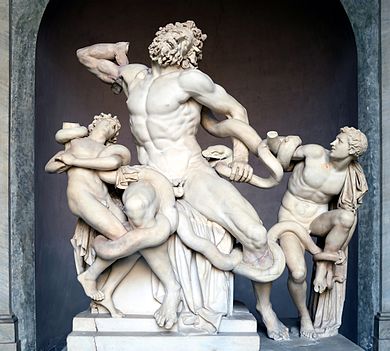

Laocoön and His Sons

| Laocoön and His Sons | |

|---|---|

| |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 208 cm × 163 cm × 112 cm (6 ft 10 in × 5 ft 4 in × 3 ft 8 in)[1] |

| Location | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

| 41°54′15″N 12°27′17″E / 41.90417°N 12.45472°E | |

The statue of Laocoön and His Sons, also called the Laocoön Group (Italian: Gruppo del Laocoonte), has been one of the most famous ancient sculptures ever since it was excavated in Rome in 1506 and placed on public display in the Vatican,[2] where it remains. It is very likely the same statue praised in the highest terms by the main Roman writer on art, Pliny the Elder.[3] The figures are near life-size and the group is a little over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in height, showing the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus being attacked by sea serpents.[1]

The group has been called "the prototypical icon of human agony" in Western art,[4] and unlike the agony often depicted in Christian art showing the Passion of Jesus and martyrs, this suffering has no redemptive power or reward.[5] The suffering is shown through the contorted expressions of the faces (Charles Darwin pointed out that Laocoön's bulging eyebrows are physiologically impossible),[6] which are matched by the struggling bodies, especially that of Laocoön himself, with every part of his body straining.[7]

Pliny attributes the work, then in the palace of Emperor Titus, to three Greek sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydorus, but does not give a date or patron. In style it is considered "one of the finest examples of the Hellenistic baroque" and certainly in the Greek tradition,[8] but it is not known whether it is an original work or a copy of an earlier sculpture, probably in bronze, or made for a Greek or Roman commission. The view that it is an original work of the 2nd century BC now has few if any supporters, although many still see it as a copy of such a work made in the early Imperial period, probably of a bronze original.[9] Others see it as probably an original work of the later period, continuing to use the Pergamene style of some two centuries earlier. In either case, it was probably commissioned for the home of a wealthy Roman, possibly of the Imperial family. Various dates have been suggested for the statue, ranging from about 200 BC to the 70s AD,[10] though "a Julio-Claudian date [between 27 BC and 68 AD] ... is now preferred".[11]

Although mostly in excellent condition for an excavated sculpture, the group is missing several parts, and analysis suggests that it was remodelled in ancient times and has undergone a number of restorations since it was excavated.[12] It is on display in the Museo Pio-Clementino, a part of the Vatican Museums.

Subject[]

The story of Laocoön, a Trojan priest, came from the Greek Epic Cycle on the Trojan Wars, though it is not mentioned by Homer. It had been the subject of a tragedy, now lost, by Sophocles and was mentioned by other Greek writers, though the events around the attack by the serpents vary considerably. The most famous account of these is now in Virgil's Aeneid (see the Aeneid quotation at the entry Laocoön), but this dates from between 29 and 19 BC, which is possibly later than the sculpture. However, some scholars see the group as a depiction of the scene as described by Virgil.[13]

In Virgil, Laocoön was a priest of Poseidon who was killed with both his sons after attempting to expose the ruse of the Trojan Horse by striking it with a spear. In Sophocles, on the other hand, he was a priest of Apollo, who should have been celibate but had married. The serpents killed only the two sons, leaving Laocoön himself alive to suffer.[14] In other versions he was killed for having had sex with his wife in the temple of Poseidon, or simply making a sacrifice in the temple with his wife present.[15] In this second group of versions, the snakes were sent by Poseidon[16] and in the first by Poseidon and Athena, or Apollo, and the deaths were interpreted by the Trojans as proof that the horse was a sacred object. The two versions have rather different morals: Laocoön was either punished for doing wrong, or for being right.[8]

The snakes are depicted as both biting and constricting, and are probably intended as venomous, as in Virgil.[17] Pietro Aretino thought so, praising the group in 1537:

