Kadavil Chandy

Kadavil Chandy | |

|---|---|

| Archdeacon of All India of the Archdiocese of Cranganore | |

| Appointed | by Parambil Chandy |

| Predecessor | Arkadeacon Parambil Thoma |

| Successor | Givargis of Saint John |

Kadavil Chandy Kathanar (c. 1588-1673), also known as Alexander the Indian (Syriac: ܐܲܠܟܣܲܢܕܪܘܿܣ ܗ̤ܢܕܘܿܝܐ, romanized: Alaksandros hendwāyā) was a Kathanar (priest) and a celebrated scholar, orator, hymnographer and syriacist from the Saint Thomas Christian community in India.[1][2] He was a prominent face of the Saint Thomas Christians and lead their Catholic faction during a turbulent period of divisions in the community after the Coonan Cross Oath of 1653. He was from Kaduthuruthy, Kottayam in Kerala state of India. He often reacted vehemently against the colonial Padroado latin subjugation over his community and resisted their ecclesiastical and cultural dominance. He was widely reputed for his knowledge in Syriac language and literature, and was often praised, both among his own community and the European missionaries who wrote about him in their letters addressed to the Portuguese monarch and to the Pope. His acrostic poems propagated even among West Asia's Syriac-speaking communities.[3] Although he stood against the latin colonialists, he commanded respect from the Portuguese and the local Hindu kings alike.[1]

Name[]

His name, Chandy (Chāṇṭi), is a Malayalam adaptation of the short form for 'Alexander'.[1] The Portuguese missionaries often used the nickname Alexander the Indian. This nickname is noted in Mannanam Syr 63, a 336-page eighteenth century manuscript that is currently archived in Saint Joseph’s Monastery of the Carmelites of Mary Immaculate (CMI), at Mannanam, Kerala.[4] The Syriac term for India is Hendo. Similarly, the term that denotes Indian (or pertaining to India) in Syriac literature is hendwāya. Meanwhile, the copyist has also used the Syriac equivalent of Chandy's house name, l'mēnāyā (lit."connected to the port", or “near the jetty”), for Kadavil.[1]

Biography[]

Chandy was born in 1588 into the Kadavil family of Kaduthuruthy.[5] Many of the members of his family were priests. His friendly relations with the Rajah of Purakkatt shows that he must be of aristocratic origins.[5] He was enrolled into deaconate in the Vaippikotta Seminary.[5] There he received his clerical training and he mastered the basics of humanist training and theology. His further studies was under Fransisco Ros (during c. 1601-1624), the Padroado Archbishop of Cranganore-Angamaly, who was a linguistic genius, an excellent Syriacist and fluent in Malayalam.[5]

However, he had a troublesome relationship with Stephen Britto (during c. 1624-1641), the successor of Fransisco Ros.[5] Brito often employed incompetent European teachers to teach Syriac at the Vaippikotta Seminary.[5] Britto even excommunicated Chandy for several years. The relationship between the Saint Thomas Christians and Jesuits reached its breaking point after 1641 during the archiepiscopate of Francis Garcia Mendes (d. c. 1659). Parambil Thoma, the archdeacon of the community, was often in conflict with Garcia. Beginning in 1645, the continuous conflict started escalating, with Chandy taking the side of the Archdeacon. Therefore, the Saint Thomas Christian priests wrote a petition and presented it to the Portuguese viceroy Dom Philip Mascarenhas in 1645, complaining about the abuses that face from their ecclesiastical administrators. The petition also mentions Kadavil Chandy as the most capable candidate for teaching Syriac in the Seminary.[5] The petition thus explains the reason behind the hostility between Chandy and Britto.[5]

István Perczel, a leading expert on the Saint Thomas Christians,[6] observes as follows:[5]

"The stories of the short-lived Congregation of Saint Thomas and of this petition shed an interesting light on the combination of Latinisation and racism that triggered conflicts between the Europeans and a highly learned local elite, who were revolting not against the Catholic faith itself but rather against these twin social tendencies. "

In 1652, Chandy warned the archbishop of the impending schism.[5] However, Garcia was adamant in his attitude towards them. On c. 1653 January 3, the Saint Thomas Christians held a protest against the ecclesiastical subjugation from Garcia and the Portuguese Padroado Jesuits that came to be known as the Coonan Cross Oath.[5] After the Coonan Cross oath, he was selected to be one of the four consulters and councilors of Archdeacon Thoma.[5] Chandy was instrumental in persuading Saint Thomas Christians to safeguard their liturgical patrimony against the liturgical latinisations and political dominance of the Portuguese.[5]

The Coonan Cross revolt is explained by Stephen Neill as follows:[7]

"In January 1653 priests and people assembled in the church of Our Lady at Mattanceri, and standing in front of a cross and lighted candles swore upon the holy Gospel that they would no longer obey Garcia, and that they would have nothing further to do with the jesuits they would recognise the archdeacon as the governor of their church. This is the famous oath of the 'Koonen Cross' (the open-air Cross which stands outside the church at Mattanchery)... The Thomas Christians did not at any point suggest that they wished to separate themselves from the pope. They could no longer tolerate the arrogance of Garcia. And their detestation of the jesuits, to whose overbearing attitude and lack of sympathy they attributed all their troubles,breathes through all the documents of the time. But let the pope send them a true bishop not a jesuit, and they will be pleased to receive and obey him."

