Servian Wall

| Servian Wall | |

|---|---|

| Rome, Italy | |

A preserved section of Servian Wall next to Termini railway station. | |

A map of Rome showing the seven Hills of Rome (pink), the Servian Wall (blue) and its gates. The Aurelian Walls (red) were constructed in the 3rd century AD. | |

| Type | Defensive wall |

| Height | Up to 10 metres (33 ft) |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | Open to public. |

| Condition | Ruinous. Fragmentary remains |

| Site history | |

| Built | 4th century BC (Livy dates grotta oscura sections from 378 BC) |

| Materials | Tuff |

| Events | Second Punic War |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Romans |

The Servian Wall (Latin: Murus Servii Tullii; Italian: Mura Serviane) was an ancient Roman defensive barrier constructed around the city of Rome in the early 4th century BC. The wall was built of volcanic tuff and was up to 10 m (33 ft) in height in places, 3.6 m (12 ft) wide at its base, 11 km (6.8 mi) long,[1] and is believed to have had 16 main gates, of which only one or two have survived, and enclosed a total area of 246 hectares (610 acres). In the 3rd century AD it was superseded by the construction of the larger Aurelian Walls as the city of Rome grew beyond the boundary of the Servian Wall.[2]

History[]

The wall is named after the sixth Roman King, Servius Tullius. The literary tradition stating that there was some type of defensive wall or earthen works that encircled the city of Rome dating to the 6th century BC has been found to be false.[3] The main extent of the Servian Wall was built in the early 4th century, during what is known as the Roman Republic.

Construction[]

The Servian Wall was originally built from large blocks of Cappellaccio tuff (a volcanic rock made from ash and rock fragments that are ejected during a volcanic eruption) that was quarried from Alban Hills volcanic complex.[4] This initial wall of Cappellaccio tuff was partially damaged and in need of restoration by the late 390s (either because of rapid disintegration or damage sustained after the Sack of Rome in 390 BC).[5] These reparations were done using the superior Grotta Oscura tuff which had become available after the Romans had defeated Veii in the 390s.[6] This tuff was quarried by the vanquished Veientines.[7] In addition to the tuff blocks, some sections of the structure incorporated a deep fossa, or a ditch, in front of the wall, as a means to effectively heighten the wall. This second iteration of the wall containing Grotta Oscura tuff is dated by Livy to have been completed in 378 BC.[8]

Along part of the topographically weaker Northern perimeter was an agger, a defensive ramp of earth that was built up along the inside of the Servian Wall. This effectively thickened the wall and also gave the defenders of Rome a base to stand while repelling an attack. The wall was also outfitted with defensive war engines, including catapults.[9]

Usage[]

The Servian Wall was maintained through the end of the Late Republic and into the Roman Empire. By this time, Rome had already begun to outgrow the original boundaries of the Servian Wall.

The Servian Wall became unnecessary as Rome became well protected by the ever-expanding strength of the field armies of the Republic and of the later Empire. As the city continued to grow and prosper, Rome was essentially unwalled for the first three centuries of the Empire. Expanding domestic structures simply incorporated existing wall sections into their foundations, an example of which survives in the Auditorium of Maecenas.[10] When German tribes made further incursions along the Roman frontier in the 3rd century AD, Emperor Aurelian had the larger Aurelian Walls built to protect the city of Rome.[11]

Present day[]

Several sections of the Servian Wall are still visible in various locations around the city of Rome. The largest section is preserved outside the Termini Station, the main railway station in Rome – including a section in a McDonald's dining area at the station. Another notable section on the Aventine Hill incorporates an arch that was supposedly for a defensive catapult from the late Republic.[12]

Gates along the Servian Wall[]

The following lists the gates that are believed to have been built, clockwise from the westernmost. (Many of these are inferred only from writings, with no known remains.)

- – this gate was where the via Aurelia entered Rome after crossing the Tiber River.

- Porta Carmentalis – the western end of the Capitoline.

- Porta Fontinalis – led from the northern end of the Capitoline into the Campus Martius along the via Lata.

- – on the Quirinal.

- – on the Quirinal.

- – on the Quirinal.

- Porta Collina – the northernmost gate, on the Quirinal, leading to the via Salaria. Hannibal camped his army within sight of this gate when he considered besieging Rome in 211 BC. This section was fortified additionally with the agger.

- – on the Viminal. This is near the large section still visible outside Termini Station.

- Porta Esquilina – this gate on the Esquiline is still visible, and incorporates the later arch of the emperor Gallienus. It led to the via Labicana, via Praenestina and via Tiburtina.

- Porta Querquetulana – this led to the .

- Porta Caelimontana – this gate is perhaps preserved in the Arch of Dolabella and Silanus, which was the reconstruction of an existing gate in 10 AD by the consuls Dolabella and Silanus.

