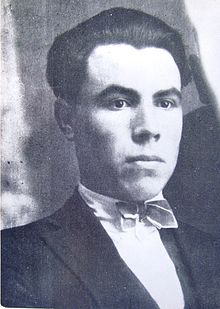

Kočo Racin

Kočo Racin | |

|---|---|

Кочо Рацин | |

| |

| Born | Kosta Apostolov Solev 21 December 1908 |

| Died | 13 June 1943 (aged 34) |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Macedonian |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Known for | Foundation of the modern Macedonian literature |

Kosta Apostolov Solev (Macedonian and Bulgarian: Коста Апостолов Солев; 22 December 1908 – 13 June 1943), primarily known as poet Kočo Racin[1] (Macedonian and Bulgarian: Кочо Рацин), was a Macedonian author and socialist activist who is considered a founder of modern Macedonian literature. Racin wrote in prose too and created some significant works with themes from history, philosophy, and literary critique. While he wrote also in standard Bulgarian language[2] and had some clearly pro-Bulgarian views,[3][4] he is regarded also a Bulgarian by some authors in Bulgaria.[5][6][7]

Biography[]

Early life[]

Kočo (Kosta Solev) Racin was born in 1908 in Veles, in the Kosovo Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia). He was raised in a very poor family. His father, Apostol was a potter who earned just enough to feed his family, and he could not support Racin financially in his education. Racin finished just one year in the local high school at the age of thirteen, and then worked in his father's pottery workshop.

Campaigner in the Communist movement[]

In 1924 he took part in KPJ, and in a short time, he positioned himself as one of the most-promising young members of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in Macedonia. In 1926, Racin became a member of the local Committee of KPJ in Veles, and in November 1928, he participated in the Fourth Congress of KPJ in Dresden as the only delegate from Macedonia. After returning to Yugoslavia he was arrested, but three months later he was freed because of insufficient evidence. In April 1929 he went into army service in Požarevac.

In 1929, the party organization in Macedonia collapsed. However, in 1932 the process for reuniting the party began, and in the summer of 1933, the Local Committee of KPJ in Macedonia was started, in which Nikola Orovčanec, Živoin Ćurcić and Racin participated. In November of the same year, LM started to issue the monthly newspaper "Iskra" (Spark), whose editor was Racin.[8] Only two editions of the newspaper were produced. In the beginning of January 1934, there was a break-in, and 15 leading Macedonian communists – together with Racin – were arrested. Racin was given 4 years in prison at Sremska Mitrovica, but in December 1935, he was given amnesty under a new law. His time in jail and the association with Moša Pijade, Rodoljub Čolaković and Ognjen Prica instilled in him faith in the importance of writing in his mother tongue (for Racin the Macedonian). Later he participated in the translation of the "Communist manifesto" into Macedonian.

The surname "Racin" comes from the name of his loved one, Rahilka Firfova-Raca.

Ascent and fall: "White Dawns" and expulsion from the party[]

After he came out of jail, Racin started writing poems and songs intensively. In 1939 he published his poem collection, entitled "White Dawns"[9] (in Macedonian: Бели мугри). He also wrote and published some articles and works with themes from history, philosophy and literary critique.

All of this made him the most famous Macedonian thinker and philosopher in Yugoslavia at that time. However the glory and authority that he enjoyed at that time would collapse in 1940, with a discord between him and the leadership of the KPJ in Macedonia. Because of the visit that Racin made to Aleksandar Cvetković (then leader of Vardar Banovina) and a single critical speech about the work of the KPJ Committee in Macedonia, Racin was expelled from the party. Its members were encouraged to boycott him. The boycott lasted until 1942, when the relationship between Racin and the party in Macedonia improved.

After the capitulation of Yugoslavia, for a period, he worked in Sofia, where he lived with his compatriot Kole Nedelkovski, who shared his thinking. After Nedelkovski's death, Racin returned to Skopje. In Skopje he was arrested by the Bulgarian police and interned in the village of Kornitsa.

Joining the Partisan movement and death[]

In 1943, Racin succeeded in getting back to Skopje. In the spring, he went to the Partisans, in the Korab detachment. He became an editor of the Partisan newspaper Ilindenski Pat. He also prepared two collections of Macedonian folklore songs.

Racin's life ended in a tragic way. On the night of 13 June 1943, when he was going back from the Partisan printing house on the mountain Lopušnik, Kičevo, he was mortally shot by the printing-house entrance guard. There are two theories about his death. According to the first (communist), it was an accident: Racin was born with some hearing defect, so he may not have heard the guard's call to stop and identify himself. According to the second version, Racin was murdered. In the opinion of his contemporaries, Strahil Gigov politically isolated Racin and organized his murder.[10]

Works[]

Starting in 1928, Kočo Racin wrote songs, stories, literary-historical articles, pieces for several magazines, literary critiques, and essays. In his essay "The Development of Our New Literature", he argued that the most correct and plausible way to develop modern literature in Macedonia was to build it from the inexhaustible riches of Macedonian folklore, combined with progressive social views. His most notable work was the small collection White Dawns (Beli mugri), which was published in Zagreb in 1939. Racin's interest lay in the plight of field and farm workers and wage earners.

Poetry[]

Racin started writing in 1928. From February until July he dedicated love verses to his loved one, Rahilka Firfova, on 31 cards and in the poem collection entitled Anthology of Pain (Macedonian: Антологија на болката). The 31 cards are kept today in the Archive of Macedonia. The songs are mainly written in Serbo-Croatian, except for six songs written in Bulgarian.

The same year, the Zagreb review Kritika published his first poem, "Hungry Sons" (Serbo-Croatian: Синови глади, "Sinovi gladi"). From May until October 1930, he published four poems in a Sarajevo journal. In 1932 in Skopje, Racin together with Jovan Gjorgjević and Aleksandar Aksić (students at the Skopje Faculty of Philosophy) published a poem collection in Serbian under the title 1932. This collection includes the poem "Firework" (Ватромет) one of Racin's most powerful poems.

The next published poem was "To a Worker" (Macedonian: До еден работник), which was his first poem in Macedonian. It was published in the Zagreb journal Književnik in 1936. In 1938, the poem "The Death of the Asturian Miner" (Смрт астуриског рудара) was published in honor of Gančo Hadzipanzov, a miner from Veles, who was killed in the Spanish Civil War.

His greatest success came with the publication of the poetry collection White Dawns in 1939. The collection was printed in 4,000 copies and sold all over Yugoslavia and Pirin Macedonia, with great success. The poem collection Macedonian People's Liberation Songs (Македонски народно-ослободителни песни) was published in 1943, but Racin was an editor rather than an author of the collection.

Prose[]

Racin's first manuscript was his prose confession Result (Резултат), published in 1928 in the Zagreb review Kritika. In 1932 he participated in the open competition "Literatura" from Zagreb. He was awarded for his story "In the Quarry" (У каменолому), which was later published in Kritika. In 1933, the same review published fragments from his novel Opium (in Macedonian translated as "Poppy", Афион). Racin started writing this novel around 1931, but the manuscript was lost during the break-in and his arrest. Other novels by Racin were: The Tobacco Pickers (Тутуноберачите) (1937), Noon (Пладне) (1937), One Life (Еден живот) (1937), Golden craft (Златен занает) (1939), and the novels Father (Татко) (1939) and Happiness Is Big, which were posthumously published.

History[]

Racin was interested in the historical theme of Bogomilism. He wrote three works dedicated to it: Dragovitian bogomils (Драговитските богомили), The Bogomils (Богомилите), and The Country Movement of the Bogomils in the Medieval Period (Селското движење на богомилите во Средниот век). From those three, only The country movement... was published during his lifetime, in 1939 in the review Folklore reader (Народна читанка). The work The Bogomils is written in Macedonian. Racin was the first Macedonian to study the Bogomil movement.

Philosophy[]

Racin was especially interested in the theory of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. As the result of it, he wrote and published some articles: "Hegel" (Хегел) published in the Zagreb Literatura review and "The meaning of Hegel's philosophy" published in the Belgrade review New culture (Нова култура) in 1939.

