery of What it Means to be an American." Ch. 18 in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 171.

- ^ Baldwin, James, "Fifth Avenue, Uptown" in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985 (New York: St. Martin's/Marek, 1985), 206.

- ^ Zero: A Review of Literature and Art. New York: Arno Press. 1974. ISBN 978-0-405-01753-7.

- ^ "James Baldwin." MSN Encarta. Microsoft. 2009. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009.

- ^ Zaborowska, Magdalena (2008). James Baldwin's Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4144-4.

- ^ "Freelance | TLS". March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Roullier, Alain. 1998. Le Gardien des âmes [The Guardian of Souls]. p. 534. [1]

- ^ Davis, Miles. 1989. Miles, the Autobiography, edited by Q.Troupe. Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Baldwin, James. November 19, 1970. "An Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis." via History is a Weapon.

- ^ Baldwin, James (January 7, 1971). "An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis". New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Postlethwaite, Justin (December 19, 2017). "Exploring Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Where James Baldwin Took Refuge in Provence". France Today. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Thomas Chatterton (October 28, 2015). "Breaking Into James Baldwin's House". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Chez Baldwin". National Museum of African American History and Culture. July 29, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ Zaborowska, Magdalena J. (2018). ""You have to get where you are before you can see where you've been": Searching for Black Queer Domesticity at Chez Baldwin". James Baldwin Review. 4: 72–91. doi:10.7227/JBR.4.6 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "France must save James Baldwin's house". Le Monde.fr (in French). March 11, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Une militante squatte la maison Baldwin à Saint-Paul pour empêcher sa démolition". Nice-Matin (in French). June 30, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "I Squatted James Baldwin's House in Order to Save It". Literary Hub. July 14, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Saint-Paul : 10 millions pour réhabiliter la maison Baldwin". Nice-Matin (in French). October 22, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Gros travaux sur l'ex-maison de l'écrivain James Baldwin à Saint-Paul-de-Vence". Nice-Matin (in French). November 20, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "La mairie a bloqué le chantier de l'ex-maison Baldwin: les concepteurs des "Jardins des Arts" s'expliquent". Nice-Matin (in French). September 6, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ Baldwin, James (April 12, 1947). "Maxim Gorki as Artist". The Nation. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b vanden Heuvel, Katrina, ed. (1990). The Nation: 1865-1990. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-1560250012.

- ^ Field, Douglas (2005). "Passing as a Cold War novel: anxiety and assimilation in James Baldwin's Giovanni's Room". In Field, Douglas (ed.). American Cold War Culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 88–106.

- ^ a b Balfour, Lawrie (2001). The Evidence of Things Not Said: James Baldwin and the Promise of American Democracy. Cornell University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8014-8698-2.

- ^ Miller, D. Quentin (2003). "James Baldwin". In Parini, Jay (ed.). American Writers Retrospective Supplement II. Scribner's. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-0684312491.

- ^ Goodman, Paul (June 24, 1962). "Not Enough of a World to Grow In (review of Another Country)". The New York Times.

- ^ Binn, Sheldon (January 31, 1963). "Review of The Fire Next Time". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Palmer, Colin A. "Baldwin, James", Encyclopedia of African American Culture and History, 2nd edn, 2005. Print.

- ^ Page, Clarence (December 16, 1987). "James Baldwin: Bearing Witness To The Truth". Chicago News Tribune.

- ^ Altman, Elias (May 2, 2011). "Watered Whiskey: James Baldwin's Uncollected Writings". The Nation.

- ^ Cleaver, Eldridge, "Notes On a Native Son", Ramparts, June 1966, pp. 51–57.

- ^ Vogel, Joseph (2018). James Baldwin and the 1980s: Witnessing the Reagan Era. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252041747.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Miller, Quentin D. (ed.) (2019). James Baldwin in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–89. ISBN 9781108636025.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) - ^ Field, Douglas (ed.) (2009). A Historical Guide to James Baldwin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0195366549.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Polsgrove, Carol (2001). Divided minds : intellectuals and the civil rights movement (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393020137.

- ^ "National Press Club Luncheon Speakers, James Baldwin, December 10, 1986". National Press Club via Library of Congress. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Leeming, David, James Baldwin: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt, 1994), 134.

