Kumhar

| |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Hindi, Sindhi, Rajasthani, Haryanvi, Awadhi, Gujarati, Marathi, Nagpuri, Odia, Punjabi |

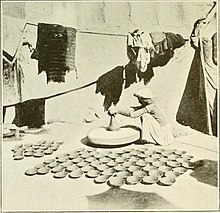

Kumhar is a caste or community in India, Nepal and Pakistan. Kumhar have historically been associated with art of pottery. [1]

Etymology

The Kumhars derive their name from the Sanskrit word Kumbhakar meaning earthen-pot maker.[2] Dravidian languages conform to the same meaning of the term Kumbhakar. The term Bhande, used to designate the Kumhar caste, also means pot. The potters of Amritsar are called Kulal or Kalal, the term used in Yajurveda to denote the potter class.[1]

Mythological origin

A section of Hindu Kumhars honorifically call themselves Prajapati after Vedic Prajapati, the Lord, who created the universe.[1]

According to a legend prevalent among Kumhars

Once Brahma divided sugarcane among his sons and each of them ate his share, but the Kumhara who was greatly absorbed in his work, forgot to eat. The piece which he had kept near his clay lump struck root and soon grew into a sugarcane plant. A few days later, when Brahma asked his sons for sugarcane, none of them could give it to him, excepting the Kumhara who offered a full plant. Brahma was pleased by the devotion of the potter to his work and awarded him the title Prajapati.[1]

There is an opinion that this is because of their traditional creative skills of pottery, they are regarded as Prajapati.[3]

History

Pottery in Indian subcontinent dates back to Mesolithic period which developed among Vindhya hunter-gatherers.[4][5] This early type of pottery, found at the site of Lahuradewa, is the oldest known pottery tradition in South Asia, dating back to 7,000-6,000 BC.[6][7][8][9]

Divisions

The potters are classified into Hindu and Muslim cultural groups.[1] Among Hindus, inclusion of artisan castes, such as potters, in the Shudra varna is indisputable. They are further divided into two groups-clean caste and unclean caste .[10]

Among the Kumhars are groups such as the Gujrati Kumhar, Kurali ke Kumhar, Lad and Telangi. They all, bear these names after different cultural linguistic zones or caste groups but are termed as one caste cluster.[11]

Distribution in India

Chamba (Himanchal)

The Kumhars of Chamba are expert in making pitchers, Surahis, vessels, grain jars, toys for entertainment and earthen lamps. Some of these pots bear paintings and designs also.[3]

Maharashtra (Marathe)

Kumhars are found in Satara, Sangli, Kolhapur, Sholapur and Pune. Their language is Marathi. They use Devnagari script for communication.[12] There are Kumbhars who do not belong to Maratha clan lives in Maharashtra and have occupation of making idols and pots.[1][12]

Madhya Pradesh

Hathretie and Chakretie (or Challakad) Kumhars are found in Madhya Pradesh. Hathretie Kumhars are called so because they traditionally moved the "chak" (potter's wheel) by hands ("hath"). Gola is a common surname among Kumhars in Madhya Pradesh.[13][clarification needed] They are categorised as a Scheduled Caste in Chhatarpur, Datia, Panna, Satna, Tikamgarh, Sidhi and Shahdol districts[14] but elsewhere in the state they are listed among Other Backward Classes.[15]

Rajasthan

In Rajasthan, Kumhars (Also known as Prajapat) have six sub-groups namely Mathera, Kumavat, Kheteri, Marwara, Timria and Mawalia. In the social hierarchy of Rajasthan, they are placed in the middle of the higher castes and the Harijans. They follow endogamy with clan exogamy.[2]

Odisha and Bengal

In Bengal Kumhars are one among the ceremonially pure castes. In Odisha they are two types (Odia Kumbhar and Jhadua Kumbhar) who provide vessels for the rice distribution to Jagannath temple.[16] They are belongs to Other Backward Classes in the state of Odisha.[17]

Uttar Pradesh and Bihar

The Kannuaja Kumhars are considered to be a decent caste in both Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Although they sometimes use the term Pandit as their Surname. The Magahiya Kumhars are treated little inferior to the Kanaujias and the Turkaha (Gadhere).[18] They belong to other backward classes.

Gujarat

Kumhars are listed among the Other Backward Classes of Gujarat, where they are listed with the following communities: Prajapati (Gujjar Prajapati, Varia Prajapati, Sorthia Prajapati), Sorathiya Prajapati.[19]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kumhar. |

- ^ a b c d e f Saraswati, Baidyanath (1979). Pottery-Making Cultures And Indian Civilization. Abhinav Publications. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-81-7017-091-4. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ a b Mandal, S. K. (1998). "Kumhar/Kumbhar". In Singh, Kumar Suresh (ed.). People of India: Rajasthan. Popular Prakashan. pp. 565–566. ISBN 978-8-17154-769-2.

- ^ a b Bhāratī, Ke. Āra (2001). Chamba Himalaya: Amazing Land, Unique Culture. Indus Publishing. p. 178. ISBN 978-8-17387-125-2.

- ^ D. Petraglia, Michael (14 March 2021). The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia (2007 ed.). Springer. p. 407. ISBN 9781402055614. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, Volume 49, Dr. A. M. Ghatage, Page 303-304

- ^ Peter Bellwood; Immanuel Ness (10 November 2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. John Wiley & Sons. p. 250. ISBN 9781118970591.

- ^ Gwen Robbins Schug; Subhash R. Walimbe (13 April 2016). A Companion to South Asia in the Past. John Wiley & Sons. p. 350. ISBN 9781119055471.

- ^ Barker, Graeme; Goucher, Candice (2015). The Cambridge World History: Volume 2, A World with Agriculture, 12,000 BCE–500 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 470. ISBN 9781316297780.

- ^ Cahill, Michael A. (2012). Paradise Rediscovered: The Roots of Civilisation. Interactive Publications. p. 104. ISBN 9781921869488.

- ^ Saraswati, Baidyanath (1979). Pottery-Making Cultures And Indian Civilization. Abhinav Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-81-7017-091-4. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Vidyarthi, Lalita Prasad (1976). Rise of Anthropology in India. Concept Publishing Company. p. 293.

- ^ a b Khan, I. A. (2004). "Kumbhar/Kumhar". In Bhanu, B. V. (ed.). People of India: Maharashtra, Part 2. Popular Prakashan. pp. 1175–1176. ISBN 978-8-17991-101-3.

- ^ "The Kumhars of Gwalior". Archived from the original on 23 March 2010.

- ^ "Part IX - Madhya Pradesh" (PDF). DSJE, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2016.

- ^ "Central List of OBCs: State : Madhya Pradesh". National Commission for Backwards Classes. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ "www.ijirssc.in" (PDF).

- ^ "www.bcmbcmw.tn.gov.in" (PDF).

- ^ Saraswati, Baidyanath (1979). Pottery-Making Cultures And Indian Civilization. Abhinav Publications. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-81-7017-091-4. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF GUJARAT" (PDF). Government of India.

- Kumhar

- Social groups of Rajasthan

- Social groups of Uttar Pradesh

- Social groups of Bihar

- Social groups of Gujarat

- Social groups of Maharashtra

- Social groups of Madhya Pradesh

- Social groups of Punjab, India

- Social groups of Haryana

- Indian castes

- Indian pottery

- Other Backward Classes

- Pot-making castes

- Social groups of Odisha