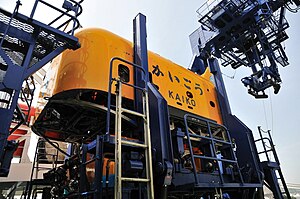

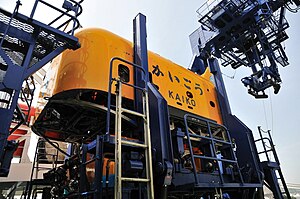

Kaikō ROV

Kaikō

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner | The Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) |

| Operator | JAMSTEC |

| Laid down | 1991[1] |

| Launched | 1993[1] |

| Christened | 1993[1] |

| Completed | 1993[1] |

| Commissioned | 1993[1] |

| Maiden voyage | May 1993 to March 1995[1] |

| Out of service | 2003 |

| Stricken | 2003 |

| Homeport | Yokosuka, Japan |

| Fate | Lost at sea off Shikoku Island during Typhoon Chan-Hom, 29 May 2003[2] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | remotely operated underwater vehicle |

| Displacement | 10.6 tons in air[3] |

| Length | 3.0 meters[3] |

| Installed power | electrical (Lithium-ion batteries) |

| Test depth | 10911.4 meters |

| Complement | unmanned |

| Sensors and processing systems | side-scan sonar and search lights |

Kaikō (海溝, "Ocean Trench") was a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) built by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) for exploration of the deep sea. Kaikō was the second of only five vessels ever to reach the bottom of the Challenger Deep, as of 2019. Between 1995 and 2003, this 10.6 ton unmanned submersible conducted more than 250 dives, collecting 350 biological species (including 180 different bacteria), some of which could prove to be useful in medical and industrial applications.[3] On 29 May 2003, Kaikō was lost at sea off the coast of Shikoku Island during Typhoon Chan-Hom, when a secondary cable connecting it to its launcher at the ocean surface broke.[2]

Another ROV, Kaikō7000II, served as the replacement for Kaikō until 2007. At that time, JAMSTEC researchers began sea trials for the permanent replacement ROV, ABISMO (Automatic Bottom Inspection and Sampling Mobile). ABISMO is currently one of only two ROVs rated to 11,000-meters (the other being Deepsea Challenger, piloted by director James Cameron).

Challenger Deep[]

Bathymetric data obtained during the course of the expedition (December 1872 – May 1876) of the British Royal Navy survey ship HMS Challenger enabled scientists to draw maps,[4] which provided a rough outline of certain major submarine terrain features, such as the edge of the continental shelves and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This discontinuous set of data points was obtained by the simple technique of taking soundings by lowering long lines from the ship to the seabed.[5]

Among the many discoveries of the Challenger expedition was the identification of the Challenger Deep. This depression, located at the southern end of the Mariana Trench near the Mariana Islands group, is the deepest surveyed point of the World Ocean. The Challenger scientists made the first recordings of its depth on 23 March 1875 at station 225. The reported depth was 4,475 fathoms (8184 meters) based on two separate soundings.

On 23 January 1960, Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard were the first men to descend to the bottom of the Challenger Deep in the Trieste bathyscaphe. Though the initial report claimed the bathyscaphe had attained a depth of 37,800 feet,[6] the maximum recorded depth was later calculated to be 10,911 metres (35,797 ft). At this depth, the water column above exerts a barometric pressure of 108.6 megapascals (15,750 psi), over one thousand times the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level. Even at this great depth and pressure, a small flounder-like fish was seen moving away from the spotlight of the bathyscaphe. Since then, only one manned vessel has ever returned to the Challenger Deep, the Deepsea Challenger, which was piloted by director James Cameron on March 26, 2012 to the bottom of the trench.[7]

In March 1995, Kaikō became the second vessel ever to reach the bottom of the Challenger Deep, and the first craft to visit this location since the Trieste mission.[3][8] The maximum depth measured on that dive was 10,911.4 meters,[1][8][9] marking the deepest dive for an unmanned submersible to date. On 31 May 2009, Nereus became the third vessel to visit the bottom of the Challenger Deep, reaching a maximum recorded depth of 10,902 meters.[8][10]

RV Kairei[]