- ^ Standley, Fred L., and Louis H. Pratt (eds), Conversations with James Baldwin, p. 131. September 1972, Walker: "Most newly independent countries in the world are moving in a socialist direction. Do you think socialism will ever come to the U.S.A.? Baldwin: I would think so. I don't see any other way for it to go. But then you have to be very careful what you mean by socialism. When I use the word I'm not thinking about Lenin for example ... Bobby Seale talks about a Yankee Doodle-type socialism ... So that a socialism achieved in America, if and when we do ... will be a socialism very unlike the Chinese socialism or the Cuban socialism. Walker: What unique form do you envision socialism in the U.S.A. taking? Baldwin: I don't know, but the price of any real socialism here is the eradication of what we call the race problem ... Racism is crucial to the system to keep Black[s] and whites at a division so both were and are a source of cheap labor."

- ^ "The Negro's Push for Equality (cover title); Races: Freedom—Now (page title)". The Nation. TIME. 81 (20). May 17, 1963. pp. 23–27.

[American] history, as Baldwin sees it, is an unending story of man's inhumanity to man, of the white's refusal to see the black simply as another human being, of the white man's delusions and the Negro's demoralization.

- ^ Leeming, James Baldwin: A Biography (1994).

- ^ "Why James Baldwin's FBI File Was 1,884 Pages". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "A Brando timeline". Chicago Sun-Times. July 3, 2004. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ Leighton, Jared E. (May 2013), Freedom Indivisible: Gays and Lesbians in the African American Civil Rights Movement, Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History., University of Nebraska, retrieved July 21, 2021

- ^ Williams, Lena (June 28, 1993). "Blacks Rejecting Gay Rights As a Battle Equal to Theirs". The New York Times.

- ^ Baldwin FBI File, 1225, 104; Reider, Word of the Lord Is upon Me, 92.

- ^ Anderson, Gary L., and Kathryn G. Herr. "Baldwin, James (1924–1987)." Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice. ed. 2007. Print.

- ^ Mumford, Kevin (2014). Not Straight, Not White: Black Gay Men from the March on Washington to the AIDS Crisis. University of North Carolina Press. p. 25. ISBN 9781469628073.

- ^ Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities. "James Baldwin". Robert Penn Warren's Who Speaks for the Negro? Archive. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Lecture at UC Berkeley". Archived from the original on October 29, 2021.

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest", January 30, 1968, New York Post.

- ^ Leeming, David A. (1994). James Baldwin: A Biography. Knopf. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-394-57708-1. OCLC 28631289.

- ^ Michelle M. Wright, "'Alas, Poor Richard!': Transatlantic Baldwin, The Politics of Forgetting, and the Project of Modernity", Dwight A. McBride (ed.), James Baldwin Now, New York University Press, 1999, p. 208.

- ^ "Baldwin Reflections". The New York Times.

- ^ Baldwin, James; Buckley, William F. (March 7, 1965). "The American Dream" (PDF). The New York Times. pp. 32+. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ James Baldwin Debates William F. Buckley (1965) on YouTube

- ^ Winston Wilde, Legacies of Love, p. 93.

- ^ "Lucien Jean Happersberger". Find a Grave. May 13, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Diane (June 6, 1963). "Miss Hansberry and Bobby K". The Village Voice. VIII (33). Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ Brustein, Robert (December 17, 1964). "Everybody Knows My Name". New York Review of Books.

Nothing Personal pretends to be a ruthless indictment of contemporary America, but the people likely to buy this extravagant volume are the subscribers to fashion magazines, while the moralistic authors of the work are themselves pretty fashionable, affluent, and chic.

- ^ Angelou, Maya (December 20, 1987). "A brother's love". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Morrison, Toni (December 20, 1987). "Life in His Language". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ James Baldwin Biography, accessed December 2, 2010.

- ^ "James Baldwin: His Voice Remembered", The New York Times, December 20, 1987.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "James Baldwin". Books and Writers. Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010.

- ^ "James Baldwin, the Writer, Dies in France at 63", The New York Times, December 1, 1987.

- ^ Weatherby, W. J., James Baldwin: Artist on Fire, pp. 367–372.

- ^ Out, 14, Here Publishing, February 2006, p. 32, ISSN 1062-7928,

Baldwin died of stomach cancer in St. Paul de Vence, France, on December 1, 1987.