A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707 By Stephen Neill page 326-327

However, following the Coonan Cross Oath, rumours and forgeries started spreading among the Saint Thomas Christians. Most extant of these were the letters forged in the name of Ahatallah.[8] Anjilimoottil Itty Thomman, an old Knanaya priest and the vicar of the Kallissery Knanaya Church, is said to be the mastermind behind the forged letters.[8] These letters were addressed to the Saint Thomas Christians urging them to consecrate their archdeacon to episcopal dignity by the laying of hands of twelve priests. Being a staunch supporter of Parambil Thoma, Itty Thomman wanted to see the archdeacon raised to episcopacy at any cost.[8] Being a good Syriac scholar for himself, Itty Thomman could easily forge letters in Syriac language.[8] But most of the other Saint Thomas Christian leaders, including Parambil Chandy and Vengoor Givargis, did not doubt the authenticity of the letter and hence they stood with Archdeacon Thoma and Itty Thomman, who were moving ahead with the implementation of the instructions mentioned in the letters.[8] Thus, Thoma was proclaimed bishop at Alangad by twelve priests, lead by Itty Thomman.[8] Soon, the Pope sent Propaganda fide led by an Italian Carmelite missionary, Joseph Maria Sebastiani, in an objective to reconcile the revolted Saint Thomas Christians with the Catholic Church.[9] Sebastiani could easily covince Kadavil Chandy Kathanar and gather the support of many Syrian Christians. At the same time, Kadavil Chandy also ensured that the Saint Thomas Christians would be independent from the Portuguese Padroado. He tried to convince Sebastiani to consecrate Archdeacon Thoma. But Sebastiani rejected this demand raising the indiscipline and disobedience of the archdeacon. When Parampil Chandy Kathanaar and Vengoor Giwargis Kathanaar reconciled with him, Sebastiani was finally ready to consecrate an indigenous bishop for the Saint Thomas Christians. However, Sebastiani did not recognise Archdeacon Thoma but Parambil Chandy as the eligible candidate.[10] Parambil Chandy would be elevated as Catholic hierarch of the St. Thomas Christians at Kaduthuruthy Knanaya Valiypally on February 1, 1663.[11]

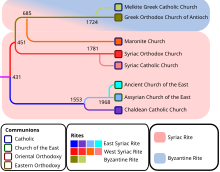

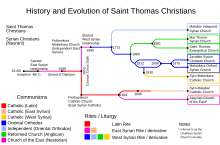

Archdeacon Thoma, meanwhile sent requests to the Jacobite Church of Antioch to receive canonical consecration as bishop.[12] In 1665, Abdul Jaleel, a bishop sent by the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch Ignatius ʿAbdulmasīḥ I, arrived in India and he consecrated Thoma canonically as a bishop.[13] The visits of prelates from the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch to the faction that was led by Thoma continued since then and this led to gradual replacement of the East Syriac Rite liturgy with the West Syriac Rite and the faction affiliated to the Miaphysite Christology of the Oriental Orthodox Communion.[12] The Syrian Catholics continued with their original East Syriac Rite traditions.[12] Between 1661 and 1665, Parambil Chandy gained the support of 84 of the 116 churches, while Archdeacon Thoma was supported by the remaining 32.[14]

This led to the first lasting formal schism in the Saint Thomas Christian community. Thereafter, the faction affiliated with the Catholic Church under Parambil Chandy was designated the Pazhayakuttukar, or "Old Allegiance", while the branch affiliated with Thoma was called the Puthankuttukar, or "New Allegiance".[15]

Kadavil Chandy, at the age of seventy-five became the Vicar General of Parambil Chandy, the bishop of the Catholic Saint Thomas Christians.[5] He remained in the position until 1673 when he was succeeded by George of Saint John. It is safe to assume that he died at or shortly after 1673.[5]

Works[]

The memra on the Holy Qurbana[]

