Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th Senior Officer of the United States Army | |

| In office April 13, 1792 – December 15, 1796 | |

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Arthur St. Clair |

| Succeeded by | James Wilkinson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1791 – March 21, 1792 | |

| Preceded by | James Jackson |

| Succeeded by | John Milledge |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 1, 1745 Easttown Township, Province of Pennsylvania |

| Died | December 15, 1796 (aged 51) Fort Presque Isle, Erie, Pennsylvania |

| Resting place | St. David's Episcopal Church, Radnor |

| Political party | Anti-Administration party |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Penrose |

| Children | Margretta Wayne, Isaac Wayne |

| Relatives | Isaac Wayne (father) Samuel Van Leer (brother in-law) |

| Occupation | Soldier |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Mad Anthony |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1775–1783 1792–1796 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer and statesman of Irish descent. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his military exploits and fiery personality quickly earned him promotion to brigadier general and the nickname "Mad Anthony". He later served as the Senior Officer of the Army on the Ohio Country frontier and led the Legion of the United States.

Wayne was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and worked as a tanner and surveyor after attending the College of Philadelphia. He was elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly and helped raise a Pennsylvania militia unit in 1775. During the Revolutionary War, he served in the Invasion of Quebec, the Philadelphia campaign, and the Yorktown campaign. His reputation suffered due to his defeat in the Battle of Paoli, but he won wide praise for his leadership in the 1779 Battle of Stony Point. He was promoted to Major General in 1783 but retired from the Continental Army soon after. Anthony Wayne was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati of the State of Georgia.[1] In 1780, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[2]

After the war, Wayne settled in Georgia on land that had been granted to him for his military service. He briefly represented Georgia in the House of Representatives, then returned to the Army to accept command of U.S. forces in the Northwest Indian War. His forces defeated the Western Confederacy, an alliance of several Indian tribes, at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers, and he masterminded the Treaty of Greenville which ended the war.

Wayne died in 1796 in Erie, Pennsylvania, while on active duty.

Early life[]

Wayne was one of four children born to Isaac Wayne, who had immigrated to Easttown Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania, from Ireland, and Elizabeth Iddings Wayne. He was part of a Protestant Anglo-Irish family; his grandfather was a veteran of the Battle of the Boyne where he fought for the Williamite side.[3] Wayne was born on January 1, 1745, on his family's Waynesborough estate.[4] He was educated as a surveyor at his uncle's private academy in Philadelphia as well as at the College of Philadelphia, although he did not earn a degree. In 1765, Benjamin Franklin sent him and some associates to work for a year surveying land granted in Nova Scotia, and he assisted with starting a settlement the following year at The Township of Monckton.[5] In 1767, he returned to work in his father's tannery while continuing work as a surveyor. He became a prominent figure in Chester County and served in the Pennsylvania legislature from 1774 to 1780. His sister Hannah married his neighbor and fellow United States Army Officer Samuel Van Leer.[6]

He married Mary Penrose in 1766 and they had two children. Their daughter Margretta was born in 1770 and their son Isaac Wayne was born in 1772 and later became a Representative from Pennsylvania.[7] Wayne's marriage with Mary was conflicted as he would often ignore her and have romantic relationships with other women, including Mary Vining, a wealthy woman in Delaware.[8]

American Revolution[]

Wayne raised a militia unit in 1775 and became colonel of the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment in 1776. He and his regiment were part of the Continental Army's unsuccessful invasion of Canada where he was sent to aid Benedict Arnold. Wayne commanded a successful rear-guard action at the Battle of Trois-Rivières and then led the distressed forces on Lake Champlain at Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. His service led to his promotion to brigadier general on February 21, 1777. According to historians, Wayne earned the name "Mad Anthony" due to his angry temperament, specifically during an incident when he severely punished a skilled informant for being drunk.[9]

On September 11, 1777, Wayne commanded the Pennsylvania Line at the Battle of Brandywine where they held off General Wilhelm von Knyphausen in order to protect the American right flank. The two forces fought for three hours until the American line withdrew and Wayne was ordered to retreat.[10] He was then ordered to harass the British rear in order to slow General Howe's advance towards Pennsylvania. Wayne's camp was attacked on the night of September 20–21 in the Battle of Paoli. General Charles Grey had ordered his men to remove their flints and attack with bayonets in order to keep their assault secret.[11] The battle earned Grey the sobriquet of "General Flint", but Wayne's own reputation was tarnished by the significant American losses, and he demanded a formal inquiry in order to clear his name.

