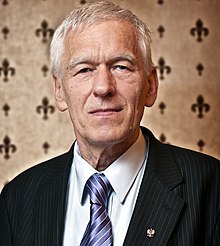

Kornel Morawiecki

Kornel Morawiecki | |

|---|---|

| |

| Senior Marshal of the Sejm | |

| In office 12 November 2015 – 12 November 2015 | |

| Chairman of Freedom and Solidarity | |

| In office 18 May 2016 – 30 September 2019 | |

| Chairman of the | |

| In office 7 July 1990 – 25 September 1993 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kornel Andrzej Morawiecki May 3, 1941 Warsaw, General Government |

| Died | September 30, 2019 (aged 78) Warsaw, Poland |

| Spouse(s) | Jadwiga Morawiecka (1st marriage) Anna Morawiecka (2nd marriage) |

| Children | 5 |

| Parents | Michał Morawiecki Jadwiga Szumańska |

| Relatives | Mateusz Morawiecki (son) |

| Alma mater | University of Wrocław |

| Signature | |

Kornel Andrzej Morawiecki (3 May 1941 – 30 September 2019) was a Polish politician, the founder and leader of Fighting Solidarity (Polish: Solidarność Walcząca), one of the splinters of the Solidarity movement in Poland during the 1980s.[1] His academic background was that of a theoretical physicist.[2] He was also a member of the 8th legislature of the Sejm,[3] of which was also the Senior Marshal on 12 November 2015. His son Mateusz Morawiecki is the Prime Minister of Poland[4] and a former chairman of Bank Zachodni WBK.

Life and career[]

Morawiecki was born in Warsaw, Poland, the son of Michał and Jadwiga (née Szumańska). He graduated from the gimnazjum of Adam Mickiewicz in 1958 in Warsaw. He finished a higher degree in physics at the University of Wrocław in 1963. He completed his doctorate under Jan Rzewuski in Quantum Field Theory in 1970. He worked as a researcher at the University of Wrocław, at first in the Institute of Physics, and later in Mathematics. After 1973, he worked at the Wrocław Polytechnic.

In 1968 he took part in student strikes and demonstrations.[5] After the repression of the student protests, together with a group of close friends he edited, printed, and distributed pamphlets which denounced the Communist government for their repressions against the protesting students.[6]

Since 1979, he became the editor of the (Lower Silesian Bulletin) together with Jan Waszkiewicz, an underground newspaper. He was a delegate to the First National Congress of NSZZ Solidarity.[2]

At the end of May 1982, together with , he founded the "Organization of Fighting Solidarity" which was a unique political opposition organization in Poland and the countries of the Soviet Bloc. It was the only group which from the beginning of its existence called for an end to communism in Poland[2] and other Soviet satellites, the establishment of sovereign governments independent from Moscow therein, the breakup of the Soviet Union and separation of the USSR republics into new nation states, and the reunification of Germany within its Potsdam-imposed borders. While eventually all these things did in fact come to pass, at the time this program was seen as quite radical and unrealistic, even in dissident circles.

However, Fighting Solidarity also rejected the use of violence to achieve its aims.[2] After the declaration of martial law in Poland in 1981, Morawiecki became one of the most wanted people in Poland.[7] In 1984, on the directive of General Czesław Kiszczak, a special team was created in the Ministry of Internal Affairs charged with observing several dozen locations in which the authorities thought he could show up.[7]

On 9 November 1987, after six years of conspiratorial activity in the underground, he was caught and arrested by the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (Secret Police) in Wrocław and was immediately transported by helicopter to Warsaw, and imprisoned in Rakowiecka Prison. Despite his capture, none of his associates, nor those who hid him during the past six years, nor the archives of the organization were captured. At the end of April, 1988 he was given the opportunity to travel to Rome for much needed medical treatment by the communist authorities (who at the time were trying to get rid of "difficult" people), while his right of return to Poland was guaranteed through mediation by the Catholic Church.[1] Three days later, he attempted to return to Poland but his passport was confiscated and he was deported from the airport in Warsaw to Vienna.[1] He managed to illegally re-enter Poland in September 1988, by pretending to be a Canadian human rights delegate.[1]

After the fall of communism in Poland, Morawiecki registered his candidacy for the post of President of Poland in 1990, but in the end was unable to collect the required 100,000 signatures.[8] During his televised election campaign he symbolically turned over a round table, a reference to the Polish Round Table Agreement which, he felt, compromised too much with the communists.[9]

