St. Clair's defeat

| Battle of the Wabash | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Northwest Indian War | |||||||

Arthur St. Clair | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Western Confederacy |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, Buckongahelas |

Arthur St. Clair, Richard Butler † William Darke | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,100 | 1,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

21 killed 40 wounded total: 61 |

632 soldiers killed or captured 264 soldiers wounded 24 workers killed, 13 workers wounded total: 933 (not including women and children) | ||||||

St. Clair's defeat, also known as the Battle of the Wabash, the Battle of Wabash River or the Battle of a Thousand Slain,[1] was a battle fought on 4 November 1791 in the Northwest Territory of the United States of America. The U.S. Army faced the Western Confederacy of Native Americans, as part of the Northwest Indian War. It was "the most decisive defeat in the history of the American military"[2] and its largest defeat ever by Native Americans.[3]

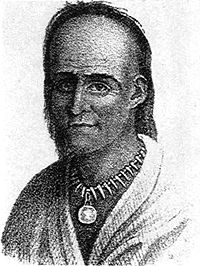

The Native Americans were led by Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees, and Buckongahelas of the Delawares (Lenape). The war party numbered more than 1,000 warriors, including many Potawatomis from eastern Michigan and the Saint Joseph. The opposing force of about 1,000 Americans was led by General Arthur St. Clair. The forces of the American Indian confederacy attacked at dawn, taking St. Clair's men by surprise. Of the 1,000 officers and men that St. Clair led into battle, only 24 escaped unharmed. As a result, President George Washington forced St. Clair to resign his post, and Congress initiated its first investigation of the executive branch.[4]

Background[]

In the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War, Great Britain recognized United States sovereignty of all the land east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes. The native tribes in the Old Northwest, however, were not parties to this treaty and many of them, especially leaders such as Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, refused to recognize American claims to the area northwest of the Ohio River. The young United States government, deeply in debt following the Revolutionary War and lacking the authority to tax under the Articles of Confederation, planned to raise funds via the methodical sale of land in the Northwest Territory. This plan necessarily called for the removal of both Native American villages and squatters.[5] During the mid and late 1780s, American settlers in Kentucky and travelers on and north of the river suffered approximately 1,500 deaths during the ongoing hostilities, in which white settlers often retaliated against Indians. The cycle of violence threatened to deter settlement of the newly acquired territory, so John Cleves Symmes and Jonathan Dayton petitioned President Washington and his Secretary of War, Henry Knox, to use military force to crush the Miami.[6]

A force of 1,453 men (320 regulars from the First American Regiment and 1,133 militia) under Brigadier General Josiah Harmar marched northwards from Fort Washington on the Ohio River at 10:00 a.m. on 7 October 1790. The campaign ended in disaster for the United States. On 19–22 October, near Kekionga (present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana), Harmar committed detachments that were ambushed by Native American forces defending their own territory. On three separate occasions, Harmar failed to reinforce the detachments. Suffering more than 200 casualties, as well as a loss of a third of his packhorses, Harmar ordered a retreat back to Ft. Washington.[7] Estimates of total Native casualties, killed and wounded, range from 120 to 150.

President George Washington then ordered General Arthur St. Clair, who served both as governor of the Northwest Territory and as a major general in the Army, to mount a more vigorous effort by summer 1791. Congress agreed to raise a second regiment of Regular soldiers for six months,[8] but it later reduced soldiers' pay. The demoralized First Regiment was soon reduced to 299 soldiers, while the new Second Regiment was able to recruit only half of its authorized soldiers.[8] St. Clair was forced to augment his Army with Kentucky militia as well as two regiments (five battalions) of six-month levies.[9]

Command structure[]

The Native American forces were primarily led by Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnee, and Buckongahelas of the Lenape.[10] The command structure may have been less formal than U.S. forces, and has been a source of debate. Both Blue Jacket and Little Turtle later claimed to have been in overall command of the united forces.[11] John Norton claimed that when the battle began, the Shawnee took the lead.[10] Little Turtle is often credited for the victory, but this may have been due to the influence of his son-in-law, William Wells, who later served with the United States as an Indian Agent and interpreter.[12]

