John Henry Foley

John Henry Foley | |

|---|---|

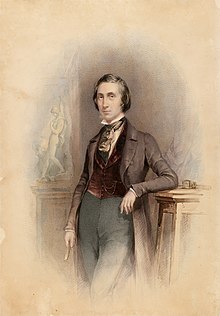

John Henry Foley in 1863, by Ernest Edwards | |

| Born | 24 May 1818 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 27 August 1874 (aged 56) Hampstead, London |

| Resting place | St. Paul's Cathedral, London |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Alma mater | Royal Academy Schools |

| Known for | Sculpture |

John Henry Foley RA (24 May 1818 – 27 August 1874), often referred to as J. H. Foley, was an Irish sculptor, working in London. he is best known for his statues of Daniel O'Connell in Dublin,[1] and of Prince Albert for the Albert Memorial in London.[2]

Life[]

Foley was born 24 May 1818, at 6 Montgomery Street, Dublin, in what was then the city's artists' quarter. The street has since been renamed Foley Street in his honour.[3] His father was a glass-blower and his step-grandfather Benjamin Schrowder was a sculptor.[4] At the age of thirteen he began to study drawing and modelling at the Royal Dublin Society, where he took several first-class prizes.[2] In 1835 he was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools in London.[2] He exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time in 1839,[2] and came to fame in 1844 with his Youth at a Stream. Thereafter commissions provided a steady career for the rest of his life. In 1849 he was made an associate, and in 1858 a full member of the Royal Academy of Art.[2]

When, in 1851, inspired by the recently closed Great Exhibition, the Corporation of London voted a sum of £10,000 to be spent on sculpture to decorate the Egyptian Hall in the Mansion House, Foley was commissioned to make sculptures of Caractacus and Egeria.[5]

In 1864 he was chosen to sculpt one of the four large stone groups, each representing a continent, at the corners of George Gilbert Scott's Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens. His design for Asia was approved in December of that year. In 1868, Foley was also asked to make the bronze statue of Prince Albert himself, to be placed at the centre of the memorial, following the death of Carlo Marochetti, who had originally received the commission, but had struggled to produce an acceptable version.[6]

Foley exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1839 and 1861. Further works were shown posthumously in 1875. His address is given in the catalogues as 57, George St., Euston Square, London until 1845, and 19, Osnaburgh Street from 1847.[7]

Foley died at Hampstead, north London on 27 August 1874, and was buried in the crypt[8] at St. Paul's Cathedral on 4 September.[2] He left his models to the Royal Dublin Society, where he had his early artistic education, and a large part of his property to the Artists' Benevolent Fund.[2] He did not see the Albert Memorial completed before his death. A statue of Foley himself, on the front of the Victoria and Albert Museum, depicts him as a rather gaunt figure with a moustache, wearing a floppy cap.

Pupils[]

Foley's pupil Thomas Brock brought several of Foley's works to completion after his death, including his statue of Prince Albert for the Albert Memorial. Foley's articled pupil and later studio assistant Francis John Williamson became a successful sculptor in his own right, reputed to have been Queen Victoria's favourite.[9] Other pupils and assistants were Charles Bell Birch, Samuel Ferris Lynn, Charles Lawes, and Richard Belt.

Destruction of works in Ireland[]

Following the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, a number of Foley's works were removed, or destroyed without notice, because the persons portrayed were considered hostile to the process of Irish independence. They included those of Lord Carlisle, Lord Dunkellin (in Galway) and Field Marshal Gough in the Phoenix Park.[10] The statue of Lord Dunkellin was decapitated and dumped in the river as one of the first acts of the short-lived "Galway Soviet" of 1922.[11]

Gallery[]

Daniel O'Connell O'Connell Street, Dublin

Michael Faraday in London

Prince Albert in the Albert Memorial, Hyde Park

Stonewall Jackson in Richmond, Virginia. Removed July 1, 2020.

Statue of Father Mathew in St. Patrick's Street, Cork

Statue of Benjamin Guinness in the grounds of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin

Statue of Hermaphroditus at Bancroft Gardens, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire

The statue of Lord Carlisle, which stood in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, from 1870–1956

Statue of Sir James Outram at Maidan, now in garden of Victoria Memorial, Kolkata, India

Statue of Dominic Corrigan, Graves Hall, the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland

Statue of Sir Henry Marsh, Graves Hall, the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland

Statue of Robert James Graves, Graves Hall, the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland

Statue of William Stokes, Graves Hall, the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland

John Sheepshanks by John Henry Foley, 1866, Victoria & Albert Museum

Works[]

Notable works by Foley include:[12]

In London:

- Egeria (1856) and Caractacus (1857), for the Mansion House, London.

- The Elder Brother from Comus (1860), his Royal Academy diploma work.

- The Muse of Painting (1866), a monument to James Ward, R.A. at Kensal Green Cemetery.[12]

- John Hampden (1847), John Selden (1853) and Charles Barry (1866), for the Palace of Westminster.[12]

- Sir Joshua Reynolds, in marble, Tate Gallery collection.[13]

- The symbolical group representing Asia, and the statue of the prince himself, for the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens.