His relations with Malina Popivanova also sparked his interest in socialist feminism, which he described as a struggle for fundamental human rights.[11]

Literary criticism[]

In the field of literary criticism, Racin wrote the following works and articles: "The development and the meaning of our new literature" (Развитокот и значењето на една нова наша книжевност) (1940), "Angjelko Krstić in front of the court of Ž. Plamenac" (Анѓелко Крстиќ пред судот на Ж. Пламенац) (1939) and "The Realism of A. Krstić" (Реализмот на А. Крстиќ) (posthumously), "The Tired Nonsense about Mona Lisa's smile" (Блазираните глупости за насмевката на Мона Лиза) (1939) and "Art and the Working Class" (posthumously).

In honor of Racin[]

Starting in 1964, an annual Balkan literary festival was held in Racin's honor in his hometown, Veles. From 1992 the event has been Balkans-wide.

In 1952, Trajče Popov recorded the film poem "White Dawns" using the lyrics from his poem collection. In 2007 (on the day of his death), the movie Elegy for you (Елегија за тебе) was promoted. The authors of this video were Vasil Zafirčev and Dančo Stefkov.

See also[]

- White Dawns (1939)

References[]

- ^ Koco Racin Biography. Bookrags.com. Retrieved on 31 July 2014.

- ^ Пет стихотворения ("Рухнаха се надеждите мои"; "Плач в безмощие"; "И пак тъга раздира ми гърдите"; "Все пак"; "Мечти в полунощ") от Коста (Кочо) Рацин, написани на книжовен български език през 1928 г. във Велес.

- ^ According to the ethnographer Kosta Tsarnushanov, Racin claimed before the Second World War: We are Bulgarians and the name "Macedonian" is a comfortable cover for the struggle in today's conditions of Serbian terror. Коста Църнушанов, Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Унив. изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992. стр. 235-237.

- ^ There are reasonable doubts that Racin was purposefully liquidated, while suspect as an opportunist and pro-Bulgarian oriented communist by the Yugoslav partisans on the orders of Svetozar Vukmanovic-Tempo. For more see: Коста Църнушанов, Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Унив. изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992. стр. 235-237.

- ^ Ние сме си българи и името „македонец“ е удобно прикритие за борба в днешните условия на сръбски терор. For more see: Коста Църнушанов, Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Унив. изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992. стр. 235-237.

- ^ Сръбските гробокопачи на Македония успяха да унищожат физически човека Рацин. Поетът Рацин обаче не можаха да убият. Той и днес живее трайно в паметта на македонските българи, за които беше изпял песните си. For more see: Филимена В. Марковска, Кочо Рацин в моите спомени, откъс от неиздадените мемоари на авторката "Нем свидетел", в-к Дума, 12 Октомври 2013, брой 237.

- ^ Без съмнение е, че истината се намира у тези български писатели от Македония. По-точно. Времето от Миладинов до Рацин е онази рамка, в която обитава тази стара фаза. For more see: Венко Марковски, “Кръвта вода не става”, 1981 г. Издателството на Българската Академия на науките, София. гл. IV.

- ^ Koco Solev Racin. diversity.org.mk

- ^ Kosta Solev Racin – Beli Mugri. Cs.earlham.edu. Retrieved on 31 July 2014.

- ^ Половина век борба на Виктор Аќимовиќ за вистината за Македонија Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Vest.com.mk. 21 April 2007.

- ^ Francisca de Haan; Krasimira Daskalova; Anna Loutfi. Biographical Dictionary of Women's Movements and Feminisms in Central, Eastern, and South Eastern Europe: 19th and 20th Centuries. pp. 459–461.

External links[]

Media related to Kočo Racin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kočo Racin at Wikimedia Commons- Selected Poetry by Racin, in Macedonian and English

- Two poems of Racin, in Macedonian and English

- Kočo Racin Archive (in Macedonian)

- Kočo Racin Archive from MANU (in Macedonian)

- Racin's "Result", an English translation

- 1908 births

- 1943 deaths

- People from Veles, North Macedonia

- People from Kosovo Vilayet

- Yugoslav communists

- Yugoslav Partisans members

- Macedonian writers

- Serbian writers

- Socialist feminists