Church of the East in China

The Church of the East or the sometimes referred to as Nestorian Church historically had a presence in China during two periods: first from the 7th through the 10th century, and later during the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in the 13th and 14th centuries. Locally, the religion was known as Jingjiao (Chinese: 景教; pinyin: Jǐngjiào; Wade–Giles: Ching3-chiao4; lit. 'Luminous Religion').

After centuries of latency, the 21st century marked a historical moment between the Assyrian Church of the East and the Church in China, when the Liturgy of Addai and Mari was celebrated.[1]

Tang era[]

History[]

Two possibly Nestorian (Church of the East) monks were preaching Christianity in India in the 6th century before they smuggled silkworm eggs from China to the Eastern Roman Empire.

The first recorded Christian mission to China was led by the Syriac monk known in Chinese as Alopen. Alopen's mission arrived in the Chinese capital Chang'an in 635, during the reign of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty. Taizong extended official tolerance to the mission and invited the Christians to translate their sacred works for the imperial library. This tolerance was followed by many of Taizong's successors, allowing the Church of the East to thrive in China for over 200 years.[2][3]

China became a metropolitan province of the Church of the East, under the name Beth Sinaye, in the first quarter of the 8th century. According to the 14th-century writer ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis, the province was established by the patriarch Sliba-zkha (714–28).[4] Arguing from its position in the list of exterior provinces, which implied an 8th-century foundation, and on grounds of general historical probability, ʿAbdishoʿ refuted alternative claims that the province of Beth Sinaye had been founded either by the 5th-century patriarch Ahha (410–14) or the 6th-century patriarch Shila (503–23).[5]

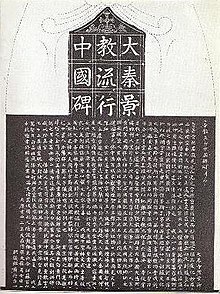

In 781 the Christian community in Chang'an erected a tablet known as the Nestorian Stele on the grounds of a local monastery. The stele contains a long inscription in Chinese with Syriac glosses, composed by the cleric Adam, probably the metropolitan of Beth Sinaye. The inscription describes the eventful progress of the Nestorian (Church of the East) mission in China since Alopen's arrival. The inscription also mentions the archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan [Chang'an] and Gabriel of Sarag [Lo-yang]; Yazdbuzid, 'priest and country-bishop of Khumdan'; Sargis, 'priest and country-bishop'; and the bishop Yohannan. These references confirm that the Church of the East in China had a well-developed hierarchy at the end of the 8th century, with bishops in both northern capitals, and there were probably other dioceses besides Chang'an and Lo-yang.

It is unlikely that there were many Christian communities in central China, and the only inland Chinese city south of the Yellow River where a Nestorian presence can be confirmed in the Tang dynasty is Chengdu.[6] And two monasteries have been located in Chengdu and Omei Shan, both in Sichuan.[7] Shortly afterwards Thomas of Marga mentions the monk David of Beth ʿAbe, who was metropolitan of Beth Sinaye during the reign of Timothy I (780–823). Timothy I is said also to have consecrated a metropolitan for Tibet (Beth Tuptaye), a province not again mentioned.

Decline[]

In 845, a decree issued by Emperor Wuzong demanded that foreign religions like Nestorianism be cast out of the kingdom. The decree required that Nestorians be forced to return to laity and become taxpayers.[8] The decree had tremendously negative effects on the Nestorian community and later imperial decrees calling for religious toleration probably had no effect for the Nestorians, who were likely severely marginalized or extinct by then.[8]

The province of Beth Sinaye is last mentioned in 987 by the Arab writer Ibn al-Nadim, who met a Nestorian monk who had recently returned from China, who informed him that 'Christianity was just extinct in China; the native Christians had perished in one way or another; the church which they had used had been destroyed; and there was only one Christian left in the land'.[9] The collapse of the Church of the East in China coincided with the fall of the Tang Dynasty, which led to a tumultuous era (the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period).[3]

The complete extinction of Nestorianism after the Tang dynasty can be traced to the fact that the religion was evidently foreign and dependent on imperial support. Majority of Nestorians in Tang China were foreigners from Persia or Central Asia. Considering the lack of native Chinese converts, the religion was a foreign faith practiced by foreigners. The most decisive factor to the collapse of Nestorianism was the church's strong reliance on Tang imperial protection and patronage. After the fall of the Tang dynasty, what was left of the Nestorian church quickly vanished without political support.[10]

Literature[]