The United States command structure was as follows:[9]

US Army - Major General Arthur St. Clair

- 1st Infantry Regiment - Major Jean François Hamtramck (only part of the regiment under Captain Thomas Doyle was engaged)

- 2nd Infantry Regiment - Major Jonathan Hart [killed]

- Artillery Battalion - Major William Ferguson [killed]

US levies - Major General Richard Butler [killed]

- 1st Levy Regiment - Lieutenant Colonel William Darke

- 2nd Levy Regiment - Lieutenant Colonel George Gibson

Kentucky militia - Lieutenant Colonel William Oldham [Killed]

Campaign[]

Washington was adamant for St. Clair to move north in the summer months, but various logistics and supply problems greatly slowed his preparations in Fort Washington (now Cincinnati, Ohio). The new recruits were poorly trained and disciplined, the food supplies were substandard, and the horses were not only low in number, but also of poor quality. The expedition thus failed to set out until October 1791. Building supply posts as it advanced, the Army's objective was the town of Kekionga, the capital of the Miami tribe, near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana.

The Army under St. Clair included 600 regulars, 800 six-month conscripts, and 600 militia at its peak, a total of around 2,000 men.[14] Desertion took its toll and when the force finally got underway, it had dwindled to around 1,486 total men and some 200–250 camp followers (wives, children, laundresses, and prostitutes). Going was slow and discipline problems were severe; St. Clair, suffering from gout, had difficulty maintaining order, especially among the militia and the new levies. The force was constantly shadowed by Indians and skirmishes occasionally erupted. By the end of 2 November, through further desertion and illness, St. Clair's force had been whittled down to around 1,120, including the camp followers. While St. Clair's Army continued to lose soldiers, the Western Confederacy quickly added numbers. Buckongahelas led his 480 men to join the 700 warriors of Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, bringing the war party to more than one thousand warriors, including many Potawatomis from eastern Michigan and the Saint Joseph.

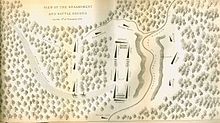

St. Clair had 52 officers and 868 enlisted and militia present for duty on 3 November. That day, the combined force camped on an elevated meadow, with the First Infantry and volunteers encamped on the opposite side of the river from the Kentucky militia camp, making it difficult to assist one another.[15] No defensive works were constructed, even though natives had been seen in the forest.[16] Major General Richard Butler sent a small detachment of soldiers under Captain Jacob Slough to capture some warriors who had harassed the camp. The detachment fired on a small party of Native Americans, but soon realized they were outnumbered.[17] They returned to the camp and reported that they believed an attack was imminent, but Butler did not send this report to St. Clair, nor increase the camp's defenses.[15]

Battle[]

On the evening of 3 November, St. Clair's force established a camp on a high hill near the present-day location of Fort Recovery, Ohio, near the headwaters of the Wabash River. A native force consisting of around 1,000 warriors, led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, established a large crescent surrounding the camp.[19] Here in the woods, they waited until dawn, when the men stacked their weapons and paraded to their morning meals.[16] Adjutant General Winthrop Sargent had just reprimanded the militia for failing to conduct reconnaissance patrols when the natives struck, surprising the Americans and overrunning their ground.

Little Turtle directed the first attack at the militia, who fled across a stream without their weapons. The regulars immediately broke their musket stacks, formed battle lines and fired a volley into the natives, forcing them back.[20] Little Turtle responded by flanking the regulars and closing in on them. The muskets and artillery were of poor quality, and had little effect on the Native warriors behind their cover.[21] Meanwhile, St. Clair's artillery was stationed on a nearby bluff and was wheeling into position when the gun crews were killed by native marksmen, and the survivors were forced to spike their guns.

Colonel William Darke ordered his battalion to fix bayonets and charge the main native position. Little Turtle's forces gave way and retreated to the woods, only to encircle Darke's battalion and destroy it.[22] The bayonet charge was tried numerous times with similar results and the U.S. forces eventually collapsed in disorder. St. Clair had three horses shot out from under him as he tried in vain to rally his men.