...the two serpents, in attacking the three figures, produce the most striking semblances of fear, suffering and death. The youth embraced in the coils is fearful; the old man struck by the fangs is in torment; the child who has received the poison, dies.[18]

In at least one Greek telling of the story the older son is able to escape, and the composition seems to allow for that possibility.[19]

History[]

Ancient times[]

The style of the work is agreed to be that of the Hellenistic "Pergamene baroque" which arose in Greek Asia Minor around 200 BC, and whose best known undoubtedly original work is the Pergamon Altar, dated c. 180–160 BC, and now in Berlin.[20] Here the figure of Alcyoneus is shown in a pose and situation (including serpents) which is very similar to those of Laocoön, though the style is "looser and wilder in its principles" than the altar.[21]

The execution of the Laocoön is extremely fine throughout, and the composition very carefully calculated, even though it appears that the group underwent adjustments in ancient times. The two sons are rather small in scale compared to their father,[21] but this adds to the impact of the central figure. The fine white marble used is often thought to be Greek, but has not been identified by analysis.

Pliny[]

In Pliny's survey of Greek and Roman stone sculpture in his encyclopedic Natural History (XXXVI, 37), he says:

....in the case of several works of very great excellence, the number of artists that have been engaged upon them has proved a considerable obstacle to the fame of each, no individual being able to engross the whole of the credit, and it being impossible to award it in due proportion to the names of the several artists combined. Such is the case with the Laocoön, for example, in the palace of the Emperor Titus, a work that may be looked upon as preferable to any other production of the art of painting or of [bronze] statuary. It is sculptured from a single block, both the main figure as well as the children, and the serpents with their marvellous folds. This group was made in concert by three most eminent artists, Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, natives of Rhodes.[22]

It is generally accepted that this is the same work as is now in the Vatican.[23] It is now very often thought that the three Rhodians were copyists, perhaps of a bronze sculpture from Pergamon, created around 200 BC.[24][25] It is noteworthy that Pliny does not address this issue explicitly, in a way that suggests "he regards it as an original".[26] Pliny states that it was located in the palace of the emperor Titus, and it is possible that it remained in the same place until 1506 (see "Findspot" section below). He also asserts that it was carved from a single piece of marble, though the Vatican work comprises at least seven interlocking pieces.[27][28] The phrase translated above as "in concert" (de consilii sententia) is regarded by some as referring to their commission rather than the artists' method of working, giving in Nigel Spivey's translation: " [the artists] at the behest of council designed a group...", which Spivey takes to mean that the commission was by Titus, possibly even advised by Pliny among other savants.[29]

The same three artists' names, though in a different order (Athenodoros, Agesander, and Polydorus), with the names of their fathers, are inscribed on one of the sculptures at Tiberius's villa at Sperlonga (though they may predate his ownership),[30] but it seems likely that not all the three masters were the same individuals.[31] Though broadly similar in style, many aspects of the execution of the two groups are drastically different, with the Laocoon group of much higher quality and finish.[32]

Some scholars used to think that honorific inscriptions found at Lindos in Rhodes dated Agesander and Athenodoros, recorded as priests, to a period after 42 BC, making the years 42 to 20 BC the most likely date for the Laocoön group's creation.[24] However the Sperlonga inscription, which also gives the fathers of the artists, makes it clear that at least Agesander is a different individual from the priest of the same name recorded at Lindos, though very possibly related. The names may have recurred across generations, a Rhodian habit, within the context of a family workshop (which might well have included the adoption of promising young sculptors).[33] Altogether eight "signatures" (or labels) of an Athenodoros are found on sculptures or bases for them, five of these from Italy. Some, including that from Sperlonga, record his father as Agesander.[34] The whole question remains the subject of academic debate.