RV Kairei (かいれい) is a deep sea research vessel that served as the support ship for Kaikō, and for its replacement ROV, Kaikō7000II. It now serves as the support ship for ABISMO. Kairei uses ABISMO to conduct surveys and observations of oceanic plateaus, abyssal plains, oceanic basins, submarine volcanoes, hydrothermal vents, oceanic trenches and other underwater terrain features to a maximum depth of 11,000 meters. Kairei also conducts surveys of the structure of deep sub-bottoms with complicated geographical shapes in subduction zones using its on-board multi-channel reflection survey system.[11]

Timeline and fate of Kaikō[]

In February 1996, Kaikō returned to Challenger Deep, this time collecting sediment and microorganisms from the seabed at a depth of 10,898 meters. Among the novel organisms identified and collected was [12] and Shewanella benthica.[13] These two species of bacteria appear to be obligately barophilic. The optimal pressure conditions for growth of S. benthica is 70 Megapascals (MPa), while M. yayanosii grows best at 80 MPa; no growth at all was detected at pressures of less than 50 MPa with either strain.[13] Both species appear to contain high levels of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), omega-3 fatty acids which could prove to be useful in the treatment of hypertension and even cancer.[3]

In December 1997, Kaikō located the wreck of Tsushima Maru on the sea floor off the coast of Okinawa. Tsushima Maru was an unmarked Japanese passenger/cargo ship that was sunk during World War II by USS Bowfin, a United States Navy submarine.

In May 1998, Kaikō returned again to Challenger Deep, this time collecting specimens of Hirondellea gigas. Hirondellea gigas (Birstein and Vinagradov, 1955) is a crustacean of the Uristidae family of marine amphipods.[14]

In October 1999, Kaikō performed a robotic mechanical operation at a depth of 2,150 meters off the coast of Okinawa near the Ryukyu Trench, connecting measuring equipment with underwater cables on the sea floor. On this mission, another bacterial species, Shewanella violacea, was discovered at a depth of 5,110 meters.[15] This organism is notable for its brilliant violet-colored pigment. Certain compounds found in S. violacea may have applications in the cosmetics industry (development of products for lightening of skin tone) and also in the semiconductor industry (development of chemicals to be used in production of semiconductors).[3]

In late November 1999, Kaikō located the wreckage of H-2 No. 8, a NASDA rocket (satellite launch system), on the sea floor at a depth of 2,900 meters off the Ogasawara Islands. H-2 flight F8 was conducted on 15 November 1999. The rocket, which was carrying a Multi-Functional Transport Satellite (MTSAT) payload, self-destructed after experiencing an engine malfunction shortly after it was launched.

In August 2000, Kaikō discovered hydrothermal vents and their associated deep sea communities at a depth of 2,450 meters near the Central Indian Ridge. The Central Indian Ridge is a divergent tectonic plate boundary between the African Plate and the Indo-Australian Plate located in the western Indian Ocean.

On 29 May 2003, Kaikō was lost at sea during Typhoon Chan-Hom, when a steel secondary cable connecting it to its launcher at the surface broke off the coast of Shikoku Island.[2]

In May 2004, JAMSTEC resumed its research operations, using a converted ROV as its vehicle. The ROV, formerly known as UROV 7K, was rechristened Kaikō7000II. The 7000 designation indicates that this vessel is rated for diving to a maximum depth of 7,000 meters.

Development of ABISMO[]

While the temporary replacement ROV (Kaikō7000II) has a remarkable performance record, it is only rated to 7,000 meters and cannot reach the deepest oceanic trenches. For this reason, JAMSTEC engineers began work on a new 11,000-meter class of ROV in April 2005.[2][16] The project is called ABISMO (Automatic Bottom Inspection and Sampling Mobile), which translates to abyss in Spanish. Initial sea trials of ABISMO were conducted in 2007. The craft successfully reached a planned depth of 9,760-meters, the deepest part of Izu–Ogasawara Trench, where it collected core samples of sediment from the seabed.[2][16] Plans are underway for a mission to the Challenger Deep.[citation needed]

See also[]

- MIR – Self-propelled deep submergence vehicle

- Shinkai – Manned research submersible

- Explorer – Autonomous underwater vehicle from People's Republic of China

- Nereus – Hybrid remotely operated or autonomous underwater vehicle

- ABISMO ROV – Japanese remotely operated underwater vehicle for deep sea exploration

- Autonomous underwater vehicle – Unmanned underwater vehicle with autonomous guidance system

- Bathymetry – Study of underwater depth of lake or ocean floors

- Deep sea – Lowest layer in the ocean, below the thermocline and above the seabed, at a depth of 1000 fathoms (1800 m) or more

