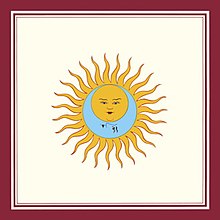

Larks' Tongues in Aspic

| Larks' Tongues in Aspic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 23 March 1973 | |||

| Recorded | January and February 1973 | |||

| Studio | Command, London | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 46:36 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | King Crimson | |||

| King Crimson chronology | ||||

| ||||

| King Crimson studio chronology | ||||

| ||||

Larks' Tongues in Aspic is the fifth studio album by the English progressive rock group King Crimson, released on 23 March 1973 through Island Records in the UK and Atlantic Records in the United States and Canada. This album is the debut of King Crimson's third incarnation, featuring co-founder and guitarist Robert Fripp along with four new members: bass guitarist and vocalist John Wetton, violinist and keyboardist David Cross, percussionist Jamie Muir, and drummer Bill Bruford. It is a key album in the band's evolution, drawing on Eastern European classical music and European free improvisation as central influences.

Background[]

At the end of the tour to promote King Crimson's previous album, Islands, Fripp had parted company with the three other members of the band (Mel Collins, Boz Burrell and Ian Wallace). Collins has stated that he was asked to stay on with the new lineup of the band, but that he decided not to continue.[1] The previous year had also seen the ousting of the band's lyricist and artistic co-director Peter Sinfield. Fripp had cited a developing musical (and sometimes personal) incompatibility with the other members, and was now writing starker music drawing less on familiar American influences and more on influences such as Béla Bartók and free improvisation.

In order to pursue these new (for King Crimson) ideas, Fripp first recruited bass guitarist/singer John Wetton (a longstanding friend of the band who had lobbied to join at least once before but had become a member of Family in the meantime). The second recruit was Jamie Muir, an experimental free-improvising percussionist who had previously been performing in the Music Improvisation Company with Derek Bailey and Evan Parker, as well as in Sunship (with Alan Gowen and Allan Holdsworth) and Boris (with Don Weller and Jimmy Roche, both later of jazz-rock band Major Surgery).

On drums (and to be paired with Muir) Fripp recruited Yes drummer Bill Bruford. Another longstanding King Crimson admirer, Bruford felt that he had done all he could with Yes at that point, and was keen to leave the band before they embarked on their Close to the Edge tour, believing that the jazz – and experimentation-oriented King Crimson would be a more expansive outlet for his musical ideas. The final member of the new band was David Cross, a violinist, keyboardist and occasional flute player.

Production[]

Larks' Tongues in Aspic showed several significant changes in King Crimson's sound. Having previously relied on saxophone and flute as significant melodic and textural instruments, the band had replaced them with a single violin. Muir's percussion rig featured exotic, eccentric instrumentation including chimes, bells, thumb pianos, a musical saw, shakers, rattles, found objects (such as sheet metal, toys and baking trays), plus miscellaneous drums and chains. The Mellotron (a staple part of King Crimson's instrumentation since their debut album) was retained for this new phase and was played by Fripp and Cross, both of whom also played electric piano. The instrumental pieces on this album have strong jazz fusion and European free-improvisation influences, and some aggressively hard-hitting portions verging on heavy metal.[2][3]

The band's multi-instrumentalism initially extended to Wetton and Muir playing (respectively) violin and trombone on occasion at early gigs. Wetton and Cross contributed additional piano and flute respectively to the album sessions. Larks' Tongues in Aspic is the only studio album with this particular lineup, since Muir left the group in February 1973, shortly after the album was completed and before they could embark for touring.

"Easy Money" was composed piecemeal, with Fripp writing the verse and Wetton later adding the chorus part.[4]

The album spawned the concert staple "Exiles", whose Mellotron introduction had been adapted from an instrumental piece called "Mantra" the band's original line up performed throughout 1969. At that time, as well as in late 1972, the melody was played by Fripp on guitar. In addition, a section of "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part One" was reworked from a piece entitled "A Peacemaking Stint Unrolls", which was recorded by the Islands-era band and finally released in 2010 as a bonus track on that album's 40th anniversary edition.

Release and reissues[]

The album peaked at number 20 on the UK charts and at number 61 in the U.S.[5] In 2012 Larks' Tongues in Aspic was issued as part of the King Crimson 40th Anniversary Series, including the release of an expansive box set subtitled "The Complete Recordings". This CD, DVD-A and Blu-ray set includes every available recording of the short-lived 5-man line-up, through live performances and studio sessions.