On October 4, 1777, Wayne again led his forces against the British in the Battle of Germantown. His soldiers pushed ahead of other units, and the British "pushed on with their Bayonets—and took Ample Vengeance" as they retreated, according to Wayne's report.[12] Generals Wayne and Sullivan advanced too quickly, however, and became entrapped when they were two miles (3.2 km) ahead of other American units. They retreated as General Howe arrived to re-form the British line. General Wayne was again ordered to hold off the British and cover the rear of the retreating body.

After winter quarters at Valley Forge, Wayne led the attack at the 1778 Battle of Monmouth, where his forces were abandoned by General Charles Lee and were pinned down by a numerically superior British force. Wayne held out until relieved by reinforcements sent by Washington. He then re-formed his troops and continued to fight.[13] The body of Lt. Colonel Henry Monckton was discovered by the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, and a legend grew that he had died fighting Wayne.

In July 1779, Washington named Wayne to command the Corps of Light Infantry, a temporary unit of four regiments of light infantry companies drawn from all the regiments in the Main Army. His successful attack on British positions in the Battle of Stony Point was the highlight of his Revolutionary War service. On July 16, 1779, he replicated the bold attack used against him at Paoli and personally led a nighttime bayonet attack lasting 30 minutes. His three columns of about 1,500 light infantry stormed and captured British fortifications at Stony Point, a cliff-side redoubt commanding the southern Hudson River. The battle ended with around 550 prisoners taken, with fewer than 100 casualties for Wayne's forces. The success of this operation provided a small boost to the morale of the army, which had suffered a series of military defeats, and the Continental Congress awarded him a medal for the victory.[14][15]

On July 21, 1780, Washington sent Wayne with two Pennsylvania brigades and four cannons to destroy a blockhouse at Bulls Ferry opposite New York City in the Battle of Bull's Ferry. Wayne's troops were unable to capture the position, suffering 64 casualties while inflicting 21 on the Loyalist defenders.[16]

On January 1, 1781, Wayne served as commanding officer of the Pennsylvania Line of the Continental Army when pay and condition concerns led to the Pennsylvania Line Mutiny, one of the most serious of the war. He successfully resolved the mutiny by dismissing about half the line. He returned the Pennsylvania Line to full strength by May 1781. This delayed his departure to Virginia, however, where he had been sent to assist the Marquis de Lafayette against British forces operating there, and the Line's departure was delayed once more when the men complained about being paid in the nearly worthless Continental currency.

In Virginia, Wayne led a small scouting force of 500 at the 1781 Battle of Green Spring to determine the location of Lord Charles Cornwallis, and they fell into a trap. Once again, Wayne held out against numerically superior forces until reinforced by Major John Wyllys. Cornwallis then attacked, and Wayne[17] led a bayonet charge against the British forces and then retreated in good order as night set in. This increased his reputation as a bold commander.

After the British under General Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Wayne went farther south and disbanded the British alliance with Indian tribes in Georgia. He then negotiated peace treaties with both the Creeks and the Cherokees, for which Georgia rewarded him with a large rice plantation. He was promoted to major general on October 10, 1783.

Civilian life[]

Rice plantations[]

After the war, Wayne returned to Pennsylvania and served in the state legislature for a year in 1784. He then moved to Georgia and settled upon two rice plantations with an area of 1,134 acres (459 hectares) that had been granted to him for his military service.[18] The plantations, Richmond and Kew, were situated on the Savannah River and were confiscated from British loyalist Alexander Wright, son of governor of the Province of Georgia James Wright.[19] Wayne would then purchase slaves from Adam Tunno, making the slaves farm and make various repairs on the plantations.[20] Fellow general and friend Nathanael Greene was also gifted the Mulberry Grove Plantation that was worked by slaves.[21] Rumors of a relationship between Wayne and Greene's wife Catherine caused tension between the two generals.[21] While Wayne's wife and family maintained their lives in Pennsylvania, Wayne became a Georgia citizen in November 1788.[22] Wayne's plantations were ultimately unsuccessful as he made poor business decisions and acquired a large debt to Tunno, Samuel Potts and others, later begging various acquaintances to assist him with making payments.[8][20][22]

