Jockey Hollow

Wick House at Jockey Hollow (July 2015) | |

| |

| Coordinates | 40°45′41″N 74°32′33″W / 40.76139°N 74.54250°WCoordinates: 40°45′41″N 74°32′33″W / 40.76139°N 74.54250°W |

|---|---|

| Area | 1,307.49 acres (5.2912 km2) |

| Part of | Morristown National Historical Park (ID66000053[1]) |

| NJRHP No. | 3381[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Designated CP | October 15, 2000 |

| Designated NJRHP | May 27, 1971 |

Jockey Hollow, also known as Wick House and Wick Hall, was the traditional Wick family estate in New Jersey. Throughout the Revolutionary War, it was used by the Continental Army as its main winter encampment, and it housed the entire Continental Army during the Winter at Jockey Hollow, the harshest winter of the War, from December 1779 to June 1780.

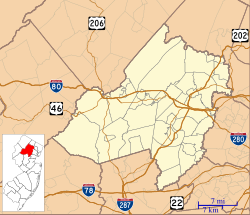

It is located in Harding Township and Mendham Township, in Morris County, New Jersey. Since 1933, the Wick House has been part of Morristown National Historical Park in Morristown, New Jersey. Morristown National Historical Park is administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.[3]

American Revolutionary War[]

During the Revolutionary War, Henry Wick owned Jockey Hollow, which by then consisted of 1400 acres of timber and open field. He was also the Captain of the Morris County Cavalry, whose duty it was to protect Governor Livingston, the Privy Council, and the New Jersey government. For this reason, the Wick family was considered the ideal family to house the Army. The Wick estate was considered the ideal location, because the elevation of Jockey Hollow was several hundred feet above the British to the east. The mountainous range also allowed soldiers to detect British movement.[4] During the winter of 1779–1780, nearly 600 acres of timber on Jockey Hollow were cut down by the soldiers to be used for the construction of huts and as firewood.[5]

Army encampment[]

Strategically, the Wick family were considered by the officers of the Continental Army to be one of the most reliable and patriotic families in America, so the Army never had any trouble quartering there, nor did the Wick family ever require compensation for the use of their land, which was especially important to Congress. The Continental Army had wintered there in 1776-77 following George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River and the subsequent American victories at Trenton and Princeton. One fourth of the Army died from smallpox or dysentery. During that Winter, the Wicks hosted Captain Joseph Bloomfield.

Jockey Hollow had hosted prominent officers before the winter of 1779–1780. Alexander Hamilton was likely quartered at the Wick House at least once during the War. The Wicks would use one side of the house, and gave the other to the officers who were quartered with them, and the Wicks would share the kitchen and dining room with the officers.

The Winter at Jockey Hollow[]

During the Winter of 1779–1780, the Wicks housed General Arthur St. Clair, who was then commander of the Pennsylvania Line, and several of his aides.

On October 17, 1779, the entire Continental Army, consisting of 13,000 men, encamped for the winter at Jockey Hollow. Soldiers camped at this location until June 1780, during which time they endured some of the harshest conditions of the war.[6] In the days of horsepower, this was considered an impregnable redoubt. Another reason why the location was chosen was because the surrounding area held citizens, like the Wick family, who were the strongest patriots in the region and the most sympathetic to the rebel cause.[4] The region was also home to many Huguenots, like Joshua Guerin, whose house is still preserved at the Park, but is inaccessible to Park visitors.

The Winter at Jockey Hollow was the worst winter of the war, even worse than the Winter at Valley Forge two years before.[7] Twelve men often shared one of over one thousand simple huts built in Jockey Hollow to house the Army.[6] Desertions were frequent. The entire Pennsylvania Line successfully mutinied, and later 200 New Jersey soldiers attempted to emulate them. Several of the ringleaders of the latter were hanged.[8]

The Legend of Tempe Wick[]