Renaissance[]

The group was unearthed in February 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis; informed of the fact, Pope Julius II, an enthusiastic classicist, sent for his court artists. Michelangelo was called to the site of the unearthing of the statue immediately after its discovery,[35] along with the Florentine architect Giuliano da Sangallo and his eleven-year-old son Francesco da Sangallo, later a sculptor, who wrote an account over sixty years later:[36]

The first time I was in Rome when I was very young, the pope was told about the discovery of some very beautiful statues in a vineyard near Santa Maria Maggiore. The pope ordered one of his officers to run and tell Giuliano da Sangallo to go and see them. So he set off immediately. Since Michelangelo Buonarroti was always to be found at our house, my father having summoned him and having assigned him the commission of the pope’s tomb, my father wanted him to come along, too. I joined up with my father and off we went. I climbed down to where the statues were when immediately my father said, "That is the Laocoön, which Pliny mentions". Then they dug the hole wider so that they could pull the statue out. As soon as it was visible everyone started to draw (or "started to have lunch"),[37] all the while discoursing on ancient things, chatting as well about the ones in Florence.

Julius acquired the group on March 23, giving De Fredis a job as a scribe as well as the customs revenues from one of the gates of Rome. By August the group was placed for public viewing in a niche in the wall of the brand new Belvedere Garden at the Vatican, now part of the Vatican Museums, which regard this as the start of their history. As yet it had no base, which was not added until 1511, and from various prints and drawings from the time the older son appears to have been completely detached from the rest of the group.[38]

In July 1798 the statue was taken to France in the wake of the French conquest of Italy, though the replacement parts were left in Rome. It was on display when the new Musée Central des Arts, later the Musée Napoléon, opened at the Louvre in November 1800. A competition was announced for new parts to complete the composition, but there were no entries. Some plaster sections by François Girardon, over 150 years old, were used instead. After Napoleon's final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 most (but certainly not all) the artworks plundered by the French were returned, and the Laocoön reached Rome in January 1816.[39]

Restorations[]

When the statue was discovered, Laocoön's right arm was missing, along with part of the hand of one child and the right arm of the other, and various sections of snake. The older son, on the right, was detached from the other two figures.[40] The age of the altar used as a seat by Laocoön remains uncertain.[41] Artists and connoisseurs debated how the missing parts should be interpreted. Michelangelo suggested that the missing right arms were originally bent back over the shoulder. Others, however, believed it was more appropriate to show the right arms extended outwards in a heroic gesture.[42]

According to Vasari, in about 1510 Bramante, the Pope's architect, held an informal contest among sculptors to make replacement right arms, which was judged by Raphael, and won by Jacopo Sansovino.[43] The winner, in the outstretched position, was used in copies but not attached to the original group, which remained as it was until 1532, when Giovanni Antonio Montorsoli, a pupil of Michelangelo, added his even more straight version of Laocoön's outstretched arm, which remained in place until modern times. In 1725–1727 Agostino Cornacchini added a section to the younger son's arm, and after 1816 Antonio Canova tidied up the group after their return from Paris, without being convinced by the correctness of the additions but wishing to avoid a controversy.[44]

In 1906 Ludwig Pollak, archaeologist, art dealer and director of the Museo Barracco, discovered a fragment of a marble arm in a builder's yard in Rome, close to where the group was found. Noting a stylistic similarity to the Laocoön group he presented it to the Vatican Museums: it remained in their storerooms for half a century. In 1957 the museum decided that this arm – bent, as Michelangelo had suggested – had originally belonged to this Laocoön, and replaced it. According to Paolo Liverani: "Remarkably, despite the lack of a critical section, the join between the torso and the arm was guaranteed by a drill hole on one piece which aligned perfectly with a corresponding hole on the other."[45]

In the 1980s the statue was dismantled and reassembled, again with the Pollak arm incorporated.[46] The restored portions of the children's arms and hands were removed. In the course of disassembly,[47] it was possible to observe breaks, cuttings, metal tenons, and dowel holes which suggested that in antiquity, a more compact, three-dimensional pyramidal grouping of the three figures had been used or at least contemplated. According to Seymour Howard, both the Vatican group and the Sperlonga sculptures "show a similar taste for open and flexible pictorial organization that called for pyrotechnic piercing and lent itself to changes at the site, and in new situations".[11] The more open, planographic composition along a plane, used in the restoration of the Laocoön group, has been interpreted as "apparently the result of serial reworkings by Roman Imperial as well as Renaissance and modern craftsmen". A different reconstruction was proposed by Seymour Howard, to give "a more cohesive, baroque-looking and diagonally-set pyramidal composition", by turning the older son as much as 90°, with his back to the side of the altar, and looking towards the frontal viewer rather than at his father.[48] Other suggestions have been made.[49]