Dozens of Jingjiao texts were translated from Syriac into Chinese. Only a few have survived. These are generally referred to as the Chinese Jingjiao Documents. One of the surviving texts, the Zunjing or Book of Praise (尊經), lists about 35 books that had been translated into Chinese. Among these books are some translations of the Scriptures, including the Pentateuch (牟世法王經) - Genesis is known as 渾元經, Psalms (多惠聖王經), the Gospels (阿思瞿利容經), Acts of the Apostles (傳化經) and a collection of the Pauline epistles (寳路法王經). These translations of the Scriptures have not survived. However, three non-scriptural Christian books listed in the Zunjing are among the Jingjiao manuscripts that were discovered in the early 20th century: the Sutra on the Origin of Origins, the Sutra of Ultimate and Mysterious Happiness, and the Hymn of Perfection of the Three Majesties (also called Gloria in Excelsis Deo). Two additional Jingjiao manuscripts not listed in the Zunjing have also been discovered: Sutra of Hearing the Messiah and Treatise on the One God.[11][12]

Mongol era[]

The Mongols called "Nestorian" Christians (or "Nestorian" Christian priests in particular) Arka′un or Erke′un,[13][self-published source] which was later applied for Christians in general (including Roman Catholics)[14][15] whereby Christianity was named in Chinese as 也里可溫教 (Yělǐkěwēn jiào). However, there is a suggestion that the term Yělǐkěwēn jiào might be used also for Míng jiào and some other religions in Jiangnan.[16]

History[]

The Church of the East had significant evangelical success under the Mongol Empire. The Mongol invasion of China in the 13th century allowed the church to return to China. By the end of the century two new metropolitan provinces had been created for China: Tangut and 'Katai and Ong'.[17]

The province of Tangut covered northwestern China, and its metropolitan seems to have sat at Almaliq. The province evidently had several dioceses, even though they cannot now be localised, as the metropolitan Shemʿon Bar Qaligh of Tangut was arrested by the patriarch Denha I shortly before his death in 1281 'together with a number of his bishops'.[18]

The province of Katai (Cathay) and Ong, which seems to have replaced the old Tang dynasty province of Beth Sinaye, covered northern China and the country of the Christian Ongut tribe around the great bend of the Yellow River. The metropolitans of Katai and Ong probably sat at the Mongol capital Khanbaliq. The patriarch Yahballaha III grew up in a monastery in northern China in the 1270s, and the metropolitans Giwargis and Nestoris are mentioned in his biography.[19] Yahballaha himself was consecrated metropolitan of Katai and Ong by the patriarch Denha I shortly before his death in 1281.[20]

During the first half of the 14th century there were Nestorian Christian communities in many cities in China, and the province of Katai and Ong probably had several suffragan dioceses. In 1253 William of Rubruck mentioned a Nestorian bishop in the town of 'Segin' (Xijing, modern Datong in Shanxi province). The tomb of a Nestorian bishop named Shlemun, who died in 1313, has recently been discovered at Quanzhou in Fujian province. Shlemun's epitaph described him as 'administrator of the Christians and Manicheans of Manzi (south China)'. Marco Polo had earlier reported the existence of a Manichean community in Fujian, at first thought to be Christian, and it is not surprising to find this small religious minority represented officially by a Christian bishop.[21]

The relationship between the Catholic Franciscan missionaries and the Nestorian Christians were strained and often in conflict. The Catholics viewed the Nestorians as heretics and rivals while the Nestorians viewed them as political rivals. Roman Catholicism in China was expanded at the expense of the Nestorians during the Yuan dynasty, with some Nestorians being converted to Catholicism.[22]

Decline[]

The Church of the East declined in China substantially in the mid-14th century. Several contemporaries, including the papal envoy John of Marignolli, mention the murder of the Latin bishop Richard and six of his companions in 1339 or 1340 by a Muslim mob in Almaliq, the chief city of Tangut, and the forcible conversion of the city's Christians to Islam.[23] The last tombstones in two East Syriac cemeteries discovered in Mongolia around the end of the 19th century date from 1342, and several commemorate deaths during a plague in 1338.[24] In China, the last references to East Syriac and Latin Christians date from the 1350s, and it is likely that all foreign Christians were expelled from China soon after the revolution of 1368, which replaced the Mongol Yuan dynasty with the xenophobic Ming dynasty.[25]