Political career[]

Initially a supporter of democracy, Wayne ultimately believed that the United States should be an aristocracy, supporting the idea of a centralized government controlled by the "aristocratick".[8] He would join the Federalist Party believing that his status secured him a position among the American elite in the party.[8] Wayne was a delegate to the state convention that ratified the United States Constitution in 1788. In 1791, he served a year in the Second United States Congress as a Representative of Georgia's 1st congressional district.[23] A House committee determined that electoral fraud had been committed in the 1790 election, and Wayne lost his seat over his residency qualifications. A special election was held on July 9, 1792, sending John Milledge to fill Wayne's vacant seat, and Wayne declined to run for re-election in 1792.[24]

Later military career[]

At a time of his life when Wayne experienced a shameful political and personal status, President George Washington recalled Wayne from civilian life in order to lead an expedition in the Northwest Indian War.[14] The war had been a disaster for the United States up till that point, particularly with the news of St. Clair's Defeat. Many American Indians in the Northwest Territory had sided with the British in the Revolutionary War, but the British had ceded any sovereignty over the land to the United States in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. The Indians living in the region quickly became embroiled in conflicts while defending their land from American settlers who were flooding into the region in the aftermath of the war. The Western Confederacy achieved major victories in 1790 and 1791 under the leadership of Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Little Turtle of the Miami tribe. They were encouraged and supplied by the British, who had refused to evacuate their fortifications in the region despite having agreed to do so in the Treaty of Paris, pointing to American refusal to honor the debt-agreements that they had agreed to pay as signs that the Treaty was not yet applicable.

Washington placed Wayne in command of a newly formed military force called the "Legion of the United States", and Wayne established a basic training facility at Legionville to prepare professional soldiers for his force. This was the first attempt to provide basic training for regular Army recruits, and Legionville was the first facility established expressly for this purpose. Wayne then dispatched a force to Ohio to establish Fort Recovery as a base of operations at the location of St. Clair's Defeat, and the fort became a magnet for military skirmishes in the summer of 1794. Wayne's army continued north, building strategically defensive forts ahead of the main force.

A tree fell on Wayne's tent on August 3, 1794, at Fort Adams in northern Mercer County. He was knocked unconscious, but he recovered sufficiently to resume the march the next day to the newly built Fort Defiance.[25] On August 20, 1794, he mounted an assault on the Indian confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in Maumee, Ohio, which was a decisive victory for the U.S. forces, effectively ending the war. Following the battle, Wayne used Fort Defiance as a base of operations, ordering his troops to destroy Native American crops and villages within a radius of 50 miles (80 km) around the fort.[26] Wayne then continued to Kekionga marching down the Maumee River, writing to Henry Knox that his troops were "laying waste [to] the villages and corn-fields" of evacuating natives.[14] After arriving at Kekionga, Wayne oversaw the construction of Fort Wayne.

Wayne then negotiated the Treaty of Greenville between the tribal confederacy — which had experienced a difficult winter – and the United States, which was signed on August 3, 1795. The treaty gave most of Ohio to the United States and cleared the way for the state to enter the Union in 1803. At the meetings, Wayne promised the land of "Indiana", the remaining land to the west, to remain Indian forever.[14] In the subsequent decades, settlers would continue pushing natives further westward, with the Miami people later saying that fewer than one-hundred adults survived twenty years after the treaty.[14]