After three hours of fighting, St. Clair called together the remaining officers and, faced with total annihilation, decided to attempt one last bayonet charge to get through the native line and escape. Supplies and wounded were left in camp. As before, Little Turtle's Army allowed the bayonets to pass through, but this time the men ran for Fort Jefferson.[23] They were pursued by Indians for about three miles before the latter broke off pursuit and returned to loot the camp. Exact numbers of wounded are not known, but it has been reported that execution fires burned for several days afterwards.[23]

The casualty rate was the highest percentage ever suffered by a United States Army unit and included St. Clair's second in command, Richard Butler. Of the 52 officers engaged, 39 were killed and 7 wounded; around 88% of all officers had become casualties. After two hours St. Clair ordered a retreat, which quickly turned into a rout. "It was, in fact, a flight," St. Clair described a few days later in a letter to the Secretary of War. The American casualty rate among the soldiers, was 97.4 percent, including 632 of 920 killed (69%) and 264 wounded. Nearly all of the 200 camp followers were slaughtered, for a total of 832 Americans killed. Approximately one-quarter of the entire U.S. Army had been wiped out. Only 24 of the 920 officers and men engaged came out of it unscathed. The survivors included Benjamin Van Cleve and his uncle Robert Benham; van Cleve was one of the few who were unharmed. Native casualties were about 61, with at least 21 killed.

Historian William Hogeland calls the Native American victory "the high-water mark in resistance to white expansion. No comparable Indian victory would follow."[24] The next day the remnants of the force arrived at the nearest U.S. outpost, Fort Jefferson, and from there returned to Fort Washington.[25]

Aftermath[]

Native American response[]

The confederacy reveled in their triumph and war trophies, but most members of the force returned to their respective towns after the victory. The 1791 harvest had been insufficient in the region, and the warriors needed to hunt for Winter food stores.[26] A grand council was held on the banks of the Ottawa River to determine whether to continue the war against the United States or negotiate a peace from a strong position. The council delayed the final decision until a new grand council could be held the following year.[26]

Both Little Turtle and Blue Jacket claimed to have been in overall command of the native forces at the victory, causing resentment between the two men and their followers.[11]

British response[]

The British, surprised and delighted at the success of the natives they had been supporting and arming for years, stepped up their plans to create a pro-British Indian barrier state that would be closed to further settlement and encompass what was then known as the Northwest Territory, which spanned the American Midwestern region from Ohio into Minnesota.[27] The plans were developed in Canada, but in 1794, the government in London reversed course and decided it was necessary to gain American favor since a major war had broken out with France. London put the barrier state idea on hold and opened friendly negotiations with the Americans that led to the Jay Treaty of 1794. One provision was that the British acceded to American demands to remove their forts from American territory in Michigan and Wisconsin. The British, however, maintained their forts in Ontario from which they supplied munitions to the Natives living in the United States.[28]

American response[]

Fort Jefferson did not have adequate supplies for the remaining force under St. Clair, so those who could travel continued their retreat. Many wounded were left behind with no medicine and little food.[29] St. Clair sent a supply convoy and a hundred soldiers under Major David Ziegler from Fort Washington on 11 November.[30] He arrived at Fort Jefferson and found 116 survivors eating "horse flesh and green hides".[31] Charles Scott organized a relief party of Kentucky militia, but it disbanded at Fort Washington in late November with no action taken. Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson assumed command of the Second Regiment in January 1792 and led a supply convoy to Fort Jefferson. The detachment attempted to bury the dead and collect the missing cannons, but the task proved to be beyond it, with "upwards of six hundred bodies" at the battle site and at least 78 bodies along the road.[32]

News of the defeat reached the eastern states by late November. A French resident learned of the battle from Native Americans, and shared the news at Vincennes. From there, a traveler headed east sent word to Virginia Governor Henry Lee, along with an alarm from Charles Scott.[33]