Influence[]

The discovery of the Laocoön made a great impression on Italian artists and continued to influence Italian art into the Baroque period. Michelangelo is known to have been particularly impressed by the massive scale of the work and its sensuous Hellenistic aesthetic, particularly its depiction of the male figures. The influence of the Laocoön, as well as the Belvedere Torso, is evidenced in many of Michelangelo's later sculptures, such as the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave, created for the tomb of Pope Julius II. Several of the ignudi and the figure of Haman in the Sistine Chapel ceiling draw on the figures.[50] Raphael used the face of Laocoön for his Homer in his Parnassus in the Raphael Rooms, expressing blindness rather than pain.[51]

The Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli was commissioned to make a copy by the Medici Pope Leo X. Bandinelli's version, which was often copied and distributed in small bronzes, is in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, the Pope having decided it was too good to send to François I of France as originally intended.[52] A bronze casting, made for François I at Fontainebleau from a mold taken from the original under the supervision of Primaticcio, is at the Musée du Louvre. There are many copies of the statue, including a well-known one in the Grand Palace of the Knights of St. John in Rhodes. Many still show the arm in the outstretched position, but the copy in Rhodes has been corrected.

The group was rapidly depicted in prints as well as small models, and became known all over Europe. Titian appears to have had access to a good cast or reproduction from about 1520, and echoes of the figures begin to appear in his works, two of them in the Averoldi Altarpiece of 1520–1522.[53] A woodcut, probably after a drawing by Titian, parodied the sculpture by portraying three apes instead of humans. It has often been interpreted as a satire on the clumsiness of Bandinelli's copy, or as a commentary on debates of the time around the similarities between human and ape anatomy.[54] It has also been suggested that this woodcut was one of a number of Renaissance images that were made to reflect contemporary doubts as to the authenticity of the Laocoön Group, the 'aping' of the statue referring to the incorrect pose of the Trojan priest who was depicted in ancient art in the traditional sacrificial pose, with his leg raised to subdue the bull.[55] Over 15 drawings of the group made by Rubens in Rome have survived, and the influence of the figures can be seen in many of his major works, including his Descent from the Cross in Antwerp Cathedral.[56]

The original was seized and taken to Paris by Napoleon Bonaparte after his conquest of Italy in 1799, and installed in a place of honour in the Musée Napoléon at the Louvre. Following the fall of Napoleon, it was returned by the Allies to the Vatican in 1816.

Laocoön as an ideal of art[]

Pliny's description of Laocoön as "a work to be preferred to all that the arts of painting and sculpture have produced"[57] has led to a tradition which debates this claim that the sculpture is the greatest of all artworks. Johann Joachim Winkelmann (1717–1768) wrote about the paradox of admiring beauty while seeing a scene of death and failure.[58] The most influential contribution to the debate, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's essay Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, examines the differences between visual and literary art by comparing the sculpture with Virgil's verse. He argues that the artists could not realistically depict the physical suffering of the victims, as this would be too painful. Instead, they had to express suffering while retaining beauty.[59]

Johann Goethe said the following in his essay, Upon the Laocoon "A true work of art, like a work of nature, never ceases to open boundlessly before the mind. We examine, – we are impressed with it, – it produces its effect; but it can never be all comprehended, still less can its essence, its value, be expressed in words.[60]

The most unusual intervention in the debate, William Blake's annotated print Laocoön, surrounds the image with graffiti-like commentary in several languages, written in multiple directions. Blake presents the sculpture as a mediocre copy of a lost Israelite original, describing it as "Jehovah & his two Sons Satan & Adam as they were copied from the Cherubim Of Solomons Temple by three Rhodians & applied to Natural Fact or History of Ilium".[61] This reflects Blake's theory that the imitation of ancient Greek and Roman art was destructive to the creative imagination, and that Classical sculpture represented a banal naturalism in contrast to Judeo-Christian spiritual art.

The central figure of Laocoön served as loose inspiration for the Indian in Horatio Greenough's The Rescue (1837–1850) which stood before the east facade of the United States Capitol for over 100 years.[62]

Near the end of Charles Dickens' 1843 novella, A Christmas Carol, Ebenezer Scrooge self-describes "making a perfect Laocoön of himself with his stockings" in his hurry to dress on Christmas morning.

