Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic)

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (July 2019) |

Kingdom of Naples | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806–1815 | |||||||||

Flag (1811–1815)

Medium Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Client state of the French Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Naples | ||||||||

| Common languages | Italian, Neapolitan, French | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1806–1808 | Joseph I | ||||||||

• 1808–1815 | Joachim-Napoleon | ||||||||

| Historical era | Napoleonic Wars | ||||||||

• Proclamation | 30 March 1806 | ||||||||

• Joseph Bonaparte enters Naples | 15 February 1806 | ||||||||

| 10 March 1806 | |||||||||

• Joachim Murat replaces Joseph | 1 August 1808 | ||||||||

| 3 May 1815 | |||||||||

• Congress of Vienna | 9 June 1815 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

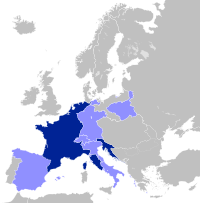

The Kingdom of Naples (Italian: Regno di Napoli; Neapolitan: Regno 'e Napule; French: Royaume de Naples) was a French client state in southern Italy created in 1806 when the Bourbon Ferdinand IV & VII of Naples and Sicily sided with the Third Coalition against Napoleon and was in return ousted from his kingdom by a French invasion. Joseph Bonaparte, elder brother of Napoleon I, was installed in his stead: Joseph conferred the title "Prince of Naples" to be hereditary on his children and grandchildren. When Joseph became King of Spain in 1808, Napoleon appointed his brother-in-law Joachim Murat to take his place. Murat was later deposed by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 after striking at Austria in the Neapolitan War, in which he was decisively defeated at the Battle of Tolentino.

Although the Napoleonic kings were officially styled King of Naples and Sicily, British domination of the Mediterranean made it impossible for the French to gain control of Sicily, where Ferdinand had fled, and French power was confined to the mainland Kingdom of Naples alone while Ferdinand continued to reside in and rule the Kingdom of Sicily.

In the modernising spirit of the French Revolution, the regimes of Joseph and Murat implemented a programme of sweeping reforms to the organisation and structure of the ancient feudal kingdom. On 2 August 1806 Feudalism was abolished and all the rights and privileges of the nobility suppressed.[1] The practice of tax-farming was also ended and the collection of all taxes slowly brought under direct central control as the government brought-out the contractors and compensated those who had lost their feudal tax-collecting privileges with bonds.[2] The first public street-lighting system, modelled on that of Paris, was also installed in the city of Naples during Joseph's reign.

Continuing the anti-clerical sentiment of the Revolution, Church property was confiscated en masse and auctioned off as Biens nationaux (in compensation for the loss of feudal privileges, the nobles received a certificate which could be exchanged for such properties). However, not all church land was sold immediately, with some retained to support charitable and educational foundations.[3] Most monastic orders were also suppressed and their funds transferred to the royal treasury, however, although both the Benedictines and Jesuits were dissolved, Joseph preserved the Franciscans.[4]

In 1808 Joachim Murat, husband of Napoleon's sister Caroline, was granted the crown of Naples by the Emperor after Joseph had reluctantly accepted the throne of Spain. Murat joined Napoleon in the disastrous campaign of 1812 and, as Napoleon's downfall unfolded, increasingly sought to save his own kingdom. Opening communications with the Austrians and British, Murat signed a treaty with the Austrians on January 11, 1814 in which, in return for renouncing his claims to Sicily and providing military support to the Allies in the war against his former Emperor, Austria would guarantee his continued possession of Naples.[5] Marching his troops north, Murat's Neapolitans joined the Austrians against Napoleon's stepson, Eugene de Beauharnais, Viceroy of the Kingdom of Italy. After initially opening secret communications with Eugene to explore his options of switching sides again, Murat finally committed to the allied side and attacked Piacenza.[6] Upon Napoleon's abdication on 11 April 1814 and Eugene's armistice, Murat returned to Naples, however his new allies trusted him little and he became convinced that they were about to depose him. Upon Napoleon's return in 1815, Murat struck out from Rimini at the Austrian forces in northern Italy, in what he considered a pre-emptive attack. The powers at the Congress of Vienna assumed he was in concert with Napoleon, but this was in fact the opposite of the truth, as Napoleon was then seeking to secure recognition of his return to France through promises of peace, not war. On 2 April Murat entered Bologna without a fight, but soon he was in headlong retreat as the Austrians crossed the Po at Occhiobello and his Neapolitan forces disintegrated at the first sign of a skirmish. Murat withdrew to Cesena, then Ancona, then Tolentino.[7] At the Battle of Tolentino on 3 May 1815 the Neapolitan army was swept aside and, though Murat escaped to Naples, his position was irrecoverable and he soon continued his flight, leaving Naples for France. Ferdinand IV & VI was soon restored and the Napoleonic kingdom came to an end. The Congress of Vienna confirmed Ferdinand in possession of both his ancient kingdoms, Naples and Sicily, but under the new unified title of King of the Two Sicilies, which would survive until 1861.

State symbols[]

1806–1808

Flag of Naples changed after Joseph Bonaparte became king.

1808–1811

Flag of Naples changed after Joachim Murat became king.

1811–1815

Flag of Naples changed

Civil ensign

Great Coat of arms

1806–1808

Joseph Bonaparte

Great Coat of arms

1808–1815

Joachim Murat

Sources[]

- Giuliano Procacci, History of the Italian People, London: 1970.

- Owen Connelly, Napoleon's Satellite Kingdoms, London: 1965.

Notes[]

- Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic)

- Former countries