Kiradjieff brothers

Tom Kiradjieff and John Kiradjieff were American restaurateurs credited for their creation of a regional specialty dish known as the Cincinnati chili.

History[]

The brothers were born in the town of Hrupishta,[1] then in the Ottoman Empire,[note 2][2] by Bulgarian parents.[3][note 3][4][5] The town was annexed during the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) by Greece. The partition of the Ottoman lands of the region of Macedonia between the Balkan nation-states resulted in the fact, that some of the Slavic speakers of Ottoman Macedonia emigrated to Bulgaria, or left the area.[6]

Athanas (Tom) was born in 1892, during the First World War, he was a soldier in the Bulgarian Army. In 1917 he was dismissed and moved to the Bulgarian capital Sofia, where he worked for a time as an accountant.[3] His little brother Ivan (John) born in 1895 had served also some time with the Bulgarian army.[1] In 1921 both emigrated to the United States.

They settled initially in New York,[7] but after selling hot dogs there for some time, the brothers followed their big brother Argir (Argie) to Cincinnati. Born in 1880, he was a cashier of the Bulgarian Exarchate Church-School Board in Hrupishta.[8] Argie had settled in Cincinnati by 1918, where he opened a grocery store.[9] In Cincinnati the brothers began to develop their own business. Tom got a job as a bank clerk and worked at night, cooking chili for the customers in his brother's place. It was at this time that Tom invented the regional specialty known as Cincinnati chili.

In 1922 they opened a hot dog stand located next to a burlesque theater called the Empress, which they named their business after. Tom and John returned to Bulgaria to find wives, while Argir went to his homeland for this purpose. Argir stayed there for several years, and when he came back, his two brothers were well established and provided him a job as a cashier. According to the journalist Vasil Stefanov,[note 4] in 1933 the Kiradjieff brothers were among the most successful Bulgarians in the city.[note 5][note 6][note 7][10][11][12][3][1][13][14][15][16][17] owners of a large and modern restaurant in the city center.[18]

Argir's wife did not adapt to America, and they moved back to Macedonia in the 1940s.[note 8][1][19] The Empress Chili grew to become a local chain. In 1959, the Kiradjieffs of Empress Chili, announced they be the first to come up with a new design for drive in, car-service. The last man who ran the family business was Tom's son Assen (Joe) Kiradjieff. Since the late 1950s, when his father's health sharply declined, Joe operated the Empress Chili. Tom died in 1960, while John had died in 1953. Later the Empress chain had a single surviving outlet. In 2009, 79-year-old Joe retired and sold the Empress Chili.[20]

Gallery[]

Ivan Kiradjieff and his little brother Ilia in Bulgarian military uniform.

Bulgarian soldiers during WWI. Ivan Kiradjieff is third from left.

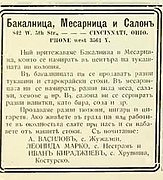

Advertising from Cincinnati, published in Bulgarian. One of the signed partners is Ivan Kiradjieff.

Ivan Kiradjieff and his Bulgarian wife Mila Gandeva in Paris.

Ivan Kiradjieff posing in Empress Chili in Cincinnati.

Advertisement with Argir Kiradjieff published in Bulgarian newspaper Naroden Glas.[note 9]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ This photo of the Kiradjieff brothers dated May 29, 1921, was taken at Maly's Studio on 635 Vine Street.

- ^ According to the statistics of Vasil Kanchov ("Macedonia. Ethnography and Statistics") in 1900 the Ottoman Hrupishta had 2690 inhabitants, of which 1100 Bulgarians, 700 Turks, 720 Aromanians and 170 Gypsies.

- ^ According to IMARO revolutionaries Georgi Hristov (1876-1964) and Kiryak Shkurtov, the father of the Kiradjhieff brothers Kostadin, was among the leading members of the Bulgarian community in the town.

- ^ Vasil Stefanov (1879 - 1950) was a Bulgarian publicist from Bitola, today in North Macedonia, publisher of the newspaper Naroden Glas (1907 - 1950) in the USA.

- ^ The Kiradjieff brothers have been described often as Bulgarians by different experts. The anthropologist, Timothy Charles Lloyd, explicitly has mentioned: "the Kiradjieffs, who are from Macedonia, consider themselves to be Bulgarian". Per another anthropologist, Claude Fischler: Cincinnati chili was invented by Tom Kiradjieff, a Bulgarian immigrant who was born in Macedonia. According to the folklorist Lucy M. Long: After World War II, Kiradjieff began expanding the Empress parlor with his son, Joe, but it remained a family business and emphasized its American rather than its ethnic identity, which they considered to be Bulgarian. S. Frederick Starr, a political scientist has claimed they were born in Macedonia, of Bulgarian parents. In a 2019 video-interview, the US Army veteran, and last owner of the Empress, Joe Kiradjieff has described his parents as Bulgarian and Macedonia as part of Bulgaria. (click on the external link at the bottom of this article). To this day, the Bulgarian community in Cincinnati respects them as its famous historical members. On the other hand according to the cultorologist Victor Roudometof: "It is clear that even in the pre-1945 period a large segment of Macedonia's Slavs declared themselves to be "Macedonians," although it would be completely premature to assume that this label stood for a national, as opposed to a regional identity."

- ^ According to other researchers they were Slavic Macedonians or simply Macedonians. For example, one of them, the food etymologist Dann Woellert, has insisted that in the first half of 20th century they were identified as Bulgarians, but that ethnic designation is not correct, and adds that the next generations of Cincinnati Kiradjieffs identified not only with their Bulgarian heritage, but also with their Slavic-Macedonian heritage, without explaining what was the case. Another example is the culinarian Adrienne Hall, who has described the Cincinnati chili as part of the Macedonian cuisine, but clarifies that most of the early Macedonian immigrants in the US identified as Bulgarians, describing the interwar Macedonian Americans as Macedonian Bulgarians. Finally, according to the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups: Until World War II almost all of Macedonian immigrants thought of themselves as Bulgarians and identified themselves as Bulgarians or Macedonian Bulgarians...The greatest advances in the growth of a distinct Macedonian-American community have occurred since the late 1950s. The new immigrants came from Yugoslavia's Socialist Republic of Macedonia, where since World War II they had been educated to believe that Macedonians composed a culturally and linguistically distinct nationality; the historic ties with Bulgarians in particular were deemphasized. These new immigrants not only are convinced of their own Macedonian national identity but also have been instrumental in transmitting these feelings to older Bulgarinan-oriented immigrants from Macedonia.

- ^ A few authors maintain even Kiradjieffs were Greek Macedonian, because they emigrated when their home town was already ceded to Greece. Moreover some of their closest relatives remained to live there. For those Kiradjieffs who stayed back in northern Greece, they changed their names to fit in with the Greek state policy of Hellenization and the ban of any Slavic legacy. A fourth brother, the youngest, Ilia Kiradjieff (1892-1982) stayed back and his new name became Ilias Kyratzis. None of these Kiradjieffs has visited Cincinnati to meet his relatives there. Such people of Greek persuasion are sometimes called by the pejorative term "Grecomans" by the other side. Greek sources most often refer to them as "Slavophones". Nevertheless, Ilia served in Bulgarian Army during WWI, and was among the sympathizers of the pro-Bulgarian Ohrana detachment, formed in the town during the Axis occupation of Greece in World War II.

- ^ It is not clear when exactly they moved back and which country was their destination. In 1940, this region's northern parts belonged to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, while the southern parts belonged to the Kingdom of Greece. Between 1941 and 1944 the Yugoslav area and some parts of Greek Macedonia were annexed by the Kingdom of Bulgaria. In 1945 the northern part became a new Yugoslav Republic, while in the southern part broke out the Greek Civil War. The northeastern part remained under Bulgaria during the whole period.

- ^ Naroden Glas was a Bulgarian newspaper, an agency of the Macedonian Bulgarian emigrants to the United States. It was published in Bulgarian in the period from 1907 to 1950 in Granite City.

Footnotes[]

- ^ a b c d Woellert, Dann (2013). The Authentic History of Cincinnati Chili. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-992-1. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ Кѫнчовъ, Василъ. Македония. Етнография и статистика. София, Бѫлгарското книжовно дружество, 1900. ISBN 954430424X с. 267, (in Bulgarian).

- ^ a b c Starr, Frederick (1974). Princeton Alumni Weekly, Volume 75 (Best chili om earth). Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 9–11.

- ^ Markov, Georgi. Hrupishta. Memories. Bulgarian State Archives - Haskovo, Interface, 2002. p. 218, ISBN 954-90993-1-8. (in Bulgarian).

- ^ Киряк Шкуртов, Искреността на младотурците в сп. Илюстрация Илинден, кн. 2, София, февруари 1934 год., стр. 7-8. (in Bulgarian)

- ^ Palairet, Michael (2016). Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2, From the Fifteenth Century to the Present). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 178–180. ISBN 978-1443888493.

- ^ Donna R. Gabaccia, Donna R Gabaccia (2009) We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans Harvard University Press, Of Cookbooks and Culinary Roots, p. 109, ISBN 0674037448.

- ^ Markov, Georgi. Hrupishta. Memories. Bulgarian State Archives - Haskovo, Interface, 2002. p. 218, ISBN 954-90993-1-8. (in Bulgarian).

- ^ Covrett, Donna (2009). "Cincinnati Magazine (Heart burn)". Cincinnati, Ohio: Emmis Communications. p. 44 - 45.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help). - ^ Lloyd, Timothy Charles (January 1981). "The Cincinnati Chili Culinary Complex". Western Folklore. 40 (1): 28–40. doi:10.2307/1499846. JSTOR 1499846.

- ^ Claude Fischler, Chapter 40 (The “McDonaldization” of culture') in J.L. Flandrin and M. Montanari, eds., Food: A Culinary History, Arts and Traditions of the Table: European perspectives, publisher Columbia University Press, (2013) ISBN 023111155X, p. 544.

- ^ Cincinnati chilly an article by Lucy M. Long in Deutsch, Jonathan, Benjamin Fulton, and Alexandra Zeitz. (2018). We eat what?: a cultural encyclopedia of unusual foods in the United States. pp. 91-94. ISBN 1440841128.

- ^ Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar, eds. (1980). "Macedonians". Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Harvard University Press. pp. 690–694. ISBN 0674375122. OCLC 1038430174.

The Macedonians.

- ^ Victor Roudometof (2007) Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 109, ISBN 0275976483.

- ^ Patricia Schultz (2016) 1,000 Places to See in the United States and Canada Before You Die, 3th edition Workman Publishing, p. 559, ISBN 0761189432.

- ^ Adrienne Hall "Macedonia", pp. 392–95. in Ethnic American Food Today: A Cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 2, with Lucy M. Long as edidor, Rowman & Littlefield (2015); ISBN 1442227311.

- ^ Шандански, Ив. Въоръжената самозащита на българите в Егейска Македония (март – септември 1943 г.), стр. 54 в Известия на Държавните архиви, кн. 94, 2007, стр. 34–95, (in Bulgarian).

- ^ Vasil Stefanov, 25th anniversary jubilee almanac of the newspaper "Naroden Glas": the oldest Bulgarian national newspaper in America: 1908-1933, p. 364. (in Bulgarian).

- ^ Thanos Veremis (2017) A Modern History of the Balkans: Nationalism and Identity in Southeast Europ, Bloomsbury Publishing, Chapter VII. From War to Communism, pp. 58-67, ISBN 1786731053.

- ^ Covrett, Donna (2009). "Cincinnati Magazine (Heart burn)". Cincinnati, Ohio: Emmis Communications. p. 64 - 66.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help).

External link[]

- People from Argos Orestiko

- People from Salonica vilayet

- Macedonian Bulgarians

- Bulgarian emigrants to the United States

- Bulgarians from Aegean Macedonia

- Macedonian emigrants

- American people of Macedonian descent

- Macedonian businesspeople