Wayne died of complications from gout on December 15, 1796, during a return trip to Pennsylvania from a military post in Detroit. He was buried at Fort Presque Isle where the modern Wayne Blockhouse stands. His son Isaac Wayne disinterred the body in 1809 and had the corpse boiled to remove the surviving flesh from the bones.[27] He then placed the bones into two saddlebags and relocated them to the family plot in the graveyard of St. David's Episcopal Church in Wayne, Pennsylvania.[28] The other remains were reburied and discovered in 1878, giving General Wayne two known grave sites.[27] There is a legend which claims that many bones were lost along the roadway which encompasses much of U.S. Route 322, and that his ghost wanders the highway on January 1 (Wayne's birthday) searching for his lost bones.[29]

Legacy[]

The door in Senate room 128 features a 19th-century fresco painting by Constantino Brumidi named “Storming at Stonypoint, General Wayne wounded in the head carried to the fort."[30] On September 14, 1929, the U.S. Post Office issued a stamp honoring General Wayne which commemorated the 135th anniversary of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The post office issued a series of stamps often referred to as the "Two Cent Reds" by collectors, most of them issued to commemorate the 150th anniversaries of the many events that occurred during the American Revolution. The stamp shows Bruce Saville's Battle of Fallen Timbers Monument.

More recently Wayne's legacy has been criticized due to his actions against Native Americans. According to Indian Country Today, "It was General Mad Anthony Wayne who led the first wave" of Indian removal in the United States, writing that the Miami people "maintain that celebrating Wayne glosses over and ignores his role in the genocide of Native Americans".[31] At a February 2019 city council meeting in Fort Wayne, Indiana, the 6-3 approval of an Anthony Wayne Day was criticized by City Councilman Glynn Hines, who stated Wayne's actions were part of a "genocide of Native Americans".[14][31][32]

Wayne's notable descendants include:

- Isaac Wayne (1772–1852), member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, son of General "Mad" Anthony Wayne, and grandson of Isaac Wayne[33]

- Captain William Evans Wayne (1828-1901), fought in the Civil War for the Union[34]

The Storming of Stony Point, 1779 by Constantino Brumidi (1871) in room S-128 of the United States Capitol

Battle of Fallen Timbers, commemorative issue of 1928, 2¢

His home, Waynesborough in Paoli, Pennsylvania

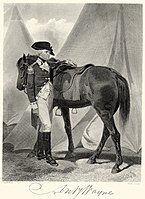

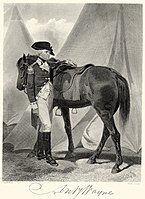

Steel engraving of Anthony Wayne by Alonza Chappel

His grave at St. David's Episcopal Church (Radnor, Pennsylvania)

Anthony Wayne Bridge (Toledo, Ohio)

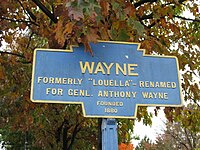

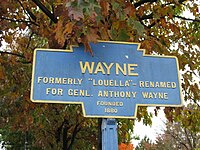

Keystone Marker in Wayne, Pennsylvania, named for General Wayne

Wayne County Building (Detroit, Michigan) pediment

Wayne State University. Detroit, Michigan, Maccabees Building

See also[]

Biography portal

Biography portal

Notes[]

- ^ Aimone, Alan Conrad (2005). "New York State Society of the Cincinnati: Biographies of Original Members and Other Continental Officers (review)". The Journal of Military History. 69 (1): 231–232. doi:10.1353/jmh.2005.0002. ISSN 1543-7795. S2CID 162248285.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Caust-Ellenbogen, Celia. ""Mad" Anthony Wayne". Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Nelson, 5–6

- ^ Labaree, 345-50

- ^ "Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society".

- ^ Anthony and Mary (Penrose) Wayne Family Bible

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne, Soldier of the Early Republic. Indiana University Press. pp. 4–5, 208.

- ^ Nelson, Paul D. (1985). Anthony Wayne, Soldier of the Early Republic. Indiana University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0253307514.

- ^ Nelson, 52

- ^ Nelson, 55–58

- ^ Nelson, 60

- ^ Lancaster, 195–97

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Savage, Charlie (July 31, 2020). "When the Culture Wars Hit Fort Wayne". POLITICO. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Anthony Wayne Encyclopedia Britannica Entry".