- ^ Daniels, Lee A. (December 2, 1987), "James Baldwin, Eloquent Writer In Behalf of Civil Rights, Is Dead", The New York Times.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, redn: 2 (Kindle Location 2290). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Farber, Jules B. (2016). James Baldwin: Escape from America, Exile in Provence. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 9781455620951.

- ^ a b "McGraw-Hill Drops Baldwin Suit". The New York Times, May 19, 1990.

- ^ Young, Deborah, "'I Am Not Your Negro': Film Review | TIFF 2016". The Hollywood Reporter, September 20, 2016.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2007). James Baldwin. Infobase Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7910-9365-8.

- ^ Pinckney, Darryl (April 4, 2013). "On James Baldwin". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ The Chronicle April 12, 1987, p. 6

- ^ Oler, Tammy (October 31, 2019). "57 Champions of Queer Feminism, All Name-Dropped in One Impossibly Catchy Song". Slate Magazine.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ Victor Salvo // The Legacy Project. "2012 INDUCTEES".

- ^ Boyd, Herb (July 31, 2014). "James Baldwin gets his 'Place' in Harlem". The Amsterdam News. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "THE YEAR OF JAMES BALDWIN: A 90TH BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION | NAMING OF "JAMES BALDWIN PLACE" IN HARLEM". Columbia University School of Fine Arts. July 24, 2014. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ Shelter, Scott (March 14, 2016). "The Rainbow Honor Walk: San Francisco's LGBT Walk of Fame". Quirky Travel Guy. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "Castro's Rainbow Honor Walk Dedicated Today: SFist". SFist - San Francisco News, Restaurants, Events, & Sports. September 2, 2014. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ Carnivele, Gary (July 2, 2016). "Second LGBT Honorees Selected for San Francisco's Rainbow Honor Walk". We The People. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Moore, Talia (December 24, 2015). "Students Seek More Support From the University in an Effort to Maintain a Socially Just Identity". The New School Free Press. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Timberg, Scott (February 23, 2017). "30 years after his death, James Baldwin is having a new pop culture moment". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Six New York City locations dedicated as LGBTQ landmarks". TheHill. June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ "Six historical New York City LGBTQ sites given landmark designation". Nbcnews.com. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ Glasses-Baker, Becca (June 27, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor unveiled at Stonewall Inn". metro.us. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ SDGLN, Timothy Rawles-Community Editor for (June 19, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor to be unveiled at historic Stonewall Inn". San Diego Gay and Lesbian News. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ "Groups seek names for Stonewall 50 honor wall". The Bay Area Reporter / B.A.R. Inc. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Stonewall 50". San Francisco Bay Times. April 3, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "L'écrivain James Baldwin va donner son nom à une future médiathèque de Paris". TÊTU (in French). January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ "James Baldwin - Artist". MacDowell.

- ^ Baldwin, James. October 1953. "Stranger in the Village (subscription required)." Harper's Magazine.

- ^ Baldwin, James. "Stranger in the Village (annotated)", edited by J. R. Garza. Genius.

- ^ "Richard Wright, tel que je l'ai connu" (French translation). Preuves. February 1961.

- ^ Baldwin, James (November 17, 1962). "Letter from a Region in My Mind". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Baldwin, James (December 1, 1962). "A Letter to My Nephew". The Progressive. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Baldwin, James. December 21, 1963. "A Talk to Teachers." The Saturday Review.

- ^ Baldwin, James. April 9, 1967. "Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They're Anti-White." New York Times Magazine. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Baldwin, James. 1961. Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son. US: Dial Press. ISBN 0-679-74473-8.

- ^ Baldwin, James. [2010] 2011. The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings, edited by R. Kenan. US: Vintage International. ISBN 978-0307275967. ASIN 0307275965.

- ^ Morrison, Toni, ed. 1998. Early Novels & Stories: Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni's Room, Another Country, Going to Meet the Man. Library of America. ISBN 978-1-883011-51-2.

- ^ Morrison, Toni, ed.1998. Collected Essays: Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, The Devil Finds Work, Other Essays. Library of America. ISBN 978-1-883011-52-9.

- ^ Baldwin, James. 2014. Jimmy's Blues and Other Poems. US: Beacon Press. ASIN 0807084867.