St. Clair's official report was carried by Major Ebenezer Denny to Philadelphia. Henry Knox escorted Denny to President Washington on 20 December.[33] Washington was outraged when he received news of the defeat.[34] After cursing St. Clair, he told Tobias Lear, "General St. Clair shall have justice. I looked hastily through the dispatches, saw the whole disaster but not all the particulars."[35] St. Clair left Wilkinson in charge of Fort Washington[35] and arrived in Philadelphia in January 1792 to report on what had happened. Blaming the quartermaster, Samuel Hodgdon, as well as the War Department, the general asked for a court-martial in order to gain exoneration and planned to resign his commission after winning it. Washington, however, denied him the court-martial and forced St. Clair's immediate resignation.

The House of Representatives began its own investigation into the disaster. It was the first Congressional Special Committee investigation[15] as well as the first investigation of the executive branch. As part of the proceedings, the House committee in charge of the investigation sought certain documents from the War Department. Knox brought that matter to Washington's attention and because of the major issues of separation of powers involved, the president summoned a meeting of all of his department heads. It was one of the first meetings of all of the officials together and may be considered the beginning of the United States Cabinet.[36] Washington established, in principle, the position that the executive branch should refuse to divulge any papers or materials that the public good required it to keep secret and that at any rate, it was not to provide any originals. That is the earliest appearance of the doctrine of executive privilege,[37] which later became a major separation of powers issue.

The final committee report sided largely with St. Clair by finding that Knox, Quartermaster General Samuel Hodgdon, and other War Department officials had done a poor job of raising, equipping, and supplying St. Clair's expedition.[38] However, Congress voted against a motion to consider the Committee's findings and issued no final report. St. Clair expressed disappointment that his reputation was not officially cleared.[39]

Within weeks of learning of the disaster, Washington wrote, "We are involved in actual war!"[40] Following up on his 1783 "Sentiments on a Peace Establishment,"[41], he urged Congress to raise an army capable of conducting a successful offense against the American Indian confederacy, which it did in March 1792 by establishing additional army regiments (the Legion of the United States), adding three-year enlistments, and increasing military pay.[42] [34] That May, it also passed two Militia Acts. The first empowered the president to call out the militias of the several states. The second required free able-bodied white male citizens of the various states between the ages of 18 and 45 to enroll in the militia of the state in which they resided. Washington would use the authority to call out the militia in 1794 to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania.[43]

In late 1793, Major General "Mad Anthony" Wayne led 300 men from the Legion to the site of St. Clair's defeat. On 25 December, they identified the site because of the large amount of unburied remains. Private George Will wrote that to setup camp, the unit had to move bones to make space for their beds.[44] The Legion buried remains in a mass grave,[42] and quickly built Fort Recovery and spent the following months reinforcing the structure and searching for the abandoned artillery from St. Clair's defeat. On 30 June to 1 July 1794, the Legion successfully defended the fort from a Native American attack. The next month, the Legion won a decisive victory in the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The following year, the United States and the Native confederacy negotiated the Treaty of Greenville, which used Fort Recovery as a reference point for the boundary between American and Native settlements.[45] The treaty is considered to be the conclusion to the Northwest Indian War.

Legacy[]

The number of U.S. soldiers killed in St. Clair's defeat was more than three times the number the Sioux would kill 85 years later at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Despite being one of the worst disasters in U.S. Army history, the loss by St. Clair is largely forgotten.[3] The site of the battle is currently the town of Fort Recovery, Ohio, and includes a cemetery, memorial, and museum.[46]

One of the more significant effects of the Native American victory was the expansion in the United States of a standing, professional Army, as well as militia reforms.[3] The Congressional investigation into the battle also led to the establishment of executive privilege.[37]

Popular Culture[]

A story was published years after the defeat of St Clair about a skeleton of a Captain Roger Vanderberg and his diary that were supposedly found inside a tree in Miami County, Ohio. However, no one of that name was a casualty of the 1791 battle. The story originated in 1864 and was actually taken from a Scottish novel.[47]