John Ruskin disliked the sculpture and compared its "disgusting convulsions" unfavourably with work by Michelangelo, whose fresco of The Brazen Serpent, on a corner pendentive of the Sistine Chapel, also involves figures struggling with snakes – the fiery serpents of the Book of Numbers.[63] He invited contrast between the "meagre lines and contemptible tortures of the Laocoon" and the "awfulness and quietness" of Michelangelo, saying "the slaughter of the Dardan priest" was "entirely wanting" in sublimity.[63] Furthermore, he attacked the composition on naturalistic grounds, contrasting the carefully studied human anatomy of the restored figures with the unconvincing portrayal of the snakes:[63]

For whatever knowledge of the human frame there may be in the Laocoön, there is certainly none of the habits of serpents. The fixing of the snake's head in the side of the principal figure is as false to nature, as it is poor in composition of line. A large serpent never wants to bite, it wants to hold, it seizes therefore always where it can hold best, by the extremities, or throat, it seizes once and forever, and that before it coils, following up the seizure with the twist of its body round the victim, as invisibly swift as the twist of a whip lash round any hard object it may strike, and then it holds fast, never moving the jaws or the body, if its prey has any power of struggling left, it throws round another coil, without quitting the hold with the jaws; if Laocoön had had to do with real serpents, instead of pieces of tape with heads to them, he would have been held still, and not allowed to throw his arms or legs about.

— John Ruskin, Modern Painters, 1856, vol. 3, ch. VII.

In 1910 the critic Irving Babbit used the title The New Laokoon: An Essay on the Confusion of the Arts for an essay on contemporary culture at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1940 Clement Greenberg adapted the concept for his own essay entitled Towards a Newer Laocoön in which he argued that abstract art now provided an ideal for artists to measure their work against. A 2007 exhibition[64] at the Henry Moore Institute in turn copied this title while exhibiting work by modern artists influenced by the sculpture.

Findspot[]

The location where the buried statue was found in 1506 was always known to be "in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis" on the Oppian Hill (the southern spur of the Esquiline Hill), as noted in the document recording the sale of the group to the Pope. But over time, knowledge of the site's precise location was lost, beyond "vague" statements such as Sangallo's "near Santa Maria Maggiore" (see above) or it being "near the site of the Domus Aurea" (the palace of the Emperor Nero); in modern terms near the Colosseum.[65] An inscribed plaque of 1529 in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli records the burial of De Fredis and his son there, covering his finding of the group but giving no occupation. Research published in 2010 has recovered two documents in the municipal archives (badly indexed, and so missed by earlier researchers), which have established a much more precise location for the find: slightly to the east of the southern end of the Sette Sale, the ruined cistern for the successive imperial baths at the base of the hill by the Colosseum.[66]

The first document records De Fredis' purchase of a vineyard of about 1.5 hectares from a convent for 135 ducats on 14 November 1504, exactly 14 months before the finding of the statue. The second document, from 1527, makes it clear that there is now a house on the property, and clarifies the location; by then De Fredis was dead and his widow rented out the house. The house appears on a map of 1748,[67] and still survives as a substantial building of three storeys, as of 2014 in the courtyard of a convent. The area remained mainly agricultural until the 19th century, but is now entirely built up. It is speculated that De Fredis began building the house soon after his purchase, and as the group was reported to have been found some four metres below ground, at a depth unlikely to be reached by normal vineyard-digging operations, it seems likely that it was discovered when digging the foundations for the house, or possibly a well for it.[66]

The findspot was inside and very close to the Servian Wall, which was still maintained in the 1st century AD (possibly converted to an aqueduct), though no longer the city boundary, as building had spread well beyond it. The spot was within the Gardens of Maecenas, founded by Gaius Maecenas the ally of Augustus and patron of the arts. He bequeathed the gardens to Augustus in 8 BC, and Tiberius lived there after he returned to Rome as heir to Augustus in 2 AD. Pliny said the Laocoön was in his time at the palace of Titus (qui est in Titi imperatoris domo), then heir to his father Vespasian,[68] but the location of Titus's residence remains unknown; the imperial estate of the Gardens of Maecenas may be a plausible candidate. If the Laocoön group was already in the location of the later findspot by the time Pliny saw it, it might have arrived there under Maecenas or any of the emperors.[66] The extent of the grounds of Nero's Domus Aurea is now unclear, but they do not appear to have extended so far north or east, though the newly rediscovered findspot-location is not very far beyond them.[69]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Digital Sculpture Project: Laocoön, "Catalogue Entry: Laocoon Group"