Additional reasons for the decline and disappearance of Nestorianism include the foreign character of the religion and its adherents, comprising a Central Asian and Turkic-speaking immigrant community. There was a lack of native Chinese converts, lack of any Chinese translations of the Bible, and a heavy political reliance on imperial Mongol patronage. In consequence of these factors, once the Yuan dynasty fell the Nestorians in China quickly became marginalized and soon vanished, leaving little trace of their existence.[26]

Modern Day (20th century-present)[]

In 1998, the Assyrian Church of the East sent then-Bishop Mar Gewargis to China.[27] A later visit to Hong Kong led the Assyrian Church to state that: "after 600 years The Eucharistic Liturgy, according to the anaphora of Mar Addai & Mari was celebrated at the Lutheran Theological Seminary chapel on Wednesday evening, October 6, 2010."[1] This visit was followed up two years later at the invitation of the Jǐngjiào Fellowship with Mar Awa Royel accompanied by Reverend and Deacon, arriving in Xi'an, China in October 2012. On Saturday October 27, the Holy Eucharist in the Aramaic language was celebrated by Mar Awa, assisted by Fr. Genard and Deacon Allen in one of the churches in the city.[28]

See also[]

- Nestorian Stele

- Daqin Pagoda

- Jingjiao Documents

- Rabban Bar Sauma

- Yahballaha III

- Ongud

- Keraites

- Painting of a Nestorian Christian figure

- Murals from the Nestorian temple at Qocho

References[]

- ^ a b "The Return to China". Assyrian Church News. 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Moule, Christians in China before the Year 1550, 38

- ^ a b Moffett, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Mai, Scriptorum Veterum Nova Collectio, x. 141

- ^ Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church, 123–4

- ^ Li, Tang; Winkler, Dietmar W., eds. (2016). Winds of Jingjiao. Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 261. ISBN 9783643907547.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (2016). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity (New ed.). London: I.B. Tauris. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-78453-683-1.

- ^ a b Moffett, Samuel Hugh (1998). A History of Christianity in Asia, Vol. I: Beginnings to 1500. Orbis Books. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-60833-162-8.

- ^ Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church, 222

- ^ Moffett, Samuel Hugh (1998). A History of Christianity in Asia, Vol. I: Beginnings to 1500. Orbis Books. pp. 312–313. ISBN 978-1-60833-162-8.

- ^ P. Y. Saeki, The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China, pp. 248-265

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Johnson, Dale A. (2013). Searching for Jesus on the Silk Road. p. 133. ISBN 978-1300435310.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization. City University of HK Press. 2007. p. 680. ISBN 978-9629371401.

- ^ Oort, J. van Johannes; Berg, Jacob Albert van den, eds. (2011). "A New Interpretation of Yelikewen and its relation to Mingjiao". In Search of Truth. Augustine, Manichaeism and Other Gnosticism. pp. 352–359?. ISBN 978-9004189973.

- ^ Fiey, POCN, 48–9, 103–4 and 137–8

- ^ Bar Hebraeus, Ecclesiastical Chronicle, ii. 450

- ^ Wallis Budge, The Monks of Kublai Khan, 127 and 132

- ^ Bar Hebraeus, Ecclesiastical Chronicle, ii. 452

- ^ Lieu, S., Manichaeism in Central Asia and China, 180

- ^ Tang, Li (2011). East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China. Harrassowitz. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1.

- ^ Yule and Cordier, Cathay and the Way Thither, iii. 31–3 and 212

- ^ Nau, ‘Les pierres tombales nestoriennes du musée Guimet’, ROC, 18 (1913), 3–35

- ^ Moule, Christians in China before the Year 1550, 216–40

- ^ Tang, Li (2011). East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China. Harrassowitz. pp. 146, 149. ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1.

- ^ "Biography of HH Mar Gewargis III". Assyrian Church News. 2015-09-28. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ "Bishop Mar Awa Royel Visits China". Assyrian Church News. 2012-12-10. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

Further reading[]

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1993). Pour un Oriens Christianus Novus: Répertoire des diocèses syriaques orientaux et occidentaux. Beirut: Orient-Institut. ISBN 9783515057189.

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. (1997). Manichaeism in Central Asia and China. Brill. ISBN 9004104054

- Moffett, Samuel Hugh (1999). "Alopen". Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780802846808.

- Malek, Roman; Peter Hofrichter, eds. (2006). Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Sankt Augustin: Institut Monumenta Serica. ISBN 3805005342.

- Moule, Arthur C., Christians in China before the year 1550, London, 1930

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042908765.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781907318047.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844, now in the public domain in the United States.

External links[]

- Church of the East in China