A folk ballad, "St. Clair's Defeat" (or "Sinclair's Defeat"), was published in the 19th century;[48] Anne Grimes' quotes[49] Recollections of Persons and Places in the West by Henry M. Brackenridge, 1834, in which Brackenridge recalled hearing the song from its author, a blind poet named Dennis Loughey, at a racetrack in Pittsburgh around 1800.[50] It was collected as a folksong in Mary O. Eddy's 1939 book Ballads and Songs from Ohio.[51] It was recorded by Anne Grimes on her 1957 album, Ohio State Ballads[52] and by Bob Gibson and Hamilton Camp on their 1960 album Gibson & Camp at the Gate of Horn. It was also recorded as "St. Claire's Defeat" by the folk revival group the Modern Folk Quartet in 1964[53] and by Apollo's Fire in 2004.[54]

St. Clair's defeat is, along with the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, a likely source for the name of the fife and drum duet "Hell on the Wabash."[55]

See also[]

- List of battles won by Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Battle of Adwa

- Battle of Isandlwana

- Battle of the Little Bighorn

- Battle of Tippecanoe

References[]

- ^ Cornelius, Jim (4 November 2012). "The Battle of a Thousand Slain". FrontierPartisans.com. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Landon Y. Jones (2005). William Clark and the Shaping of the West. p. 41. ISBN 9781429945363.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Calloway, Colin G. (9 June 2015). "The Biggest Forgotten American Indian Victory". What It Means to be American. The Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Waxman, Matthew (4 November 2018). "Remembering St. Clair's Defeat". Lawfare.

- ^ Calloway 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Calloway 2015, p. 55.

- ^ Calloway 2018, p. 384.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fleming, Thomas (August 2009). "Fallen Timbers, Broken Alliance". Military History. History Reference Center, EBSCOhost. 26 (3): 36–43.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Winkler, 18-21

- ^ Jump up to: a b Calloway, C. 2015, p. 108.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Calloway 2018, p. 459.

- ^ Calloway, C. 2015, p. 157.

- ^ Carter, Life and Times, 62–3.

- ^ Allison 1986, p. 81.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Buffenbarger, Thomas E. (15 September 2011). "St. Clair's Campaign of 1791: A Defeat in the Wilderness That Helped Forge Today's U.S. Army". U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allison 1986, p. 82.

- ^ Shepherd, Joshua (Spring 2008). "Slaughter on the Wabash". HistoryNet.com. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 47.

- ^ Applied Anthropology Laboratories, Ball State University; Fort Recovery Historical Society. "Battle of the Wabash and Battle of Fort Recovery Walking Tour". Fort Recovery Historical Society. Note #6, "American Indian Alliance Strategy". Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Allison 1986, p. 83.

- ^ Griesmer, Daniel R. (December 2015). "1". The Evolution of Military Strategy and Ohio Indian Removal in the 1790s (Thesis). University of Akron. p. 2. 10024044. Retrieved 9 July 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Allison 1986, p. 84.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allison 1986, p. 85.

- ^ Hogeland 2017, p. 374.

- ^ Casualty statistics from "That Dark and Bloody River", by Allan W. Eckert, Bantam Books, December 1995.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sword, 196

- ^ Calloway 2018, p. 396.

- ^ Dwight L. Smith, "A North American Neutral Indian Zone: Persistence of a British Idea." Northwest Ohio Quarterly 61#2-4 (1989): 46-63

- ^ Sword 1985, p. 193.

- ^ Sword 1985, p. 194.

- ^ Sword 1985, p. 199.

- ^ Gaff, 11

- ^ Jump up to: a b Calloway, C. 2015, pp. 129-130.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schecter, 238

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hogeland 2017, p. 151.

- ^ Jenkins, Tamahome (18 November 2009). "St. Clair's Defeat and the Birth of Executive Privilege". Babeled.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosenberg, Morton (2008). "Presidential Claims of Executive Privilege: History, Law, Practice and Recent Developments" (PDF) (RL30319). Congressional Research Service: 1. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Feng, Patrick. "The Battle of the Wabash: The Forgotten Disaster of the Indian Wars". armyhistory.org. National Museum of the United States Army. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "Samuel Hodgdon, 5th Quartermaster General". Fort Lee, Virginia: US Army Quartermaster Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ Sword 1985, pp. 203-205.