- ^ Beard, 209

- ^ The Capitoline Wolf was until recently thought to be the same statue praised by Pliny, but recent tests suggest it is medieval.

- ^ Spivey, 25

- ^ Spivey, 28–29

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. New York: D. Appleton & Company. p. 183. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ Spivey, 25 (Darwin), 121–122

- ^ Jump up to: a b Boardman, 199

- ^ Clark, 219–221 was an early proponent of this view; see also Barkan, caption opp. p 1, Janson etc

- ^ Boardman, 199 says "about 200 BC"; Spivey, 26, 36, feels it may have been commissioned by Titus.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Howard, 422

- ^ Howard, throughout; "Chronology", and several discussions in the other sources

- ^ Boardman, 199, also Sperlonga und Vergil by Roland Hampe; but see Smith, 109 for the opposite view.

- ^ Smith, 109

- ^ Stewart, 85, this last in the commentary on Virgil of Maurus Servius Honoratus, citing Euphorion of Chalcis

- ^ William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Taylor and Walton, 1846, p. 776

- ^ The Greeks were familiar with constricting snakes, and the small boa Eryx jaculus is still native to Greece. But the danger to Ancient Greeks from venomous snakes was far greater

- ^ Farinella, 16

- ^ Stewart, 78

- ^ Boardman, 164–166, 197–199; Clark, 216–219; Cook, 153

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cook, 153

- ^ English text at Tufts, Book 36, Ch 4, but usually cited as 36:37, e.g. by Spivey, 26. Latin text: "...nec deinde multo plurium fama est, quorundam claritati in operibus eximiis obstante numero artificum, quoniam nec unus occupat gloriam nec plures pariter nuncupari possunt, sicut in laocoonte, qui est in titi imperatoris domo, opus omnibus et picturae et statuariae artis praeferendum. ex uno lapide eum ac liberos draconumque mirabiles nexus de consilii sententia fecere summi artifices Hagesander et Polydorus et Athenodorus rhodii." Naturalis Historia. Pliny the Elder. Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff. Lipsiae. Teubner. 1906, as 36:11, at Tufts. The word statuariae used by Pliny means bronze statues as opposed to stone, as pointed out by Bernard Andreae and others. See Isager, 171

- ^ As Beard, 210, a sceptic, complains; see "Chronology" at January 1506 for dissidents

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stewart, Andrew W. (1996), "Hagesander, Athanodorus and Polydorus", in Hornblower, Simon, Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Boardman, 199; Smith, 109–110

- ^ Isager, 173

- ^ Howard 417–418 and figure 1 has the fullest account used of the complicated situation here; with the damages and after the various restorations he lists 14 parts (417, note 4) when the group was last dismantled. See also Richard Brilliant, My Laocoön – alternative claims in the interpretation of artworks, University of California Press, 2000, p. 29

- ^ Rose, Herbert Jennings (1996), "Laocoön", in Hornblower, Simon (ed.), Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ^ Spivey, 26; see also Isager, 173, who translates it "by decision of the [imperial] council".

- ^ Rice, 239, with photo on 238

- ^ See Rice or Agesander

- ^ Herrmann, 277

- ^ Rice, 235–236

- ^ Rice, 239–242

- ^ In 2005 Lynn Catterson argued that the sculpture was a forgery created by Michelangelo, in Catterson, Lynn, "Michelangelo's 'Laocoön?'" Artibus et historiae. 52 2005: 29. Richard Brilliant, author of My Laocoön, described Catterson's claims as "noncredible on any count". See An Ancient Masterpiece Or a Master's Forgery?, New York Times, April 18, 2005

- ^ Barkan, 1–4, with English text; Chronology has the Italian, at 1567, the date of the letter.