Reception and legacy[]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| All About Jazz | |

| AllMusic | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B–[8] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| The Great Rock Discography | 8/10[10] |

| Mojo | |

| MusicHound | |

| Record Collector | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

In his contemporary review, Alan Niester of Rolling Stone summarized the album saying "You can't dance to it, can't keep a beat to it, and it doesn't even make good background music for washing the dishes" and recommended listeners to "approach it with a completely open mind." He described the songs on the album saying that they were "a total study in contrasts, especially in moods and tempos—blazing and electric one moment, soft and intricate the next." While not fully appreciative of the music on the record, he complimented the violin playing as "tasteful [...] in the best classical tradition."[15]

Bill Martin wrote in 1998, "[f]or sheer formal inventiveness, the most important progressive rock record of 1973 was... Larks' Tongues in Aspic", adding that listening to this album and Yes's Close to the Edge will demonstrate "what progressive rock is all about".[16]

AllMusic's retrospective review was resoundingly positive, marking every aspect of the band's transition from a jazz-influenced vein to a more experimental one as a complete success. It deemed John Wetton "the group's strongest singer/bassist since Greg Lake's departure," and gave special praise to the remastered edition.[6]

Robert Christgau's retrospective review gave a more ambivalent view, saying of the band's instrumental work, "not only doesn't it cook, which figures, it doesn't quite jell either."[8]

In the Q & Mojo Classic Special Edition Pink Floyd & The Story of Prog Rock, the album came number 22 in its list of "40 Cosmic Rock Albums".[17]

The album is featured in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[18]

The progressive metal bands Dream Theater and Murmur[19] both covered "Larks' Tongues in Aspic Pt. II". The cover is featured on the special edition of Dream Theater's album Black Clouds & Silver Linings.

Track listing[]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part One" | David Cross, Robert Fripp, John Wetton, Bill Bruford, Jamie Muir | 13:36 |

| 2. | "Book of Saturday" | Fripp, Wetton, Richard Palmer-James | 2:53 |

| 3. | "Exiles" | Cross, Fripp, Palmer-James | 7:40 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Easy Money" | Fripp, Wetton, Palmer-James | 7:54 |

| 2. | "The Talking Drum" | Cross, Fripp, Wetton, Bruford, Muir | 7:26 |

| 3. | "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part Two" | Fripp | 7:07 |

Personnel[]

- King Crimson

- Robert Fripp – electric and acoustic guitars, Mellotron, Hohner pianet, devices

- John Wetton – bass, vocals, piano on "Exiles"

- Bill Bruford – drums, timbales, cowbell, wood block

- David Cross – violin, viola, Mellotron, Hohner pianet, flute on "Exiles"[20]

- Jamie Muir – percussion, drums, "allsorts" (assorted found items and sundry instruments)

- Additional personnel

- Richard Palmer-James – lyrics

- Nick Ryan – engineering

- Tantra Designs – cover design

Charts[]

| Year | Chart | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Billboard 200 | 61[21] |

References[]

- ^ "Mel Collins on Robert Fripp...and the return of King Crimson". HeraldScotland.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Heavy Metal, 2003 Barnes & Noble Books

- ^ Bradley Smith. The Billboard Guide to Progressive Music, 1997, Billboard Books, p. 119

- ^ Curtiss, Ron; Weiner, Aaron (3 June 2016). "John Wetton (King Crimson, U.K., Asia): The Complete Boffomundo Interview". YouTube. Retrieved 3 March 2019. Event occurs at 7:02-7:15.

- ^ Hoffmann 2004, p. 1144.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eder, Bruce (2011). "Larks' Tongues in Aspic - King Crimson | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ John Kelman (22 October 2012). "King Crimson: Larks' Tongues In Aspic (40th Anniversary Series Box)". All About Jazz. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: K". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved 28 February 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ Martin C. Strong (1998). The Great Rock Discography (1st ed.). Canongate Books. ISBN 978-0-86241-827-4.

- ^ Mike Barnes. "The Crown Jewels". Mojo. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Gary Graff, ed. (1996). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide (1st ed.). London: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-0-7876-1037-1.

- ^ Ian Shirley. "KING CRIMSON - LARKS' TONGUES IN ASPIC". Record Collector. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony; Henke, James; George-Warren, Holly (1992). The Rolling Stone Album Guide. Random House. ISBN 0-679-73729-4.

- ^ Niester, Alan (30 August 1973). "King Crimson: Larks' Tongues in Aspic : Music Reviews". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2019.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^ Martin 1998, p. 225.

- ^ Q Classic: Pink Floyd & The Story of Prog Rock, 2005.

- ^ Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (7 February 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

- ^ "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, by MURMUR". Season of Mist. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ "Interview with DAVID CROSS". Dmme.net.

- ^ "Billboard entry". Billboard. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

Sources[]

- Hoffmann, Frank (2004). Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94950-1.

Further reading[]

- Karl, Gregory (2013). "King Crimson's Larks' Tongues in Aspic: A Case of Convergent Evolution". In Holm-Hudson, Kevin (ed.). Progressive Rock Reconsidered. Routledge. pp. 121–142. ISBN 978-1-135-71022-4.

- Martin, Bill (1998). Listening to the Future: The Time of Progressive Rock, 1968-1978. Open Court Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8126-9368-3.

External links[]

- Larks' Tongues in Aspic at Discogs (list of releases)

- 1973 albums

- King Crimson albums

- Albums produced by Robert Fripp

- Island Records albums

- Polydor Records albums

- E.G. Records albums

- Virgin Records albums

- Atlantic Records albums