- Deep-submergence vehicle – Deep-diving manned submarine that is self-propelled

- Diving chamber – Hyperbaric pressure vessel for human occupation used in diving operations

- Timeline of diving technology – Chronological list of notable events in the history of underwater diving equipment

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h M. Kyo; E. Hiyazaki; S. Tsukioka; H. Ochi; Y. Amitani; T. Tsuchiya; T. Aoki; S. Takagawa (October 1995). "The sea trial of "KAIKO", the full ocean depth research ROV". OCEANS '95. MTS/IEEE. Challenges of Our Changing Global Environment (Conference Proceedings). 3. San Diego, California. pp. 1991–1996. doi:10.1109/OCEANS.1995.528882. ISBN 978-0-933957-14-5. S2CID 110932870.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Shōjirō Ishibashi; Hiroshi Yoshida (March 2008). "Developing a Sediment Sampling ROV for the Deepest Ocean". Sea Technology. Retrieved 27 June 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Suvendrini Kakuchi (21 July 2003). "The Underwater Wonders Revealed by Kaiko". Tierramérica: Environment & Development. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ John Murray; Rev. A.F. Renard (1891). Report of the scientific results of the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873 to 1876. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 525. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ John Murray; Rev. A.F. Renard (1891). Report on the Deepsea Deposits based on the Specimens Collected during the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger in the years 1873 to 1876. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 525. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Press Release, Office of Naval Research (February 1, 1960). "Research Vessels: Submersibles – Trieste". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 18 April 2002. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ National Geographic (25 March 2012). "James Cameron Now at Ocean's Deepest Point". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Robot sub reaches deepest ocean". BBC News. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b JAMSTEC (2007). "Maximum depth reached by Kaikō". Yokosuka, Japan: Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ University of Hawaii Marine Center (4 June 2009). "Daily Reports for R/V KILO MOANA June & July 2009". Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ JAMSTEC (2007). "Deep Sea Research Vessel KAIREI". Yokosuka, Japan: Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Y. Nogi; Chiaki Kato (January 1999). "Taxonomic studies of extremely barophilic bacteria isolated from the Mariana Trench and description of Moritella yayanosii sp. nov., a new barophilic bacterial isolate". Extremophiles. 3 (1): 71–77. doi:10.1007/s007920050101. PMID 10086847. S2CID 9565878.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chiaki Kato; Lina Li; Yuichi Nogi; Yuka Nakamura; Jin Tamaoka; Koki Horikoshi (April 1998). "Extremely Barophilic Bacteria Isolated from the Mariana Trench, Challenger Deep, at a Depth of 11,000 Meters". Appl Environ Microbiol. 64 (4): 1510–1513. doi:10.1128/AEM.64.4.1510-1513.1998. PMC 106178. PMID 9546187.

- ^ "Hirondellea". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Yuichi Nogi; C. Kato; Koki Horikoshi (September 1998). "Taxonomic studies of deep-sea barophilic Shewanella strains and description of Shewanella violacea sp. nov". Archives of Microbiology. 170 (5): 331–338. doi:10.1007/s002030050650. PMID 9818352. S2CID 22472007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kazuaki Itoh; Tomoya Inoue; Junichiro Tahara; Hiroyuki Osawa; Hiroshi Yoshida; Shōjirō Ishibashi; Yoshitaka Watanabe; Takao Sawa; Taro Aoki (10–14 November 2008). "Sea Trials of the New ROV ABISMO to Explore the Deepest Parts of Oceans" (PDF). Proceedings of the Eighth (2008) ISOPE Pacific/Asia Offshore Mechanics Symposium. Bangkok, Thailand: The International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-880653-52-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

Further reading[]

- Takai, K., A. Inoue and K. Horikoshi (1999). "Thermaerobactor Marianensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an Aerobic Extremely Thermophilic Marine Bacterium from the 11,000 Meter-Deep Mariana Trench". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 49 (2): 619–628. doi:10.1099/00207713-49-2-619. PMID 10319484.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[]

- JAMSTEC's Kaikō page

- Marine Biology: The Deep Sea – General resource on deep sea creatures

- Autonomous Benthic Explorer AUV (ABE)

- R.I.P. A.B.E: The pioneering Autonomous Benthic Explorer is lost at sea

- Deep sea fish

- Marine biology

- Research submarines of Japan

- Physical oceanography

- Remotely operated underwater vehicles

- Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology