Knaresborough Castle

| Knaresborough Castle | |

|---|---|

| Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, England | |

The ruins of the keep of Knaresborough Castle. | |

Knaresborough Castle | |

| Coordinates | 54°00′26″N 1°28′10″W / 54.00719°N 1.46932°WCoordinates: 54°00′26″N 1°28′10″W / 54.00719°N 1.46932°W |

| Type | Castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Duchy of Lancaster |

| Controlled by | Harrogate Borough Council |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | Around 1100, rebuilt 1301–1307 |

| In use | Until 1648 |

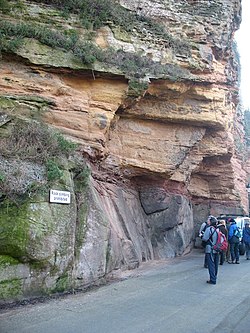

Knaresborough Castle is a ruined fortress overlooking the River Nidd in the town of Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, England.

History[]

The castle was first built by a Norman baron in c. 1100 on a cliff above the River Nidd. There is documentary evidence dating from 1130 referring to works carried out at the castle by Henry I.[1] In the 1170s Hugh de Moreville and his followers took refuge there after assassinating Thomas Becket.

In 1205 King John took control of Knareborough Castle.[2] He regarded Knaresborough as an important northern fortress and spent £1,290 on improvements to the castle.[3] The castle was later rebuilt at a cost of £2,174 between 1307 and 1312 by Edward I and later completed by Edward II, including the great keep.[4] Edward II gave the castle to Piers Gaveston and stayed there himself when the unpopular nobleman was besieged at Scarborough Castle.[5]

Philippa of Hainault took possession of the castle in 1331, at which point it became a royal residence.[5] The queen often spent summers there with her family. Her son, John of Gaunt acquired the castle in 1372, adding it to the vast holdings of the Duchy of Lancaster. Katherine Swynford, Gaunt's third wife, obtained the castle upon his death.[6]

A detailed survey of the state of the castle buildings was made in 1561. The building was used by estate auditors and law courts were held in the hall.[7]

The castle was taken by Parliamentarian troops in 1644 during the Civil War and largely destroyed in 1648, not as the result of warfare but because of an order from Parliament to dismantle all Royalist castles.[8] Indeed many town-centre buildings are built of 'castle stone'.

Present day[]

The remains of the castle are open to the public and there is a charge for entry to the interior remains. The grounds are used as a public leisure space, with a bowling green and putting green open during summer. It is also used as a performing space, with bands playing most afternoons through the summer. It plays host to frequent events, such as the annual FEVA (Festival of Visual Arts and Entertainment).[9] The property is owned by the monarch as part of the Duchy of Lancaster holdings, but is administered by Harrogate Borough Council.

Knaresborough castle has had ravens since 2000, one of which was given by the Tower of London, and an African pied crow named Mourdour.[10] In 2018, Mourdour was filmed greeting people at the castle in a Yorkshire accent, saying "Y'alright love?" The video subsequently went viral and was reported by various news broadcasters.[11][12][13]

Description[]

The castle, now much ruined, comprised two walled baileys set one behind the other, with the outer bailey on the town side and the inner bailey on the cliff side. The enclosure wall was punctuated by solid towers along its length, and a pair, visible today, formed the main gate. At the junction between the inner and outer baileys, on the north side of the castle stood a tall five-sided keep, the eastern parts of which have been pulled down. The keep had a vaulted basement, at least three upper stories, and served as a residence for the lord of the castle throughout the castle's history. The castle baileys contained residential buildings, and some foundations have survived. In 1789, historian Ely Hargrove wrote that the castle contained "only three rooms on a floor, and measures, in front, only fifty-four feet."[14]

The upper storey of the Courthouse features a museum that includes furniture from the original Tudor Court, as well as exhibits about the castle and the town.[1] Some of the surviving areas of the castle keep wall also bear impact scars left by bullets fired during the Civil War siege.

References[]

- Notes

- ^ a b "History of Knaresborough". knaresborough.co.uk. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Brown 1959, p. 256

- ^ Cryer, Clare. "History of Knaresborough Castle and Museum". www.harrogate.gov.uk. Harrogate Borough Council. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ King 1983, pp. 520, 537

- ^ a b "Knaresborough Castle – Yorkshire". www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Grainge, William (1871). The History and Topography of Harrogate, and the Forest of Knaresborough. J.R. Smith. p. 67.

- ^ The Diary of Sir Henry Slingsby of Scriven (London, 1836), pp, 239-243.

- ^ Kellet, Arnold (15 July 2011). A to Z of Knaresborough History. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445626406.

- ^ "Knaresborough Festival". feva.info. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Hustwitt Skelton, Igraine. "Knaresborough Castle Ravens". knaresboroughcastleravens. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ "Crow with Yorkshire accent caught on film". BBC News. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Chalmers, Graham. "Viral sensation: Talking crows in Knaresborough set the tongues wagging". The Harrogate Advertiser. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Barrie, Josh (12 July 2018). "This is the woman who trains ravens to talk with a Yorkshire accent". iNews. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Hargrove, Ely (1789). The history of the castle, town, and forest of Knaresborough, with Harrogate and its medicinal waters. W. Blanchard. pp. 199.

- Bibliography

- Brown, R. Allen (April 1959), "A List of Castles, 1154–1216", The English Historical Review, Oxford University Press, 74 (291): 249–280, doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxiv.291.249

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset, The David & Charles Book of Castles, David & Charles, 1980, p. 249. ISBN 0-7153-7976-3

- King, David James Cathcart (1983), Catellarium Anglicanum: An Index and Bibliography of the Castles in England, Wales and the Islands. Volume I: Anglesey–Montgomery, Kraus International Publications

External links[]

- Knaresborough Castle & Museum - official site at Harrogate Borough Council

- Knaresborough Castle on castlexplorer.co.uk

- Tourist attractions in North Yorkshire

- Castles in North Yorkshire

- Ruins in North Yorkshire

- Museums in North Yorkshire

- Local museums in North Yorkshire

- Knaresborough

- De Vesci family