- ^ Ambiguous due to a quirk of Tuscan Italian, "everyone started to eat lunch" ci tornammo a desinare – see Barkan lecture notes PDF Archived 2012-04-18 at the Wayback Machine for 2011 Jerome Lectures, University of Chicago, “Unswept Floor: Food Culture and High Culture, Antiquity and Renaissance”, Lecture 1, start: "It’s a piece of sixteenth-century spelling, and I (along with many other commentators – if I was wrong, I wasn’t wrong alone) – understood it as disegnare, that is, to draw ...[rather than] digiunare – in other words, to eat lunch." Farinelli, 16, has "And having seen it we went back to dinner, talking ..."

- ^ Chronology, 1504–1510

- ^ Chronology, 1798–1816

- ^ Howard, 417–420

- ^ Howard, 418–419, 422

- ^ Barkan, 7–11

- ^ Barkan, 7–10

- ^ Chronology; Barkan, 9–11

- ^ Liverani, Paolo, Digital Sculpture Project, "Catalogue"; Chronology, 1957

- ^ See Beard, 210, who is highly sceptical of the identification, noting that ‘the new arm does not directly join with the father's broken shoulder (a wedge of plaster has had to be inserted); it appears to be on a smaller scale and in a slightly differently coloured marble’. On the wedge, Barkan, 11 notes that in the restoration of c. 1540 "the original shoulder was severely sliced back" to fit the new section.

- ^ See figures in Howard for photos and diagram of the dis-assembled pieces

- ^ Howard, 422 and 417 quoted in turn. See also "Chronology" at 1959

- ^ "Chronology" at 1968–70

- ^ Barkan, 13–16, and on the Torso, 197–201; Spivey, 121–123; Clark, 236–237

- ^ Roger Jones and Nicholas Penny, Raphael, p. 74, Yale, 1983, ISBN 0-300-03061-4

- ^ Barkan, 10

- ^ Barkan, 11–18; Spivey, 125

- ^ Barkan, 13–16; H. W. Janson, "Titian's Laocoon Caricature and the Vesalian-Galenist Controversy", The Art Bulletin, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Mar., 1946), pp. 49–53; Clark, 390–391 rejects Janson's theory as to the meaning.

- ^ Jelbert, Rebecca: "Aping the Masters?: Michelangelo and the Laocoön Group." Journal of Art Crime, issue 22 (Fall/ Winter 2019), pp. 3–16.

- ^ Spivey, 125–127

- ^ Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2001.08.34, review of Richard Brilliant, My Laocoön: Alternative Claims.

- ^ Gustafson, Susan, Laocoon's Body and the Aesthetics of Pain: Winckelmann, Lessing, Herder, Moritz and Goethe by Simon Richter, South Atlantic Review, Vol. 58, No. 4 (Nov., 1993), pp. 145–147, JSTOR 3201020

- ^ "Laocoon and the expression of pain" Archived 2013-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, William Schupbach, Wellcome Trust

- ^ Upon The Laocoon By Johann Goethe from Essays on Art, translated by Sameul Gray Ward (1862) p. 26

- ^ Blake's comments

- ^ The Rescue by Greenough

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ruskin, John (1872). Modern Painters. 3. New York: J. Wiley. pp. 68–69.

- ^ Towards a New Laocoon, Henry Moore Institute

- ^ Volpe and Parisi; Beard, 211 complains of vagueness

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Volpe and Parisi

- ^ Volpe and Parisi; the map is Giambattista Nolli's Nuova Pianta di Roma, section image here, the house shown with a zig-zag plan to the top left of the section.

- ^ Volpe and Parisi; the text probably reflects tidying by Pliny the Younger, as his father died (25 August 79) at Pompeii only two months after Vespasian died (23 June 79) and Titus became Imperator rather than Caesar, his title as heir.