- Michael Faraday, in marble, for the Royal Institution. The finished statue was made by Thomas Brock after Foley's death and installed in 1876.[14]

In Ireland:

- Oliver Goldsmith (commissioned 1861; erected 1864) and Edmund Burke (1868), outside Trinity College, Dublin.

- Daniel O'Connell (1866–74), O'Connell Street, Dublin.

- Sir BL Guinness (1875), Dublin.

- Field Marshal Gough, formerly in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, now at Chillingham Castle.

- Henry Grattan, College Green, Dublin. Model shown in Dublin in 1872; statue inaugurated January 1876.

- Sir Dominic Corrigan (1869), in marble, at the Graves Hall at the Royal College of Surgeons, Dublin.[15]

- Ulick de Burgh, Lord Dunkellin (1873), Eyre Square, Galway

- Memorial to Brigadier General John Nicholson (1862), Lisburn Cathedral.[16]

- Memorial to Father Mathew, campaigner for teetotalism (1864), Cork.

Elsewhere:

- Statue in memory of George Howard, the 7th Earl of Carlisle. Brampton Cumbria 1869 (another version in Dublin was blown up by IRA 1956)

- Hermaphroditus or Youth at the stream (1844), cast in bronze by J. Hadfield for The Great Exhibition of 1851. Now at Bancroft Gardens in Stratford-upon-Avon. According to a plaque which accompanies it, the statue was donated to the gardens by in 1932.[17]

- Lord Clyde (1868), Glasgow.

- Clive, Shrewsbury.

- Viscount Hardinge an equestrian statue, completed in 1857 for Calcutta.[12] Removed from its original site in 1950[18] it was returned to England and set up on a Hardinge family property at Penshurst, Kent. It was later relocated to the garden of a house in Over, Cambridgeshire.[19][20]

- Canning (1874) for Calcutta. An equestrian statue, completed posthumously from Foley's small model,[12] was moved to Barrackpore in 1969.[18]

- Sir James Outram (1864), for Calcutta. Originally at the Maidan, now in the garden of the Victoria Memorial.[18]

- Memorial to the lawyer James Stuart (1854) for Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

- Stonewall Jackson, Richmond, Virginia.

Noteworthy[]

The Hereford Times makes special mention of John Henry Foley on 24 May 1873 in the published memoriam of Victorian era artist, Charles Lucy: "Mr. Foley, the eminent sculptor, has taken a cast of the head and face of the deceased, whose fine expressive features are described as singularly beautiful in death."[21] However, whether Mr. Foley made a sculpture from this cast remains to be seen.

See also[]

- List of public art in the City of London

- List of public art in Dublin

- List of public art in Cork

References[]

- ^ Potterton, Homan (1973). The O'Connell Monument. Dublin.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 599.

- ^ Behan, A. P. (Spring 2001). "Bye Bye Century!". Dublin Historical Record. Old Dublin Society. 54 (1): 82–100. JSTOR 30101842.

- ^ Turpin, John T. (March 1979). "The Career and Achievement of John Henry Foley, Sculptor (1818-1874)". Dublin Historical Record. 32 (2): 42–53. JSTOR 30104301.

- ^ Catalogue of the Sculpture, Paintings, Engravings, and Other Works of Art belonging to the Corporation, together with the Books not included in the Catalogue of the Guildhall Library. Part the First. Printed for the use of the members of the Corporation of London. 1867. pp. 43–7.

- ^ F. H. W. Sheppard (GeneralEditor) (1975). "Albert Memorial: The memorial". Survey of London: volume 38: South Kensington Museums Area. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Graves, Algernon (1905). The Royal Academy: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors from its Foundations in 1769 to 1904. 3. London: Henry Graves. pp. 130–2.

- ^ "Memorials of St Paul's Cathedral" Sinclair, W. p. 469: London; Chapman & Hall, Ltd; 1909.

- ^ "Francis John Williamson (1833-1920)". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Notes on destruction and removal, accessed 20 January 2009

- ^ Citation, accessed 6 July 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Turpin, John T. (1979). "Catalogue of the Sculpture of J.H. Foley". Dublin Historical Record. 32: 108–18.

- ^ "Foley: Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ James, Frank AJL, ed. (2017). 'The Common Purposes of Life': Science and Society at the Royal Institution of Great Britain. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 73. ISBN 978-1351963176.

- ^ Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin : the city within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 483. ISBN 9780300109238.

- ^ Potterton, Homan (1975). Irish Church Monuments, 1570-1880. Belfast.

- ^ Waymark UK Image Gallery An explanatory plaque is also accessiblehere.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Information on Sculptures". Victoria Memorial Hall. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Sworder, John. "St Peter's Church". Fordcombe Village. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1331332)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Charles Lucy - historical painter - Hereford Times". www.harmonics.com. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

External links[]

Media related to John Henry Foley at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John Henry Foley at Wikimedia Commons- 30 artworks by or after John Henry Foley at the Art UK site

- Details of recent book and documentary film on Foley.

- 1818 births

- 1874 deaths

- 19th-century Irish sculptors

- Artists from Dublin (city)

- Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

- Royal Academicians

- Alumni of the Royal Academy Schools