- ^ Washington, George (1 May 1783). "Washington's Sentiments on a Peace Establishment, 1 May 1783". Founders Online. National Archives. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Corps of Discovery. United States Army". U.S. Army Center of Military History. 31 January 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "May 08, 1792: Militia Act establishes conscription under federal law". This Day In History. New York: A&E Networks. 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ Winkler, John F (2013). Fallen Timbers 1794: The US Army's first victory. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-7809-6377-8.

- ^ "Treaty of Greene Ville". Touring Ohio. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Applied Anthropology Laboratories, Ball State University; Fort Recovery Historical Society. "Battle of the Wabash and Battle of Fort Recovery Walking Tour". Fort Recovery Historical Society. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "Proposed Work at Fort Recovery May Solve Some of its Mysteries see letter in Comments by James L Murphy dated 7 January 2010 citing the story "Lost Sir Massingberd"". Ohio Historical Society Archaeology Blog. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Sara L. "Sinclair's (St. Clair's) Defeat - The Battle of Pea Ridge". The Kitchen Musician. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ Grimes, Anne (1957). Liner Notes, Ohio State Ballads (PDF). Smithsonian Folkways. p. 6. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ Brackenridge, Henry M. (1834). Recollections of persons and places in the West (1st ed.). Philadelphia: James Kay Jun. and Brother. p. 73. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ Eddy, Mary O. (1939). Ballads and songs from Ohio. New York: J.J. Augustin.

- ^ Grimes, Anne (1957). "St. Clair's Defeat - Ohio State Ballads". Smithsonian Folkways. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ Changes (LP). Modern Folk Quartet. Warner Bros. 1964. WS 1546.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ Scarborough Fayre: Traditional Tunes from the British Isles and the New World (Media notes). Apollo's Fire. 2010. KOCH KIC-CD-7577. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ Damm, Robert J (March 2011). "Rudamental Classics 'Hell on the Wabash'" (PDF). Percussive Notes: 29. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

Sources[]

- Allison, Harold (1986). The Tragic Saga of the Indiana Indians. Paducah: Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 0-938021-07-9.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis (1987). The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01318-2.

- Calloway, Colin Gordon (2015). The Victory with No Name: the Native American Defeat of the First American Army. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01993-8799-1.

- Calloway, Colin Gordon (2018). The Indian World of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190652166. LCCN 2017028686.

- Eid, Leroy V. (1993). "American Indian Military Leadership: St. Clair's 1791 Defeat". Journal of Military History. 57 (1): 71–88. doi:10.2307/2944223. JSTOR 2944223.

- Gaff, Alan D. (2004). Bayonets in the Wilderness. Anthony Wayne's Legion in the Old Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3585-9.

- Guthman, William H. (1970). March to Massacre: A History of the First Seven Years of the United States Army. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-025297-1.

- Hogeland, William (2017). Autumn of the Black Snake. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374107345. LCCN 2016052193.

- Odo, William O. (1993). "Destined for Defeat: an Analysis of the St. Clair Expedition of 1791". 'Northwest Ohio Quarterly. 65 (2): 68–93.

- Schecter, Barnet (2010). George Washington's America. A Biography Through His Maps. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1748-1.

- Sugden, John (2000). Blue Jacket: Warrior of the Shawnees. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4288-3.

- Sword, Wiley (1985). President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1864-4.

- Van Trees, Robert V. (1986). Banks of the Wabash. Fairborn, Ohio: Van Trees Associates. ISBN 0-9616282-3-5.

- Winkler, John F. (2011). Wabash 1791: St. Clair's Defeat; Osprey Campaign Series #240. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-676-9.

External links[]

- 1791 in the United States

- Conflicts in 1791

- Battles in Ohio

- Battles involving Native Americans

- Battles of the Northwest Indian War

- Pre-statehood history of Ohio

- Mercer County, Ohio