- ^ Warden, 275, approximate map of the grounds is fig. 3

References[]

- Barkan, Leonard, Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture, 1999, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-08911-2, 978-0-300-08911-0

- Beard, Mary, Times Literary Supplement, "Arms and the Man: The restoration and reinvention of classical sculpture", 2 February 2001, subscription required, reprinted in Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures and Innovations, 2013 EBL ebooks online, Profile Books, ISBN 1-84765-888-1, 978-1-84765-888-3Google Books

- Boardman, John ed., The Oxford History of Classical Art, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0-19-814386-9

- "Chronology": Frischer, Bernard, Digital Sculpture Project: Laocoon, "An Annotated Chronology of the “Laocoon” Statue Group", 2009

- Clark, Kenneth, The Nude, A Study in Ideal Form, orig. 1949, various edns, page refs from Pelican edn of 1960

- Cook, R.M., Greek Art, Penguin, 1986 (reprint of 1972), ISBN 0-14-021866-1

- Farinella, Vincenzo, Vatican Museums, Classical Art, 1985, Scala

- Haskell, Francis, and Penny, Nicholas, 1981. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (Yale University Press), cat. no. 52, pp. 243–47

- Herrmann, Ariel, review of Sperlonga und Vergil by Roland Hampe, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 56, No. 2, Medieval Issue (Jun., 1974), pp. 275–277, JSTOR 3049235

- Howard, Seymour, "Laocoon Rerestored", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 93, No. 3 (Jul., 1989), pp. 417–422, JSTOR 505589

- Isager, Jacob, Pliny on Art and Society: The Elder Pliny's Chapters On The History Of Art, 2013, Routledge, ISBN 1-135-08580-3, 978-1-135-08580-3, Google Books

- Rice, E. E., "Prosopographika Rhodiaka", The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. 81, (1986), pp. 209–250, JSTOR 30102899

- Spivey, Nigel (2001), Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23022-1, 978-0-520-23022-4

- Smith, R.R.R., Hellenistic Sculpture, a handbook, Thames & Hudson, 1991, ISBN 0500202494

- Stewart, A., "To Entertain an Emperor: Sperlonga, Laokoon and Tiberius at the Dinner-Table", The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 67, (1977), pp. 76–90, JSTOR 299920

- "Volpe and Parisi": Digital Sculpture Project: Laocoon. "Laocoon: The Last Enigma", translation by Bernard Frischer of Volpe, Rita and Parisi, Antonella, "Laocoonte. L'ultimo engima," in Archeo 299, January 2010, pp. 26–39

- Warden, P. Gregory, "The Domus Aurea Reconsidered", Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Dec., 1981), pp. 271–278, doi:10.2307/989644, JSTOR 989644

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laocoon group. |

| External video | |

|---|---|

- University of Virginia's Digital Sculpture Project 3D models, bibliography, annotated chronology of the Laocoon

- Laocoon photos

- Laocoon and his Sons in the Census database

- FlickR group "Responses To Laocoön", a collection of art inspired by the Laocoön group

- Lessing's Laocoon etext on books.google.com

- Loh, Maria H. (2011). "Outscreaming the Laocoön: Sensation, Special Affects, and the Moving Image". Oxford Art Journal. 34 (3): 393–414. doi:10.1093/oxartj/kcr039. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Laocoonte: variazioni sul mito, con una Galleria delle fonti letterarie e iconografiche su Laocoonte, a cura del Centro studi classicA, "La Rivista di Engramma" n. 50, luglio/settembre 2006 (in Italian)

- Nota sul ciclo di Sperlonga e sulle relazioni con il Laoocoonte Vaticano, a cura del Centro studi classicA, "La Rivista di Engramma" n. 50. luglio/settembre 2006 (in Italian)

- Nota sulle interpretazioni del passo di Plinio, Nat. Hist. XXXVI, 37, a cura del Centro studi classicA, "La Rivista di Engramma" n. 50. luglio/settembre 2006 (in Italian)

- Scheda cronologica dei restauri del Laocoonte, a cura di Marco Gazzola, "La Rivista di Engramma" n. 50, luglio/settembre 2006 (in Italian)

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

Laocoön by William Blake, with the texts transcribed

- 1st-century BC sculptures

- 1506 archaeological discoveries

- Antiquities acquired by Napoleon

- Hellenistic sculpture

- Roman copies of Greek sculptures

- Sculptures of the Vatican Museums

- Tourist attractions in Rome

- Archaeological discoveries in Italy

- Hellenistic-style Roman sculptures

- Nude sculptures

- Snakes in art