For his activism in support of an independent Poland, the Polish Government in Exile under president Kazimierz Sabbat awarded him the Officer's Cross of Polonia Restituta (Order of Poland Reborn). In June 2007, on the 25th anniversary of Fighting Solidarity, he refused to accept the Grand Cross of Polonia Restituta from the President of Poland, arguing that the organization he represented deserved the highest possible state honour - the Order of the White Eagle.[10] He was also awarded the Karel Kramář Medal by the Czech Prime Minister Mirek Topolánek, for his opposition to the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.[10][11]

He was one of the candidates in the 2010 Polish presidential election, but received only 0.13% of the vote and did not make it into the second round. In the 2015 Sejm election, he was first-place candidate on the Kukiz'15 electoral list of Paweł Kukiz in the Wrocław electoral district.[12] He was involved in a Sejm scandal in April 2016, when Morawiecki left his Sejm member card in the voting device after feeling ill and exiting the debating hall, resulting in MP Małgorzata Zwiercan casting his vote for him. The political party Civic Platform notified the National Public Prosecutor's Office of this event. Following the scandal, he left Kukiz'15 and began organizing his own party along with Małgorzata Zwiercan, who had been expelled from the Parliamentary club.

Apart from his work as a politician, he also worked at the Mathematics Institute of the Wrocław University of Technology.[13]

Personal life[]

In 1959 he married Jadwiga with whom he has four children including Mateusz Morawiecki, the Prime Minister of Poland. After his divorce from Jadwiga, he married Anna with whom he had a son.[14][15] He died in 2019 from pancreatic cancer.

See also[]

- Solidarity movement

- History of Poland (1945–1989)

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sabrina P. Ramet, "Social currents in Eastern Europe", Duke University Press, 1995, pg. 98 and 190, [1], [2]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d JPRS Report, East Europe, June 4, 1990, pgs. 18-21

- ^ "Wybory do Sejmu i Senatu". Archived from the original on 2017-07-03. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ "Komitet Polityczny PiS desygnował Mateusza Morawieckiego na Premiera". Prawo i Sprawiedliwość. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Government of the Czech Government, "August 21, 2008: Premier Awarded Commemorative Medals to Ten Dissidents from 1968", 21. 8. 2008, [3]

- ^ (in Polish) Solidarność Walcząca, czyli po niepodległość bez kompromisów Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine Magazyn Obywatel nr 5 / 2005 (25)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Artur Adamski, "Czas wielkiej próby" (The Time of Great Trial), Encyclopedia Solidarnosci (Encyclopedia of Solidarity) and Gazeta Polska, June 4, 2008, [4]

- ^ Dominik Gajda, "Poland After the Round Table - The History of the Independent Poland 1989-2007", pg. 4, [5]

- ^ Kornel Morawiecki, "Dlaczego przewróciłem okrągły stolik" (Why did I overturn a round table?), Rzeczpospolita, 05-02-2009, [6]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bartłomiej Radziejowski, "Czechów powinna przepraszać Moskwa" (Moscow Should Apologize to the Czechs), Rzeczpospolita, 2008-08-23, accessed at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-07-23. Retrieved 2009-08-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Výstava 21. 8. - 26. 10. 2008: Za vaši a naši svobodu - Fotogalerie - ICV". icv.vlada.cz.

- ^ "Wybory do Sejmu RP i Senatu RP" (in Polish). Państwowa Komisja Wyborcza. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Kornel Morawiecki - english version". old.im.pwr.wroc.pl.

- ^ "Mateusz Morawiecki nowym ministrem rozwoju i wicepremierem w rządzie Beaty Szydło". 9 November 2015.

- ^ INTERIA.PL. "Morawiecki: Ma żonę, żyje z partnerką".

- 1941 births

- 2019 deaths

- Politicians from Warsaw

- Wrocław University of Science and Technology faculty

- University of Warsaw alumni

- Movement for Reconstruction of Poland politicians

- Polish anti-communists

- Polish dissidents

- Officers of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Candidates in the 2015 Polish presidential election

- Solidarity (Polish trade union) activists

- Candidates in the 2010 Polish presidential election

- Deaths from pancreatic cancer

- Deaths from cancer in Poland