On December 21, 1780, Henry Wick died at Jockey Hollow. In January 1781, the Pennsylvania soldiers under the command of General Anthony Wayne mutinied. The soldiers intended to gather food and other supplies, including horses. They supposedly intended to travel south to Philadelphia to march on Congress. They demanded higher pay and better living conditions for soldiers. Instead of heading south to Philadelphia, the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania negotiated with them, and the mutiny ended peacefully, and many of the soldiers agreed to stay in the army. During that same winter, Mary Wick, the widow of Henry Wick, sent her daughter, Temperance Wick, known locally as Tempe, to get her brother-in-law, Dr. Leddel. Upon returning on her horse, Tempe was stopped by several soldiers and ordered to dismount and give them her horse. Tempe pretended to dismount, but tricked the soldiers, and escaped with her horse. When she returned to Jockey Hollow, she hid the horse in her bedroom using a feather bed to muffle the sound of the horses hooves. Shortly thereafter, the soldiers came looking for the horse and searched the barn and in the woods surrounding the home, and never imagined that the horse was hidden inside the house. In one version of this legend, the horse remained hidden in the home for three weeks. This inspired Ann Rinaldi's famous novel, A Ride Into Morning, which combines several versions of the story together, told from the perspective of Mary Cooper, a cousin of Tempe Wick, who lived at Jockey Hollow during the Winter at Jockey Hollow.

Other versions of the story include Tempe Wick saving General Washington from mutineers during the Pennsylvania Line Mutiny, passing letters through British lines, and acting as a spy. However, these versions of the story are generally regarded as erroneous.[9]

Wick garden[]

Supposedly, the Wick garden at Jockey Hollow was the place where the Marquis de Lafayette delivered to General George Washington the news that the French were sending a large fleet and army to reinforce the Continental Army in America. The French intervention would be the turning point of the War.

The Wick garden is maintained by the Northern New Jersey unit of . It and the Wick House, are considered one of New Jersey's primary tourist attractions.

Soldier housing[]

Soldiers had to build their own huts including surrounding trenches for drainage. The huts, made of log, were 14 by 16 feet (4.3 by 4.9 m) and 6.5 feet (2.0 m) high. Twelve men often shared one of over one thousand simple huts built in Jockey Hollow to house the army.[6] Inside the huts soldiers had a fireplace for warmth and cooking. To create a floor they packed the ground for an earthen floor. Soldiers also had to make their own furniture, including bunks and tables. Their bunks got covered with straw and each soldier was given one blanket. Soldiers huts were about 2 to 3 ft (50–100 cm) apart, with three rows of eight huts for each regiment. By 1780, soldiers had built about 1,200 huts in Jockey Hollow.[4]

Several monuments are dedicated and built over the mass graves of the soldiers who died at Jockey Hollow.

Facilities[]

- Jockey Hollow Visitor Center

- Wick House: Park employee in period dress.

Activities[]

- Biking

- Bird Watching

- Hiking

- Interpretive Programs

- Snow Skiing

- Children's Junior Ranger Program

See also[]

- New Jersey Brigade Encampment Site - Used by the New Jersey Brigade during the same winter encampment

- Temperance Wick

- William W. Wick

- Hilton Wick

- Valley Forge

Notes[]

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places – Morris County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection – Historic Preservation Office. November 28, 2016. p. 6.

- ^ "Morristown National Historical Park". National Park Service.

- ^ a b c Adams, Hugh W., Morristown National Historic Park. Christine Retz. New Jersey: Washington Association of New Jersey, 1982

- ^ http://rt23.com/american_revolution/wick_house.shtml

- ^ a b c National Park Service, Morristown Pamphlet. Morristown National Historic Park, 2007

- ^ Tolson, Jay (July 7–14, 2008). How Washington's Savvy Won the Day. US News and World Report.

- ^ Flexner, James Thomas (April 1984). "Washington "The Indispensable Man"": 154. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ http://mentalfloss.com/article/63264/5-legends-americas-national-parks

External links[]

- American Revolutionary War sites

- Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in New Jersey

- Harding Township, New Jersey

- Historic house museums in New Jersey

- American Revolutionary War museums in New Jersey

- Museums in Morristown, New Jersey

- Morristown National Historical Park

- Parks in Morris County, New Jersey

- National Register of Historic Places in Morris County, New Jersey

- Houses in Morris County, New Jersey

- American Revolution on the National Register of Historic Places