- ^ Boatner, 119–20

- ^ Lancaster, 319–22

- ^ "Founders Online: May [1791]". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Rogers Jr., George C. (April 1988). "A Social Portrait of the South at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century". Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. American Antiquarian Society. 98, Part 1: 35–49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne, Soldier of the Early Republic. Indiana University Press. pp. 187–208. ISBN 0253307511.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "MULBERRY GROVE FROM THE REVOLUTION TO THE PRESENT TIME". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Georgia Historical Society. 23 (4): 315–336. December 1939.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "RICHMOND OAKGROVE PLANTATION: Part II". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Georgia Historical Society. 24 (2): 124–144. June 1940.

- ^ "WAYNE, Anthony, (1745–1796)". bioguide.congress.gov.

- ^ United States Congressional Elections, 1788–1997: The Official Results confirms the seat was declared vacant on March 21, 1792.

- ^ Carter, 133

- ^ "Defiance, Ohio - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Wayne Buried in Two Places". Paoli Battlefield. Independence Hall Association. Retrieved October 16, 2019 – via ushistory.org.

- ^ Hugh T. Harrington and Lisa A. Ennis. "Mad" Anthony Wayne: His Body Did Not Rest in Peace, citing History of Erie County, Pennsylvania, vol. 1. pp. 211–12. Warner, Beers & Co., Chicago. 1884.

- ^ Wood, Maureen & Kolek, Ron (2010). A Ghost a Day: 365 True Tales of the Spectral, Supernatural, and Just Plain Scary!, p. 1. Adams Media.

- ^ "8 "Gems of the Capitol"". Constantino Brumidi: Artist of the Capitol (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1998. pp. 106, 109. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pember, Mary Annette. "Celebrating (not) Mad Wayne Day". Indian Country Today. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Tran, Louie (March 2, 2019). "'If it wasn't for Anthony Wayne, there may not be a United States of America'; City Council officials share the importance of Anthony Wayne Day". WPTA. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Anthony Wayne Encyclopedia Britannica Entry".

- ^ "Captain Williams Evans Wayne".

References[]

- Allen, William B. (1872). A History of Kentucky: Embracing Gleanings, Reminiscences, Antiquities, Natural Curiosities, Statistics, and Biographical Sketches of Pioneers, Soldiers, Jurists, Lawyers, Statesmen, Divines, Mechanics, Farmers, Merchants, and Other Leading Men, of All Occupations and Pursuits. Bradley & Gilbert. pp. 46–47. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Boatner, Mark M., III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis (1987). The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01318-2.

- Dubin, Michael J (1998). United States Congressional Elections, 1788–1997: The Official Results of the Elections of the 1st through 105th Congresses. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company. ISBN 0-7864-0283-0.

- Knopf, Richard C. (ed) (1960). Anthony Wayne: A Name in Arms. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822975342.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Labaree, Leonard W. (ed.) (1968). The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. 12. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Lancaster, Bruce (1971). The American Revolution. New York: American Heritage Books. ISBN 0-618-12739-9.

- Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne. Soldier of the Early Republic. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-30751-1.

- Pleasants, Henry; Delaware County Historical Society (1907). History of Old St. David's Church Radnor, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. John C Winston Co. p. 206.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anthony Wayne. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anthony Wayne |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Anthony Wayne. |

- Anthony Wayne and the Battle of Fallen Timbers from The Army Historical Foundation

- General Anthony Wayne

- Anthony Wayne family papers. William L. Clements Library.

- National Park Service Museum Collection: American Revolutionary War Exhibit, Wayne portrait & bio

- Maumee Valley Heritage Corridor

- Anthony Wayne – The Man Buried in Two Places

- 1745 births

- 1796 deaths

- American slave owners

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American people of the Northwest Indian War

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Continental Army generals

- Continental Army officers from Pennsylvania

- History of Fort Wayne, Indiana

- Members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Georgia (U.S. state)

- People from Chester County, Pennsylvania

- People from Paoli, Pennsylvania

- History of Pennsylvania

- People of colonial Pennsylvania

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Revolution

- United States Army generals

- University of Pennsylvania alumni

- Commanding Generals of the United States Army

- 18th-century American politicians

- Members of the United States House of Representatives removed by contest