- Porta Capena – this was the gate through which the via Appia left Rome to southern Italy after separating from the via Latina.

- – this gate on the Aventine led to the via Ardeatina.

- – headed south along the Tiber River along the via Ostiensis. Near here, on the modern viale Aventino, may be found a section of the wall incorporating an arch for a catapult.

- – also joined up with the via Ostiensis.

- Porta Trigemina – this triple gate near the Forum Boarium also led to the via Ostiensis.

Gallery[]

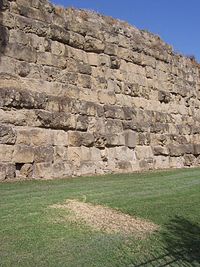

The Servian Wall at Via di Sant Anselmo

in the

Esquiline, incorporated in the Auditorium of Maecenas

in the via Salandra

at Largo Magnanapoli

in Santa Sabina crypt

in Termini station

See also[]

- Museum of the Walls, Rome

References[]

- ^ Fields, Nic; Peter Dennis 10 Mar 2008 The Walls of Rome Osprey Publishing ISBN 978-1-84603-198-4 p. 10.

- ^ Becker, J. "Places: 103808101 (Murus Servii Tullii)". Pleiades. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Carter, Jesse Benedict (1909). The evolution of the city of Rome from its origin to the Gallic catastrophe. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. p. 10.

- ^ Panei, Liliana. "The tuffs of the "Servian Wall"". Archeo-Sciences.

- ^ Le Glay, Marcel. (2009). A history of Rome. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8327-7. OCLC 760889060.

- ^ Le Glay, Marcel. (2009). A history of Rome. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8327-7. OCLC 760889060.

- ^ Forythe, Gary (2005). A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War. University of California.

- ^ Le Glay, Marcel. (2009). A history of Rome. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8327-7. OCLC 760889060.

- ^ "Notes on the Servian Wall". American Journal of Archaeology.

- ^ Kontokosta, Anne (January 2019). "Building the Thermae Agrippae: Private Life, Public Space, and the Politics of Bathing in Early Imperial Rome". American Journal of Archaeology. 123 (1): 45–77.

- ^ Watson, pp. 51–54, 217.

- ^ "Notes on the Servian Wall", American Journal of Archaeology, The University of Chicago, vol. 22, no. 2

Bibliography[]

- Bernard, Seth G. “CONTINUING THE DEBATE ON ROME'S EARLIEST CIRCUIT WALLS.” Papers of the British School at Rome 80 (2012): 1–44. doi:10.1017/S0068246212000037.

- Carandini, A., P. Carafa, Italy, and Università degli studi di Roma “La Sapienza.,” eds. 2012. Atlante di Roma antica: biografia e ritratti della città. Milano: Electa.

- Carter, Jesse Benedict. "The Evolution of the City of Rome from Its Origin to the Gallic Catastrophe." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 48, no. 192 (1909): 136. www.jstor.org/stable/984151

- Cifani, G. (1998) La documentazione archeologica delle mura arcaiche a Roma. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 105: 359–89.

- Cifani, Gabriele. "THE FORTIFICATIONS OF ARCHAIC ROME: SOCIAL AND POLITICAL SIGNIFICANCE." In Focus on Fortifications: New Research on Fortifications in the Ancient Mediterranean and the Near East, edited by Frederiksen Rune, Müth Silke, Schneider Peter I., and Schnelle Mike, 82–93. Oxford; Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2016. Accessed June 10, 2021. doi:10.2307/j.ctvh1dv3d.12.

- Claridge, Amanda. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford UP, 2010. Oxford Archaeological Guides

- Coarelli, Filippo (1989). Guida Archeologica di Roma. Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Milano.

- Forsythe, Gary. 2005. A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Holleran, C., and A. Claridge, eds. 2018. A companion to the city of Rome. Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Merrill, Elmer Truesdell. "The City of Servius and the Pomerium." Classical Philology 4, no. 4 (1909): 420–32. www.jstor.org/stable/262369

- Showerman, Grant. 1969. Rome and the Romans: A Survey and Interpretation. New York: Cooper Square

- Watson, Alaric (1999). Aurelian and the Third Century. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07248-4.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Servian Wall. |

- Servian Wall entry on the Lacus Curtius website

- Lacus Curtius page including gates in the Servian Wall

- Map showing the "Servian" wall based on new research results

Coordinates: 41°54′06″N 12°30′06″E / 41.90167°N 12.50167°E

- Buildings and structures completed in the 4th century BC

- Tourist attractions in Rome

- Walls of Rome

- 4th-century BC establishments in Italy

- Roman walls in Italy