- ^ Pinckney, Darryl, ed. 2015. Later Novels: Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, If Beale Street Could Talk, Just Above My Head. Library of America. ISBN 978-1-59853-454-2.

- ^ Blint, Rich, notes and introduction. 2016. Baldwin for Our Times: Writings from James Baldwin for an Age of Sorrow and Struggle.

- ^ A Conversation With James Baldwin, retrieved September 25, 2020

- ^ "Take This Hammer - Bay Area Television Archive". diva.sfsu.edu. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ Debate: Baldwin vs. Buckley, retrieved September 25, 2020

- ^ Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris. Documentary, retrieved September 25, 2020

- ^ "Race, Political Struggle, Art and the Human Condition". Sam-network.org. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "'Assignment America; 119; Conversation with a Native Son,' from WNET features a television conversation between Baldwin and Maya Angelou".

- ^ "Pantechnicon; James Baldwin". American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

Further reading[]

Archival resources[]

- James Baldwin early manuscripts and papers, 1941–1945 (2.7 linear feet) are housed at Yale University Beinecke Library

- James Baldwin Papers, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Public Library (30.4 linear feet).

- Gerstner, David A. Queer Pollen: White Seduction, Black Male Homosexuality, and the Cinematic. University of Illinois Press, 2011. Chapter 2.

- Letters to David Moses at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

- James Baldwin Playboy Interview, archival materials held by Princeton University Library Special Collections

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Baldwin. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: James Baldwin |

- "A Conversation With James Baldwin", 1963-06-24, WGBH

- Transcript of interview with Dr. Kenneth Clark

- Works by James Baldwin at Open Library

- James Baldwin at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Altman, Elias, "Watered Whiskey: James Baldwin's Uncollected Writings", April 13, 2011. The Nation.

- Jordan Elgrably (Spring 1984). "James Baldwin, The Art of Fiction No. 78". Paris Review. Spring 1984 (91).

- Gwin, Minrose. "Southernspaces.org" March 11, 2008. Southern Spaces.

- James Baldwin talks about race, political struggle and the human condition at the Wheeler Hall, Berkeley, CA, in 1974

- James Baldwin Photographs and Papers, selected manuscripts, correspondence, and photographic portraits from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Comprehensive Resource of James Baldwin Information at the Wayback Machine (archived April 20, 2008)

- James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket, distributed by California Newsreel

- Baldwin's American Masters page

- "Writings of James Baldwin" from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Baldwin in the Literary Encyclopedia

- Audio files of speeches and interviews at UC Berkeley

- See Baldwin's 1963 film Take This Hammer, made with Richard O. Moore, about Blacks in San Francisco in the late 1950s.

- Video: Baldwin debate with William F. Buckley (via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center)

- Discussion with Afro-American Studies Dept. at UC Berkeley on YouTube

- Guardian Books "Author Page", with profile and links to further articles

- The James Baldwin Collective in Paris, France

- FBI files on James Baldwin

- FBI Docs, contains information about James Baldwin's destroyed FBI files and FBI files about him held by the National Archives

- A Look Inside James Baldwin's 1,884 Page FBI File

- James Baldwin at Biography.com

- Portrait of James Baldwin, 1964. [Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- Portrait of James Baldwin, 1985. [Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- 1924 births

- 1987 deaths

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American poets

- 20th-century scholars

- African-American academics

- African-American dramatists and playwrights

- African-American novelists

- African-American poets

- African-American short story writers

- American adoptees

- American expatriates in France

- American male dramatists and playwrights

- American male novelists

- American male poets

- American male short story writers

- American socialists

- American tax resisters

- Amherst College faculty

- Burials at Ferncliff Cemetery

- Deaths from cancer in France

- Deaths from stomach cancer

- DeWitt Clinton High School alumni

- George Polk Award recipients

- Hampshire College faculty

- LGBT African Americans

- LGBT dramatists and playwrights

- LGBT people from New York (state)

- American LGBT poets

- American gay writers

- American male essayists

- People from Harlem

- Postmodern writers

- Social critics

- Writers from Manhattan

- The New Yorker people

- The Nation (U.S. magazine) people

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American essayists

- Activists from New York (state)

- Novelists from New York (state)

- MacDowell Colony fellows

- New York (state) socialists

- African-American atheists

- American atheists

- 20th-century African-American people

- 20th-century LGBT people