One of the surviving poems composed by Chandy is preserved in the aforementioned manuscript, Mannanam Syr 63, of the Monastery at Mannanam. This manuscript has an acrostic poem by Chandy in its folios 146r to 157v.[1][16] The manuscript was copied (copying was completed on February 9, 1734) by Pilippose bar Thomas Kraw Yambistha (Syriac, for “on dry land”, Malayalam Karayil) and completed on February 9 1734. The copyist was part of the parish of Marth Mariam Church at Kallūṛkkāṭû (Kalloorkkad, present day Champakkulam), Alappuzha, Kerala.[1] This manuscript has the East Syriac propria of prayers for Canonical hours and it starts those for the Sundays of the East Syriac liturgical season of Śūbārā. The poem’s title, possibly given by the copyist, reads: Mēmra dawīd l'qaśīśā aleksandrōs hendwāyā deskannī l'mēnāyā d'al qurbān m'śīhā, nemmar b'qal sāgdīnan (Syriac, lit."Poetic homily by Father Priest Elder Alexander the Indian, who is called ‘At the Port’ (Kadavil), about the sacrifice of Christ (Holy Qurbana), in the tune of Sāgdīnan”).[1] The title of the poem also makes it evident that the poem is composed in the meter and melody of 'Sāgdīnan', a popular Syriac hymn of the Saint Thomas Christians. 'Sāgdīnan' is the last stanza of Bṛīk Hannāna, the East Syriac christological hymn composed by Babai the Great.[16]

Joseph J. Palackal, an Indic musicologist who has studied the poem, explains its rhyming scheme as follows:[1]

"There are 22 strophes, one for each letter in the Syriac alphabet. There are twelve syllables in each verse, with rhyme on the ultimate syllable. The rhyming syllable is rēś, the twentieth letter in the alphabet. The first strophe begins in the middle of the seventh line on folio 146, on ālap, the first letter of the Syriac alphabet".

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Joseph J. Palackal.

- ^ István Perczel (2014), p. 30-49.

- ^ P. J. Thomas (1989).

- ^ Emmanuel Thelly (2004).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o István Perczel (2014), p. 31.

- ^ "Perczel's profile at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum".

- ^ Neill 2004, p. 326-327.

- ^ a b c d e f Neill 2004, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Mundadan, Anthony Mathias; Thekkedath, Joseph (1982). History of Christianity in India. Vol. 2. Bangalore: Church History Association of India. pp. 96–100.

- ^ Vellian 1986, p. 31-36.

- ^ Vellian 1986, p. 35-36.

- ^ a b c Brock (2011).

- ^ Joseph, Thomas (2011). "Malankara Syriac Orthodox Church". In Sebastian P. Brock; Aaron M. Butts; George A. Kiraz; Lucas Van Rompay (eds.). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Gorgias Press. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Medlycott, A (1912). "St. Thomas Christians". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Vadakkekara, Benedict (2007). Origin of Christianity in India: A Historiographical Critique. Delhi: Media House. p. 84. ISBN 9788174952585.

- ^ a b István Perczel (2014), p. 32.

Further reading[]

- Alexander Toepel (2011). Timothy B Sailors; Alexander Toepel; Emmanouela Grypeou; Dmitrij Bumazhnov (eds.). "A letter from Alexander Kadavil to the Congregation of St. Thomas at Edapally". Bibel, Byzanz und Christlicher Orient: Festschrift für Stephen Gerö zum 65. Geburtstag (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 187; Leuven: Peeters). Gorgias Press. Uitgeverij Peeters en Departement Oosterse Studies. ISBN 9789042921771. ISSN 0777-978X.

- István Perczel (2014). Amir Harrak (ed.). "A Syriacist Disciple of the Jesuits in 17th-Century India: Alexander of the Port/Kadavil Chandy Kathanar". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. Gorgias Press. 14. ISBN 9781463236618. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Sources[]

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2011). "Thomas Christians". In Sebastian P. Brock; Aaron M. Butts; George A. Kiraz; Lucas Van Rompay (eds.). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Gorgias Press. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- P. J. Thomas (1989). Malayāḷasāhityawum kṛistyānikaḷum Malayalam Literature and Christians 3rd ed. with an appendix by Scaria Zacharia. Kottayam: D. C. Books. p. 36, 143, 149.

- Joseph J. Palackal. "SYRO MALABAR CHURCH JESUS & INDIA A CONNECTION THROUGH ARAMAIC LANGUAGE AND MUSIC".

- Emmanuel Thelly (2004). "Syriac manuscripts in Mannanam Library". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 56: 257-270. doi:10.2143/JECS.56.1.578706.

- Vellian, Jacob (1986). Symposium on Knanites. Syrian Church Series. Vol. 12. Jyothi Book House.

- Neill, Stephen (2004) [1984]. A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521548854.

- 1588 births

- Syriac writers

- 1673 deaths

- Saint Thomas Christians

- Syro-Malabar Catholic Church

- Syro-Malabar Catholics

- 17th-century Indian scholars

- Christian clergy from Kerala