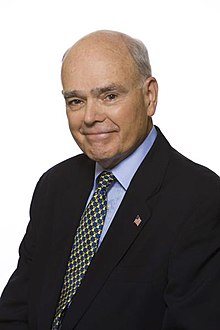

Lee Edwards

Lee Edwards | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Historian and author Heritage Foundation fellow |

Lee Edwards (born 1932) is a conservative academic and author, currently a fellow at The Heritage Foundation. He is a historian of the conservative movement in America.[1][2]

Background[]

Edwards was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1932. Edwards says he was influenced by the politics of his parents, both anti-communist. His father was a journalist for the Chicago Tribune.[3]

He holds a bachelor's degree in English from Duke University and a doctorate in political science from Catholic University.[4]

Career[]

Edwards helped found Young Americans for Freedom (YAF) in 1960, and then worked for the YAF magazine New Guard as editor.[5] In 1963, he became news director of the Draft Goldwater Committee.[5]

Edwards has written biographies of Ronald Reagan, William F. Buckley, Edwin Meese III and Goldwater,[6][7][8][9] as well as a number of other books, which include The Conservative Revolution: The Movement That Remade America[10] and The Power of Ideas.[11]

Edwards has been a senior editor for the World & I, owned by a subsidiary of Sun Myung Moon's Unification Church.[12][13]

Edwards was the founding director of the Institute on Political Journalism at Georgetown University and a fellow at the Harvard Institute of Politics.[14] He is a past president of the Philadelphia Society and has been a media fellow at the Hoover Institution.[15][16][17]

He is a distinguished fellow in conservative thought at the B. Kenneth Simon Center for American Studies at The Heritage Foundation,[18] and as of 2011, holds the title of adjunct professor of politics at the Catholic University of America and at the Institute of World Politics.[19]

Edwards is chairman of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation[20] and a signatory of the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism.[21]

Personal[]

He and his wife, Anne, who assists him in all his writing, live in Alexandria, Virginia. They have two daughters and eleven grandchildren.

References[]

- ^ Hoplin, Nicole; Robinson, Ron (2008). Funding fathers: the unsung heroes of the conservative movement. Regnery Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-59698-562-9.

- ^ Regnery, Alfred S. (2008). Upstream: the ascendance of American conservatism. Regnery Publishing. p. x. ISBN 978-1-4165-2288-1.

- ^ Spalding, Elizabeth (16 September 2010). "Edwards, Lee". First Principles. Intercollegiate Studies Institute. Retrieved 9 June 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "Dr. Lee Edwards". omeka.binghamton.edu. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Olmstead, Gracy. "Lee Edwards: When the 'New Right' Was New". The American Conservative. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Edwards, Lee (27 January 2011). "Reagan prepared for the presidency in the political wilderness". The Washington Examiner. Retrieved 9 June 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Judis, John B. (24 September 1995). "The Man Who Knew Too Little". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Lopez, Kathryn Jean (12 May 2010). "Lee Edwards on His WFB Biography". National Review. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Edwards, Lee (2008). "Goldwater, Barry (1909–1998)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 211–12. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n127. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ^ Piper, Randy (17 March 2005). "Gingrich VisionS – Winning The Future". US Progressive Conservatives. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Weisberg, Jacob (9 January 1998). "Happy Birthday, Heritage Foundation". Slate. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Annys Shin (3 May 2004). "News World Layoffs to Idle 86 Workers". Washington Post. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Good-bye to Isolationism". The World &nd I. June 1995. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ "Former Fellow Lee Edwards". Harvard University Institute of Politics. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ "2009 National Presentations". Philadelphia Society. Retrieved 9 June 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20100223102538/http://phillysoc.org/presiden.htm. Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "William and Barbara Edwards Media Fellows by year". Hoover Institution. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ "Lee Edwards, Ph.D." The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ "Lee Edwards". The Institute of World Politics. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20090626064941/http://www.globalmuseumoncommunism.org/content/board-directors. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism - Press Release". Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. 9 June 2008. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

External links[]

- The Lee Edwards papers at the Hoover Institution Archives.

- Interview with Lee Edwards by Stephen McKiernan, Binghamton University Libraries Center for the Study of the 1960s

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1932 births

- Living people

- Catholic University of America alumni

- Catholic University of America School of Arts and Sciences faculty

- Duke University Trinity College of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Georgetown University faculty

- The Heritage Foundation

- Illinois Republicans

- Harvard Kennedy School staff

- University of Paris alumni

- Virginia Republicans

- People from Alexandria, Virginia

- American expatriates in France