Knightriders

| Knightriders | |

|---|---|

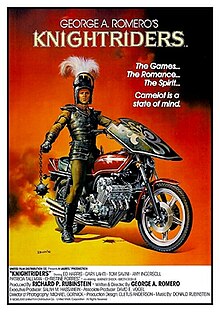

Original theatrical poster by Boris Vallejo | |

| Directed by | George A. Romero |

| Written by | George A. Romero |

| Produced by | Richard P. Rubinstein |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Michael Gornick |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Donald Rubinstein |

Production company | Laurel Entertainment |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 145 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Knightriders is a 1981 American drama film written and directed by George A. Romero and starring Ed Harris, Gary Lahti, Tom Savini, Amy Ingersoll, Patricia Tallman, and Christine Forrest. It was filmed entirely on location in the Pittsburgh metro area, including Fawn Township and Natrona during the summer of 1980.[2]

The film represents a change of pace for Romero, known primarily for his horror films; it is a personal drama about a travelling renaissance fair troupe.[3]

Plot[]

Billy leads a traveling troupe that jousts on motorcycles. "King William", as he styles himself, tries to lead the troupe according to his Arthurian ideals. However, the constant pressure of balancing those ideals against the modern day realities and financial pressures of running the organization are beginning to strain the group. Billy is also plagued by a recurring dream of a black bird. Tensions are exacerbated by Billy's constantly pushing himself despite being injured and the arrival of a promoter named Bontempi, who wants to represent the troupe.

After Billy spends a night in jail watching a member of his troupe beaten because Billy has refused a payoff to a corrupt local cop, Billy returns to the fairground where the troupe is next to perform and is shocked that some members want to join with the promoter. His sense of betrayal is heightened when his queen, Linet, admits that her feelings for him may not be the reason she remains with the troupe.

Things come to a head after Morgan, leader of the dissident faction who believes he should be king, wins the day's tournament and a fight breaks out between the troupe and rowdy members of the crowd. Billy faces an Indian rider with a black eagle crest on his breast plate, the black bird of his dreams. Billy defeats the Indian but aggravates his injury; later commissioning the Indian as a knight in his troupe. Morgan and several other riders leave the troupe to follow Bontempi. Billy's loyal supporter Alan also departs with his new girlfriend Julie and friend Bors to try to sort out his emotions. Billy and the remainder of the troupe settle at the fairground to await the dissidents' return.

Troupe member Pippin comes to terms with his homosexuality and finds love with Punch. Alan's girlfriend, Julie, has run away from home to escape her alcoholic and abusive father and her weak-willed mother. While Alan is soul searching, he realizes Julie is using him as an escape and that he really desires Billy's Queen Linet. Alan takes a confused and hurt Julie home to her parents.

Meanwhile, Morgan's riders succumb to infighting. Alan finds Morgan and helps him realize that there can only be one king and he sees about signing with Bontempi. However, after seeing rowdy drunken behavior in his friends, Morgan and his riders return to Billy's fair to challenge for the crown. Billy announces his retirement and sets forth the rules: all knights compete, and any man knocked off his motorcycle is out. Morgan is victorious, and is crowned king by Billy. Angie, the troupe's mechanic, is then crowned queen by Morgan, after he realizes she is the woman he loves. Linet finds love with Alan.

Billy leaves the troupe, accompanied by the silent eagle-crested knight, and returns to thrash the crooked cop. While riding again, Billy, weak and hallucinatory from loss of blood from his injury, has a vision of riding an actual horse. Immediately afterwards he is struck by an oncoming truck. The entire troupe gathers at Billy's funeral to say farewell to its fallen king.

Cast[]

- Ed Harris as King Billy

- John Amplas as Whiteface

- Gary Lahti as Sir Alan

- Tom Savini as Sir Morgan, The Black Knight

- Amy Ingersoll as Queen Linet

- Patricia Tallman as Julie Dean

- Brother Blue as Merlin, The Wizard

- Ken Foree as Little John

- Scott Reiniger as Sir Marhalt

- Martin Ferrero as Bontempi

- Warner Shook as Pippin

- Randy Kovitz as Punch

- Michael P. Moran as Deputy Cook

- Harold Wayne Jones as Sir Bors

- Albert Amerson as The Indian

- Christine Forrest as Angie, Morgan's Girlfriend

- Donald Rubinstein as The Lead Minstrel

- Stephen King as "Hoagie Man"

- Bingo O'Malley as Sheriff Rilly

- Greg Besnak as Rhino, Bald Mustachioed Head Biker

- Gary Davis as Biker (Rhino's Sidekick)

Production[]

A labor of love,[4] the film was initially conceived as a proper period piece which would portray the Middle Ages in a more realistic fashion.[5] it was rethought after Romero's experience working on racing documentaries.[5]

Romero has claimed the medieval hobbyist organization, the Society for Creative Anachronism, to be one inspiration for the film.[6] It was the first of three films financed and released through United Film Distribution.[4]

A shorter cut of the film (running 102 minutes) was released in Europe. In the movie's credits, the writer Stephen King is referred to as "Hoagie man," as he makes a few sarcastic comments during the troupe's first performance while munching on a large sandwich.

Critical reception[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (June 2019) |

Christopher John reviewed Knightriders in Ares Magazine #9 and commented that "[with] the exceptional soundtrack, excellent photography, sharp writing, directing and editing, let alone the performances of a well trained cast, it is worth the time and effort to see Knightriders. It is the best movie of 1981 so far."[7] Tony Williams, in his book The Cinema of George A. Romero, said "Knightriders is a highly personal and sincere film revealing Romero's Utopian ideals in a cinematically allegorical manner. Although flawed by its long running time and some over-emphatic dialogue scenes, it is nonetheless one of the directors's major achievements which deserves better recognition.[8] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Knightriders holds an approval rating of 77%, based on 13 reviews, and an average rating of 6.16/10.[9]

Soundtrack[]

The film score by Donald Rubinstein was released on Perseverance Records in 2008.

References[]

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ Blank, Ed (July 27, 1980). "No Horsing Around For These Knights". Pittsburgh Press. p. 221. Retrieved September 12, 2017 – via newspapers.com.

Site of filming is a limestone lot in Fawn Township.

- ^ Watt, Mike (July 17, 2017). "In memory of 'Night of the Living Dead' director George A. Romero". Pittsburgh City Paper. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ a b Thompson, Anne (July 16, 2017). "How George Romero's Semi-Autobiographical Labor of Love 'Knightriders' Gave Him the Independence He Wanted So Badly". IndieWire. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Kane, Joe (2010). Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever. Citadel Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8065-3331-5.

- ^ Aronstein, S. (April 30, 2016). "Old Myths Are New Again". Hollywood Knights: Arthurian Cinema and the Politics of Nostalgia. Springer. p. 135. ISBN 9781137124005. Retrieved September 12, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ John, Christopher (July 1981). "Film & Television". Ares Magazine. Simulations Publications, Inc. (9): 21–22, 29.

- ^ Williams, Tony. The Cinema of George A. Romero, Knight of the Living Dead, "Knightriders", Columbia University Press. (2003)

- ^ "Knightriders (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

External links[]

- 1981 films

- English-language films

- 1980s action drama films

- American action drama films

- American films

- American independent films

- Arthurian films

- Circus films

- 1980s English-language films

- Films directed by George A. Romero

- Films set in Pittsburgh

- Films shot in Pennsylvania

- Films shot in Pittsburgh

- Motorcycling films

- United Artists films

- 1981 drama films

- 1981 independent films